Trauma Exposure as a “Driver” of Change in Mental Health Problems Among Youth with Multiple Admissions to Juvenile Detention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Present Study

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Alcohol/Drug Use (ADU)

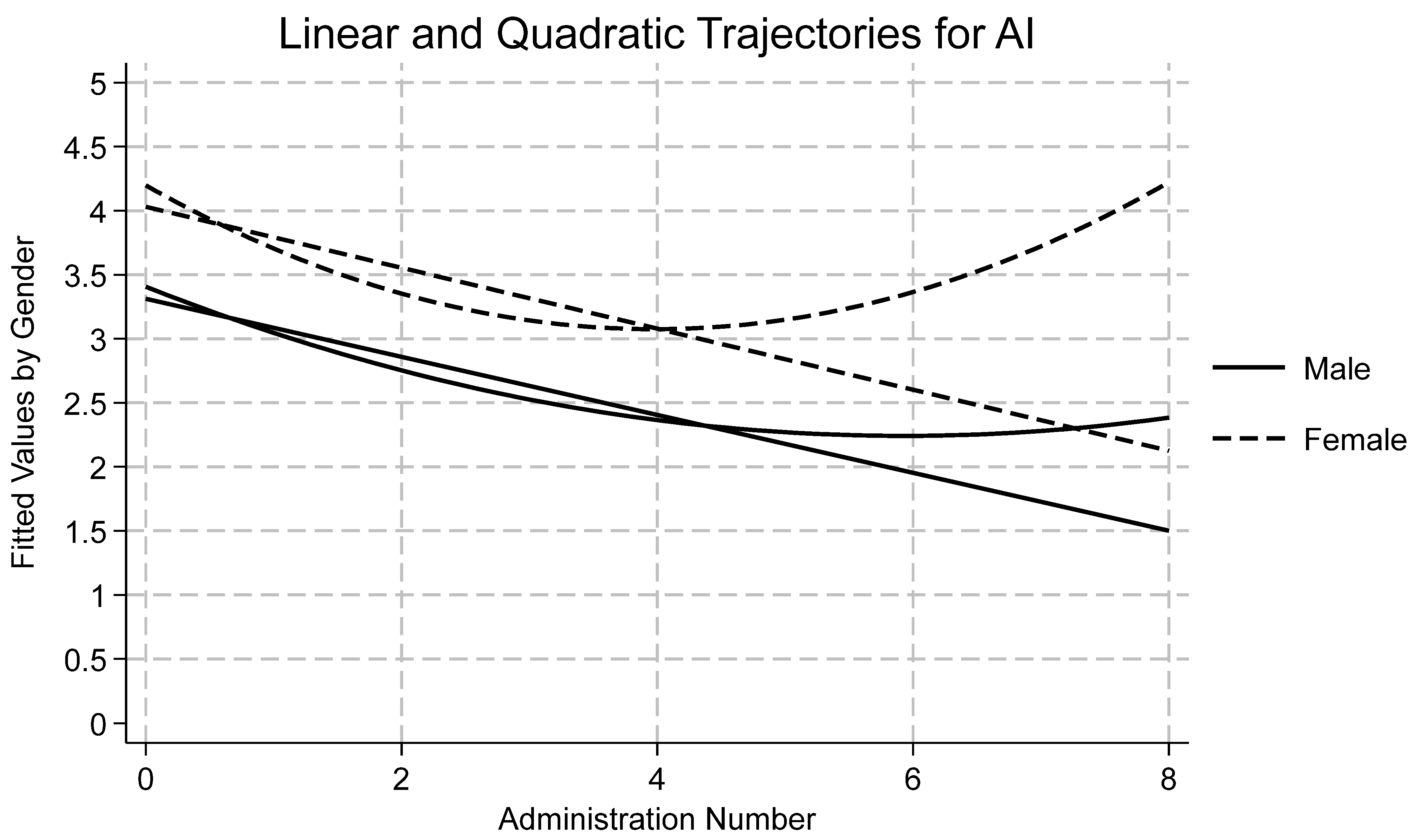

4.2. Anger/Irritability (AI)

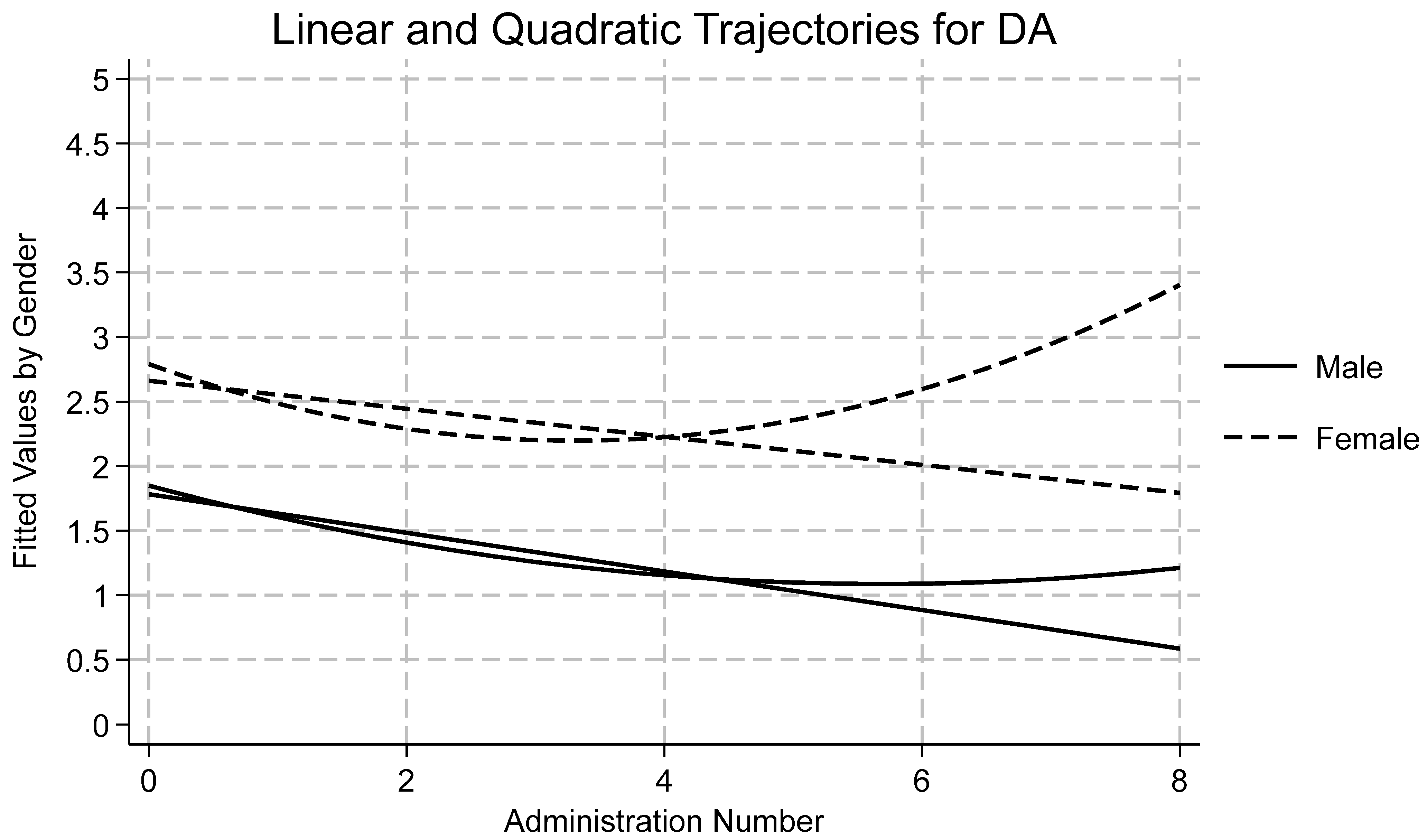

4.3. Depressed/Anxious (DA)

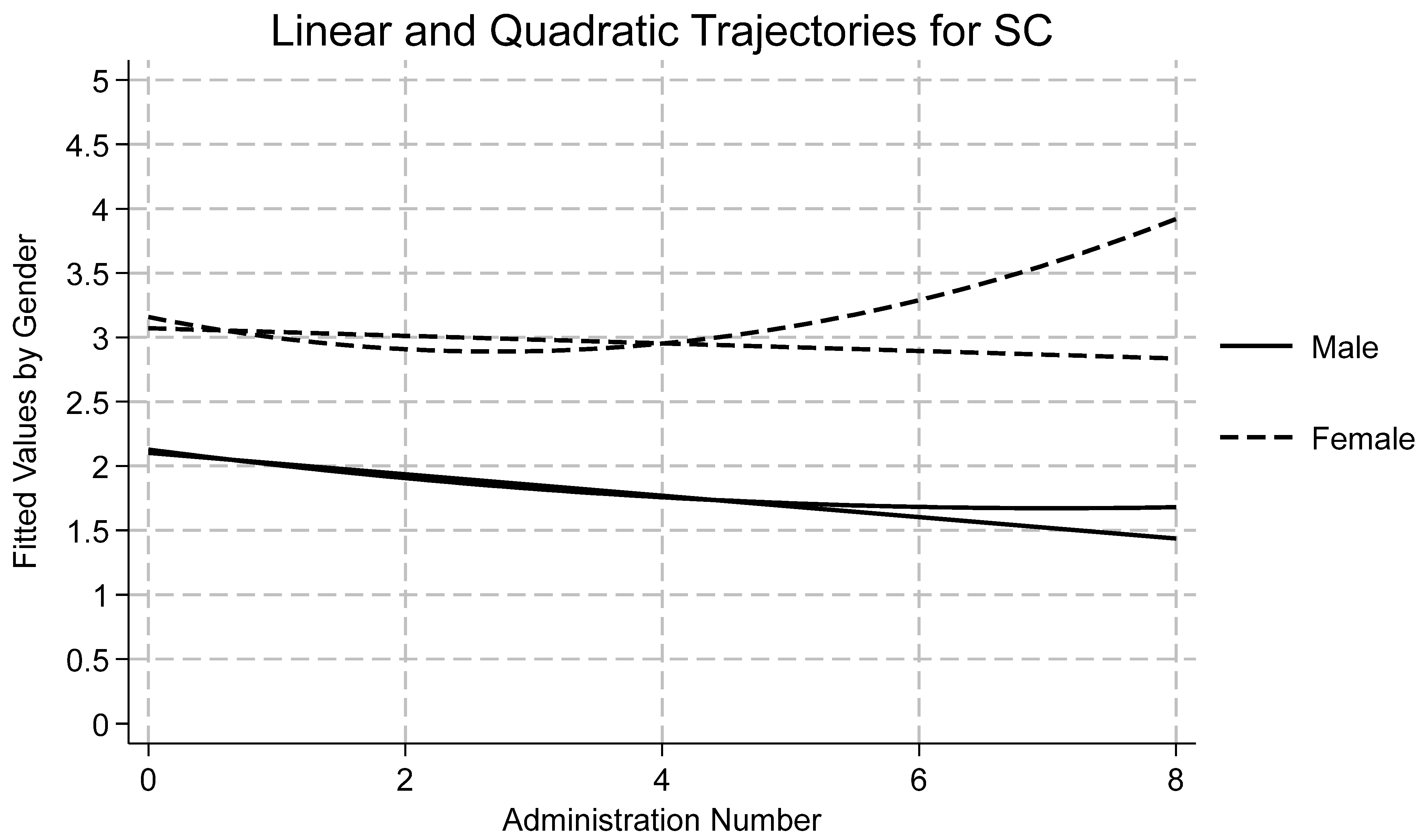

4.4. Somatic Complaints (SC)

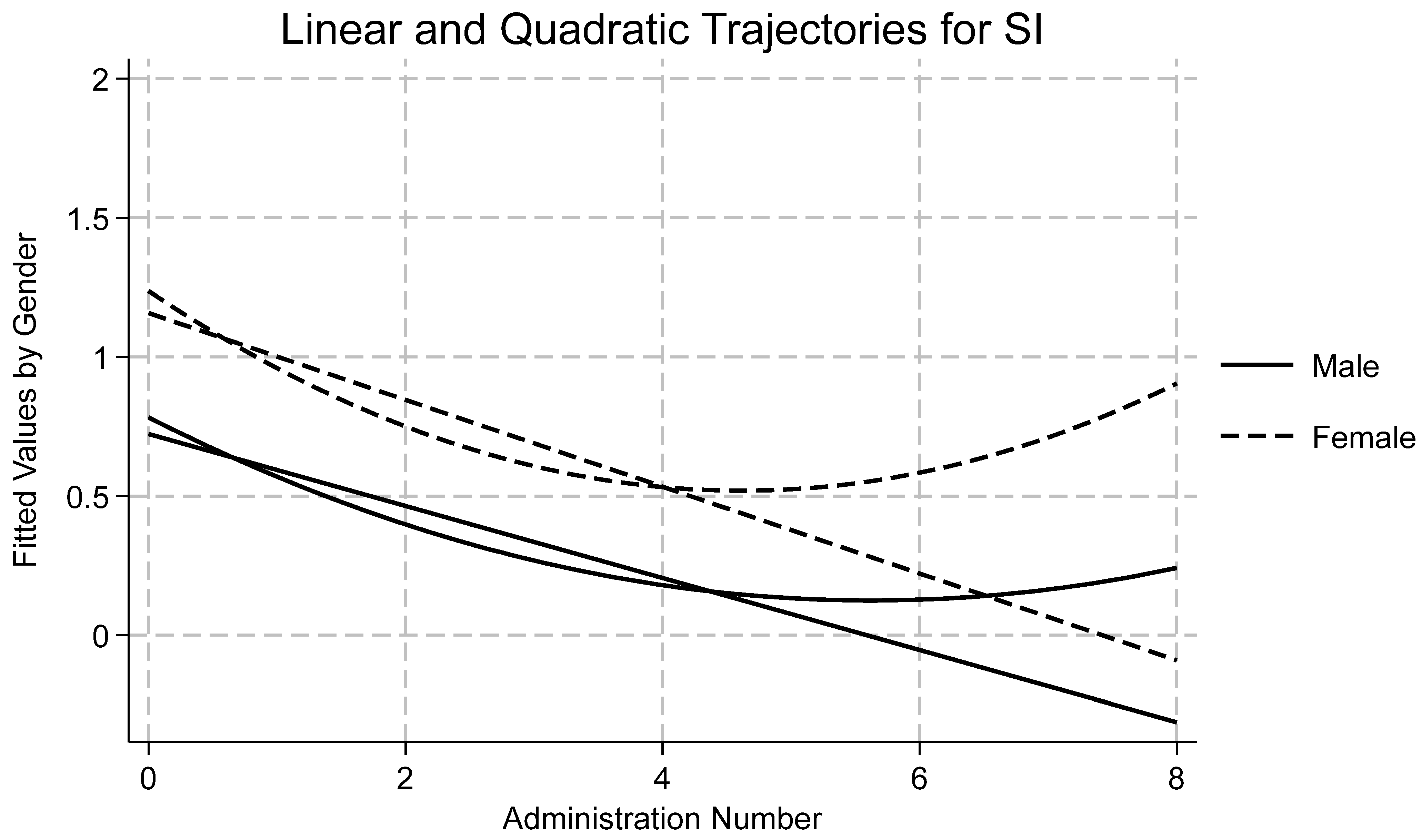

4.5. Suicidal Ideation (SI)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Koenen, K.C.; Hill, E.D.; Petukhova, M.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Kessler, R.C. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 52, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abram, K.M.; Teplin, L.A.; Charles, D.R.; Longworth, S.L.; McClelland, G.M.; Dulcan, M.K. Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma in youth in juvenile detention. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2004, 61, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duron, J.F.; Williams-Butler, A.; Mattson, P.; Boxer, P. Trauma exposure and mental health needs among adolescents involved with the juvenile justice system. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 37, NP15700–NP15725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerig, P.K.; Becker, S.P. Trauma and girls’ delinquency. In Delinquent Girls: Context, Relationships, and Adaptation; Miller, S., Leve, L., Kerig, P.K., Eds.; Springer Books: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 119–143. [Google Scholar]

- Dierkhising, C.B.; Ko, S.J.; Woods-Jaeger, B.; Briggs, E.C.; Lee, R.; Pynoos, R.S. Trauma histories among justice-involved youth: Findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2013, 4, 20274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglivio, M.T.; Wolff, K.T.; Piquero, A.R.; Epps, N. The relationship between adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and juvenile offending trajectories in a juvenile offender sample. J. Crim. Justice 2015, 43, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglivio, M.T.; Wolff, K.T.; DeLisi, M.; Jackowski, K. The Role of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Psychopathic Features on Juvenile Offending Criminal Careers to Age 18. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2020, 18, 337–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerig, P.K.; Becker, S.P. 12 Early abuse and neglect as risk factors for the development of criminal and antisocial behavior. In The Development of Criminal and Antisocial Behavior; Morizot, J., Kazemian, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerridge, B.T.; Chou, S.P.; Huang, B.; Harford, T.C. Sociodemographic characteristics, adverse childhood experiences, and substance use and psychiatric disorders among adolescent-limited, adult-onset, life-course-persistent offenders and nonoffenders in a general population survey. Crime. Delinq. 2020, 66, 1729–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widom, C.S. Long-term impact of childhood abuse and neglect on crime and violence. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2017, 24, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Fukushima-Tedor, M.; Mallett, C.A.; Quinn, M.I.; Quinn, L.M. Examining Trauma and Crime by Gender and Sexual Orientation among Youth: Findings from the Add Health National Longitudinal Study. Crime. Delinq. 2021, 68, 814–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetz, C.L.; Surko, M.; Bart, A.; Guo, F.; Alexander, A.; Camarano, V.; Daniels, D.; Havens, J.; Horwitz, S.M. The risk for readmission to juvenile detention: The role of trauma exposure and trauma-related mental health disorders. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2024, 17, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.P.; Kerig, P.K.; Lim, J.Y.; Ezechukwu, R.N. Mental health problems and recidivism among adolescent offenders: Interrelations of gender, ethnicity, age, and posttraumatic stress. In Psychological Trauma and Juvenile Delinquency; Kerig, P.K., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, M.A. Adverse childhood experiences and justice-involved youth: The effect of trauma and programming on different recidivistic outcomes. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2019, 17, 354–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitopoulos, N.A.; Peterson-Badali, M.; Brown, S.; Skilling, T.A. The relationship between trauma, recidivism risk, and reoffending in male and female juvenile offenders. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2019, 12, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yohros, A. Examining the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and juvenile recidivism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2023, 24, 1640–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cauffman, E. Understanding the female offender. Future Child. 2008, 18, 119–142. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20179981 (accessed on 29 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Barnert, E.S.; Dudovitz, R.; Nelson, B.B.; Coker, T.R.; Biely, C.; Li, N.; Chung, P.J. How does incarcerating young people affect their adult health outcomes? Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20162624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heard-Garris, N.; Sacotte, K.A.; Winkelman, T.N.; Cohen, A.; Ekwueme, P.O.; Barnert, E.; Carnethon, M.; Davis, M.M. Association of childhood history of parental incarceration and juvenile justice involvement with mental health in early adulthood. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1910465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambie, I.; Randell, I. The impact of incarceration on juvenile offenders. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, E.; Magram, J.; Kennedy, T.D. Systematic review: Impact of juvenile incarceration. Child Prot. Pract. 2024, 3, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitrieva, J.; Monahan, K.C.; Cauffman, E.; Steinberg, L. Arrested development: The effects of incarceration on the development of psychosocial maturity. Dev. Psychopathol. 2012, 24, 1073–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendel, R.A. No Place for Kids: The Case for Reducing Juvenile Incarceration; Annie E. Casey Foundation: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2011; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10244/1035 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- McKenna, N.C.; Anderson, V.R. Pathways to—But not through? Revisiting the trauma and recidivism relationship among system-involved youth. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2024, 22, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.M.; Trulson, C.R.; DeLisi, M.; Caudill, J.W. Toward an understanding of the impact of adverse childhood experiences on the recidivism of serious juvenile offenders. Am. J. Crim. Justice 2020, 45, 1024–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvaso, C.G.; Cale, J.; Whitten, T.; Day, A.; Singh, S.; Hackett, L.; Delfabbro, P.H.; Ross, S. Associations between adverse childhood experiences and trauma among young people who offend: A systematic literature review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 23, 1677–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerig, P.K.; Becker, S.P. From internalizing to externalizing: Theoretical models of the processes linking PTSD to juvenile delinquency. In Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Causes, Symptoms and Treatment; Egan, S.J., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, F.W. The impact of trauma on child development. Juv. Fam. Court. J. 2006, 57, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendall, S.; Eastwood, O.; Spelman, T.; McGorry, P.; Hickie, I.; Yung, A.R.; Amminger, P.; Wood, S.J.; Pantelis, C.; Purcell, R.; et al. Childhood trauma is prevalent and associated with co-occurring depression, anxiety, mania and psychosis in young people attending Australian youth mental health services. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2023, 57, 1518–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Elhai, J.D.; Connor, D.F.; Frueh, B.C. Poly-victimization and risk of posttraumatic, depressive, and substance use disorders and involvement in delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 46, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplin, L.A.; Abram, K.M.; McClelland, G.M.; Dulcan, M.K.; Mericle, A.A. Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2002, 59, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Colich, N.L.; Rodman, A.M.; Weissman, D.G. Mechanisms linking childhood trauma exposure and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic model of risk and resilience. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogg, B.; Gardoki-Souto, I.; Valiente-Gómez, A.; Rosa, A.R.; Fortea, L.; Radua, J.; Amann, B.L.; Moreno-Alcázar, A. Psychological trauma as a transdiagnostic risk factor for mental disorder: An umbrella meta-analysis. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 273, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerig, P.K. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Childhood and Adolescence: A Developmental Psychopathology Perspective; Momentum Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S.E.; Abram, K.M.; Aaby, D.; Welty, L.J.; Arzu, J.L.; Salvati, J.M.; Teplin, L.A. Incarceration and subsequent psychosocial outcomes: A 16-year longitudinal study of youth after detention. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Kerig, P.K.; Ford, J.D.; Alexander, A.R.; Modrowski, C.A. Interventions for trauma-affected youth in the juvenile justice system: An overview of diagnostic, ethical, and clinical challenges, and evidence-based treatments. Psychol. Inj. Law 2024, 17, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, W.T.; Ellis, B.J. Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary–developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Dev. Psychopathol. 2005, 17, 271–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaylord-Harden, N.K.; Bai, G.J.; Simic, D. Examining a dual–process model of desensitization and hypersensitization to community violence in African American male adolescents. J. Trauma Stress 2017, 30, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, D.J.; Ford, J.D.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J. Early life trauma exposure and stress sensitivity in young children. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 38, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zgoba, K.M.; Low, S. Aggression and academic misconduct among justice-involved youth: The roles of facility environment, adverse childhood experiences and social competency. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2024, 22, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stimmel, M.A.; Cruise, K.R.; Ford, J.D.; Weiss, R.A. Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology, and aggression in male juvenile offenders. Psychol. Trauma 2013, 6, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, A.E.; Bounoua, N.; Rose, R.E.; Sadeh, N.; Javdani, S. Profiles of risk for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors among system-impacted girls of color. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 63, 898–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerig, P.K.; Schindler, S.R. Engendering the evidence base: A critical review of the conceptual and empirical foundations of gender-responsive interventions for girls’ delinquency. Laws 2013, 2, 244–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.C.; Muno, A.; Sullivan-Colglazier, C. Principles in practice: A multistate study of gender-responsive reforms in the juvenile justice system. Crime. Delinq. 2015, 61, 742–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn, M.A.; Agnew, R.; Fishbein, D.; Miller, S.; Winn, D.M.; Dakoff, G.; Kruttschnitt, C.; Giordano, P.; Gottfredson, D.C.; Payne, A.A.; et al. Causes and Correlates of Girls’ Delinquency; U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Conrad, S.M.; Tolou-Shams, M.; Rizzo, C.J.; Placella, N.; Brown, L.K. Gender differences in recidivism rates for juvenile justice youth: The impact of sexual abuse. Law Hum. Behav. 2014, 38, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cauffman, E.; Gillespie, M.L.; Beardslee, J.; Davis, F.; Hernandez, M.; Williams, T. Adolescent contact, lasting impact? Lessons learned from two longitudinal studies spanning 20 years of developmental science research with justice-system-involved youths. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2023, 24, 133–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zane, S.N.; Pupo, J.A. Disproportionate minority contact in the juvenile justice system: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Justice Q. 2021, 38, 1293–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearhart, M.C.; Bender, A.; Barnhart, S.; Berg, K.A.; Jones, C. Youth profiles of police-initiated post-traumatic stress symptomatology. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2021, 39, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, E.L.; Haft, S.L.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Q. Systematic review: The association between race-related stress and trauma and emotion dysregulation in youth of color. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 62, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaggers, J.W.; Lau, C.; Howey, W.; Kerig, P.K. Associations between traumatic experiences and mental health risk profiles in youth with justice system involvement. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2025, 23, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.; Mendez, L.; Kerig, P.K. Moral injury as a transdiagnostic risk factor for mental health problems in detained youth. Crim. Justice Behav. 2024, 51, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauffman, E. A state-wide screening of mental health symptoms among juvenile offenders in detention. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 43, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, F.D.; Havens, J.; Surko, M.; Weinberger, E.; Baetz, C.; Moaveni, M.; Bart, A.; Marr, M.; Quinlan, C.; Horwitz, S.M. Post-traumatic stress and related symptoms among juvenile detention residents: Results from intake screening. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 92, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisso, T.; Barnum, R. Massachusetts Youth Screening Instrument Version 2: User’s Manual and Technical Report; Professional Resource Press: Riverside, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J.D.; Chapman, J.F.; Pearson, G.; Borum, R.; Wolpaw, J.M. Psychometric status and clinical utility of the MAYSI-2 with girls and boys in juvenile detention. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2008, 30, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, E.P.; Bechtold, J.; Kelly, E.L.; Cauffman, E. Mental health screening in juvenile justice settings: Evaluating the utility of the Massachusetts Youth Screening Instrument, Version 2. Crim. Justice Policy Rev. 2018, 29, 849–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannella, L.; Eno Louden, J.; Kennealy, P.; Kang, T. Psychometric properties of the MAYSI-2 among Latino adolescent offenders. Crim. Justice Behav. 2018, 45, 1252–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerig, P.K.; Moeddel, M.A.; Becker, S.P. Assessing the sensitivity and specificity of the MAYSI-2 for detecting trauma among youth in juvenile detention. Child Youth Care Forum 2011, 40, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauffman, E.; Lexcen, F.J.; Goldweber, A.; Shulman, E.P.; Grisso, T. Gender differences in mental health symptoms among delinquent and community youth. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2007, 5, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggers, J.W.; Cambron, C.; Kerig, P.K.; Osteen, P. Measurement equivalence across multiple administrations of the Massachusetts Youth Screening Instrument. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2021, 43, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansournia, M.A.; Nazemipour, M.; Naimi, A.; Collins, G.S.; Campbell, M.J. Reflection on modern methods: Demystifying robust standard errors for epidemiologists. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, B.T.; Welch, K.B.; Galecki, A.T. Linear Mixed Models: A Practical Guide Using Statistical Software, 3rd ed.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.; Fairbrother, M.; Jones, K. Fixed and random effects models: Making an informed choice. Qual. Quant. 2019, 53, 1051–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.M. Analysis of longitudinal data: The integration of theoretical model, temporal design, and statistical model. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2006, 57, 505–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, N.M.; Ware, J.H. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics 1982, 38, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzmaurice, G.M.; Laird, N.M.; Ware, J.H. Applied Longitudinal Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, A.; Hill, J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stata. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bliese, P.D.; Maltarich, M.A.; Hendricks, J.L. Back to basics with mixed-effects models: Nine take-away points. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S.; Johnson, P.C.D.; Schielzeth, H. The coefficient of determination R2 and intra-class correlation coefficient from generalized linear mixed-effects models revisited and expanded. J. R. Soc. Interface 2017, 14, 20170213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. The review of normality tests for distributing data. J. Korean Stat. Soc. 2013, 42, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.J.; West, S.G.; Finch, J.F. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalsma, M.C.; Tong, Y.; Lane, K.; Katz, B.; Rosenman, M.B. Use of outpatient care by juvenile detainees upon community reentry: Effects of mental health screening and referral. Psychiatr. Serv. 2012, 63, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akpanekpo, E.I.; Srasuebkul, P.; Butler, T.; Trollor, J.N.; Kasinathan, J.; Kenny, D.; Greenberg, D.M.; Simpson, M.; Gaskin, C.; Jones, J.; et al. Association between mental health treatment and reoffending among justice-involved youths. Psychiatr. Serv. 2025, 76, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, M.J.; Abram, K.M.; Aaby, D.A.; Welty, L.J.; Teplin, L.A. Inequities in mental health services: A 16-year longitudinal study of youth in the justice system. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 63, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, G.; Grisso, T.; Terry, A.; Banks, S. Sex and race differences in mental health symptoms in juvenile justice: The MAYSI-2 national meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelman, T.N.; Frank, J.W.; Binswanger, I.A.; Pinals, D.A. Health conditions and racial differences among justice-involved adolescents, 2009 to 2014. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.S.; Cicchetti, D. Developmental cascades. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010, 22, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layne, C.M.; Beck, C.J.; Rimmasch, H.; Southwick, J.S.; Moreno, M.A.; Hobfoll, S.E. Promoting “resilient” posttraumatic adjustment in childhood and beyond: “Unpacking” life events, adjustment trajectories, resources, and interventions. In Treating Traumatized Children: Risk, Resilience, and Recovery; Brom, D., Pat-Horenczyk, R., Ford, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 13–47. [Google Scholar]

- Weems, C.F.; McCurdy, B.H.; Scozzafava, M.D. Toward a developmental model of continuity and change in PTSD symptoms following exposure to traumatic and adverse experiences. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2023, 16, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado, L.M.; Shah, R.S. Protecting Youth from Self-Incrimination When Undergoing Screening, Assessment, and Treatment Within the Juvenile Justice System; Juvenile Law Center: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kerig, P.K.; Mendez, L.; Mozley, M.M. Forensic assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder, Complex PTSD, and other trauma-related disorders in juvenile justice contexts. In Handbook of Psychological Injury and Law; Young, G., Bailey, T., Giromini, L., Soble, J., Rogers, R., Levitt, B., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 101–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeve, M.; McReynolds, L.S.; Wasserman, G.A.; McMillan, C. The influence of mental health disorders on severity of reoffending in juveniles. Crim. Justice Behav. 2013, 40, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleeven, A.T.H.; Hilterman, E.L.B.; Mulder, E.A.; Popma, A.; de Vries Robbé, M. Trajectories of justice involved youth: Changing risk and protective factors for violence. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2025, 23, 160–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branson, C.E.; Baetz, C.L.; Horwitz, S.M.; Hoagwood, K.E. Trauma-informed juvenile justice systems: A systematic review of definitions and core components. Psychol. Trauma 2017, 9, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listenbee, R.L.; Torre, J. Defending Childhood: Report of the Attorney General’s National Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence; U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Baetz, C.L.; Branson, C.E.; Weinberger, E.; Rose, R.E.; Petkova, E.; Horwitz, S.M.; Hoagwood, K.E. The effectiveness of PTSD treatment for adolescents in the juvenile justice system: A systematic review. Psychol. Trauma 2021, 14, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenson, J.; Brodsky, S.L.; Perlin, M.L. Trauma-informed forensic mental health assessment: Practical implications, ethical tensions, and alignment with therapeutic jurisprudence principles. Psychol. Public Policy Law 2022, 28, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feierman, J.; Fine, L. Trauma and Resilience: A New Look at Legal Advocacy for Youth in the Juvenile Justice and Child Welfare Systems; Juvenile Law Center: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- White, H.R.; Shi, J.; Hirschfield, P.; Mun, E.Y.; Loeber, R. Effects of institutional confinement for delinquency on levels of depression and anxiety among male adolescents. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2010, 8, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggers, J.W.; Modrowski, C.A.; Kerig, P.K.; Kilshaw, R.E.; Cambron, C.; Allen, A.K. Latent profiles of responding on the Massachusetts Youth Screening Instrument-2 subscale scores by race/ethnicity among juvenile justice-involved boys and girls. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2023, 21, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeve, M.; McReynolds, L.S.; Wasserman, G.A. Service referral for juvenile justice youths: Associations with psychiatric disorder and recidivism. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2014, 41, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplin, L.A.; Welty, L.J.; Abram, K.M.; Dulcan, M.K.; Washburn, J.J. Prevalence and persistence of psychiatric disorders in youth after detention: A prospective longitudinal study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 1031–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A.E.; Padgaonkar, N.T.; Galván, A.; Frick, P.J.; Steinberg, L.; Cauffman, E. Characterizing trajectories of anxiety, depression, and criminal offending in male adolescents over the 5 years following their first arrest. Dev. Psychopathol. 2023, 35, 570–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelleher, I.; Harley, M.; Lynch, F.; Arseneault, L.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Cannon, M. Associations between childhood trauma, bullying and psychotic symptoms among a school-based adolescent sample. Br. J. Psychiatry 2008, 193, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varese, F.; Smeets, F.; Drukker, M.; Lieverse, R.; Lataster, T.; Viechtbauer, W.; Read, J.; van Os, J.; Bentall, R.P. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: A meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr. Bull. 2012, 38, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierkhising, C.B.; Lane, A.; Natsuaki, M.N. Victims behind bars: A preliminary study of abuse during juvenile incarceration and post-release social and emotional functioning. Psychol. Public Policy Law 2014, 20, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLisi, M.; Drury, A.J.; Kosloski, A.E.; Caudill, J.W.; Conis, P.J.; Anderson, C.A.; Vaughn, M.G.; Beaver, K.M. The cycle of violence behind bars: Traumatization and institutional misconduct among juvenile delinquents in confinement. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2010, 8, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlin, E.M. Moving beyond prison rape: Assessing sexual victimization among youth in custody. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2019, 47, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallett, C.A. The incarceration of seriously traumatized adolescents in the USA: Limited progress and significant harm. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2015, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ADU Mean (SE) | AI Mean (SE) | DA Mean (SE) | SC Mean (SE) | SI Mean (SE) | TE Mean (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIME 1 (n = 5615) | 2.29 (0.03) | 2.99 (0.04) | 1.85 (0.03) | 2.32 (0.02) | 0.67 (0.02) | 1.84 (0.02) |

| TIME 2 (n = 2289) | 2.52 (0.05) | 2.67 (0.05) | 1.57 (0.04) | 2.10 (0.04) | 0.41 (0.02) | 1.69 (0.03) |

| TIME 3 (n = 1255) | 2.67 (0.07) | 2.63 (0.07) | 1.44 (0.05) | 2.15 (0.05) | 0.33 (0.03) | 1.61 (0.04) |

| TIME 4 (n = 709) | 2.76 (0.10) | 2.52 (0.10) | 1.38 (0.07) | 2.04 (0.07) | 0.29 (0.03) | 1.58 (0.06) |

| TIME 5 (n = 392) | 2.76 (0.13) | 2.33 (0.13) | 1.42 (0.09) | 1.94 (0.10) | 0.26 (0.04) | 1.46 (0.08) |

| TIME 6 (n = 210) | 2.95 (0.18) | 2.45 (0.17) | 1.38 (0.12) | 1.95 (0.14) | 0.18 (0.05) | 1.46 (0.10) |

| TIME 7 (n = 112) | 2.71 (0.24) | 2.09 (0.21) | 1.26 (0.15) | 1.92 (0.19) | 0.21 (0.06) | 1.46 (0.14) |

| TIME 8 (n = 52) | 2.81 (0.36) | 2.04 (0.28) | 1.02 (0.19) | 2.19 (0.31) | 0.13 (0.08) | 1.33 (0.21) |

| N (%) | Cronbach’s Alpha | |||||

| Female | 1499 (26.7%) | ADU | 0.81 | |||

| Male | 4116 (73.3%) | AI | 0.82 | |||

| White | 2826 (50.3% | DA | 0.72 | |||

| Black | 334 (5.9%) | SC | 0.73 | |||

| Hispanic | 1955 (34.8%) | SI | 0.86 | |||

| Other | 500 (8.9%) | TE-girls | 0.69 | |||

| TE-boys | 0.61 |

| Anger/Irritability | Depression/Anxiety | Somatic Complaints | Suicidal Ideation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIXED EFFECTS | ||||

| Intercept | 3.13 (0.13) * | 1.47 (0.09) * | 2.13 (0.09) * | 0.71 (0.06) * |

| Time | −0.44 (0.08) * | −0.24 (0.05) * | −0.14 (0.05) * | −0.22 (0.03) * |

| Time2 | 0.05 (0.01) * | 0.03 (0.01) * | 0.02 (0.01) * | 0.02 (0.01) * |

| Trauma | 0.29 (0.03) * | 0.25 (0.02) * | 0.18 (0.02) * | 0.09 (0.01) * |

| Gender (female) | 0.53 (0.11) * | 0.73 (0.08) * | 0.9 (0.08) * | 0.34 (0.05) * |

| Black | −0.13 (0.24) | −0.06 (0.13) | −0.63 (0.14) * | −0.10 (0.08) |

| Hispanic | −0.58 (0.1) * | −0.24 (0.07) * | −0.6 (0.07) * | −0.2 (0.04) * |

| Other | 0.01 (0.17) | −0.25 (0.1) * | −0.6 (0.11) * | −0.3 (0.06) * |

| RANDOM EFFECTS | ||||

| Participant | 3.89 (0.39) | 1.08 (0.23) | 1.22 (0.02) | 0.16 (0.01) |

| Time | 0.21 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.02) | <0.001 (<0.001) |

| Trauma | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.06 (0.01) |

| FIT | ||||

| Log likelihood | −11,340.47 | −9675.68 | −9527.07 | −7551.84 |

| ICC | 0.57 (0.03) | 0.37 (0.06) | 0.44 | 0.15 (0.06) |

| AIC | 22,710.94 | 19,381.36 | 19,084.11 | 15,127.69 |

| BIC | 22,808.80 | 19,479.22 | 1981.97 | 15,205.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kerig, P.K.; Jaggers, J.W.; Alexander, A.R. Trauma Exposure as a “Driver” of Change in Mental Health Problems Among Youth with Multiple Admissions to Juvenile Detention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111710

Kerig PK, Jaggers JW, Alexander AR. Trauma Exposure as a “Driver” of Change in Mental Health Problems Among Youth with Multiple Admissions to Juvenile Detention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111710

Chicago/Turabian StyleKerig, Patricia K., Jeremiah W. Jaggers, and Ava R. Alexander. 2025. "Trauma Exposure as a “Driver” of Change in Mental Health Problems Among Youth with Multiple Admissions to Juvenile Detention" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111710

APA StyleKerig, P. K., Jaggers, J. W., & Alexander, A. R. (2025). Trauma Exposure as a “Driver” of Change in Mental Health Problems Among Youth with Multiple Admissions to Juvenile Detention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111710