Heterogeneous Effects of Income on Physical and Mental Health of the Elderly: A Regression Discontinuity Design Based on China’s New Rural Pension Scheme

Abstract

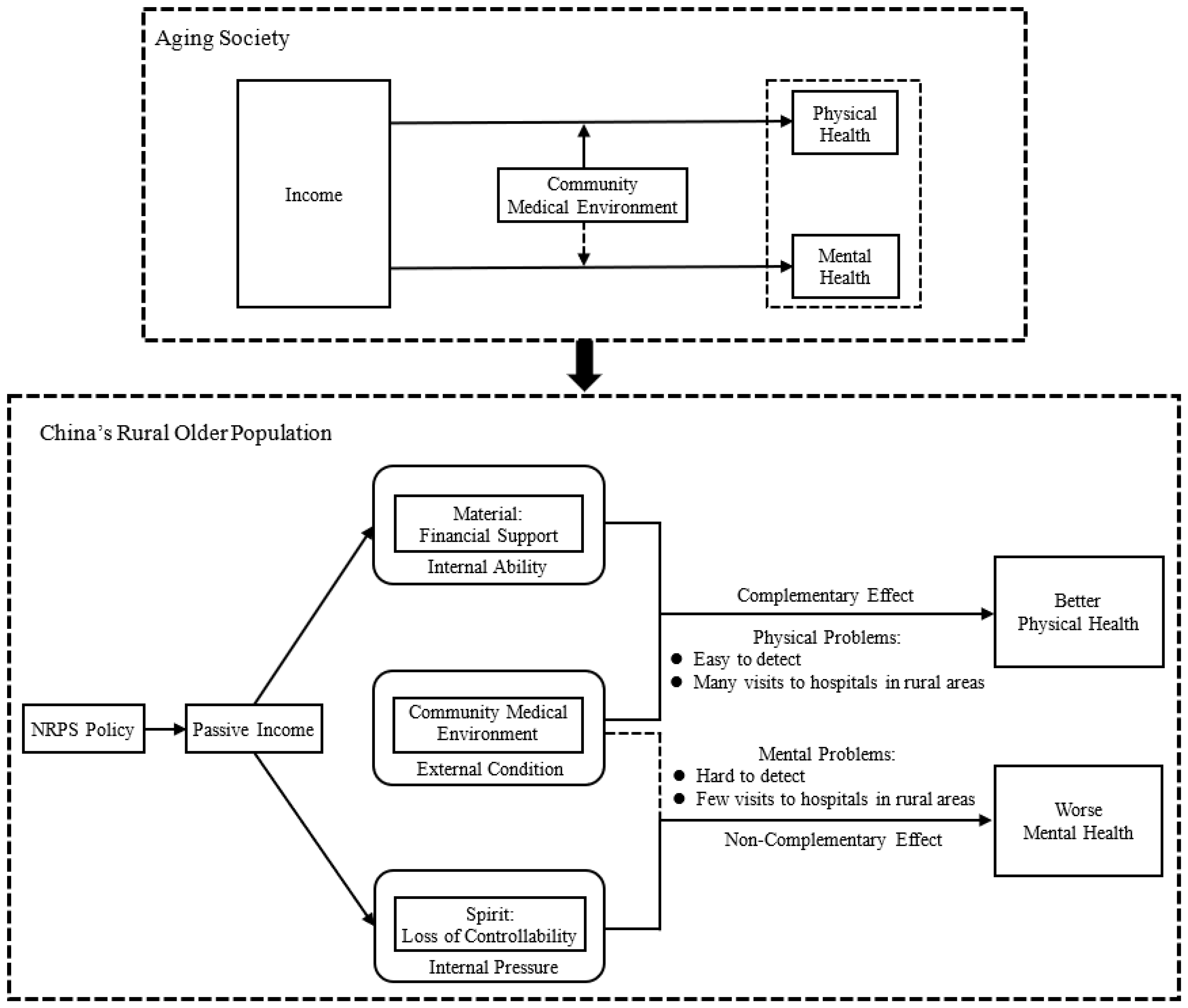

1. Introduction

2. China’s New Rural Pension Scheme

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Variables and Measures

3.3. Model

3.4. Summary Statistics

4. Empirical Results

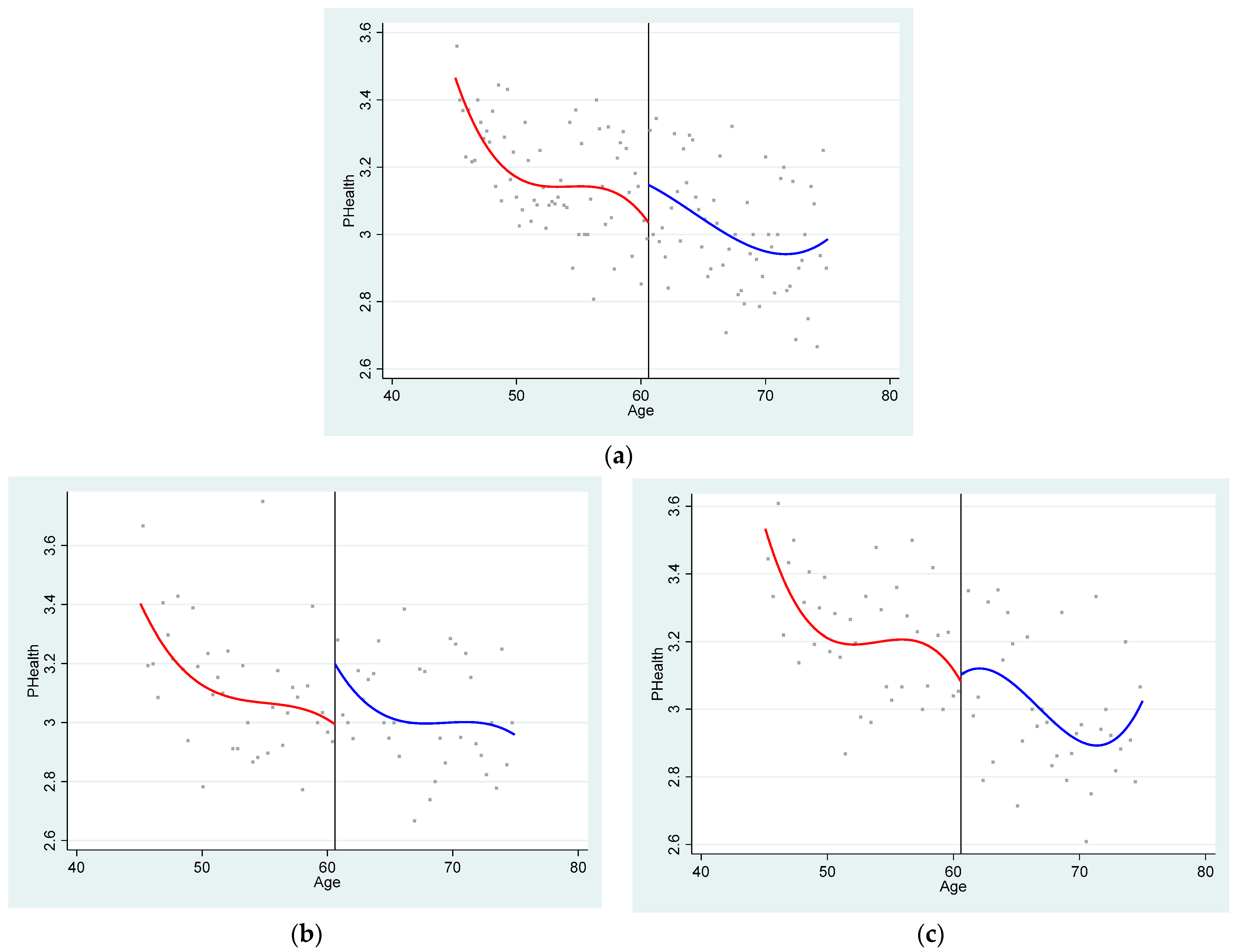

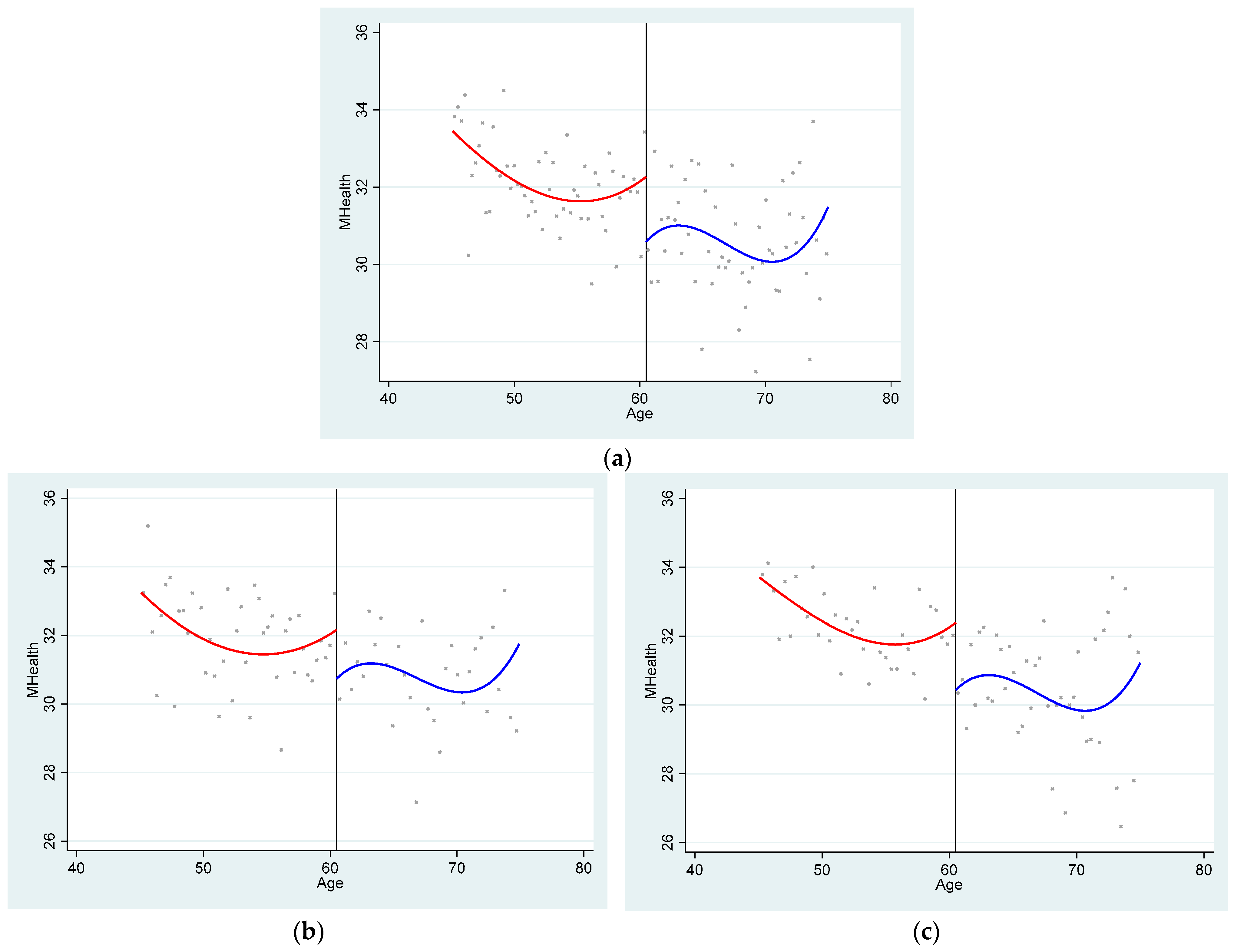

4.1. Graphical Analysis

4.2. Regression Analysis

4.3. Validity Check

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN. World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Lloyd-Sherlock, P.; Ebrahim, S.; Geffen, L.; McKee, M. Bearing the brunt of COVID-19: Older people in low and middle income countries. BMJ Open 2020, 368, m1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Tran, C. The extension of social security coverage in developing countries. J. Dev. Econ. 2012, 99, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettner, S.L. New evidence on the relationship between income and health. J. Health Econ. 1996, 15, 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.V.; Goldman, N. Socioeconomic differences in health among older adults in Mexico. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 1372–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijters, P.; Haisken-DeNew, J.P.; Shields, M.A. The causal effect of income on health: Evidence from German reunification. J. Health Econ. 2005, 24, 997–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.G.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z. The health implications of social pensions: Evidence from China’s new rural pension scheme. J. Comp. Econ. 2018, 46, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Wu, Y.C. Does welfare stigma exist in China? Policy evaluation of the minimum living security system on recipients’ psychological health and wellbeing. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 205, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.P. The impact of socioeconomic status on health over the life-course. J. Hum. Resour. 2007, 48, 739–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, S.E.; Evans, W.N. The effect of income on mortality: Evidence from the social security notch. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2006, 88, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Durden, E. Socioeconomic status and age trajectories of health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 2489–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, A.; Roux, I.L.; Menendez, A. Medical Compliance and Income-Health Gradients. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 94, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Jin, G.Z. Does health insurance coverage lead to better health and educational outcomes? Evidence from rural China. J. Health Econ. 2012, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Zhai, F.H. Public assistance, economic prospect, and happiness in urban China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 132, 451–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, M. Estimating the effect of income on health and mortality using lottery prizes as an exogenous source of variation in income. J. Hum. Resour. 2005, 40, 144–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rablen, M.D.; Oswald, A.J. Mortality and immortality: The Nobel Prize as an experiment into the effect of status upon longevity. J. Health Econ. 2008, 27, 1462–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apouey, B.; Clark, A.E. Winning big but feeling no better? The effect of lottery prizes on physical and mental health. Health Econ. 2015, 24, 516–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Thomas, D. Psychological health before, during, and after an economic crisis: Results from Indonesia, 1993–2000. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2008, 23, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D.; Von Wachter, T. Job displacement and mortality: An analysis using administrative data. Q. J. Econ. 2009, 124, 1265–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Ruhm, J. Inheritances, health and death. Health Econ. 2012, 21, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.N.; Garthwaite, C.L. Giving mom a break: The impact of higher EITC payments on maternal health. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2014, 6, 258–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Zhou, Z.L.; Zhao, Y.X.; Shen, C.; Lai, S.; Nawaz, R.; Gao, J.M. Evaluating the effect of hierarchical medical system on health seeking behavior: A difference-in-differences analysis in China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 268, 113372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Good Health Adds Life to Years—Global Brief for World Health Day 2012; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- WHO. China Country Assessment Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Shi, S.J. Left to market and family–again? Ideas and the development of the rural pension policy in China. Soc. Policy Adm. 2006, 40, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. China’s urban and rural old age security system: Challenges and options. China World Econ. 2006, 14, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, C. The power of social pensions: Evidence from China’s new rural pension scheme. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2021, 13, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Chen, S.; Pan, G.; Zheng, L. Social pension scheme and health inequality: Evidence from China’s new rural social pension scheme. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 837431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, M.; Gong, J.; Zheng, X.; Zhuang, J. Does new rural pension scheme decrease elderly labor supply? Evidence from CHARLS. China Econ. Rev. 2016, 41, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z. The heterogeneous impact of pension income on elderly living arrangements: Evidence from China’s new rural pension scheme. J. Popul. Econ. 2018, 31, 155–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Fang, X.; Brown, D.S. Social pensions and child health in rural China. J. Dev. Stud. 2020, 56, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Zheng, X.; Yang, H. The fertility effects of public pension: Evidence from the new rural pension scheme in China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Xiong, D. Do social assistance programs promote the use of clean cooking fuels? Evidence from China’s new rural pension scheme. Energy Policy 2023, 182, 113741. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.Q.; Zhou, X.; Meng, Y.Y. The impact of religious beliefs on the health of the residents-Evidence from China. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2020, 35, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.C.; Chen, B.K. Can “public pension system” substitutes “family mutual insurance”? Econ. Res. J. 2014, 11, 102–115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Imbens, G.; Kalyanaraman, K. Optimal bandwidth choice for the Regression Discontinuity Estimator. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2012, 79, 933–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depp, C.A.; Jeste, D.V. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 14, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaupel, J.W. Biodemography of human ageing. Nature 2010, 464, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Lemieux, T. Regression Discontinuity Designs in economics. J. Econ. Lit. 2010, 48, 281–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Kong, L.Z.; Wu, F.; Bai, Y.M.; Burton, R. Chronic diseases 4: Preventing chronic diseases in China. Lancet 2005, 366, 1821–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, O. Chinese Family and Society; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Y. China’s youth in NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training): Evidence from a national survey. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2020, 688, 171–189. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R. Handbook of Self-Determination Research; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.; Cheung, S.; Chio, J.H.; Chan, M.S. Cultural meaning of perceived control: A meta-analysis of locus of control and psychological symptoms across 18 cultural regions. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 152–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infurna, F.J.; Gerstorf, D. Perceived control relates to better functional health and lower cardio-metabolic risk: The mediating role of physical activity. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turiano, N.A.; Chapman, B.P.; Agrigoroaei, S.; Infurna, F.J.; Lachman, M. Perceived control reduces mortality risk at low, not high, education levels. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, E.J.; Rodin, J. The effects of choice and enhanced personal responsibility for the aged: A field experiment in an institutional setting. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1976, 34, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.W.; He, G.J.; Pan, Y.P. Mitigating the air pollution effect? The remarkable decline in the pollution-mortality relationship in Hong Kong. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2020, 101, 102316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Definition | Whether Receiving NRPS Pension | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Receiving NRPS Pension | Receiving NRPS Pension | ||||||

| N (%) | Mean | SD | N (%) | Mean | SD | ||

| PHealth | Individual’s self-assessed health status, 1 = very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = fair, 4 = good, 5 = very good. | 2745 (56.6) | 3.18 | 1.00 | 2101 (43.4) | 3.03 | 0.96 |

| 1 | 117 (4.3) | 1 | 0 | 101 (4.8) | 1 | 0 | |

| 2 | 411 (15.0) | 2 | 0 | 414 (19.7) | 2 | 0 | |

| 3 | 1461 (53.2) | 3 | 0 | 1131 (53.8) | 3 | 0 | |

| 4 | 361 (13.2) | 4 | 0 | 230 (10.9) | 4 | 0 | |

| 5 | 395 (14.3) | 5 | 0 | 225 (10.7) | 5 | 0 | |

| MHealth | CES-D10, the score is ranging from 10 to 40. The higher the score, the better the mental health. | 2745 (56.6) | 32.17 | 6.41 | 2101 (43.4) | 30.81 | 6.89 |

| 10–20 | 180 (6.5) | 16.84 | 2.94 | 222 (10.6) | 16.86 | 2.61 | |

| 21–30 | 721 (26.3) | 26.45 | 2.79 | 611 (29.1) | 26.23 | 2.89 | |

| 31–40 | 1844 (67.2) | 35.90 | 2.76 | 1268 (60.3) | 35.45 | 2.75 | |

| MEnvironment | Total number of all kinds of hospitals in community. | 2745 (56.6) | 2.04 | 2.18 | 2101 (43.4) | 1.97 | 2.55 |

| 1–5 | 2549 (92.8) | 1.60 | 1.25 | 1970 (93.8) | 1.49 | 1.22 | |

| 6–10 | 158 (5.8) | 6.99 | 1.11 | 98 (4.6) | 7.17 | 1.28 | |

| ≥11 | 38 (1.4) | 12.63 | 1.91 | 33 (1.6) | 14.82 | 7.82 | |

| Age | Running variable, the age of respondents in 2015. | 2745 (56.6) | 52.28 | 6.23 | 2101 (43.4) | 67.53 | 6.43 |

| Gender | 1 = male; 0 = female | 2745 (56.6) | 0.50 | 0.51 | 2101 (43.4) | 0.53 | 0.53 |

| Martial | 1 = Married; 0 = Single | 2745 (56.6) | 0.94 | 0.23 | 2101 (43.4) | 0.80 | 0.40 |

| Child | LOG (the number of surviving children of the respondents) | 2745 (56.6) | 1.14 | 0.34 | 2101 (43.4) | 1.33 | 0.37 |

| Income | LOG (total income (CNY) of individual in 2014) | 2745 (56.6) | 9.42 | 1.21 | 2101 (43.4) | 8.44 | 1.49 |

| Transfer | The net amount (CNY) of (transfer payments received from children–transfer payments to children) in 2014. We take the natural logarithm of individual transfer. | 2745 (56.6) | −0.35 | 5.93 | 2101 (43.4) | 2.47 | 5.14 |

| Twater | LOG (the quantity of tap water in local community) | 2745 (56.6) | 2.90 | 3.00 | 2101 (43.4) | 2.95 | 3.00 |

| Economic | The economic level of local community, the score ranges from 1 to 7. The higher the score, the better the economic status. | 2745 (100) | 3.61 | 1.28 | 2101 (43.4) | 3.57 | 1.29 |

| Panel A: The effect of NRPS on physical health | ||||

| Variables | Age Range | |||

| +/− 2.5 | +/− 2.0 | +/− 3.0 | +/− 4.0 | |

| The first stage of RD | ||||

| Age | 0.177 *** (3.381) | 0.120 ** (2.097) | 0.223 *** (4.604) | 0.307 *** (7.243) |

| The second stage of RD | ||||

| NRPS | 1.500 * (1.930) | 2.687 * (1.695) | 0.958 * (1.799) | 0.396 (1.183) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 963 | 788 | 1132 | 1421 |

| Panel B: The effect of NRPS on mental health | ||||

| Variables | Age Range | |||

| +/− 2.8 | +/− 2.0 | +/− 3.0 | +/− 4.0 | |

| The first stage of RD | ||||

| Age | 0.290 *** (5.093) | 0.188 *** (2.795) | 0.318 *** (5.865) | 0.407 *** (8.871) |

| The second stage of RD | ||||

| NRPS | −7.291 ** (−2.263) | −10.245 (−1.614) | −6.437 ** (−2.342) | −4.862 *** (−2.684) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 1049 | 759 | 1110 | 1399 |

| Panel A: Communities with better medical environment | ||||

| Variables | Age Range | |||

| +/− 3.5 | +/− 2.0 | +/− 3.0 | +/− 4.0 | |

| The first stage of RD | ||||

| Age | 0.306 *** (4.843) | 0.216 *** (2.779) | 0.273 *** (4.075) | 0.340 *** (5.697) |

| The second stage of RD | ||||

| NRPS | 1.000 ** (2.047) | 2.456 ** (2.160) | 1.341 ** (2.197) | 0.757 * (1.863) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 591 | 378 | 532 | 756 |

| Panel B: Communities with worse medical environment | ||||

| Variables | Age Range | |||

| +/− 3.0 | +/− 2.0 | +/− 4.0 | ||

| The first stage of RD | ||||

| Age | 0.179 *** (2.594) | 0.033 (0.398) | 0.279 *** (4.707) | |

| The second stage of RD | ||||

| NRPS | 0.404 (0.431) | 3.969 (0.369) | −0.031 (−0.056) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Obs. | 600 | 410 | 764 | |

| Panel A: Communities with better medical environment | ||||

| Variables | Age Range | |||

| +/− 4.4 | +/− 2.0 | +/− 3.0 | +/− 4.0 | |

| The first stage of RD | ||||

| Age | 0.413 *** (6.644) | 0.213 ** (2.310) | 0.304 *** (3.990) | 0.384 *** (5.834) |

| The second stage of RD | ||||

| NRPS | −4.400 * (−1.825) | −9.955 (−1.285) | −7.007 * (−1.692) | −4.976 * (−1.810) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 701 | 365 | 531 | 648 |

| Panel B: Communities with worse medical environment | ||||

| Variables | Age Range | |||

| +/− 3.5 | +/− 2.0 | +/− 3.0 | +/− 4.0 | |

| The first stage of RD | ||||

| Age | 0.397 *** (5.794) | 0.172 * (1.743) | 0.339 *** (4.419) | 0.433 *** (6.813) |

| The second stage of RD | ||||

| NRPS | −4.674 * (−1.680) | −10.32 (−1.015) | −5.578 (−1.544) | −4.530 * (−1.874) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs | 695 | 394 | 579 | 751 |

| Variables | Coef. | Std. Err. | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.524 | 0.743 | 0.480 |

| Marital | 0.637 | 0.523 | 0.223 |

| Child | 0.134 | 0.410 | 0.744 |

| Income | 2.342 | 4.671 | 0.616 |

| Transfer | −4.902 | 7.106 | 0.490 |

| Twater | −4.237 | 4.591 | 0.356 |

| Economic | −1.113 | 1.824 | 0.542 |

| Panel A: Physical health | ||||

| Variables | Age range | |||

| +/− 8.5 | +/− 7.0 | +/− 5.0 | +/− 3.0 | |

| NRPS | −0.066 (−0.759) | −0.061 (−0.639) | −0.024 (−0.217) | 0.025 (0.177) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 1756 | 1522 | 1153 | 719 |

| Panel B: Mental health | ||||

| Variables | Age range | |||

| +/− 6.8 | +/− 7.0 | +/− 5.0 | +/− 3.0 | |

| NRPS | 0.171 (0.236) | 0.164 (0.230) | 0.116 (0.190) | 0.602 (0.556) |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obs. | 1507 | 1522 | 1153 | 719 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ju, T.; Pan, M. Heterogeneous Effects of Income on Physical and Mental Health of the Elderly: A Regression Discontinuity Design Based on China’s New Rural Pension Scheme. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111709

Ju T, Pan M. Heterogeneous Effects of Income on Physical and Mental Health of the Elderly: A Regression Discontinuity Design Based on China’s New Rural Pension Scheme. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111709

Chicago/Turabian StyleJu, Tao, and Mengmeng Pan. 2025. "Heterogeneous Effects of Income on Physical and Mental Health of the Elderly: A Regression Discontinuity Design Based on China’s New Rural Pension Scheme" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111709

APA StyleJu, T., & Pan, M. (2025). Heterogeneous Effects of Income on Physical and Mental Health of the Elderly: A Regression Discontinuity Design Based on China’s New Rural Pension Scheme. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111709