Strategies to Facilitate Interorganizational Collaboration in County-Level Opioid Overdose Prevention and Response: A Qualitative Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

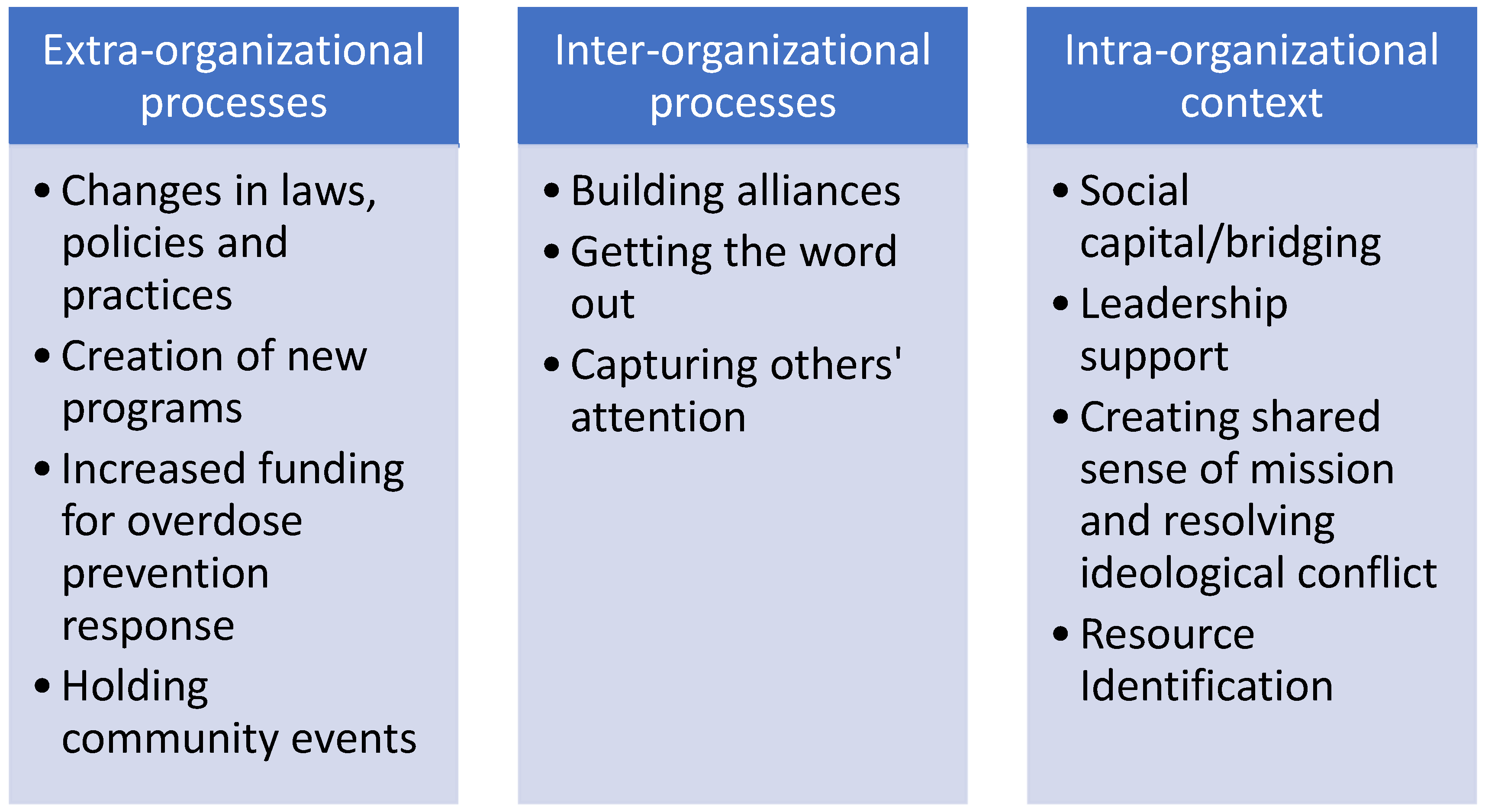

3. Results

3.1. Differences Between Counties in Macro-Level Factors: The Extra-Organizational Landscape

I think we have faced a lot of difficulty with like city image, because people have expressed concern about like, if we put out Narcan, they think it’s going to increase people using or misusing medications or drugs… So, it’s a little bit of a battle in some ways. I wouldn’t say it’s all been positive, it’s just a little bit more difficult. Like people don’t outright say anything, but they also are not super gung-ho about it either….(County A Participant 20, White male)

I think there’s some differing ideas as to what is best for our community or what our community would be receptive to. We’ve actually found that as well with our community Narcan training. We didn’t have as big of a turnout as we were hoping and some of the agencies involved with that training thought we should just cancel it… It was thrown around the idea of just doing a commercial Narcan training or posting a video on Facebook of how to use Narcan and—instead of kind of challenging the community and making them realize and accept that overdose is not—doesn’t discriminate against certain communities. It affects everyone. So, it’s just kind of working through that.(County A, Participant 6, White female)

When we first arrived, all of our more harm reduction overdose prevention efforts were met with a lot of resistance from the community, from first responders, even the fire department. We really quickly partnered with the [County A Fire Department] on the [overdose response] project… Which then, kind of once you have a partner in the first responder world that’s kind of subscribed to what you’re doing, then the other ones tend to [accept it], cause they talk, right? They’re all friends, they’re peers.(County B, Participant 18, White male)

So, the task force was in existence pre-COVID, right? So, it grew out of a concern within [County B’s] Health and Human Services around opiate and heroin issues and just trying to bring community members and the county government and all the partners together to try to effectively address the opiate and heroin issue. COVID caused a pause in it all. And so, it got restarted probably about a year, a year and a half ago now. And then kind of morphed our work and took a different strategy or a different approach than what the task force was doing before COVID… Our organization was the fiscal agent for the Drug Free Communities grant, so focused a lot on youth prevention and coalition building and those kinds of things… So, in rebooting the task force several of the people that were on the… design committee I had worked with… approached me personally about potentially becoming a leader for the task force in the new revised, updated [name of coalition].(County B, Participant 8, White female)

3.2. Forming Alliances: Diverse Group of Stakeholders to Address Multiple Needs of People with OUD

Participant: It is difficult to get all the people in the same room, because a lot of these people do have very busy schedules… We try to add people from like all different aspects of [name of city]. So, we have, like pharmacists. We have people from the mobile integrated health unit. We have a police lieutenant that helps like pick our cases. We have uh someone from the medical examiner’s office that talks about the autopsy report. In the toxicology findings we have a social worker from the medical examiner’s office. We review the cases in advance, and if they have any child involvement or any minors at all that could be in the school district we include the lead school social worker for [name of city] schools… anyone who has potentially had like been in touch or worked with the decedents in the cases.(County A, Participant 20, White male)

I think our taskforce, one of the things that we’ve done in the last year or year and a half, we’re spending quite a bit of time educating together, learning together, and building understanding about resources, as well as data… And we have all the sectors there. We have law enforcement, and we have healthcare, and we have therapists, and things like that. So, I think understanding where everybody starts and stops, and even questioning and pushing why can’t we do something a certain way.(County B, Participant 4, White female)

So, I think the Health and Human Services is very committed and they want to see success and so they have a very strong role in it, and they have access to resources and things that nobody else does, right, because they’re the county. I think they are really trying hard to figure out how do we engage their community partners. But I think there’s some power differential there like an organization like mine… I’m at the table, but I’m the only really, community partner at the design table… And so, having them at the table and having their ear, you can really potentially make things happen… The negative is that sometimes they are overpowering, and they forget that they’re not the sole solutions to the problems, right, and sometimes it’s hard to knock on the door and say, “Hello, we’d like to come in.”(County B, Participant 8, White female)

You also are seeing just both within the meetings and then outside of the meetings, the level of connection that’s happening between agencies and sometimes between individuals that may not have even had the opportunity to know the function of the other person or the other agency prior to some of this collaborative work and that can be really powerful. So, … we had the folks from the housing division come in and present in response to what we were seeing with one particular overdose incident, and their perspective, and then being able to connect them into this process. And knowing a little bit more about what they were seeing on their end really enhances our ability to all work together.(County A, Participant 21, White female)

What’s I guess, what’s made it easier to basically having the conversations, you know, they don’t know what they don’t know. So, if a city doesn’t know you offer a service, or that you can provide a service, then they’ll never get on board. So obviously being part of OFRs… and all that is good, because you see who is in those meetings.(County A, Participant 1, Black male)

Some barriers are that there’s a lot of people working in substance use prevention kind of independently. And so a barrier is getting people on the same track, not duplicating services, making sure we’re all moving in a direction together. We have definitely had that lesson in making sure that we’re not competing with each other for the same audience, trying to accomplish the same program.(County B, Participant 7, White female)

3.3. Creating a Shared Mission Helps Organizations to Collaborate

Interviewer: And how does your organization communicate with other organizations that are involved in overdose prevention?

Well, we hear from the participants or from… our community-based organization meetings provided by DHS, or from warm handoffs from somebody we may know through our networks. And we then discuss, these are important items to us. This is our mission for harm reduction, and we find a mutual understanding with these organizations, with their goals and what they anticipate with their programming, and we match it and if it’s parallel, we get together and we tackle those things together. And if they’re not parallel, what can we do to find some commonality to meet your mission and your goals regarding harm reduction and meet ours as well. Again, reminding you that silos is the death of prevention and the death of harm reduction.(County A, Participant 9, Hispanic male)

Interviewer: Are there any barriers to those collaborations?

Yeah. Yes. So, police primarily. Which is understandable. Super frustrating, but they come at it from a law enforcement perspective, ‘cause it’s their job. And so, helping people to reduce the harm associated with their use, to them, can sometimes sound like allowing them to break the law, and being okay with them breaking the law… So, they’re much slower, I think, to come around and do… certainly resist with partnering with us on paper… And then, we have conversations with our partners, with first responder partners about the language that they use. It’s baked into the culture sometimes, that you use words like “Junky” or “Addict” or any of that kind of stuff that’s stigmatizing. And people don’t realize it’s stigmatizing until it’s been pointed out. And even then, there’s a little bit of resistance.(County B, Participant 18, White male)

We are actively working and supporting one another’s efforts. For example, we go out every Monday. We had a meeting about a month ago in regards to what targeted areas do we need to go to, and we invited everyone to our end of the year celebration… And just because of the relationships that we have built this past year, everyone came out to support us there.(County A, Participant 27, Black female)

Just getting together regularly seems to help. I mean, we see each other now, at different events, there was an overdose prevention thing in the [name of park] that people had tables, and it was all the same groups. So it was, you know, good to see each other again… I mean building friendships really, among the people in those groups is really kind of what solidifies things.(County A, Participant 18, White male)

There’s a big need. There’s all these gaps in services, right? They exist everywhere. But especially between what would be seen as competing organizations, they’re all competing for the same clients, or whatever… There’s no lack of participants, right? And so, hopefully with the coalition, we’re trying to get everybody at the same table, and speaking the same language, and helping each other with the efforts… Having all these different partners kind of work together and pool resources is gonna be really, really helpful.(County B, Participant 18, White male)

3.4. Problem-Focused Discussions

If we think there could’ve been a program that might have been able to intervene with this individual or prevent the overdose deaths, oftentimes an agency can say “Oh, we have that,” or “We have—we know someone who does that and can connect you” and it’s just that kind of setting brings—brings up a lot of resource sharing for agencies who are on those meetings…(County A, Participant 6, White female)

As far as OFRs, it’s definitely helped us collaborate with other organizations. We’ve been working on getting some of those BAAs [business association agreements] in place. So, looking at the DOC. I think that’s how that one started was through a recommendation from an OFR which was great, and then looking at other mental health organizations… Those conversations have started because of OFRs, so again, you know, we break down those silos. We collaborate. We are finding out what works for folks. And then also it’s good to see what everyone else is doing. I think everyone has come from the standpoint of we have this north star of this, like mission of, preventing overdose, and I think that drives everyone’s passion and understanding.(County A, Participant 1, Black male)

3.5. Key People in Organizations Act as Bridges

So, we have this collaborative [person’s name omitted] from [OTP], she um is that hub. So, every flyer, every new bit of information, goes to [person’s name omitted], and she’s the one that distributes. How she became that person, I don’t know. But she’s really good at it, and she does that.(County A, Participant 4, White female)

Yeah. I think the gaps are coordination, for sure. Just coordination of systems and agencies and organizations because it’s incredibly challenging for people to get through a system to get what they need because you just have to go all over the place. Each time you go someplace, you got to retell your story, you got to be reassessed, got to be this and that. We always talk about trauma-informed and person-centered care, we have the least probably trauma-informed system and person-centered system… The navigator [in our program] really helps that person connect all those pieces so they’re not in it by themselves. And if you walk with that person through this journey, they’re gonna be more successful than just pointing them in the right direction saying, “Go here.” You know?(County A, Participant 16, White male)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Vital Statistics System: Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- National Institutes of Health. Drug Overdose Deaths: Facts and Figures; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wisconsin Department of Health Services. WISH: Opioid overdose deaths, Wisconsin 2000–2023; Wisconsin Department of Health Services: Madison, WI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mattson, C.L.; Tanz, L.J.; Quinn, K.; Kariisa, M.; Patel, P.; Davis, N.L. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths--United States, 2013–2019. MMWR 2021, 70, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereish, E.H.; Bradford, J.B. Intersecting Identities and Substance Use Problems: Sexual Orientation, Gender, Race, and Lifetime Substance Use Problems. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2014, 75, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.M.; Shieu-Yee, K.; Chen, S.; DePuccio, M.J.; Jackson, R.D.; McAlearney, A.S. Community coalitions’ perspectives on engaging with hospitals in Ohio to address the opioid crisis. Popul. Health Manag. 2022, 25, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Onofrio, G.; Chawarski, M.C.; O’Connor, P.G.; Pantalon, M.V.; Busch, S.H.; Owens, P.H.; Hawk, K.; Bernstein, S.L.; Fiellin, D.A. Emergency Department-Initiated Buprenorphine for Opioid Dependence with Continuation in Primary Care: Outcomes During and After Intervention. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakeman, S.E.; Larochelle, M.R.; Ameli, O.; Chaisson, C.; McPheeters, J.T.; Crown, W.H.; Azocar, F.; Sanghavi, D.M. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e1920622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakeman, S.E.; Rigotti, N.A.; Chang, Y.; Herman, G.E.; Erwin, A.; Regan, S.; Metlay, J.P. Effect of integrating substance use disorder treatment into primary care on inpatient and emergency department utilization. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampman, K.; Jarvis, M. American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) national practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. J. Addict. Med. 2015, 9, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.R.; Johnson, K.A.; Thomas, C.P.; Reif, S.; Socías, M.E.; Henry, B.F.; Neighbors, C.; Gordon, A.J.; Horgan, C.; Nosyk, B.; et al. Opioid use disorder Cascade of care framework design: A roadmap. Subst. Abus. 2022, 43, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munetz, M.R.; Griffin, P.A. Use of the sequential intercept model as an approach to decriminalization of people with serious mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2006, 57, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.; Harrington, C.; Evans, E.A. A scoping review of community-based post-opioid overdose intervention programs: Implications of program structure and outcomes. Health Justice 2023, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, S.M.; Schoenberger, S.F.; Waye, K.M.; Walley, A.Y. A scoping review of post opioid-overdose interventions. Prev. Med. 2019, 128, 105813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overdose Fatalaity Review. 2024. Available online: https://www.mcw.edu/-/media/MCW/Departments/Epidemiology/OFR/Overdose-Fatality-Reviews-Companion-Document-November-2024.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- The HEALing Communities Study Consortium. The HEALing (Helping to End Addiction Long-term) Communities Study: Protocol for a cluster-randomized trial at the community level to reduce opioid overdose deaths through implementation of an integrated set of evidence-based practices. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020, 217, 108335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, D.K.; Belenko, S.; Dennis, M.L.; Wasserman, G.A.; Joe, G.W.; Aarons, G.A.; Bartkowski, J.P.; Becan, J.E.; Elkington, K.S.; Hogue, A.; et al. The comparative effectiveness of Core versus Core+Enhanced implementation strategies in a randomized controlled trial to improve substance use treatment receipt among justice-involved youth. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster-Fishman, P.; Salem, D.A.; Allen, N.A.; Fahrbach, K. Facilitating interorganizational collaboration: The contributions of interorganizational alliances. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2001, 29, 875–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohnett, E.; Vacca, R.; Hu, Y.; Hulse, D.; Varda, D. Resilience and fragmentation in healthcare coalitions: The link between resource contributions and centrality in health-related interorganizaitonal networks. Soc. Netw. 2022, 7, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeren, T.; Ward, C.; Sewell, D.; Ashida, S. Applying network analysis to assess the development and sustainability of multi-sector coalitions. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerrissey, M.; Singer, S.J. Factors affecting collaborations between clinical and community service organizations. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2023, 48, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, S.J.C.; Alma, M.A.; Bak, M.; van der Krieker, L.; Bruggeman, R. Values and practice of collaboration in a mental health care system in the Netherlands: A qualitative study. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2023, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.; Segura, C.; Niño, N. Implementing COVID-19 surveillance through inter-organizational coordination: A qualitative study of three cities in Colombia. Health Policy Plan. 2022, 37, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, C.; Han, H.; Kim, D.H.; Coderre-Ball, A.M.; Alam, N. Family physicians collaborating for health system integration: A scoping review. Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showalter, D.; Wenger, L.D.; Lambdin, B.H.; Wheeler, E.; Binswanger, I.A.; Kral, A.H. Bridging institutional logics: Implementing naloxone distribution for people existing jail in three California counties. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 285, 114293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, R.; Willging, C.; Hurlburt, M.; Fenwick, K.; Aarons, G. Contracting as a bridging factor linking outer and inner contexts during EBP implementation and sustainment: A prospective study across muliple U.S. public service systems. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster-Fishman, P.; Berkowitz, S.L.; Lounsbury, D.W.; Jacobson, S.; Allen, N.A. Building collaboratie capacity in community coalitions: A review and integrative framework. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2001, 29, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, R.; Westra, D.; van Raak, A.J.A.; Ruwaard, D. So happy together: A review of the literature on the determinants of effectiveness of purpose-oriented networks in healthcare. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2023, 80, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swann, W.L.; Dinardi, M.; Schreiber, T.L. Association Between Interorganizational Collaboration in Opioid Response and Treatment Capacity for Opioid Use Disorder in Counties of Five States: A Cross-Sectional Study. Subst. Abus. Res. Treat. 2022, 16, 117822182211119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, S.; Van Belle, S.; Maioni, A. Learning from intersectoral action beyond health: A meta-narrative review. Health Policy Plan. 2021, 36, 552–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustin, R.; Nichols, J.; Martin, P. Individualizing Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) treatment: Time to fully embrace a chronic disease model. J. Reward Defic. Syndr. 2015, 1, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, N.A.; Zimmerman, M.A. Beyond the individual: Toward a nomological network of organizational empowerment. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2004, 34, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarons, G.; Fettes, D.; Hurlburt, M.; Palinkas, L.; Gunderson, L.; Willging, C.; Chaffin, M. Collaboration, negotiation, and coalescense for interagency-collaborative teams to scale-up evidence-based practice. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2014, 43, 915–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, Z.P. A network perspective on the processes of empowered organizations. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2014, 53, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plested, B.; Jumper-Thurman, P.; Edwards, R.W. Community readiness: A tool for effective community-based prevention. Prev. Res. 1989, 5, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A.; Knudsen, H.K.; Walker, D.M.; Chassler, D.; Lunze, K.; Westgate, P.M.; Oga, E.; Rodriguez, S.; Tan, S.; Holloway, J.; et al. Effects of the Communities that Heal (CTH) intervention on perceived opioid-related community stigma in the HEALing Communities Study: Results of a multi-site, community-level, cluster-randomized trial. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2024, 32, 100710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavel, J.J.V.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N.; et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, B. Profiling capacity for coordination and systems change: The relative contribution of stakeholder relationships in interorganizational collaboratives. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2009, 44, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, E.N.; Baker, R.; Hartung, D.M.; Hildebran, C.J.; Nguyen, T.; Collins, D.M.; Larsen, J.E.; Stack, E. Reducing overdose after release from incarceration (ROAR): Study protocol for an intervention to reduce risk of fatal and non-fatal opioid overdose among women after release from prison. Health Justice 2020, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.P.; Staton, M.D.; Gastala, N. Identifying unique barriers to implementing rural emergency department-based peer services for opioid use disorder through qualitative comparison with urban sites. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2022, 17, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, E.A.; Baird, J.; Yang, E.S.; Mello, M.J. Adoption and Utilization of an Emergency Department Naloxone Distribution and Peer Recovery Coach Consultation Program. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2019, 26, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardwell, G.; Kerr, T.; Boyd, J.; McNeil, R. Characterizing peer roles in an overdose crisis: Preferences for peer workers in overdose response programs in emergency shelters. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 190, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebling, E.J.; Perez, J.J.S.; Litterer, M.M.; Greene, C. Implementing hospital-based peer recovery support services for substance use disorder. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2021, 47, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, A.E.; Jeffers, A.; Allen, B.; Paone, D.; Kunins, H.V. Relay: A Peer-Delivered Emergency Department-Based Response to Nonfatal Opioid Overdose. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 1392–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogan, C.; Jennings, L.; Haynes, L.; Barth, K.; Moreland, A.; Oros, M.; Goldsby, S.; Lane, S.; Funcell, C.; Brady, K. Implementation of emergency department-initiated buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in a rural southern state. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2020, 112S, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waye, K.M.; Goyer, J.; Dettor, D.; Mahoney, L.; Samuels, E.A.; Yedinak, J.L.; Marshall, B.D.L. Implementing peer recovery services for overdose prevention in Rhode Island: An examination of two outreach-based approaches. Addict. Behav. 2019, 89, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formica, S.W.; Waye, K.M.; Benintendi, A.O.; Yan, S.; Bagley, S.M.; Beletsky, L.; Carroll, J.J.; Xuan, Z.; Rosenbloom, D.; Apsler, R.; et al. Characteristics of post-overdose public health-public safety outreach in Massachusetts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 219, 108499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, B.; Bailey, K.; Dunnigan, M.; Aalsma, M.; Bell, L.; O’Brien, M. Comparing practices used in overdose fatality review teams to recommended implementation guidelines. J. Public Health Manag. 2022, 28, S286–S294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | Race/Ethnicity | Median Income | Urbanicity | Overdose Rate 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County A | 961,205 | White 49% Black 26% Hispanic 16% | USD 62,000 | Urban | 58.2/100,000 |

| County B | 406,978 | White 87% Black 1.7% Hispanic 5.4% | USD 88,985 | Suburban/rural | 14.8/100,000 |

| County A | County B | |

|---|---|---|

| Academia ** | 2 | 0 |

| Criminal Justice | 2 | 2 |

| Department of Health | 4 | 2 |

| EMS | 4 | 1 |

| Government | 3 | 0 |

| Harm Reduction | 3 | 7 |

| Other Social Services | 1 | 2 |

| Peer Support Specialists | 3 | 2 |

| SUD Treatment | 6 | 4 |

| Total # of participants | 27 | 19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dickson-Gomez, J.; Krechel, S.; Ohlrich, J.; Hernandez-Meier, J.; Kostelac, C. Strategies to Facilitate Interorganizational Collaboration in County-Level Opioid Overdose Prevention and Response: A Qualitative Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1765. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121765

Dickson-Gomez J, Krechel S, Ohlrich J, Hernandez-Meier J, Kostelac C. Strategies to Facilitate Interorganizational Collaboration in County-Level Opioid Overdose Prevention and Response: A Qualitative Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1765. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121765

Chicago/Turabian StyleDickson-Gomez, Julia, Sarah Krechel, Jessica Ohlrich, Jennifer Hernandez-Meier, and Constance Kostelac. 2025. "Strategies to Facilitate Interorganizational Collaboration in County-Level Opioid Overdose Prevention and Response: A Qualitative Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1765. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121765

APA StyleDickson-Gomez, J., Krechel, S., Ohlrich, J., Hernandez-Meier, J., & Kostelac, C. (2025). Strategies to Facilitate Interorganizational Collaboration in County-Level Opioid Overdose Prevention and Response: A Qualitative Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1765. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121765