Transition from 24-Hour Shifts to Safer Work Schedules for Nurses in Latvian Healthcare: Policy Analysis and Recommendations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Policy Analysis Framework and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

- National legislation and policy documents, such as the Informative Report of the Ministry of Health on Flexible Work Planning Principles, the Cabinet of Ministers’ Orders and Regulations, and the national Health Workforce Strategy [1].

- National datasets and institutional reports, including the Riga Stradiņš University Workforce Study (2023) [11], data from the Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (SPKC, 2022) [37], and the State Labour Inspectorate’s 2024 report [38]. These were selected based on completeness, transparency, and relevance to healthcare workforce planning.

3.2. Analytical Process

- Contextual Mapping: The first stage identified and reviewed the existing Latvian regulatory and institutional framework governing nurses’ work schedules, highlighting areas of inconsistency with EU and WHO standards.

- Document Review: A systematic review of national and international policy documents, legal frameworks, and academic literature was conducted using targeted keyword searches (“nurse shift system”, “24-h shifts”, “health workforce reform”, “safe staffing”) across PubMed, WHO, and OECD databases. Two independent reviewers conducted relevance screening and cross-validation to minimise selection bias.

- Comparative Policy Mapping: Synthesis of international experience focusing on countries that have legislatively limited or prohibited 24 h shifts (e.g., Sweden, Norway, Germany, Australia). The analysis compared policy approaches, implementation strategies, and reported outcomes.

- Synthesis and Feasibility Assessment: Integration of findings to identify enablers, barriers, and preconditions for reform in Latvia, including pilot project feasibility and expected health, safety, and economic effects.

3.3. Analytical Framework

- Context: Legislative, socio-economic, and workforce conditions in Latvia;

- Content: Policy alternatives and international models for shift regulation;

- Process: Mechanisms of policy development, stakeholder involvement, and pilot implementation;

- Actors: Key institutions responsible for reform (Ministry of Health, hospitals, nursing associations).

4. Results

4.1. Latvia: Current Situation & Compliance

4.2. Employee Well-Being & Performance

4.3. Patient Safety Indicators

4.4. International Policies and Models

5. Discussion

5.1. Possible Alternative Shift Models in Latvia

- 1.

- 12 h shift model (day/night/rest)

- 2.

- Maximum shift duration—16 h or less

- 3.

- Modular work (2 × 6 h or 3 × 8 h shifts per day)

- 6 h shifts: 07:00–13:00, 13:00–19:00, 19:00–01:00, 01:00–07:00;

- 8 h shifts: 07:00–15:00, 15:00–23:00, 23:00–07:00.

- 4.

- Flexible shifts according to the unit profile

5.2. Implementation Prerequisites & Feasibility

Implementation Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

- Staff shortages and workload pressure: Latvia’s healthcare system faces a chronic shortage of nurses, making it difficult to ensure adequate staffing during shorter shifts. Mitigation: Phased introduction of 12 h or 8 h models with pilot projects and flexible staffing pools.

- Financial implications: Adjusting shift schedules may temporarily increase costs due to overtime compensation and recruitment needs. Mitigation: Align reform with EU funding streams and workforce development programs (2025–2029 strategy).

- Cultural and organizational resistance: Long-standing traditions of 24 h shifts create psychological and managerial inertia. Mitigation: Education of nurse managers, clear communication of safety benefits, and inclusion of staff in schedule design.

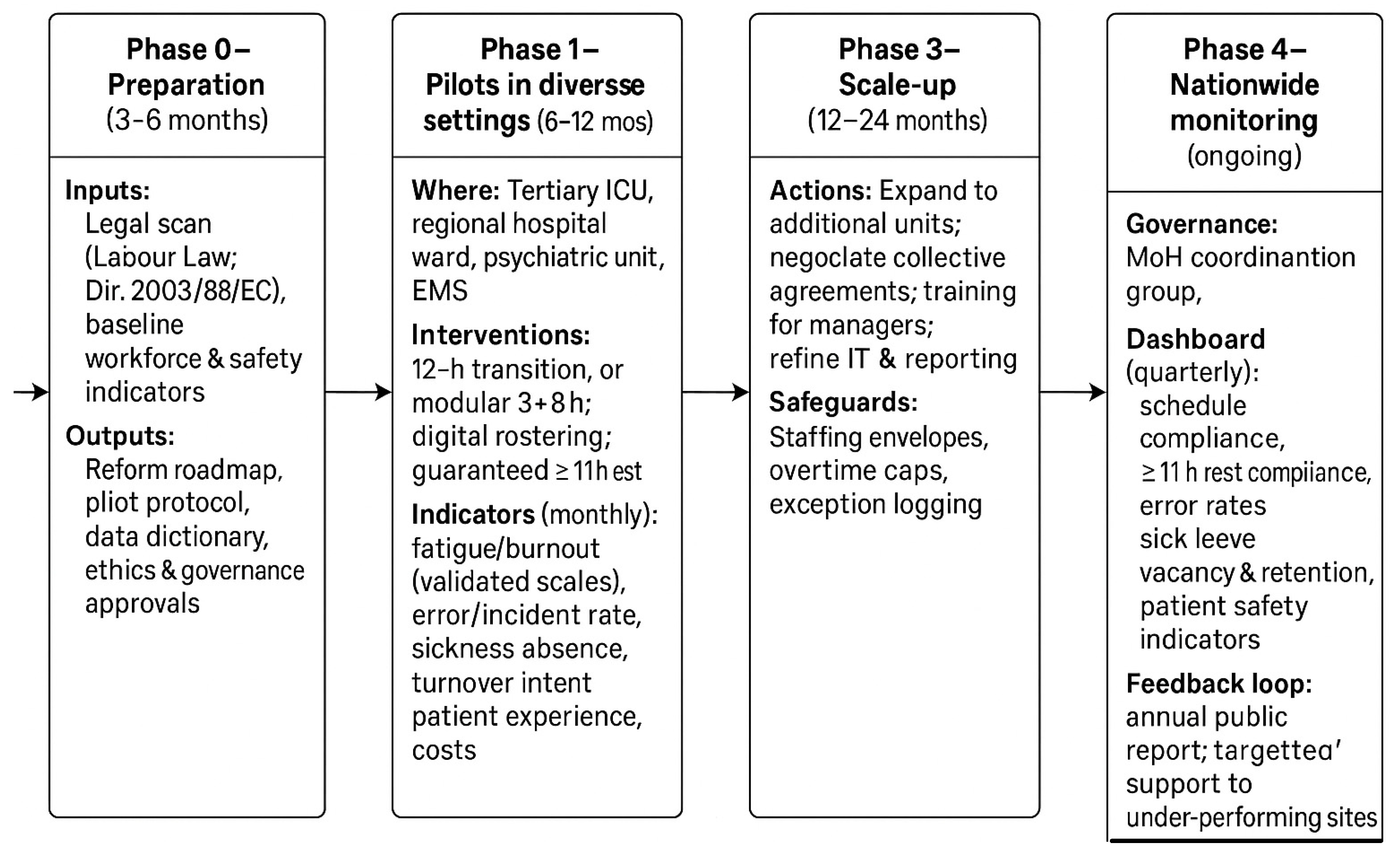

- Monitoring and sustainability: Without a strong data infrastructure, early reforms risk losing momentum. Mitigation: Establish a national dashboard (as in Figure 1) to track compliance, rest, and patient safety indicators.

5.3. Barriers and Enabling Factors for Implementation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| EU | European Union |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ILO | International Labour Organization |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| JD-R | Job Demands–Resources |

| RSU | Riga Stradiņš University |

| SLI | State Labour Inspectorate |

| SPKC | Centre for Disease Prevention and Control |

| ANA | American Nurses Association |

| EC | European Council |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| USA | United States of America |

References

- Cabinet of Ministers. Order No. 1194 of 18 December 2024: “Health Workforce Development Strategy Plan 2025–2029”; Government of the Republic of Latvia: Riga, Latvia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. State of the World’s Nursing 2020: Investing in Education, Jobs and Leadership; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stimpfel, A.W.; Sloane, D.M.; Aiken, L.H. The longer the shifts for hospital nurses, the higher the levels of burnout and patient dissatisfaction. Health Aff. 2012, 31, 2501–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Dall’Ora, C.; Simon, M.; Ball, J.; Lindqvist, R.; Rafferty, A.M.; Schoonhoven, L.; Tishelman, C. Nurses’ shift length and overtime working in 12 European countries: The association with perceived quality of care and patient safety. Med. Care 2014, 52, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinkoff, A.M.; Johantgen, M.; Storr, C.L.; Gurses, A.P.; Liang, Y.; Han, K. Nurses’ work schedule characteristics, nurse staffing, and patient mortality. Nurs. Res. 2011, 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.D.; Rogers, A.E.; Hwang, W.T.; Zhang, Y. Effects of critical care nurses’ work hours on vigilance and patient safety. Am. J. Crit. Care 2006, 15, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.H.; Sermeus, W.; Van den Heede, K.; Sloane, D.M.; Busse, R.; McKee, M.; Bruyneel, L.; Rafferty, A.M.; Griffiths, P.; Moreno-Casbas, T.; et al. Patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of hospital care: Cross-sectional surveys of nurses and patients in 12 countries in Europe and the United States. BMJ 2012, 344, e1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger-Brown, J.; Trinkoff, A.M. Is it time to pull the plug on 12-hour shifts? Part 1. The evidence. J. Nurs. Adm. 2010, 40, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health at a Glance: Europe 2023—State of Health in the EU Cycle; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riga Stradins University. Study on the Sustainability of the Nursing Profession in Latvia; Institute of Public Health, Riga Stradins University: Riga, Latvia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of Latvia. In the New Academic Year, Additional State-Funded Study Places in the “Nursing” Programme at Universities. 6 June 2023. Available online: https://lvportals.lv/dienaskartiba/352371-jaunaja-macibu-gada-maszinibu-programma-augstskolas-bus-papildu-budzeta-vietas-2023 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Rogers, A.E.; Hwang, W.T.; Scott, L.D.; Aiken, L.H.; Dinges, D.F. The working hours of hospital staff nurses and patient safety. Health Aff. 2004, 23, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Ball, J.E.; Drennan, J.; Dall’Ora, C.; Jones, J.; Maruotti, A.; Pope, C.; Recio-Saucedo, A.; Simon, M. Nurse staffing and patient outcomes: Strengths and limitations of the evidence to inform policy and practice. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 63, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Ora, C.; Griffiths, P.; Ball, J.; Simon, M.; Aiken, L.H. Association of 12-hour shifts and nurse fatigue with patient and nurse outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e065912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Health Workforce Development, Attraction, Recruitment and Retention in Rural and Remote Areas; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516204 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- European Commission. Action Plan for the EU Health Workforce; Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/142f07f4-03f8-417e-85a2-4062ca81ded7_en?filename=ev_20150617_co01_en.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound). Working Time in the Health Sector: Comparative Report of the EU and Selected Countries; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/report/2020/working-time-in-the-health-sector (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Nordic Council of Ministers. Working Environments in the Nordic Countries—Past, Present and Future; Nordic Council: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019; Available online: https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1265618/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Dall’Ora, C.; Ball, J.; Reinius, M.; Griffiths, P. Burnout in nursing: A theoretical review and reformulation. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (BMAS). Arbeitszeitgesetz (Working Time Act); BMAS: Berlin, Germany, 2003; Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/arbzg/ (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Ministère du Travail. Temps de Travail dans la Fonction Publique Hospitalière; Government of France: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://travail-emploi.gouv.fr (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- NHS Employers. Working Patterns in the NHS: Flexibility and Shift Systems; NHS Confederation: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.nhsemployers.org (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Canadian Nurses Association (CNA). The Impact of Shift Work on Nurses; CNA: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://www.cna-aiic.ca (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Safe Work Australia. Fatigue Management in Healthcare: Best Practice Models; Safe Work Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2020. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- American Nurses Association (ANA). Nurse Staffing and Work Hours: National Guidelines and Innovations; ANA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nurse-staffing/nurse-staffing-measures/ (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Valsts Darba Inspekcija. Pārskats par Darba Tiesību Normu Ievērošanu Veselības Aprūpes Nozarē; Valsts darba inspekcija: Rīga, Latvia, 2023. Available online: https://www.vdi.gov.lv/lv/media/2592/download?attachment (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Saeima of the Republic of Latvia. Darba Likums (Labour Law); Likumi.lv: Rīga, Latvia, 2001; Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/26019-darba-likums (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Veselības Ministrija. Par Ārstniecības Personu Atalgojuma Struktūru un Piemaksu Sistēmu; Veselības Ministrija: Rīga, Latvia, 2022; Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/332751-sabiedribas-veselibas-pamatnostadnes-2021-2027-gadam (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–Resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F. The Job Demands–Resources model: Ten years later. J. Manag. Psychol. 2021, 36, 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.; Louch, G.; Dunning, A.; Johnson, O.; Grange, A.; Reynolds, C.; Hall, L.; O’Hara, J. Burnout mediates the association between symptoms of depression and patient safety perceptions in nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 1667–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnentag, S.; Fritz, C. Recovery from work stress: Recent developments and future research. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2022, 9, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, G.N.; Greenhaus, J.H. Untangling work–family enrichment and conflict: A review and research agenda. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 750–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Working Time and Health: Evidence and Policy Recommendations; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/who-guidelines (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health at a Glance: Europe 2024; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Slimību Profilakses un Kontroles Centrs (SPKC). Veselības Aprūpes Darbinieku Psihosociālo Risku Izvērtējums; SPKC: Rīga, Latvia, 2022. Available online: https://www.spkc.gov.lv (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Valsts Darba Inspekcija (SLI). Pārskats par Darba Tiesību Normu Ievērošanu Veselības Aprūpes nozarē; Valsts Darba Inspekcija: Rīga, Latvia, 2024. Available online: https://www.vdi.gov.lv (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Griffiths, P.; Ball, J.; Dall’Ora, C.; Simon, M.; Aiken, L.H. Nurse staffing, fatigue and patient safety: European policy implications. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2024, 154, 104534. [Google Scholar]

- Walt, G.; Gilson, L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: The central role of policy analysis. Health Policy Plan. 1994, 9, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Erwin, P.J.; Shanafelt, T.D. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016, 388, 2272–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Burn-Out An “Occupational Phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/burn-out/en/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Mealer, M.; Burnham, E.L.; Goode, C.J.; Rothbaum, B.; Moss, M. The prevalence and impact of post-traumatic stress disorder and burnout syndrome in nurses. Depress. Anxiety 2009, 26, 1118–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, C.H.; Batcheller, J.; Schroeder, K.; Donohue, P. Burnout and resilience among nurses practicing in high-intensity settings. Am. J. Crit. Care 2015, 24, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centrālā Statistikas Pārvalde (CSP). Latvijas Iedzīvotāju Skaits, Struktūra un Demogrāfiskās Prognozes; CSP: Rīga, Latvia, 2023. Available online: https://www.csp.gov.lv (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Veselības Ministrija. Informatīvais Ziņojums par Ārstniecības Personu Sagatavošanu un Piesaisti Ārstniecības Iestādēm; Veselības Ministrija: Rīga, Latvia, 2023. Available online: https://www.vm.gov.lv/lv/media/12000/download?attachment (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Trinkoff, A.M.; Johantgen, M.; Muntaner, C.; Le, R. Staffing and worker injury in nursing homes. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 1220–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hignett, S.; Crumpton, E. Evidence-based ergonomics education for nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rīgas Stradiņa Universitāte. Māsu darba Apmierinātība un Profesionālās Ilgtspējas Faktori Latvijā; RSU Sabiedrības Veselības Institūts: Rīga, Latvia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). Psychosocial Risks and Stress at Work. 2014. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/themes/psychosocial-risks-and-stress (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Goh, J.; Sinsky, C. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 1826–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrian, J.; Lamond, N.; van den Heuvel, C.; Pincombe, J.; Rogers, A.E.; Dawson, D. A pilot study of the safety implications of Australian nurses’ sleep and work hours. Chronobiol. Int. 2006, 23, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockley, S.W.; Landrigan, C.P.; Barger, L.K.; Czeisler, C.A. When policy meets physiology: The challenge of reducing resident work hours. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2007, 449, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.; Steege, L.M. Nurse fatigue and nurse, patient safety, and organizational outcomes: A systematic review. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 43, 1171–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Nurses Association (ANA). Addressing Nurse Fatigue to Promote Safety and Health: Joint Responsibilities of Registered Nurses and Employers to Reduce Risks; ANA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/official-position-statements/id/addressing-nurse-fatigue-to-promote-safety-and-health/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Zaranko, B.; Propper, C.; Stoye, G. Nurse staffing and inpatient mortality in the English NHS. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2023, 32, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veselības Inspekcija. Pacientu Drošības un kvalitātes Pārskats: Novērojumi Latvijas Ārstniecības Iestādēs; Veselības Inspekcija: Rīga, Latvia, 2021. Available online: https://www.vi.gov.lv/lv/jaunums/par-veselibas-aprupes-kvalitati-2024-gada-veselibas-inspekcija-kopuma-izskatits-491-iesniegums?utm_source=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Tucker, A.L.; Spear, S.J. Operational failures and interruptions in hospital nursing. Health Serv. Res. 2006, 41, 643–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, C.C.; Baldwin, C.M.; Berger, A.M.; Chasens, E.R.; Landis, C.A.; Redeker, N.S.; Scott, L.D. Position statement: Reducing fatigue associated with sleep deficiency and work hours in nurses. Nurs. Outlook 2021, 69, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, S.; Tyrrell, M. Stress in emergency departments: Experiences of nurses and doctors. Emerg. Nurse 2013, 21, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eurofound. Working Conditions in Healthcare During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Frontline Workers in the Spotlight; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/report/2021/working-conditions-in-healthcare-during-the-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Dyrbye, L.N.; West, C.P.; Sinsky, C.A.; Goeders, L.E.; Satele, D.V.; Shanafelt, T.D. Medical licensure questions and physician reluctance to seek care for mental health conditions. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, A.; Gustavsson, P.; Hultell, D. A prospective study of nurses’ intentions to leave the profession during their first five years of practice in Sweden. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manser, T. Teamwork and patient safety in dynamic domains of healthcare: A review of the literature. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2009, 53, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Patient Safety: Global Action Plan 2021–2030—Towards Eliminating Avoidable Harm in Health Care; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240032705 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Veselības inspekcija. Ekspertu Ziņojums: Latvijas Republikas Veselības Aprūpes Pakalpojumu un Sociālās Aprūpes Uzraudzības Izvērtējums; Veselības inspekcija: Rīga, Latvia, 2018. Available online: https://www.vi.gov.lv/sites/vi/files/content/documents/eurinspect-zinojums-latviesu-valoda.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Dawson, D.; Reid, K. Fatigue, alcohol and performance impairment. Nature 1997, 388, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, A.; Feyer, A.M. Moderate sleep deprivation produces impairments in cognitive and motor performance equivalent to legally prescribed levels of alcohol intoxication. Occup. Environ. Med. 2000, 57, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.I.; Sheu, S.J.; Yu, S.; Wei, I.L.; Chen, C.H. Nurses relate the contributing factors involved in medication errors. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musy, S.N.; Endrich, O.; Leichtle, A.B.; Griffiths, P.; Nakas, C.T.; Simon, M. The association between nurse staffing and inpatient mortality: A shift-level retrospective longitudinal study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 120, 103950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahey, D.C.; Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.M.; Clarke, S.P.; Vargas, D. Nurse burnout and patient satisfaction. Med. Care 2004, 42, II57–II66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Directive 2003/88/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 November 2003 concerning certain aspects of the organisation of working time. Off. J. Eur. Union 2003, 299, 9–19. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32003L0088 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Griffiths, P.; Ball, J.E.; Drennan, J.; Recio-Saucedo, A.; Dall’Ora, C. Nurse staffing levels, missed vital signs and mortality in hospitals: Retrospective longitudinal observational study. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2020, 29, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indicator | Latvia | EU Average | Nordic Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nurses per 1000 population [10] | 4.2 | 8.5 | 10.1 |

| Share of nurses working >12 h [11,18] | 60% | 28% | 10% |

| Reported burnout (moderate–high) [16,37] | 57% | 38% | 25% |

| Reported clinical errors (%) [16,17,27,28] | 18% | 9% | 6% |

| Legal cap for shift duration [18] | None | ≤12 h | ≤12 h |

| Country/Region | Standard Shift Duration | Rest Requirements | Implementation Strategy | Reported Effects (Examples) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweden | 8–12 h | ≥11 h between shifts | National labour agreements; strong unit-level co-design | ↓ burnout; ↑ retention; ↓ errors |

| Norway | ≤12 h | ≥11 h; weekly rest | Pilots in university hospitals → wider rollout | ↑ satisfaction; ↓ sick leave |

| Denmark/Finland | 8–12 h | EU/ILO aligned | Collective agreements; robust rostering IT | Better continuity; stable costs |

| Germany | 8–10 (12) h | Mandatory daily/weekly rest | Working Time Act; strict overtime accounting | ↓ med errors; improved compliance |

| France | 7–8 h (35 h week) | Mandated rest/limits | Policy + hospital protocols; exceptions audited | ↑ predictability; mixed on 12 h |

| United Kingdom | 8 h & 12 h (rotations) | Mandated rest | Local agreements; split-shift pilots | Mixed; staff preference matters |

| Canada | 12 h common; mixed 8/12 h | Mandated rest | Local policies; fatigue training | ↓ incidents with robust rest |

| Australia/New Zealand | 8/10/12 h | Mandated rest | Compressed weeks in some units | ↑ days off; needs discipline |

| United States | 12 h prevalent; hybrids | Rest varies by state | Large systems adopt hybrid models | ↑ efficiency when coupled with rest |

| Latvia (current) | up to 24 h | No statutory ≤12 h cap | Historical practice; shortages | ↑ fatigue; safety concerns |

| Model | Satisfaction (%) | Patient Safety (%) | Efficiency (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 h shift model | 75 | 78 | 80 | Available in units with lots of resources |

| Max. 16 h shifts | 68 | 72 | 74 | Transitional solution |

| Modular (2 × 6 h or 3 × 8 h) | 82 | 88 | 86 | High level of coordination required |

| Flexible shifts | 90 | 93 | 92 | Staff planning platform required |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cerela-Boltunova, O.; Klavina, K. Transition from 24-Hour Shifts to Safer Work Schedules for Nurses in Latvian Healthcare: Policy Analysis and Recommendations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111736

Cerela-Boltunova O, Klavina K. Transition from 24-Hour Shifts to Safer Work Schedules for Nurses in Latvian Healthcare: Policy Analysis and Recommendations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111736

Chicago/Turabian StyleCerela-Boltunova, Olga, and Kristine Klavina. 2025. "Transition from 24-Hour Shifts to Safer Work Schedules for Nurses in Latvian Healthcare: Policy Analysis and Recommendations" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111736

APA StyleCerela-Boltunova, O., & Klavina, K. (2025). Transition from 24-Hour Shifts to Safer Work Schedules for Nurses in Latvian Healthcare: Policy Analysis and Recommendations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111736