Part 1: A Systematic Review to Describe Existing Cultural Adaptations in Lifestyle, Nutrition, and Physical Activity Programs for Native Hawaiian, CHamoru, and Filipino Populations

Abstract

1. Introduction

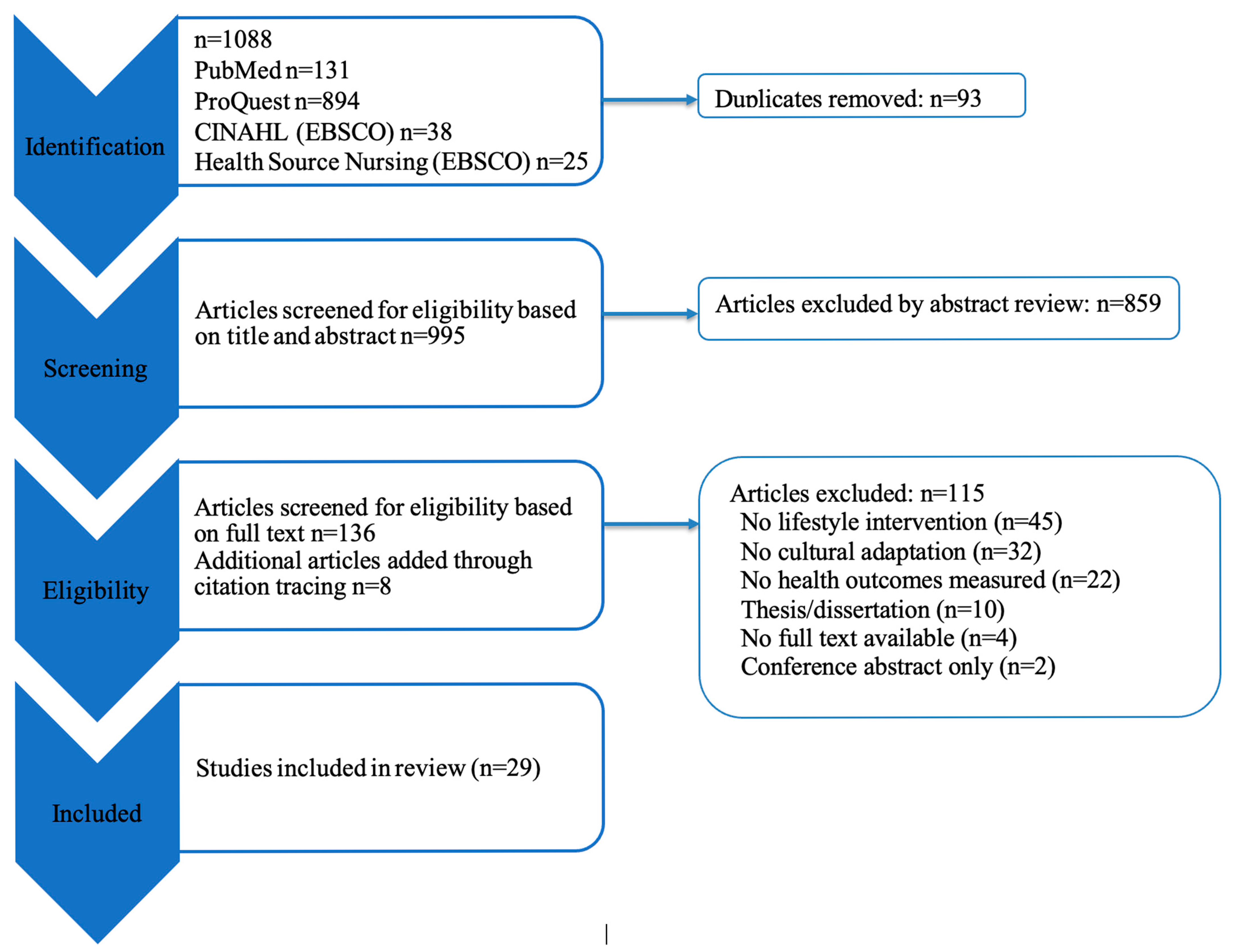

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Quality Appraisal

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Studies Included

3.2. Summary of Culturally Adapted Lifestyle Program Components

3.3. Quality of Research Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smedley, B.; Syme, S. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research. Am. J. Health Promot. 2001, 15, 149–166. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, L.M.S.; Chaves, S.C.L.; Santana, J.M.; Pereira, M. Public Policy Interventions for Preventing and Treating Obesity: Scoping Review. Nutr. Rev. 2023, 81, 1653–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.M.; Adeney, K.L.; Shinn, C.; Safranek, S.; Buckner-Brown, J.; Krause, L.K. Community Coalition-Driven Interventions to Reduce Health Disparities among Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD009905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suglia, S.F.; Shelton, R.C.; Hsiao, A.; Wang, Y.C.; Rundle, A.; Link, B.G. Why the Neighborhood Social Environment Is Critical in Obesity Prevention. J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2016, 93, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, H.S.; Franck, K.L.; Sweet, C.L. Community Coalitions for Change and the Policy, Systems, and Environment Model: A Community-Based Participatory Approach to Addressing Obesity in Rural Tennessee. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2019, 16, E120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandinetti, A.; Chang, H.K.; Chen, R.; Fujimoto, W.Y.; Rodriguez, B.L.; Curb, J.D. Prevalence of Overweight and Central Adiposity Is Associated with Percentage of Indigenous Ancestry among Native Hawaiians. Int. J. Obes. 1999, 23, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, R.T.L.; Paulino, Y.C.; Novotny, R.; Murphy, S.P. Diet and Obesity among Chamorro and Filipino Adults on Guam. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 17, 216–222. [Google Scholar]

- Maglalang, D.D.; Yoo, G.J.; Ursua, R.A.; Villanueva, C.; Chesla, C.A.; Bender, M.S. “I Don’t Have to Explain, People Understand”: Acceptability and Cultural Relevance of a Mobile Health Lifestyle Intervention for Filipinos with Type 2 Diabetes. Ethn. Dis. 2017, 27, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndugga, N.; Hill, L.; Published, S.A. Key Data on Health and Health Care for Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander People; KFF: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon, W.; Raj, A.; Reeve, E.; Guerrero, R.L.; Fesaitu, J.; Cateine, K.; Guignet, C. Processed Foods Available in the Pacific Islands. Glob. Health 2013, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Gordon-Larsen, P. The Nutrition Transition: Worldwide Obesity Dynamics and Their Determinants. Int. J. Obes. 2004, 28 (Suppl. S3), S2–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaman, R.R. Deterioration of Traditional Food Systems, Increasing Malnutrition and Food Dependency in the Pacific Islands. J. Food Nutr. 1982, 39, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Dela Cruz, R.; Wolfe, E.; Yonemori, K.M.; Fialkowski, M.K.; Wilkens, L.R.; Coleman, P.; Lameko-Mua, S.; Johnson, E.; Gilmatam, D.; Sigrah, C.; et al. Consumption of Traditional Fruits and Vegetables among Children in the US-Affiliated Pacific Region. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022, 6, nzac101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, R.; Braun, K.L.; Hughes, C.K. The Traditional Hawaiian Diet: A Review of the Literature. Pac. Health Dialog 2004, 11, 250–259. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.; Park, S.-Y.; Shvetsov, Y.B.; Wilkens, L.R.; Marchand, L.L.; Boushey, C.J.; Paik, H.-Y. Sex Differences in Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Factors Associated with Diet Quality in a Multiethnic Population. Nutrition 2019, 66, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varkevisser, R.D.M.; van Stralen, M.M.; Kroeze, W.; Ket, J.C.F.; Steenhuis, I.H.M. Determinants of Weight Loss Maintenance: A Systematic Review. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 171–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElfish, P.A.; Smith, L.; Sparks, K.; Bing, W.I.; Lang, S.; Estes, A.; Stephens, M. A Community-Based Participatory Approach to Promote Healthy Eating Among Marshallese. Hawaii J. Health Soc. Welf. 2019, 78, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaholokula, J.K.; Ing, C.T.; Look, M.A.; Delafield, R.; Sinclair, K. Culturally Responsive Approaches to Health Promotion for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2018, 45, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, R.; Davis, J.; Butel, J.; Boushey, C.J.; Fialkowski, M.K.; Nigg, C.R.; Braun, K.L.; Leon Guerrero, R.T.; Coleman, P.; Bersamin, A.; et al. Effect of the Children’s Healthy Living Program on Young Child Overweight, Obesity, and Acanthosis Nigricans in the US-Affiliated Pacific Region: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e183896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassel, K.D. Using the Social-Ecological Model as a Research and Intervention Framework to Understand and Mitigate Obesogenic Factors in Samoan Populations. Ethn. Health 2010, 15, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revisions to OMB’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15: Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/03/29/2024-06469/revisions-to-ombs-statistical-policy-directive-no-15-standards-for-maintaining-collecting-and (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Hezel, F.X. Deep in the Bloodstream: Historical Ties of the Marianas with the Philippines—Micronesian Seminar. Pac. Asia Inq. 2022, 13, 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pereda, N. Filipinos on Guam—Guampedia 2009. Available online: https://www.guampedia.com/filipinos-on-guam/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Hattori, A. Colonial Dis-Ease: US Navy Health Policies and the Chamorros of Guam, 1898–1941; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau, U.C. Chinese, Except Taiwanese, Was the Largest Asian Alone or in Any Combination Group; Nepalese Population Grew Fastest. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/09/2020-census-dhc-a-asian-population.html (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Bureau, U.C. 2020 Island Areas Censuses Data on Demographic, Social, Economic and Housing Characteristics Now Available for Guam. Available online: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/2020-island-areas-guam.html (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- McLaughlin, L.A.; Braun, K.L. Asian and Pacific Islander Cultural Values: Considerations for Health Care Decision Making. Health Soc. Work 1998, 23, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, A. Guam Culture, Immigration and the US Military Build-Up. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2010, 51, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick-Nietschmann, J. Pacific Islanders—Migration and Health. West J. Med. 1983, 139, 848–853. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gidgup, M.J.R.; Kickett, M.; Hill, K.D.; Francis-Coad, J.; Weselman, T.; Coombes, J.; Ivers, R.; Bowser, N.; Palacios, V.; Hill, A.-M. Connecting and Reconnecting to a Community, with a Sense of Belonging—Exploring Aboriginal Elders’ Perspectives of Engaging in a Physical Activity Program. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2022, 33 (Suppl. S1), 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matenga-Ikihele, A.; McCool, J.; Dobson, R.; Fa’alau, F.; Whittaker, R. The Characteristics of Behaviour Change Interventions Used among Pacific People: A Systematic Search and Narrative Synthesis. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Patel, S.; Choy, C.; Zanowiak, J.; Rideout, C.; Yi, S.; Wyatt, L.; Taher, M.; Garcia-Dia, M.; Kim, S.; et al. Implementing Health Promotion Activities Using Community-Engaged Approaches in Asian American Faith-Based Organizations in New York City and New Jersey. Transl. Behav. Med. 2017, 7, 444–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palu, E.; MacMillan, D.F.; McBride, D.K.A.; Thomson, D.R.; Zarora, R.; Simmons, D. Effects of Lifestyle Interventions on Weight amongst Pasifika Communities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Reg. Health-West Pac. 2022, 25, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnicow, K.; Baranowski, T.; Ahluwalia, J.S.; Braithwaite, R.L. Cultural Sensitivity in Public Health: Defined and Demystified. Ethn. Dis. 1999, 9, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, G.; Bonilla, J.; Bellido, C. Ecological Validity and Cultural Sensitivity for Outcome Research: Issues for the Cultural Adaptation and Development of Psychosocial Treatments with Hispanics. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1995, 23, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tools|JBI. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Bender, M.S.; Cooper, B.A.; Flowers, E.; Ma, R.; Arai, S. Filipinos Fit and Trim—A Feasible and Efficacious DPP-Based Intervention Trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2018, 12, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, M.S.; Cooper, B.A.; Park, L.G.; Padash, S.; Arai, S. A Feasible and Efficacious Mobile-Phone Based Lifestyle Intervention for Filipino Americans with Type 2 Diabetes: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Diabetes 2017, 2, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhimla, A.; Power, K.; Sachs, M.; Bermudez, A.; Dinh, J.; San Juan, N.; Ma, G.X. Evaluating Psychosocial and Physical Activity Outcomes Following an Intervention among Filipino Americans. Health Promot. Perspect. 2021, 11, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirige, O.V.; Carlson, J.A.; Alcaraz, J.; Moy, K.L.; Rock, C.L.; Oades, R.; Sallis, J.F. Siglang Buhay: Nutrition and Physical Activity Promotion in Filipino-Americans Through Community Organizations. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2013, 19, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.; Braun, K.L.; Spinner, J.R.; Sturdevant, C.; Ancheta, S.J.; Yoshimura, S.R.; Compton, M.; Wang, J.-H.; Lee, C.J. Healthy Heart, Healthy Family: A NHLBI/HRSA Collaborative Employing Community Health Workers to Improve Heart Health. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2012, 23, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho-Lastimosa, I.; Chung-Do, J.J.; Hwang, P.W.; Radovich, T.; Rogerson, I.; Ho, K.; Keaulana, S.; Keawe‘aimoku Kaholokula, J.; Spencer, M.S. Integrating Native Hawaiian Tradition with the Modern Technology of Aquaponics. Glob. Health Promot. 2019, 26, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, J.; Matsuura, C.; Li, D.; Castro, R.; Leake, A. Lifestyle Intervention for Filipino Americans at Risk for Diabetes. J. Community Health Nurs. 2014, 31, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaholokula, J.K.; Mau, M.K.; Efird, J.T.; Leake, A.; West, M.; Palakiko, D.-M.; Yoshimura, S.R.; Kekauoha, B.P.; Rose, C.; Gomes, H. A Family and Community Focused Lifestyle Program Prevents Weight Regain in Pacific Islanders: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Health Educ. Behav. 2012, 39, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaholokula, J.K.; Wilson, R.E.; Townsend, C.K.M.; Zhang, G.X.; Chen, J.; Yoshimura, S.R.; Dillard, A.; Yokota, J.W.; Palakiko, D.M.; Gamiao, S.; et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program in Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Communities: The PILI ‘Ohana Project. Transl. Behav. Med. 2014, 4, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaholokula, J.K.; Look, M.; Mabellos, T.; Zhang, G.; de Silva, M.; Yoshimura, S.; Solatorio, C.; Wills, T.; Seto, T.B.; Sinclair, K.A. Cultural Dance Program Improves Hypertension Management for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders: A Pilot Randomized Trial. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2017, 4, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaholokula, J.K.; Look, M.A.; Wills, T.A.; de Silva, M.; Mabellos, T.; Seto, T.B.; Ahn, H.J.; Sinclair, K.A.; Buchwald, D. Kā-HOLO Project: A Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial of a Native Cultural Dance Program for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Native Hawaiians. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaholokula, J.K.; Look, M.; Mabellos, T.; Ahn, H.J.; Choi, S.Y.; Sinclair, K.A.; Wills, T.A.; Seto, T.B.; de Silva, M. A Cultural Dance Program Improves Hypertension Control and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Native Hawaiians: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Behav. Med. 2021, 55, 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaBreche, M.; Cheri, A.; Custodio, H.; Fex, C.C.; Foo, M.A.; Lepule, J.T.; May, V.T.; Orne, A.; Pang, J.K.; Pang, V.K.; et al. Let’s Move for Pacific Islander Communities: An Evidence-Based Intervention to Increase Physical Activity. J. Cancer Educ. 2016, 31, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leake, A.R.; Bermudo, V.C.; Jacob, J.; Jacob, M.R.; Inouye, J. Health Is Wealth: Methods to Improve Attendance in a Lifestyle Intervention for a Largely Immigrant Filipino-American Sample. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2012, 14, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.X.; Zhu, L.; Shive, S.E.; Zhang, G.; Senter, Y.R.; Topete, P.; Seals, B.; Zhai, S.; Wang, M.; Tan, Y. The Evaluation of IDEAL-REACH Program to Improve Nutrition among Asian American Community Members in the Philadelphia Metropolitan Area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.X.; Bhimla, A.; Zhu, L.; Beeber, M.; Aczon, F.; Tan, Y.; Quinn, S.B.; Khan, O.; Gadegbeku, C.A. Development of an Intervention to Promote Physical Activity and Reduce Dietary Sodium Intake for Preventing Hypertension and Chronic Disease in Filipino Americans. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2021, 8, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mau, M.K.; Glanz, K.; Severino, R.; Grove, J.S.; Johnson, B.; Curb, J.D. Mediators of Lifestyle Behavior Change in Native Hawaiians: Initial Findings from the Native Hawaiian Diabetes Intervention Program. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 1770–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mau, M.K.; Keawe’aimoku Kaholokula, J.; West, M.R.; Leake, A.; Efird, J.T.; Rose, C.; Palakiko, D.-M.; Yoshimura, S.; Kekauoha, P.B.; Gomes, H. Translating Diabetes Prevention into Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Communities: The PILI ’Ohana Pilot Project. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2010, 4, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, R.; Chen, C.; Williams, A.E.; Albright, C.L.; Nigg, C.R.; Oshiro, C.E.; Stevens, V.J. US Acculturation Is Associated with Health Behaviors and Obesity, but Not Their Change, with a Hotel-Based Intervention among Asian-Pacific Islanders. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Railey, A.F.; Muller, C.; Noonan, C.; Schmitter-Edgecombe, M.; Sinclair, K.; Kim, C.; Look, M.; Kaholokula, J.K. Cost Effectiveness of a Cultural Physical Activity Intervention to Reduce Blood Pressure Among Native Hawaiians with Hypertension. PharmacoEconomics-Open 2022, 6, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, K.A.; Thompson, C.; Makahi, E.K.; Shea-Solatorio, C.; Yoshimura, S.R.; Townsend, C.K.M.; Kaholokula, J.K. Outcomes from a Diabetes Self-Management Intervention for Native Hawaiians and Pacific People: Partners in Care. Ann. Behav. Med. Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2013, 45, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomioka, M.; Braun, K.L.; Cook, V.A.; Compton, M.; Wertin, K. Improving Behavioral and Clinical Indicators in Asians and Pacific Islanders with Diabetes: Findings from a Community Clinic-Based Program. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 104, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursua, R.A.; Aguilar, D.E.; Wyatt, L.C.; Katigbak, C.; Islam, N.S.; Tandon, S.D.; Nur, P.R.M.Q.; Van Devanter, N.; Rey, M.J.; Trinh-Shevrin, C. A Community Health Worker Intervention to Improve Management of Hypertension among Filipino Americans in New York and New Jersey: A Pilot Study. Ethn. Dis. 2014, 24, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yi, S.S.; Wyatt, L.C.; Patel, S.; Choy, C.; Dhar, R.; Zanowiak, J.M.; Chuhan, H.; Taher, M.D.; Garcia, M.; Kavathe, R.; et al. A Faith-Based Intervention to Reduce Blood Pressure in Underserved Metropolitan New York Immigrant Communities. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2019, 16, E106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhimla, A.; Razon, S.; Ma, G.; Salvatore, G.; Trout, J.; Sachs, M. A Feasibility Study Assessing a Culturally Relevant Physical Activity Intervention for Midlife Filipino Women. J. Phys. Act. Res. 2018, 3, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijangga, M.O.; Pack, D.V.; Yokota, N.O.; Vien, M.H.; Dryland, A.D.G.; Ivey, S.L. Culturally-Tailored Cookbook for Promoting Positive Dietary Change among Hypertensive Filipino Americans: A Pilot Study. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1114919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.; Yu, F.; Park, L.G.; Fukuoka, Y.; Wong, C.; Gildengorin, G.; Nguyen, T.T.; Tsoh, J.Y.; Jih, J. An App-Based Physical Activity Intervention in Community-Dwelling Chinese-, Tagalog-, and Vietnamese-Speaking Americans: Single-Arm Intervention Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e56373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas 2025; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2018–2022: Guam; World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific: Metro Manila, Philippines, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Jin, C.; Zhang, J.; Sun, H.; Ma, B.; Yang, X.; Liu, T.; Yang, K.; Li, Y. Diabetes Burden, Trends, and Inequalities in Western Pacific Region, 1990–2019: A Population-Based Study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2023, 17, 102852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.C.N.; Cho, N.H.; Tajima, N.; Shaw, J. Diabetes in the Western Pacific Region—Past, Present and Future. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 103, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curriculum for the National DPP Lifestyle Change Program. National DPP Cover. Toolkit. Available online: https://coveragetoolkit.org/national-dpp-curriculum/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- McElfish, P.A.; Purvis, R.S.; Esquivel, M.K.; Sinclair, K.A.; Townsend, C.; Hawley, N.L.; Haggard-Duff, L.K.; Keawe’aimoku Kaholokula, J. Diabetes Disparities and Promising Interventions to Address Diabetes in Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Populations. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2019, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Form Cancer and Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. Available online: https://www.apiahf.org/resource/cancer-fact-sheet-for-aanhpi-communities (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Rhee, C.M.; You, A.S.; Page, V.; Hayashida, G.; Kataoka-Yahiro, M.; Davis, J.; Wong, L.L.; Narasaki, Y.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Chronic Kidney Disease and Its Risk Factors Among Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders in Hawaii. Nephron 2023, 147, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hixson, L.; Hepler, B.; Ouk Kim, M. The Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander Population: 2010. 2012. Available online: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2012/dec/c2010br-12.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- 2010 Census Dashboards|The Bureau of Statistics and Plans Guam. Available online: https://bsp.guam.gov/2010-census-dashboards/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Delavari, M.; Sønderlund, A.L.; Swinburn, B.; Mellor, D.; Renzaho, A. Acculturation and Obesity among Migrant Populations in High Income Countries—A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, C.; Mirchandani, G.G.; Castrucci, B.C.; Chávez, N.; Handler, A.; Hoelscher, D.M. The Effects of Acculturation on Healthy Lifestyle Characteristics among Hispanic Fourth-Grade Children in Texas Public Schools, 2004–2005. J. Sch. Health 2012, 82, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aflague, T.F.; Hammond, K.; Delos Reyes, B.; Rios, D.; De Leon, E.; Leon Guerrero, R.T.; Esquivel, M.K. Barriers, Facilitators, and Strategies for Developing a Culturally Informed Lifestyle Intervention for Native Hawaiian, CHamoru, and Filipino Breast Cancer Survivors: Mixed-Methods Findings from Focus Group Participants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aflague, T.F.; Esquivel, M.K.; Hammond, K.; Delos Reyes, B.; Kaholokula, J.K. Traditional and New Lifestyle Interventions to Prevent Breast Cancer Recurrence (TANICA): A Qualitative Study. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| PubMed | Search 1: (intervention AND (“diet” OR “nutrition” OR “physical activity” OR “exercise” OR “lifestyle”)) AND cultur* AND Filipin* Search 2: (intervention AND (“diet” OR “nutrition” OR “physical activity” OR “exercise” OR “lifestyle”)) AND cultur* AND (CHamor* OR “Guam”) Search 3: (intervention AND (“diet” OR “nutrition” OR “physical activity” OR “exercise” OR “lifestyle”)) AND cultur* AND “Native Hawaiian” |

| ProQuest | Search 1: noft(“intervention” AND (“diet” OR “nutrition” OR “physical activity” OR “exercise” OR “lifestyle”)) AND cultur* AND Filipin* Search 2: noft(“intervention” AND (“diet” OR “nutrition” OR “physical activity” OR “exercise” OR “lifestyle”)) AND cultur* AND (CHamor* OR “Guam”) Search 3: noft(“intervention” AND (“diet” OR “nutrition” OR “physical activity” OR “exercise” OR “lifestyle”)) AND cultur* AND “Native Hawaiian” To narrow search: used noft = no full text |

| EBSCO (CINAHL, Academic Search Complete, and Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition) | Search 1: (intervention AND (“diet” OR “nutrition” OR “physical activity” OR “exercise” OR “lifestyle”)) AND cultur* AND Filipin* Search 2: (intervention AND (“diet” OR “nutrition” OR “physical activity” OR “exercise” OR “lifestyle”)) AND cultur* AND (CHamor* OR “Guam”) Search 3: (intervention AND (“diet” OR “nutrition” OR “physical activity” OR “exercise” OR “lifestyle”)) AND cultur* AND “Native Hawaiian” |

| Included Studies Author Name (Publication Year) | Focus | Program Type | Ethnic Group Included | Location | Social Ecological Model (SEM) | Cultural Sensitivity Elements | Cultural Adaptation | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Condition 1 | Nutrition | Physical Activity | Other lifestyle | Native Hawaiian | Filipino | CHamoru | Pacific Islander, Undefined | Hawaiʻi | California | East Coast | Individual | Interpersonal | Community | Organizational | Policy | Language | Persons | Metaphor | Content | Concepts | Goals | Methods | Context | Deep | Surface | |

| Bender et al. (2017) [40] | DM, CVD | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||

| Bender et al. (2018) [39] | OB, Pre-DM | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||

| Bhimla et al. (2018) [63] | CD | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||||

| Bhimla et al. (2021) [41] | CD | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||

| Dirige et al. (2013) [42] | HP | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||

| Fernandes et al. (2012) [43] | CVD | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||

| Ho-Lastimosa et al. (2019) [44] | HP | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||

| Inouye et al. (2014) [45] | Pre-DM | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||

| Kaholokula et al. (2012) [46] | OB | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||

| Kaholokula et al. (2014) [47] | Pre-DM | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||

| Kaholokula, Look, Mabellos et al. (2017) [48] | HTN | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||

| Kaholokula, Look, Wills et al. (2017) [49] | CVD | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||

| Kaholokula et al. (2021) [50] | HT, CVD | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||

| Kwon et al. (2017) [32] | HP, HTN | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||

| LaBreche et al. (2016) [51] | HP, OB | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||

| Leake et al. (2012) [52] | Pre-DM | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||

| Ma et al. (2019) [53] | HP, Pre-DM, Pre-CVD, Pre-HTN | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||||||

| Ma et al. (2021) [54] | Pre-HTN | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||||||

| Maglalang et al. (2017) [8] | DM | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||

| Mau et al. (2001) [55] | Pre-DM | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||||||||

| Mau et al. (2010) [56] | OB, Pre-DM | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||

| Nguyen et al. (2024) [65] | HP | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||||||||

| Novotny et al. (2012) [57] | OB | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||||||

| Railey et al. (2022) [58] | HTN | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||

| Sijangga et al. (2023) [64] | HTN | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||||

| Sinclair et al. (2013) [59] | DM | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||

| Tomioka et al. (2014) [60] | DM | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||||

| Ursua et al. (2014) [61] | HTN | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||||

| Yi et al. (2019) [62] | HTN | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||

| Total | - | 20 | 25 | 12 | 13 | 22 | 2 | 8 | 15 | 7 | 7 | 29 | 24 | 18 | 7 | 1 | 24 | 28 | 12 | 27 | 23 | 20 | 25 | 22 | 20 | 28 |

| Included Studies’ Author Name (Publication Year) | Nutrition Cultural Adaptation | Physical Activity Cultural Adaptation | Language Adaptation | Sociocultural and Community-Engaged Components |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bender et al. (2017) [40] | Photos of common Filipino foods were used in Filipino food pamphlets. Healthy Filipino food alternatives and recipes shared. | Educational materials tailored for Filipino cultural values and beliefs related to physical activity. Culturally relevant activities, such as Zumba®, cha cha, basketball, and walking. | Healthy lifestyle education pamphlets translated in Tagalog for Filipino Americans. | Family members were welcome to attend in-office visits. Community stakeholders informed the study design and trained community health workers from Filipino communities to deliver the programs. Informed by past studies among Filipinos. |

| Bender et al. (2018) [39] | Photos of common Filipino foods were used in Filipino food pamphlets, with healthier options as substitutes for commonly eaten unhealthy Filipino foods and drinks. | Photos of Filipino family members exercising and walking together outside and Filipino activities—walking, dancing, Zumba®, basketball, and bowling. Indoor options to limit sun exposure. | English and Tagalog utilized to deliver lessons. | Family members were welcome to attend in-office visits. Filipino community health workers trained to deliver program. |

| Bhimla et al. (2018) [63] | None. | Zumba® held at a Filipino community center and local church near participants’ homes. | Bilingual Filipino instructors. | Informed by community leaders and female community members. Filipino community health workers were trained to deliver program. Group fitness classes were designed to enhance collectivism. |

| Bhimla et al. (2021) [41] | None. | Culturally relevant physical activity classes: Zumba®, line dance, Hip Hop, and strength training in a group setting. | Facilitators spoke two Filipino dialects. English and Tagalog were utilized to deliver lessons. | Informed by past research on preferred activities for this population. Recruitment involved Catholic churches frequented by Filipino families. Family- and community-oriented. Filipino community health workers were trained to deliver program. |

| Dirige et al. (2013) [42] | Hands-on activities. | Group activities (e.g., aerobic classes, kickboxing, dancing, gardening, and basketball tournaments). | Surveys were available in Tagalog and administered by bilingual staff. | Program was conducted through Filipino social clubs (i.e., Filipino–American social clubs in San Diego, CA, USA). |

| Fernandes et al. (2012) [43] | Culturally tailored curriculum lessons. | Community gardening and chair aerobics. | Nutrition booklets were provided in Tagalog. Community health workers spoke Tagalog. | Recruitment from a Filipino neighborhood. Community health workers were experienced in working with this community, led physical activities, and planned monthly celebrations with families. |

| Ho-Lastimosa et al. (2019) [44] | Use of Hawaiian cultural practices and food sovereignty; la’au lapa’au (Native traditional healing through plants and spirituality); ’ai pono (nourishing foods); and cultural value of ’aina (land) and malama ’aina (taking care of the land). | Gardening (i.e., planting, growing, and harvesting plants). | Incorporation of olelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language) into program materials. | Built on previous community grassroots efforts related to backyard aquaponics. Workshops that used a hands-on family-based collective learning approach, which aligns with Native Hawaiian educational pedagogy, took place in a Native Hawaiian community place. Native Hawaiian cultural practices emphasized. |

| Inouye et al. (2014) [45] | Not described in detail. | Not described in detail. | Facilitators fluent in English and two Filipino dialects. | Recruitment from Catholic churches frequented by Filipino families. Filipino health care workers served as small group leaders. Family invited to small group sessions. Philippine Nurses Association members served as the advisory committee during the curriculum design, recruitment, and evaluation. |

| Kaholokula et al. (2012) [46] | Family meal planning exercise. | Family physical activity planning. Scheduling of free time for family activities. | Sessions delivered in a native language by a bilingual community healthcare and peer educator. | Strategies for each session were identified by community assessments and input from community investigators. Sessions incorporated family and cultural community activities. |

| Kaholokula et al. (2014) [47] | Locally relavant food sources. | None. | Program delivered in language native to the Chuukese group. | Informed by community assessments among Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. Lessons were delivered in group settings to emphasize the cultural value of ’ohana (i.e., the preference for working together and group decision making). Lessons were made practical for the socioeconomic realities of many Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. |

| Kaholokula, Look, Mabellos et al. (2017) [48] | Cooking demonstrations of healthy recipes of relavant ethnic foods. | Hula, Native Hawaiian cultural dance utilized and led by kumu hula (hula expert). | Olelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language) was utilized during lessons. | Community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach informed study. Involved Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander community investigators. |

| Kaholokula, Look, Wills et al. (2017) [49] | None. | Hula, Native Hawaiian cultural dance. | Olelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language) was utilized during lessons. | Community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach informed study. Classes led by kumu hula (hula expert) and relevant peer educators. |

| Kaholokula et al. (2021) [50]. | None. | Hula, Native Hawaiian cultural dance utilized and led by kumu hula (hula expert). | Olelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language) was utilized during lessons. | Community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach informed study. Involved Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander community investigators. |

| Kwon et al. (2017) [32] | Nutrition outreach materials tailored to address Asian condiments and sources of sodium. Incorporated fruits and vegetables such as bitter melon, cabbage, guava, starfruit, or healthy traditional foods/modifications in program materials. | None. | Surveys were translated (i.e., into Tagalog) and administered by bilingual staff. | Program guided by Filipino communities and local health departments. Pastors were enrolled in study and disseminated project info through faith-based wide announcements in Filipino churches. |

| LaBreche et al. (2016) [51] | None. | Physical activity video incorporating movements, cultural elements, people, and music from Pacific Islands and collaboration with a Pacific Islander (PI) filmmaker. | National Cancer Institute cancer prevention posters translated into Pacific Islander languages, such as Chamoru, Fijian, Marshallese, Samoan, and Tongan. | Program delivered by community leaders and focused on Pacific Islander social, cultural, and faith-based organizations. |

| Leake et al. (2012) [52] | Filipino cultural foods. | Filipino cultural activities. | Bilingual facilitator. Curriculum was presented in English interspersed with Tagalog. Filipino proverbs were incorporated into lessons. | Facilitated by a community member (Filipino leader). Delivered in an area frequented by Filipino–American families, also located near two churches. Scheduling accounted for family, social, and work obligations. |

| Ma et al. (2019) [53] | Nutrition messages included cultural foods and Asian food markets. | None. | Bilingual translators. Education materials were in English and Asian ethnic languages (Filipino). | Communication via Asian newspapers and media outlets. Technical assistance provided to community-based organizational support staff. |

| Ma et al. (2021) [54] | None. | Culturally appropriate physical activity sessions | None. | Sessions were led by Filipino community health educators. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) framework was used to guide the development of the study program. |

| Maglalang et al. (2017) [8] | Photos of common Filipino foods were used in Filipino food pamphlets. Healthy Filipino food alternatives and recipes shared. | Culturally relevant activities, such as Zumba®, cha cha, basketball, and walking. Relapse prevention for Filipino American sedentary cultural practices (e.g., extended Mahjong playing time). | Healthy lifestyle education pamphlets translated in Tagalog for Filipino Americans. | Family members were welcome at in-office visits. Community stakeholders informed study design and trained community health workers from Filipino communities to deliver the programs. Informed by past studies among Filipinos. |

| Mau et al. (2001) [55] | None. | None. | Incorporation of olelo Hawaiʻi (Native Hawaiian language) into program (example: ʻohana for family). | Culturally responsive lifestyle program was developed and implemented by trained community peer educators. |

| Mau et al. (2010) [56] | Local food examples and common nutrition and diet-related behaviors. | Group-based classes, in line with a collectivist cultural value. | The focus groups were conducted in a language native to Chuukese, Filipino, and Samoan groups. Lessons were in “plain language”, with cultural/linguistic relevance to Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. | Program was designed using community-based participatory research (CBPR). Program was delivered by peer educators. Social support issues related to cultural practices were addressed. |

| Nguyen et al. (2024) [65] | None. | App had visuals adapted to the preferred cutural context and delivered messages in a tone and format familiar to each group. | Program was adapted for Chinese, Tagalog, and Vietnamese speakers. All program materials were translated, followed by critical reviews of cultural and language equivalence at a 4th-grade reading level by culturally and linguistically competent staff. | Worked with trusted ethnic community organizations. Staff were bicultural. |

| Novotny et al. (2012) [57] | Ethnic foods commonly consumed by the general population in Hawaiʻi were emphasized. | Physical activities appropriate for the local environment were incorporated. Group-based classes were designed. | Surveys were available in English, Chinese, and Korean. | Program was designed around the broad patterns of culture found in Hawaiʻi due to multiethnic participants. |

| Railey et al. (2022) [58] | None. | Hula—traditional Hawaiian dance. | None. | Programs were delivered by community members (Kumu hula, or hula expert, and peer educators). Community-based organizations were involved in the study design and interpretation of findings. |

| Sijangga et al. (2023) [64] | Traditional Filipino recipes were adapted to be low sodium, fat, and cholersterol while maintaining traditional flavors; use of Filipino ingredients, cookbook created with Filipino chefs, story telling framework in cookbook. | None. | Tagalog was used in the title of the cookbook. | Cultural practice of shared meals with family and friends. Carefully selected individuals (Filipino American culinary experts) were chosen to contribute to cookbook recipes. |

| Sinclair et al. (2013) [59] | Images of Hawaiʻi and local foods. | Images of physical activity relevant to Hawaiian environment were included. | “Local” language and examples were used to convey some educational content. | Community leaders and health advocates from four distinct community organizations serving Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. Program theory included cultural symbols and themes, cultural patterns and concepts, values, norms, and relationships. Group-based educational format was used to facilitate social support. Storytelling utilized locally relevant examples of personal experiences with diabetes. |

| Tomioka et al. (2014) [60]. | None. | None. | Bilingual trained staff who took time during and after each session to reinforce key messages in participants’ native languages. | Recruitment was held at community events, such as health fairs and word-of-mouth recruitments from previous participants. Pre-workshop orientation by program leaders and a community physician. Involved family members at a graduation party, 6-month “reunion”, and follow up. |

| Ursua et al. (2014) [61] | Food examples represented foods availabile within the community, | Exercise examples represented activities availabile within the community. | Program was delivered by bilingual Filipino community health workers. | Curriculum was culturally designed for Filipino American community through community-engaged process. Programs held at the local library, community centers, apartment buildings, and the lead community partner’s office. Incoporated Filipino history and culture and health and social services and health insurance options. |

| Yi et al. (2019) [62] | Culturally tailored lifestyle counseling on weight management; examples of healthy plates using common cultural foods. | None. | Surveys were translated (i.e., into Tagalog) and administered by bilingual staff. | Trained faith-based leaders implemented the culturally adapted program for four Asian American communities. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esquivel, M.K.; Hammond, K.; Delos Reyes, B.C.; Rios, D.C.; Mian, N.; de Leon, E.C.; Torres, S.M.; Aflague, T.F. Part 1: A Systematic Review to Describe Existing Cultural Adaptations in Lifestyle, Nutrition, and Physical Activity Programs for Native Hawaiian, CHamoru, and Filipino Populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111673

Esquivel MK, Hammond K, Delos Reyes BC, Rios DC, Mian N, de Leon EC, Torres SM, Aflague TF. Part 1: A Systematic Review to Describe Existing Cultural Adaptations in Lifestyle, Nutrition, and Physical Activity Programs for Native Hawaiian, CHamoru, and Filipino Populations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111673

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsquivel, Monica K., Kristi Hammond, Bernice C. Delos Reyes, Dareon C. Rios, Niza Mian, Elaine C. de Leon, Samantha M. Torres, and Tanisha Franquez Aflague. 2025. "Part 1: A Systematic Review to Describe Existing Cultural Adaptations in Lifestyle, Nutrition, and Physical Activity Programs for Native Hawaiian, CHamoru, and Filipino Populations" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111673

APA StyleEsquivel, M. K., Hammond, K., Delos Reyes, B. C., Rios, D. C., Mian, N., de Leon, E. C., Torres, S. M., & Aflague, T. F. (2025). Part 1: A Systematic Review to Describe Existing Cultural Adaptations in Lifestyle, Nutrition, and Physical Activity Programs for Native Hawaiian, CHamoru, and Filipino Populations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111673