The Housing Instability Scale: Determining a Cutoff Score and Its Utility for Contextualizing Health Outcomes in People Who Use Drugs

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Survey Development

2.3. Measure: The Housing Instability Scale

- Lived in an undesired or unstable housing situation in the past 6 months;

- Uncertainty about maintaining current housing for the next 6 months;

- Stayed with family or friends to avoid homelessness;

- Experienced difficulty paying for housing (e.g., rent or mortgage);

- Faced challenges obtaining stable housing;

- Low confidence in ability to pay for housing this month;

- Experienced frequent moving (3 or more times) in the past 6 months.

2.4. Data Management

2.5. Data Analysis

- Crude models included housing stability as the sole predictor.

- Adjustment models controlled for relevant confounders such as SSP use, employment status, and use of specific drug classes (example: opioids, amphetamines).

- Model results were presented as Odds Ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), along with corresponding p-values. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

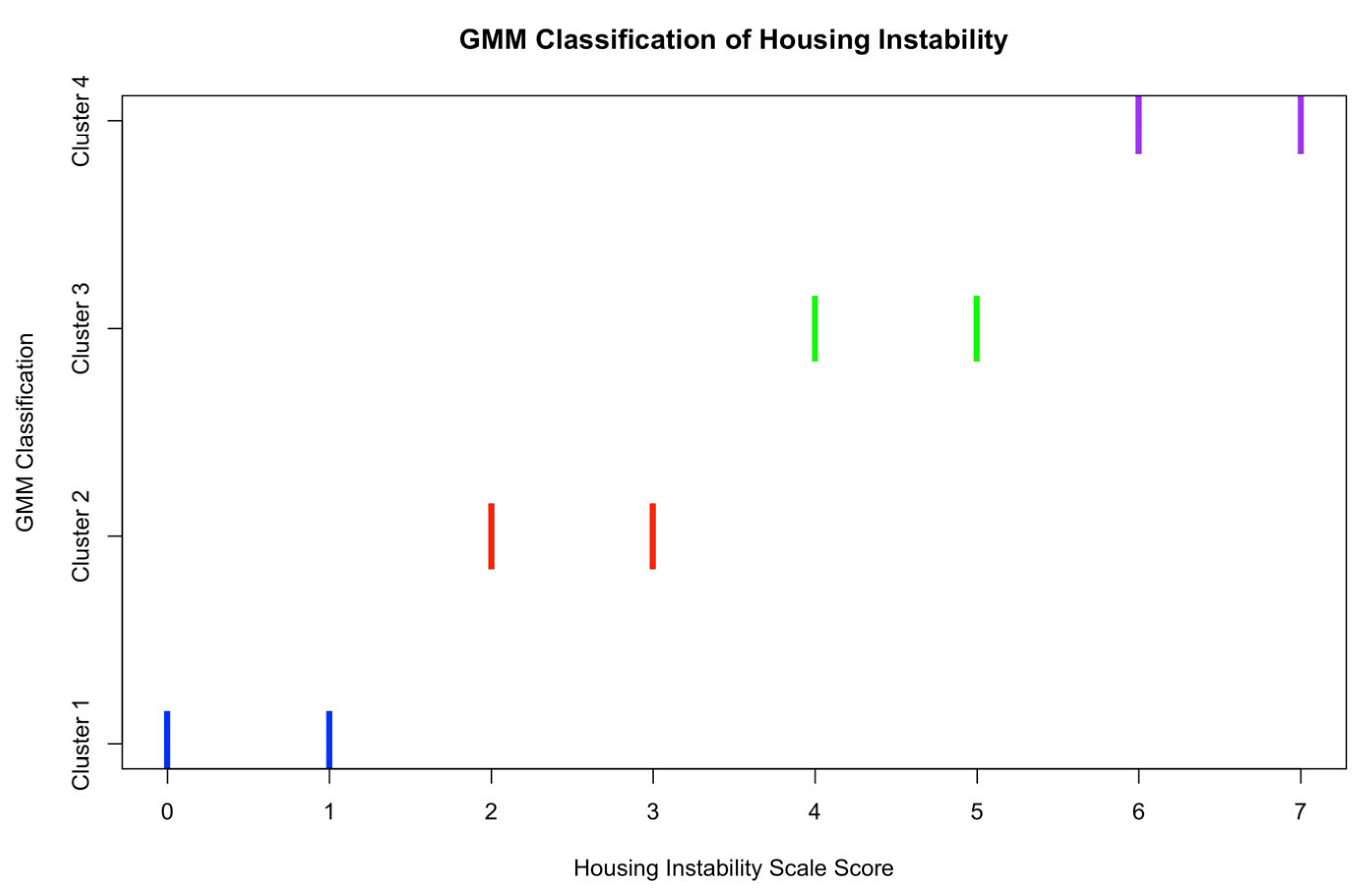

Cutoff Determination

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

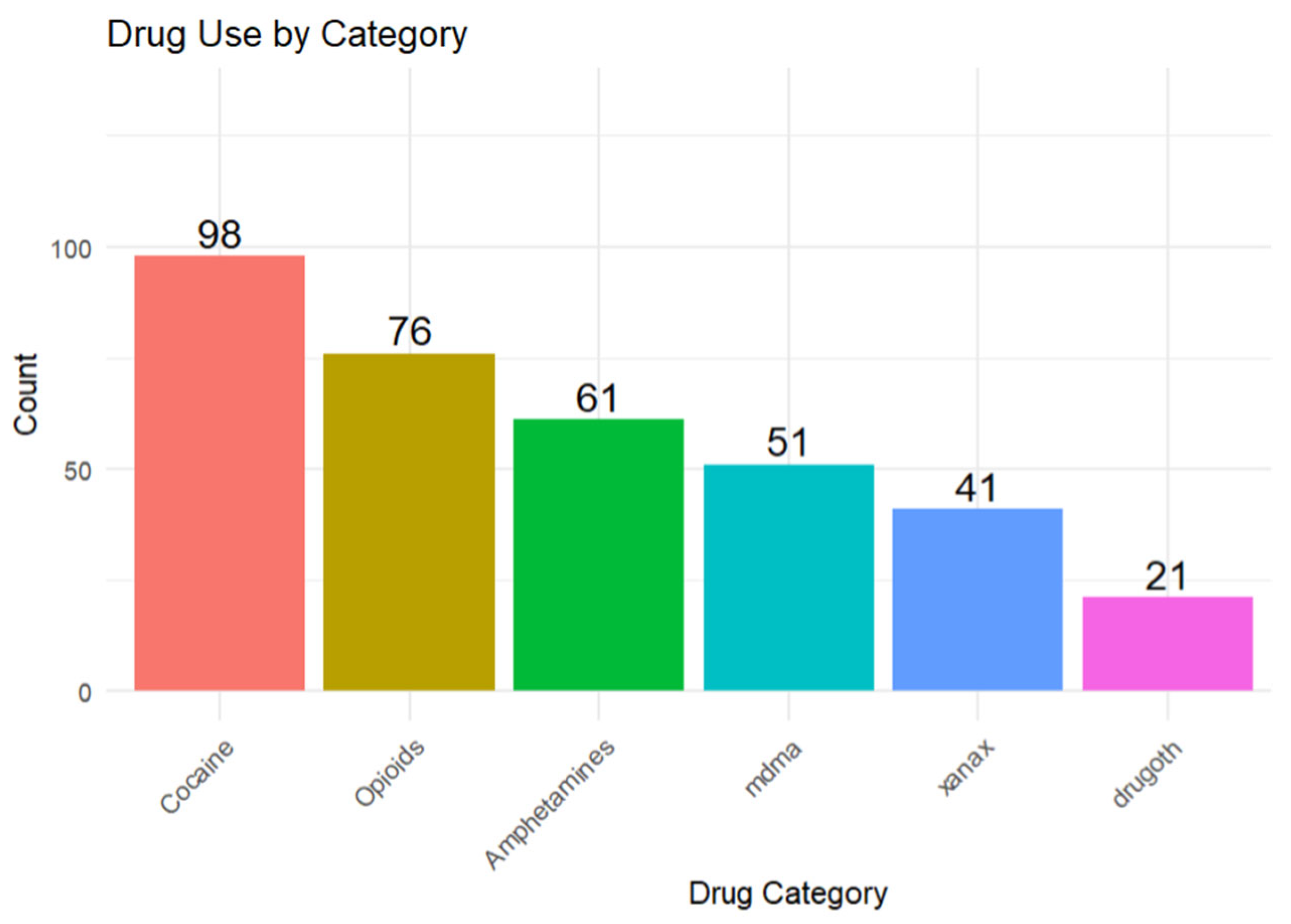

3.2. Reported Drug Use

3.3. Housing Stability and Health Outcomes

3.4. Adverse Health Outcomes Results

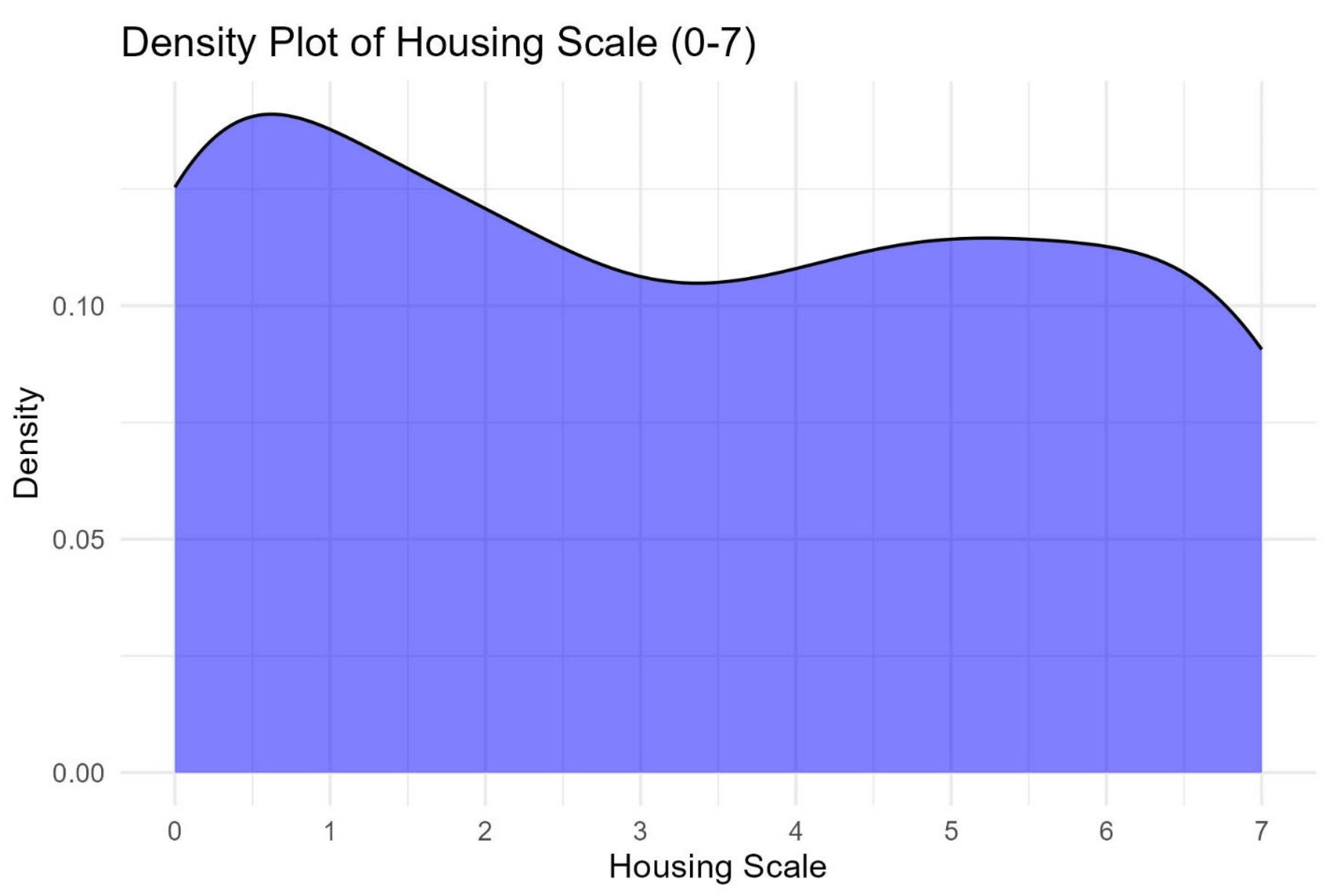

3.5. Housing Instability Scale Cut-Off

4. Discussion

4.1. Housing Instability and Health Outcomes

4.1.1. Role of SSP Use

4.1.2. Substance Use as a Confounder

4.1.3. Housing Instability Scale Cut-Off

4.1.4. Public Health Impact

4.1.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| United States | US |

| PWID | People who inject drugs |

| PWUD | People Who Use Drugs |

| SSP | Syringe Services Program |

| HIS | Housing Instability Scale |

| AOR | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| MD | Doctor of Medicine |

| PhD | Doctor of Philosophy |

| GED | General Educational Development |

| R | R Programming Language (Statistical Computing), Version 4.3.3 was used for this analysis. |

| GMM | Gaussian Mixture Modeling |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| MPlus | MPlus Statistical Software |

| mclust | Model-based Clustering Package in R Version 4.3.3 |

| HCV | Hepatitis C Virus |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

Appendix A

| Number of Components (G) | E | V |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | −696.59 | −696.59 |

| 2 | −669.51 | −672.19 |

| 3 | −668.72 | NA |

| 4 | −659.09 | NA |

| 5 | −669.33 | NA |

| 6 | −672.18 | NA |

| 7 | −632.07 | NA |

References

- Goldshear, J.L.; Corsi, K.F.; Ceasar, R.C.; Ganesh, S.S.; Simpson, K.A.; Kral, A.H.; Bluthenthal, R.N. Housing and Displacement as Risk Factors for Negative Health Outcomes Among People Who Inject Drugs in Los Angeles, CA, and Denver, CO, USA. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meckstroth, J.A. Ancillary Services to Support Welfare to Work; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arum, C.; Fraser, H.; Artenie, A.A.; Bivegete, S.; Trickey, A.; Alary, M.; Astemborski, J.; Iversen, J.; Lim, A.G.; MacGregor, L.; et al. Homelessness, unstable housing, and risk of HIV and hepatitis C virus acquisition among people who inject drugs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e309–e323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, D.R.; Dickins, K.A.; Adams, L.D.; Nueces, D.D.L.; Weinstock, K.; Wright, J.; Gaeta, J.M.; Baggett, T.P. Drug Overdose Mortality Among People Experiencing Homelessness, 2003 to 2018. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2142676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, E.M.; Strenth, C.R.; Hedrick, L.P.; Paterson, R.C.; Curiel, J.; Joseph, A.E.; Brown, T.W.; Kimball, J.N. Medical Comorbidities and Medication Use Among Homeless Adults Seeking Mental Health Treatment. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldridge, R.W.; Story, A.; Hwang, S.W.; Nordentoft, M.; Luchenski, S.A.; Hartwell, G.; Tweed, E.J.; Lewer, D.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Hayward, A.C. Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet 2018, 391, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Housing Instability: Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/housing-instability (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. State of Homelessness: 2023 Edition. Available online: https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/homelessness-statistics/state-of-homelessness/ (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Sims, M.; Kershaw, K.N.; Breathett, K.; Jackson, E.A.; Lewis, L.M.; Mujahid, M.S.; Suglia, S.F. Importance of Housing and Cardiovascular Health and Well-Being: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2020, 13, e000089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehrung, R.; Hu, D.; Guo, Y.; Zheng, K.; Chen, Y. Investigating the effects of housing instability on depression, anxiety, and mental health treatment in childhood and adolescence. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.06011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aadell, C.J.; Saldana, C.S.; Schoonveld, M.M.; Meehan, A.A.; Lin, C.K.; Butler, J.C.; Mosites, E. Infectious Diseases Among People Experiencing Homelessness: A Systematic Review of the Literature in the United States and Canada, 2003–2022. Public Health Rep. 2024, 139, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swope, C.B.; Hernández, D. Housing as a determinant of health equity: A conceptual model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 243, 112571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J. Lifetime and 1-year prevalence of homelessness in the US population: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. J. Public Health 2018, 40, 65–74, Erratum in J. Public Health 2017, 39, 879–880. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdx099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Coalition for the Homeless. Substance Use and Homelessness; Bringing America Home: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, G.T.; Seth, P.; Noonan, R.K. Continued Increases in Overdose Deaths Related to Synthetic Opioids: Implications for Clinical Practice. JAMA 2021, 325, 1151–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, K.M.; Fockele, C.E.; Maguire, M. Overdose and Homelessness-Why We Need to Talk About Housing. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 5, e2142685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, R.; D’Amico, E.J.; Klein, D.J.; Rodriguez, A.; Pedersen, E.R.; Tucker, J.S. In Flux: Associations of Substance Use with Instability in Housing, Employment, and Income Among Young Adults Experiencing Homelessness. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compton, P. The United States opioid crisis: Big pharma alone is not to blame. Prev. Med. 2023, 177, 107777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, L.; Amy Peacock, P.; Colledge, S.; Leung, J.; Grebely, J.; Vickerman, P.; Stone, J.; Cunningham, E.B.; Trickey, A.; Dumchev, K.; et al. Global Prevalence of Injecting Drug Use and Sociodemographic Characteristics and Prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people Who Inject Drugs: A Multistage Systematic Review. Lancet Glob. Health 2017, 5, e1192–e1207, Erratum in Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30446-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, J.; Artenie, A.; Hickman, M.; Martin, N.K.; Degenhardt, L.; Fraser, H.; Vickerman, P. The Contribution of Unstable Housing to HIV and Hepatitis C Virus Transmission Among People Who Inject Drugs Globally, Regionally, and at Country Level: A Modelling Study. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e136–e145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farero, A.; Sullivan, C.M.; López-Zerón, G.; Bowles, R.P.; Sprecher, M.; Chiaramonte, D.; Engleton, J. Development and Validation of The Housing Instability Scale. J. Soc. Distress Homeless 2024, 33, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, C.; Reinschmidt, R.S.; Chow, L. Sense of belonging in a majority-minority Hispanic Serving Institution. J. Latinos Educ. 2024, 24, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, C.M.; Simmons, C.; Guerrero, M.; Farero, A.; López-Zerón, G.; Ayeni, O.O.; Chiaramonte, D.; Sprecher, M.; Fernandez, A.I. Domestic Violence Housing First Model and Association With Survivors’ Housing Stability, Safety, and Well-being Over 2 Years. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2320213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman-Williams, R.; Simmons, C.; Chiaramonte, D.; Ayeni, O.O.; Guerrero, M.; Sprecher, M.; Sullivan, C.M. Domestic violence survivors’ Housing Stability, safety, and Well-Being Over Time: Examining the Role of Domestic Violence Housing First, Social Support, and Material Hardship. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2023, 93, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, A.; Piccione, C.; Fisher, A.; Matt, K.; Adreini, M.; Bingham, D. Survey Development: Community Involvement in the Design and Implementation Process. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2019, 25 (Suppl. S5), S77–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.D.; Klipp, S.P.; Leon, K.; Liebschutz, J.M.; Merlin, J.; Murray-Krezan, C.; Nolette, S.; Phillips, K.T.; Stein, M.; Weinstock, N.; et al. “To Not Feel Fake, It Can’t Be Fake”: Co-Creation of a Harm Reduction, Peer-Delivered, Health-System Intervention for People Who Use Drugs. Harm Reduct. J. 2025, 22 (Suppl. S1), 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, H.; Byard, J.; Elswick, A.; Fallin-Bennett, A. The Co-Creation and Evaluation of a Recovery Community Center Bundled Model to Build Recovery Capital through the Promotion of Reproductive Health and Justice. Addict. Res. Theory 2024, 32, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maghsoudi, N.; Tanguay, J.; Scarfone, K.; Rammohan, I.; Ziegler, C.; Werb, D.; Scheim, A.I. Drug checking services for people who use drugs: A systematic review. Addiction 2022, 117, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliot, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R (Version 2023.09.1); Posit Software, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: http://posit.co/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Francois, R.; Henry, L.; Muller, K.; Vaughan, D. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation (Version 1.1.4). 2023. Available online: https://dplyr.tidyverse.org (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Wickham, K.; Francois, R.; Henry, L.; Muller, K. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Wei, T.; Simko, V. coorplot: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix (Version 0.95). 2024. Available online: https://github.com/taiyun/corrplot (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Schloerke, B.; Crowley, J.; Cook, D.; Hofmann, H.; Wickham, H.; Briatte, F.; Marbach, M.; Gleason, K. GGally: Extension to ‘ggplot2’ (Version 2.2.1). 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/GGally/index.html (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Girlich, M. tidyr: Tidy Messy Data (Version 1.3.1). 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tidyr (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Revelle, W. psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research (Version 2.4.2); Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 2024; Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Hester, J.; Bryan, J. readr: Read Rectangular Text Data (Version 2.1.4). 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=readr (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Ludecke, D. sjPlot: Data Visualization for Statistics in Social Science (Version 2.8.14). 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sjPlot (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Yoshida, K.; Bohn, J.; Schuster, T. tableone: Create ‘Table 1’ to Describe Baseline Characteristics (Version 0.13.2). 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tableone (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Gohel, D. flextable: Functions for Tabular Reporting (Version 0.0.5). 2024. Available online: https://github.com/davidgohel/flextable/blob/master/R/flextable-package.R (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Gohel, D. Officer: Manipulation of Microsoft Word and PowerPoint Documents (Version 0.6.6). 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=officer (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Scrucca, L.; Fraley, C.; Murphy, T.B.; Raftery, A.E. Model-Based Clustering, Classification, and Density Estimation Using Mclust in R.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1032234953. Available online: https://mclust-org.github.io/book/ (accessed on 11 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, J.; Hassan, M.; Zhang, T.; Yang, C.; Zhou, X.; Jia, F. Density Peak Clustering Algorithms: A Review on the Decade 2014–2023. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, K.; Williams, L.D.; Kaplan, C.; Pineros, J.; Lee, E.; Kaufmann, M.; Mackesy-Amiti, M.E.; Boodram, B. A Novel Index Measure of Housing-Related Risk as a Predictor of Overdose Among Young People Who Inject Drugs and Injection Networks. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, A.M.; Kesich, Z.; Crane, H.M.; Feinberg, J.; Friedmann, P.D.; Go, V.F.; Jenkins, W.D.; Korthuis, P.; Miller, W.C.; Pho, M.T.; et al. Rural Houselessness Among People Who Use Drugs in the United States: Results from the National Rural Opioid Initiative. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2025, 266, 112498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, J.C.; Bluthenthal, R.N.; Wenger, L.D.; Auerswald, C.L.; Henwood, B.F.; Kral, A.H. Health Risk Associated with Residential Relocation Among People Who Inject Drugs in Los Angeles and San Francisco, CA: A Cross-Sectional study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahn, B.A.; Bartholomew, T.S.; Patel, H.P.; Pastar, I.; Tookes, H.E.; Lev-Tov, H. Correlates of injection-related wounds and skin infections amongst persons who inject drugs and use a syringe service programme: A single Center Study. Int. Wound J. 2021, 18, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.; Oh, S. State-level Homelessness and Drug Overdose Mortality: Evidence from US panel data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2023, 250, 110910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholomew, T.S.; Tookes, H.E.; Bullock, C.; Onugha, J.; Forrest, D.W.; Feaster, D.J. Examining Risk Behavior and Syringe Coverage Among People Who Inject Drugs Accessing a Syringe Services Program: A Latent Class Analysis. Int. J. Drug Policy 2020, 78, 102716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, M.S.; Williams, A.; O’Rourke, A.; MacIntosh, E.; Moné, S.; Clay, C. The Impact of Housing Insecurity on Access to Care and Services Among People Who Use Drugs in Washington, DC. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, K.M.; Beech, E.H.; Williams, B.E.; Anderson, J.K.; Young, S.; Parr, N.J. Effectiveness of Syringe Service Programs: A systematic Review; Department of Veterans Affairs (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Executive Summary. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK598960 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Barocas, J.A.; Eftekhari Yazdi, G.; Savinkina, A.; Nolen, S.; Savitzky, C.; Samet, J.H.; Englander, H.; Linas, B.P. Long-Term Infective Endocarditis Mortality Associated With Injection Opioid Use in the United States: A Modeling Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e3661–e3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, A.M.; Falk, D.; Greenwood, H.; Gugerty, P.; Feinberg, J.; Friedmann, P.D.; Go, V.F.; Jenkins, W.D.; Korthuis, P.T.; Miller, W.C.; et al. Houselessness and Syringe Service Program Utilization Among People Who Inject Drugs in Eight Rural Areas Across the USA: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Harm Reduct. J. 2023, 20, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet. Housing: An Overlooked Social Determinant of Health. Lancet 2024, 403, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, S.; Garnham, L.; Godwin, J.; Anderson, I.; Seaman, P.; Donaldson, C. Housing as a Social Determinant of Health and Wellbeing: Developing an Empirically-Informed Realist Theoretical Framework. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantin, L.; Pasquarella, C.; Odone, A.; Colucci, M.E.; Costanza, A.; Serafini, G.; Aguglia, A.; Murri, M.B.; Brakoulias, V.; Amore, M.; et al. Screening for Depression in Primary Care with Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Level | Overall |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | — | 41.72 (13.81) |

| Sex, n (%) | Male | 104 (64.6) |

| Female | 57 (35.4) | |

| Race, n (%) | Black or African American | 131 (79.9) |

| White | 26 (15.9) | |

| Asian | 2 (1.2) | |

| Other Race | 3 (1.8) | |

| Unknown | 2 (1.2) | |

| Education, n (%) | High School Graduate or GED | 57 (35.0) |

| Some College | 39 (23.9) | |

| Some High School | 29 (17.8) | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 20 (12.3) | |

| Associate’s Degree | 9 (5.5) | |

| Other | 5 (3.1) | |

| Graduate Degree (Master’s, MD, PhD) | 4 (2.5) | |

| Employment, n (%) | Unemployed | 57 (35.0) |

| Employed full-time | 36 (22.1) | |

| Self-employed | 30 (18.4) | |

| Employed part-time | 22 (13.5) | |

| Receiving disability | 8 (4.9) | |

| Retired | 6 (3.7) | |

| Unable to work due to disability/injury | 2 (1.2) | |

| Other means of employment | 2 (1.2) | |

| Housing Stability, mean (SD) | — | 3.23 (2.43) |

| SSP Use, n (%) | No | 124 (77.0) |

| Yes | 37 (23.0) | |

| Opioid Use, n (%) | No | 81 (51.6) |

| Yes | 76 (48.4) | |

| Cocaine Use, n (%) | No | 61 (38.4) |

| Yes | 98 (61.6) | |

| Xanax Use, n (%) | No | 118 (74.2) |

| Yes | 41 (25.8) | |

| MDMA Use, n (%) | No | 107 (67.7) |

| Yes | 51 (32.3) | |

| Amphetamine Use, n (%) | No | 97 (61.4) |

| Yes | 61 (38.6) | |

| Footnote: Percentages are calculated using the number of respondents with non-missing data for each characteristic; totals may not sum to 100% due to rounding. | ||

| Outcome | Predictor | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overdose | Housing Stability | 1.34 (1.10–1.66) | 1.17 (0.94–1.48) | 0.178 |

| SSP Use | – | 4.04 (1.42–11.76) | 0.009 * | |

| Infections | Housing Stability | 1.55 (1.16–2.21) | 1.55 (1.16–2.21) | 0.0064 * |

| SSP Use | – | 3.92 (1.18–13.88) | 0.0273 * | |

| Opioid Use | – | 15.03 (2.67–284.90) | 0.0121 * | |

| Wounds | Housing Stability | 1.28 (0.99–1.69) | 1.28 (0.99–1.69) | 0.0667 |

| SSP Use | – | 4.50 (1.38–15.80) | 0.0142 * | |

| Opioid Use | – | 1.77 (0.50–7.24) | 0.392 | |

| Blackouts | Housing Stability | 1.47 (1.05–2.29) | 1.47 (1.05–2.29) | 0.0457 * |

| SSP Use | – | 4.89 (0.74–98.00) | 0.161 | |

| Unemployment Benefits | – | 4.38 (0.67–86.60) | 0.188 | |

| Seizures | Housing Stability | 1.54 (1.09–2.37) | 1.54 (1.09–2.37) | 0.0257 * |

| Xanax Use | – | 8.03 (1.84–43.35) | 0.0078 * | |

| Opioid Use | – | 6.77 (1.19–65.16) | 0.0530 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shanun, F.; Smith, D.J.; King, B.; Vlachou, L.; McGilvery, R.; Zine, S.; Henderson, H.; Reichman, E.; Cunningham, N.; Zare, M.; et al. The Housing Instability Scale: Determining a Cutoff Score and Its Utility for Contextualizing Health Outcomes in People Who Use Drugs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1653. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111653

Shanun F, Smith DJ, King B, Vlachou L, McGilvery R, Zine S, Henderson H, Reichman E, Cunningham N, Zare M, et al. The Housing Instability Scale: Determining a Cutoff Score and Its Utility for Contextualizing Health Outcomes in People Who Use Drugs. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1653. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111653

Chicago/Turabian StyleShanun, Fawaz, Daniel Jackson Smith, Beatrice King, Lydia Vlachou, Roesheen McGilvery, Stella Zine, Hayden Henderson, Emily Reichman, Nadiah Cunningham, Morgan Zare, and et al. 2025. "The Housing Instability Scale: Determining a Cutoff Score and Its Utility for Contextualizing Health Outcomes in People Who Use Drugs" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1653. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111653

APA StyleShanun, F., Smith, D. J., King, B., Vlachou, L., McGilvery, R., Zine, S., Henderson, H., Reichman, E., Cunningham, N., Zare, M., & Febres-Cordero, S. (2025). The Housing Instability Scale: Determining a Cutoff Score and Its Utility for Contextualizing Health Outcomes in People Who Use Drugs. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1653. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111653