Digital Health Literacy of People with Intellectual Disabilities: A Scoping Review to Map the Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What specific challenges are mentioned for people with intellectual disabilities in relation to digital health literacy?

- What needs-oriented adaptations are proposed for digital health literacy concepts for people with intellectual disabilities?

2. Methods

2.1. Overall

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

- (1)

- Adults with intellectual disabilities in any living context, e.g., outpatient or inpatient care;

- (2)

- DHL is addressed;

- (3)

- Written in English or German;

- (4)

- All study designs, regardless of their design and quality, as well as grey literature, including dissertations and editorial articles;

- (5)

- Timespan from 2009 to 2023.

2.4. Study Selection

- Mentioned specific content of digital health information of people with intellectual disabilities;

- Included an application to improve access to health information or health management;

- Deepened the understanding of user experiences and identified support needs within social environments to access digital health information and transfer them into real life;

- Described learning approaches that mentioned digital health information;

- An assessment of risks and facilitators.

2.5. Data Charting

3. Results

3.1. General Results

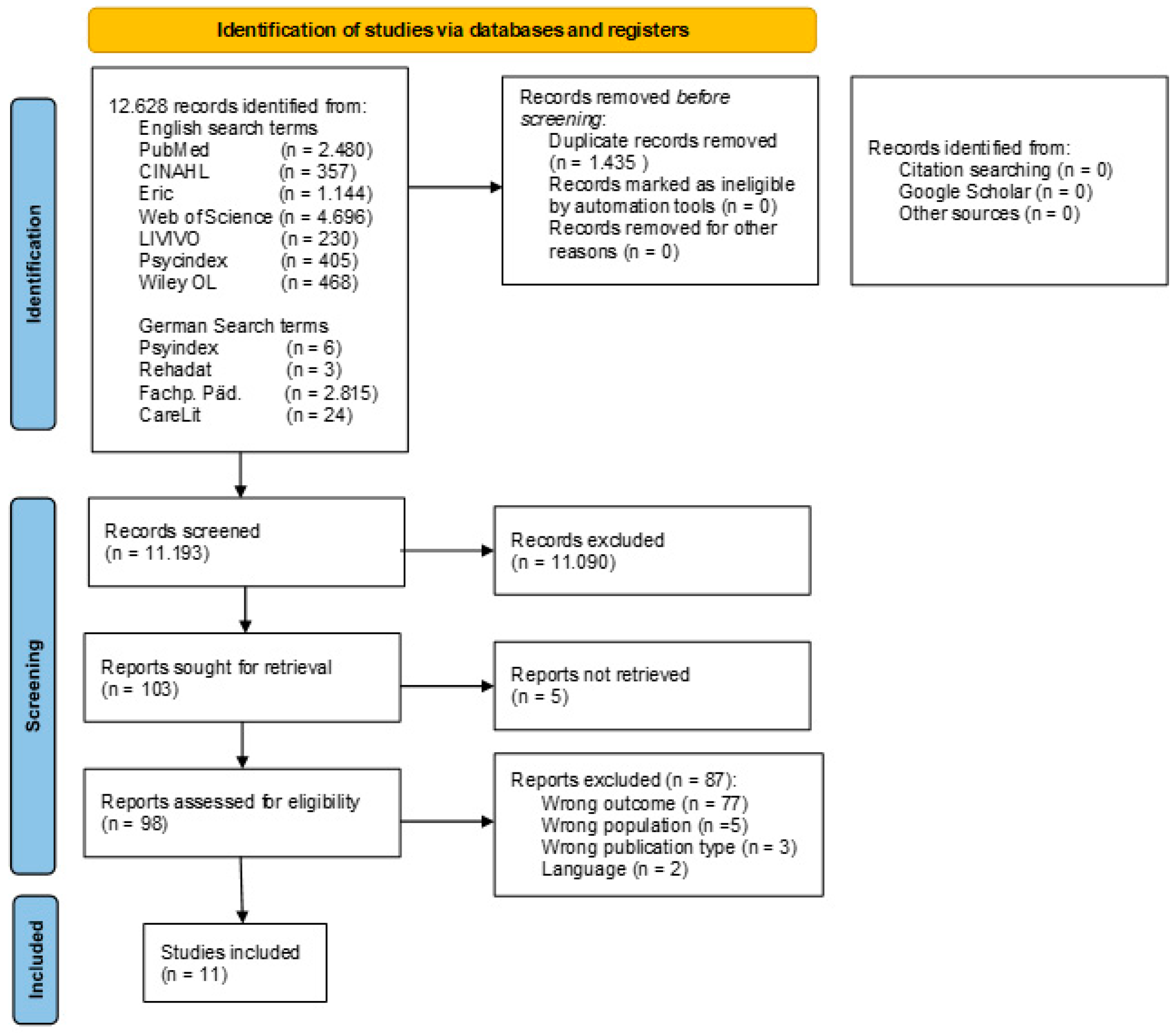

3.1.1. Literature Search

3.1.2. Study Characteristics

3.1.3. Quality Appraisal

3.2. Factors of Digital Health Literacy

3.2.1. Situational Factors

3.2.2. Personal Factors

3.2.3. Environmental Factors

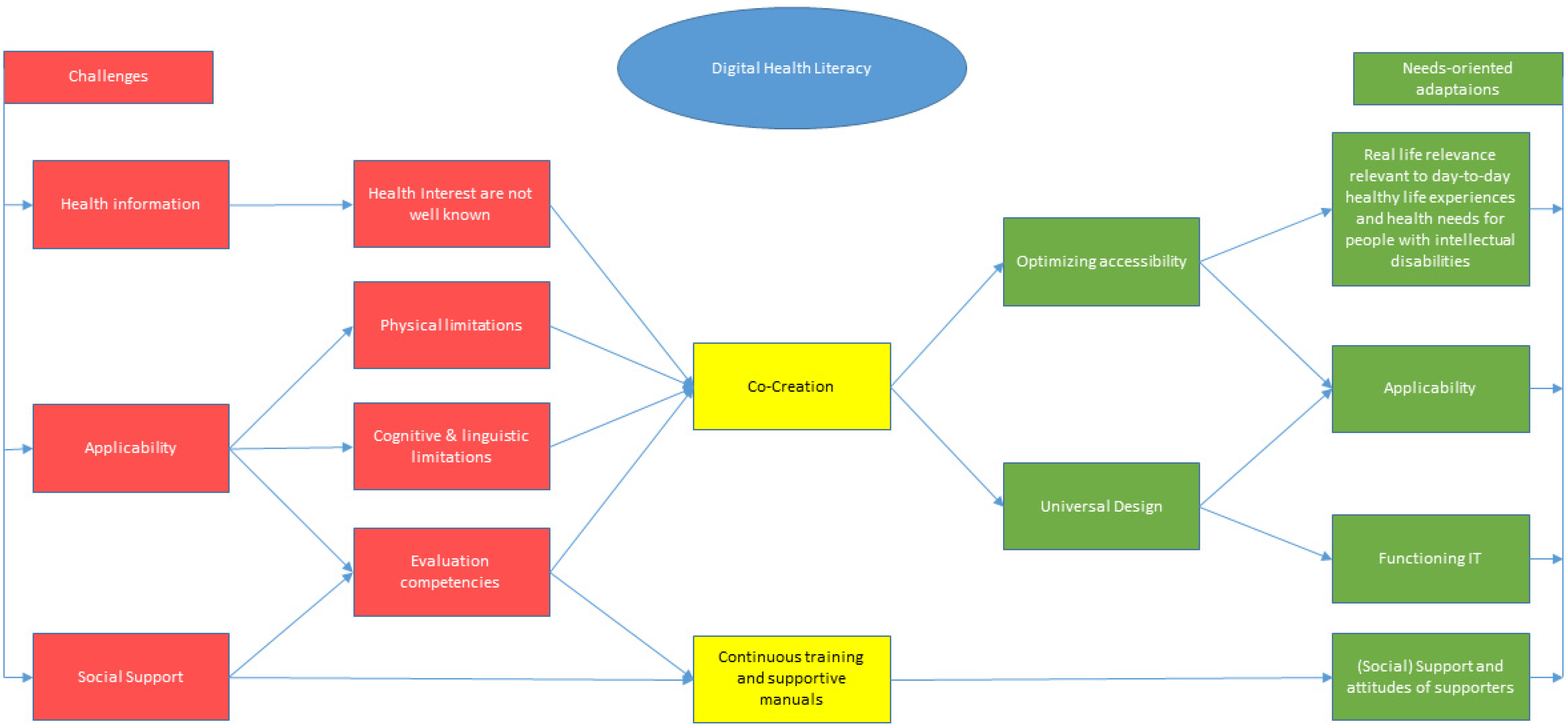

3.3. Challenges

3.3.1. Health Information

3.3.2. Applicability

3.3.3. Social Support

3.4. Needs-Oriented Adaptations

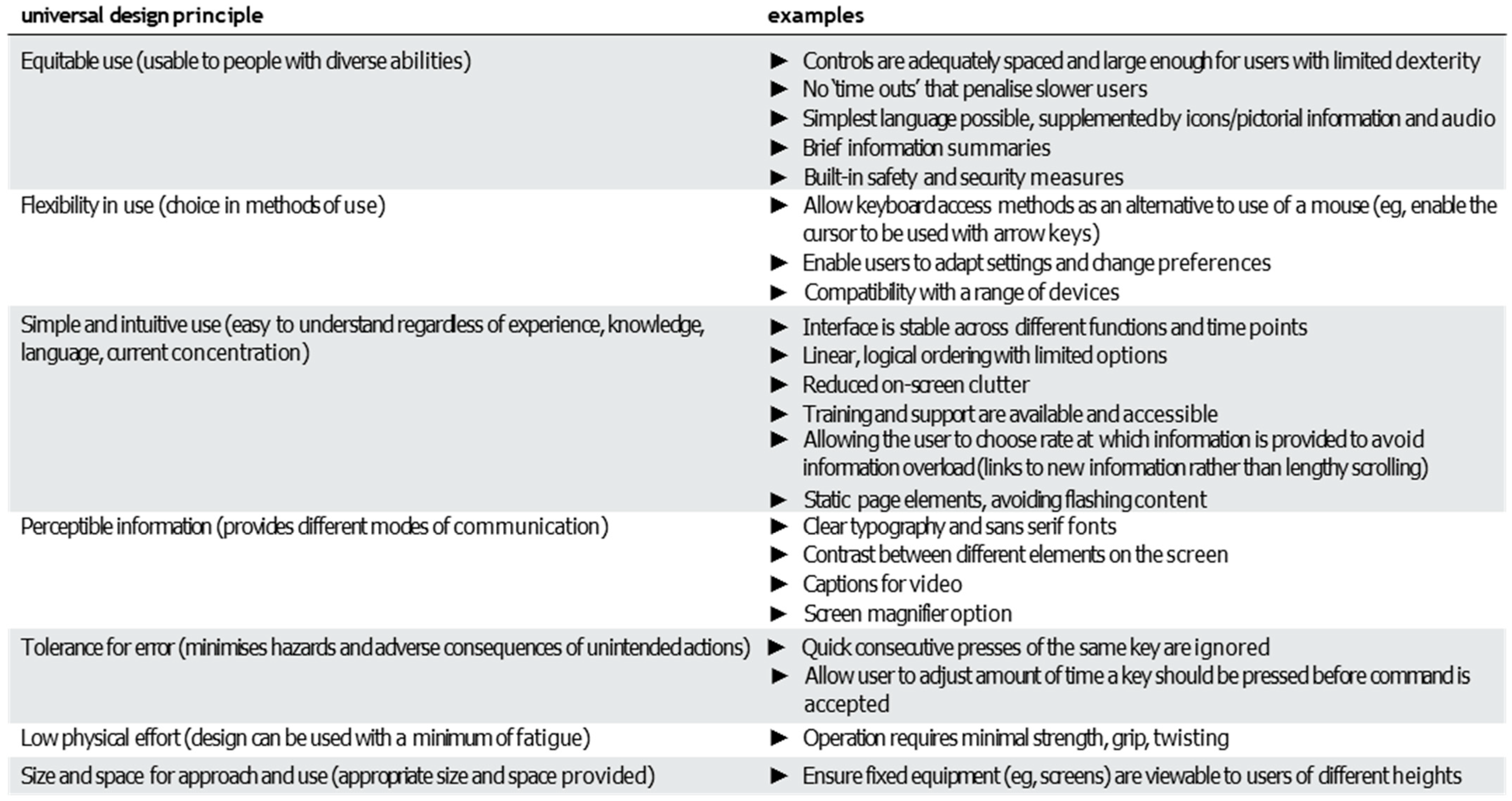

3.4.1. Applicability

3.4.2. Functional IT

3.4.3. Support

3.4.4. Training

3.4.5. Manuals

3.4.6. Real-Life Relevance

3.5. Summary

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Current Use for a Population-Specific Theoretical Framework

4.3. Digital Health Literacy Approach

4.4. Knowledge Gaps and Future Directions

4.5. Limitations

4.6. Implications and Benefits for Developing a Population-Specific Theoretical Framework of Digital Health Literacy

- A resource-oriented approach is central. The focus will be on people with intellectual disabilities and their health needs, and how validated digital health information and digital health applications can be applied to promote health management will be analyzed. Personal skills and social support will be considered.

- Real-life relevance has to be researched. This will be conducted utilizing a participatory approach and proxy surveys. For example, both people with intellectual disabilities and their support persons will be surveyed about relevant health topics and current use of digital technologies for health information and health management. Perspectives on benefits and risks, as well as motivation to use digital technologies for health, will also be surveyed.

- Our network of practitioners will be consulted to incorporate non-academic knowledge base. This will ensure that important sources of information and practical knowledge will be included.

- An initial framework will be developed based on the research results obtained. A holistic intervention approach will be taken to develop the framework. The focus will be on digital health strategies to address the learning needs of people with intellectual disabilities and their critical interaction with digital content. The discussion groups should involve different stakeholders, including people with intellectual disabilities and their support persons, as well as institution managers.

- The implementation of the framework in practice will be analyzed, and the framework will be modified accordingly.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DHL | Digital health literacy |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020–2025, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 9789240020924. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Digital Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/health-topics/digital-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Frielink, N.; Oudshoorn, C.E.M.; Embregts, P.J.C.M. eHealth in support for daily functioning of people with intellectual disability: Views of service users, relatives, and professionals on both its advantages and disadvantages and its facilitating and impeding factors. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 46, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dratva, J.; Schaeffer, D.; Zeeb, H. Digitale Gesundheitskompetenz der Bevölkerung in Deutschland: Aktueller Stand, Konzepte und Herausforderungen. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2024, 67, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynn, R.; Oyeyemi, S.O.; Budrionis, A.; Marco-Ruiz, L.; Yigzaw, K.Y.; Bellika, J.G. Electronic Health Use in a Representative Sample of 18,497 Respondents in Norway (The Seventh Tromsø Study—Part 1): Population-Based Questionnaire Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2020, 8, e13106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAIDD—American Association on Intellectual Disabilities and Developmental Disabilities. Defining Criteria for Intellectual Disability. Available online: https://www.aaidd.org/intellectual-disability/definition (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Nair, R.; Chen, M.; Dutt, A.S.; Hagopian, L.; Singh, A.; Du, M. Significant regional inequalities in the prevalence of intellectual disability and trends from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis of GBD 2019. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2022, 31, e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, L.; Cooper, S.-A.; Hughes-McCormack, L. Early death and causes of death of people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 31, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latteck, Ä.-D.; Bruland, D. Inclusion of People with Intellectual Disabilities in Health Literacy: Lessons Learned from Three Participative Projects for Future Initiatives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crondahl, K.; Eklund Karlsson, L. The Nexus Between Health Literacy and Empowerment. Sage Open 2016, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelikan, J.M.; Ganahl, K.; Roethlin, F. Health literacy as a determinant, mediator and/or moderator of health: Empirical models using the European Health Literacy Survey dataset. Glob. Health Promot. 2018, 25, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, M.; Wood, F.; Davies, M.; Edwards, A. The development of health literacy in patients with a long-term health condition: The health literacy pathway model. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinn, D. Critical health literacy health promotion and people with intellectual disabilities. Asia-Pac. J. Health Sport Phys. Educ. 2014, 5, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geukes, C.; Bruland, D.; Latteck, Ä.-D. Health literacy in people with intellectual disabilities: A mixed-method literature review. Kontakt 2018, 20, e416–e423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, N.S.; Voß, M.; Bruland, D.; Seidl, N.; Latteck, Ä.-D. Promoting health literacy in people with intellectual disabilities via explanatory videos: Scoping reviews. Health Promot. Int. 2023, 38, daab193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glencross, S.; Mason, J.; Katsikitis, M.; Greenwood, K.M. Internet Use by People with Intellectual Disability: Exploring Digital Inequality-A Systematic Review. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 24, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.; Shiels, O.; Fiori, S.; McCausland, D.; Bergström, H.; Koster, R.; Noorlandt, H.; Korfage, I.; Wallén, E.F. Bridging the digital divide for individuals with intellectual disabilities: Implications for well-being and inclusion. Brit. J. Learn. Disabil. 2025, 53, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiner, E.; Gómez-Puerta, M.; Cardona-Moltó, M.C. Internet use, risks and online behaviour: The view of internet users with intellectual disabilities and their caregivers. Brit. J. Learn. Disabil. 2017, 45, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kessel, R.; Wong, B.L.H.; Clemens, T.; Brand, H. Digital health literacy as a super determinant of health: More than simply the sum of its parts. Internet Interv. 2022, 27, 100500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, S.; Kim, Y.; Seomun, G. Digital health literacy: A concept analysis. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241287894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Arias López, M.P.; Ong, B.A.; Borrat Frigola, X.; Fernández, A.L.; Hicklent, R.S.; Obeles, A.J.T.; Rocimo, A.M.; Celi, L.A. Digital literacy as a new determinant of health: A scoping review. PLOS Digit. Health 2023, 2, e0000279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kessel, R.; Hrzic, R.; O’Nuallain, E.; Weir, E.; Wong, B.L.H.; Anderson, M.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Mossialos, E. Digital Health Paradox: International Policy Perspectives to Address Increased Health Inequalities for People Living with Disabilities. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e33819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin-Zamir, D.; Bertschi, I. Media Health Literacy, eHealth Literacy, and the Role of the Social Environment in Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruland, D.; Geffroy, D.; Latteck, Ä.-D. Digital Health Literacy of People with Intellectual Disabilities. A Scoping Review Protocol; Hochschule Bielefeld—University of Applied Sciences and Arts: Bielefeld, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr, P. Google Scholar: Warum eine (akademischen) Suchmaschine nicht ausreicht. Wissenschaftsmanagement 2009, 15, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Library Association. Digital Literacy. Available online: https://literacy.ala.org/digital-literacy/ (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- European Commission. DigComp 2.1: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens with Eight Proficiency Levels and Examples of Use; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2017; ISBN 978-92-79-68005-2. [Google Scholar]

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. Media Literacy. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/media-literacy (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Sørensen, K.; van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 9781849205931. [Google Scholar]

- Vetter, N.S.; Ilskens, K.; Seidl, N.; Latteck, Ä.-D.; Bruland, D. Health Literacy of People with Intellectual Disabilities: How Meaningful Is the Social Context for a Target Group-Oriented Model of Health Literacy? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruppu Arachchi, T.; Sitbon, L.; Zhang, J.; Koplick, S.; Hoogstrate, M.; Brereton, M. Web search to access health information by adults with intellectual disability. OIR 2023, 47, 1098–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, L.T.; Heidler, P.; King, I. Bridging the gap in healthcare: Creating an online health information prototype for individuals with intellectual disabilities to promote equity and knowledge transfer. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1194892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, M.N. Supporting Healthier Grocery-Shopping Habits for Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Using Self-Management and Technology: A Single-Case Pilot. Disabilities 2023, 3, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, V.; Conboy-Hill, S.; Taylor, D. Using virtual reality to provide health care information to people with intellectual disabilities: Acceptability, usability, and potential utility. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011, 13, e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watfern, C.; Heck, C.; Rule, C.; Baldwin, P.; Boydell, K.M. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Mental Health Website for Adults With an Intellectual Disability: Qualitative Evaluation. JMIR Ment. Health 2019, 6, e12958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmerón, L.; Gómez, M.; Fajardo, I. How students with intellectual disabilities evaluate recommendations from internet forums. Read Writ. 2016, 29, 1653–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, D.D.; Quinn, S.; Fullwood, C. Perceptions of the risks and benefits of Internet access and use by people with intellectual disabilities. Brit. J. Learn. Disabil. 2017, 45, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, R.; Hassiotis, A. Digital mental health and intellectual disabilities: State of the evidence and future directions. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2017, 20, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arachchi, T.K.; Sitbon, L.; Zhang, J. Enhancing Access to eLearning for People with Intellectual Disability: Integrating Usability with Learning. In Human-Computer Interaction—INTERACT 2017; Bernhaupt, R., Dalvi, G., Joshi, A.K., Balkrishan, D., O’Neill, J., Winckler, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 13–32. ISBN 978-3-319-67683-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufunaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Systematic Reviews of Aetiology and Risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI: London, UK, 2024; ISBN 9780648848820. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, T.H.; Habibi, N.; Aromataris, E.; Stone, J.C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Sears, K.; Hasanoff, S.; Klugar, M.; Tufanaru, C.; Moola, S.; et al. The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for quasi-experimental studies. JBI Evid. Synth. 2024, 22, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Quresi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Madalı-Kafes, B.; Alkan, Ş.B.; Kara, S.; Torun, B.; Kara, H.H. Health literacy and eHealth literacy in caregivers of students with special education needs: A cross-sectional survey study. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2025, 13, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeap, Z.; Keeley, J.; Skoss, R.; Hunt, S.; Kickett, A.; Saldaris, J.; Nevill, T.; Downs, J. Online health literacy resources for people with intellectual disability: Protocol for a grey literature scoping review. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e088509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Calis, J.F.E.; Bevelander, K.E.; van der Cruijsen, A.W.C.; Leusink, G.L.; Naaldenberg, J. Toward Inclusive Approaches in the Design, Development, and Implementation of eHealth in the Intellectual Disability Sector: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e45819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, A.; Jenaro, C.; Flores, N.; Bagnato, M.J.; Pérez, M.C.; Cruz, M. E-Health Interventions for Adult and Aging Population with Intellectual Disability: A Review. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paige, S.R.; Stellefson, M.; Krieger, J.L.; Anderson-Lewis, C.; Cheong, J.; Stopka, C. Proposing a Transactional Model of eHealth Literacy: Concept Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e10175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shogren, K.A.; Raley, S.K. Self-Determination and Causal Agency Theory: Integrating Research into Practice, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 9783031042607. [Google Scholar]

- Lussier-Desrochers, D.; Normand, C.L.; Romero-Torres, A.; Lachapelle, Y.; Godin-Tremblay, V.; Dupont, M.-È.; Roux, J.; Pépin-Beauchesne, L.; Bilodeau, P. Bridging the digital divide for people with intellectual disability. Cyberpsychology J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, J. Literacy und Geistige Behinderung; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Burack, J.A.; Evans, D.W.; Russo, N.; Napoleon, J.-S.; Goldman, K.J.; Iarocci, G. Developmental Perspectives on the Study of Persons with Intellectual Disability. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 17, 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Literacy | Definition/Description |

|---|---|

| Digital literacy | Digital literacy is “the ability to use information and communication technologies to find, evaluate, create, and communicate information, requiring both cognitive and technical skills” [29]. The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp 2.1) contains five competency areas: (a) information and data literacy, (b) communication and collaboration, (c) digital content creation, (d) safety, and (e) problem solving [30]. |

| Media literacy | Media literacy focuses on “use of critical thinking to parse or create mass media, especially as a consumer in an age of online misinformation and disinformation. … just as the latter refers to an ability to read, write, and understand words and phrases, the former refers to an ability to analyze, evaluate, and produce various kinds of media.” [31] |

| Health literacy | Health literacy is defined as the ability to obtain, read, understand, and use healthcare information to make appropriate/informed health decisions [32]. |

| eHealth literacy and media health literacy | During the search, the terms eHealth literacy and digital health literacy were used interchangeably. We agree that digital health literacy is an expansion of eHealth literacy. eHealth literacy, as well as media health literacy—combining media literacy and health literacy—is seen as a key attribute of digital health literacy [20]. This decision has no effect on the results because both terms were used in the search strategy. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bruland, D.; Geffroy, D.; Latteck, Ä.-D. Digital Health Literacy of People with Intellectual Disabilities: A Scoping Review to Map the Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111748

Bruland D, Geffroy D, Latteck Ä-D. Digital Health Literacy of People with Intellectual Disabilities: A Scoping Review to Map the Evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111748

Chicago/Turabian StyleBruland, Dirk, Daniel Geffroy, and Änne-Dörte Latteck. 2025. "Digital Health Literacy of People with Intellectual Disabilities: A Scoping Review to Map the Evidence" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111748

APA StyleBruland, D., Geffroy, D., & Latteck, Ä.-D. (2025). Digital Health Literacy of People with Intellectual Disabilities: A Scoping Review to Map the Evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111748