Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Screening in Pediatric Primary Care: Is “Social Drivers of Health (SDoH) Screening” Sufficient?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

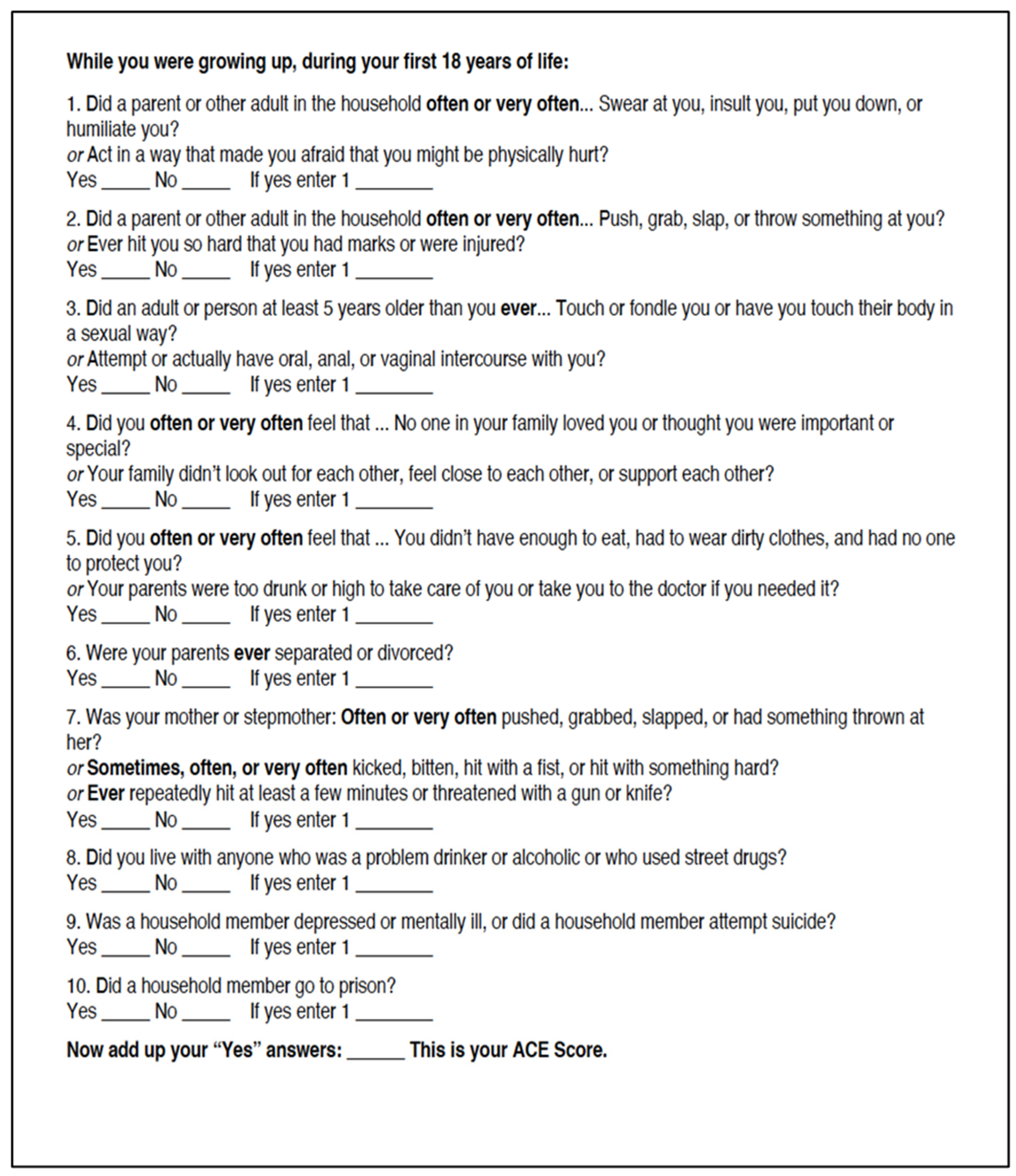

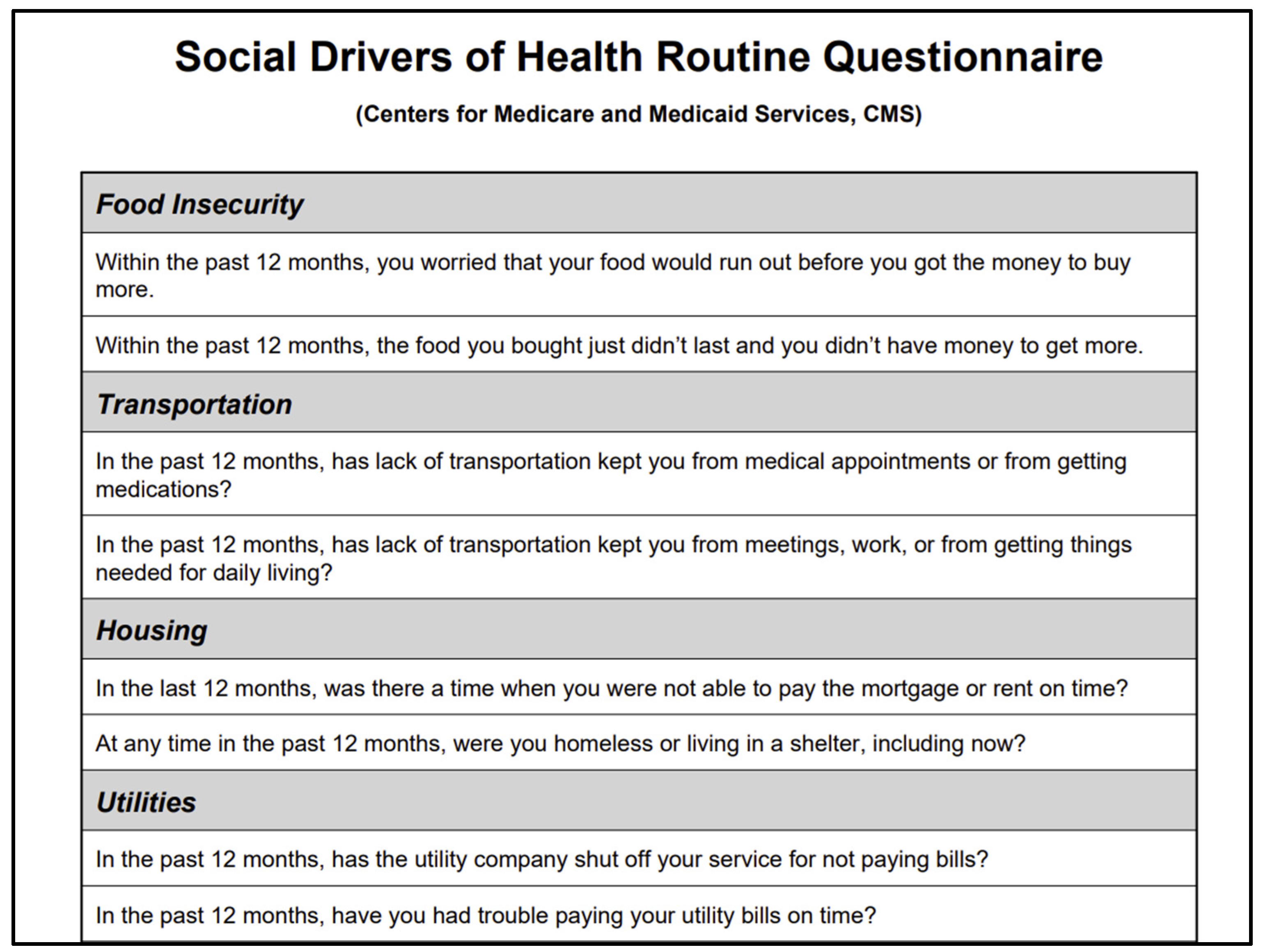

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Participant Responses to Screeners

3.3. Bivariate Analyses

3.4. Misclassification Rates (Table 5)

| Percentage | |

|---|---|

| False Positive Rate | 34.59 |

| False Negative Rate | 51.7 |

| Sensitivity | 48.3 |

| Specificity | 65.41 |

| Positive Predictive Value | 22.9 |

| Negative Predictive Value | 85.6 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACEs | Adverse Childhood Experiences |

| SDOH | Social Drivers of Health |

| IPV | Intimate Partner Violence |

| AAP | American Academy of Pediatrics |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

Appendix A

References

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.H.; Brown, D.C.; Walker, C.S.; Stubbs-Richardson, M.; Oliveros, A.D.; Buttross, S. Childhood adversity associated with poorer health: Evidence from the U.S. National Survey of Children’s Health. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 134, 105871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.M.; Zhang, C.; Bi, K.; Chen, M.S. Longitudinal impacts of adverse childhood experiences on multidimensional health outcomes: Predicting trajectories in mental, physical, and behavioral health. Child Abus. Negl. 2023, 168, 106543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemiyo, C.; McGregor, B.A.; Rehana, H.; Hur, J. Adverse childhood experiences and chronic health outcomes: Evidence from 33 US states in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2019–2023. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedo, E.A.; Aslam, M.V.; Dahlberg, L.L.; Niolon, P.H.; Guinn, A.S.; Simon, T.R.; Mercy, J.A. Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences Among U.S. Adults—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011–2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaoka, Y.; Bard, D.E. Positive Parenting Matters in the Face of Early Adversity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madigan, S.; Thiemann, R.; Deneault, A.-A.; Fearon, R.M.P.; Racine, N.; Park, J.; Lunney, C.A.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Jenkins, S.; Williamson, T.; et al. Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences in Child Population Samples: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2025, 179, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mersky, J.P.; Choi, C.; Plummer Lee, C.; Janczewski, C.E. Disparities in adverse childhood experiences by race/ethnicity, gender, and economic status: Intersectional analysis of a nationally representative sample. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 117, 105066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giano, Z.; Wheeler, D.L.; Hubach, R.D. The frequencies and disparities of adverse childhood experiences in the U.S. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus Post, L.; Topitzes, J.; Do, D.P.; Cho, Y.I.; Pathak, D.R.; Nuru-Jeter, A.; Kwarteng, J.L.; Dominguez, T.P.; Hamilton, A.S.; Hirko, K.A.; et al. Associations between childhood socioeconomic characteristics, race, and risk of adverse childhood experiences in a population-based sample of US-born non-Hispanic Black and White women. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, J.D.; MacMillan, H.L.; Afifi, T.O.; McTavish, J.; Gonzalez, A.; Waddell, C. Routine ACEs screening is NOT recommended. Paediatr. Child Health 2019, 24, 272–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, A.E.; Anderson, K.N.; Goodson, M.; Niolon, P.H.; Swedo, E.A.; Terranella, A.; Bacon, S. Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Critical Appraisal. Pediatrics 2024, 154, e2024067307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, D.; Hessler, D.; Koita, K.; Bucci, M.; Benson, M.; Gilgoff, R.; Thakur, N.; Burke Harris, N. Screening for adverse childhood experiences in pediatrics: A randomized trial of aggregate-level versus item-level response screening formats. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveday, S.; Hall, T.; Constable, L.; Paton, K.; Sanci, L.; Goldfeld, S.; Hiscock, H. Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences in Children: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2021051884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negriff, S.; DiGangi, M.J.; Sidell, M.; Liu, J.; Coleman, K.J. Assessment of Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences and Receipt of Behavioral Health Services Among Children and Adolescents. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2247421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negriff, S.; Sidell, M.; Barton, L.; DiGangi, M.J. Adverse childhood experiences screening in pediatric primary care and changes in the rate of visits to social work and behavioral health. BMC Pediatr. 2025, 25, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, D.; McCartney, G.; Smith, M.; Armour, G. Relationship between childhood socioeconomic position and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): A systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2019, 73, 1087–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.R.; Veliz, P.T.; Herrenkohl, T.I.; Miller, A.L.; V Pilkauskas, N.; Stoddard, S.A. Associations Among Childhood Household Income, Latent Classes of Early Adverse Childhood Experiences, and Adolescent Mental Health. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2025, 46, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radcliff, E.; Crouch, E.; Strompolis, M.; Srivastav, A. Homelessness in Childhood and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). Matern. Child Health J. 2019, 23, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.B.; Chilton, M.; Johnson, K.R.; Vaughn, M.G. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Household Food Insecurity: Findings From the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billioux, A.; Verlander, K.; Anthony, S.; Alley, D. Standardized Screening for Health-Related Social Needs in Clinical Settings: The Accountable Health Communities Screening Tool; NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper; National Academy of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, A.M.; Uthirasamy, N.; Porter, S.; Jimenez, M.E. Parental Depression Screening in Pediatric Health Care Settings: A Scoping Review. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2021055804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K.; Kochuparambil Sebastian, S.; Franck, G. Improving Domestic Violence Screening and Follow-Up in a Community Health Clinic. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2023, 14, 21501319231189074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renjilian, C.B.; Miller, V.; Ginsburg, K. Feasibility and Face Validity of a Modified Adverse Childhood Experiences (Aces) Inventory Formatted to Improve Youth Acceptance and Confidence with Participation in Research. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 62, S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mersky, J.P.; Gruber, A.M.H.; Kim, J.-Y. Intergenerational Transmission of Parental Adverse Childhood Experiences and Children’s Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2023, 24, 3251–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeCandia, C.J.; Volk, K.T.; Unick, G.J. Evolving Our Understanding: Housing Instability as an ACE for Young Children. Advers. Resil. Sci. 2022, 3, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Exner-Cortens, D.; Dobson, K.; Wells, L.; Noel, M.; Madigan, S. Adverse childhood experiences and intimate partner violence: A meta-analysis. Dev. Psychopathol. 2024, 36, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Caregiver | Child | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | 690 | 738 | 1428 |

| Average Age (SD) | 30.3 (±6.9) | 1.6 (±2.4) | --- |

| Sex (N(%) *) | |||

| Female | 43 (91.5) | 352 (49.0) | 395 (51.6) |

| Male | 4 (8.5) | 366 (51.0) | 370 (48.4) |

| Race (N(%)) | |||

| Black or African American | 10 (26.3) | 96 (15.1) | 106 (15.7) |

| Latinx | 21 (55.3) | 506 (79.4) | 527 (78.1) |

| White | 1 (2.6) | 14 (2.2) | 15 (2.2) |

| Asian American, Pacific Islander | 0 | 5 (0.8) | 5 (0.7) |

| Other | 6 (15.8) | 16 (2.5) | 22 (3.3) |

| Missing | 29 | 724 | 753 |

| Primary Language (N(%)) | |||

| English | 26 (55.3) | 359 (50.1) | 385 |

| Spanish | 14 (29.8) | 317 (44.3) | 331 |

| Other | 7 (14.9) | 40 (5.6) | 47 |

| Missing | 20 | 645 | 665 |

| Screen Positive | Screen Negative | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver | Child | Caregiver | Child | |

| ACEs | 74 (10.7) | 138 (18.7) | 616 (89.3) | 600 (81.3) |

| SDOHs (any insecurity) | 123 (37.8) | 187 (36.5) | 202 (62.2) | 326 (63.5) |

| Utilities | 12 (3.7) | 28 (5.8) | 309 (96.3) | 456 (94.2) |

| Transportation | 34 (10.5) | 50 (10.3) | 290 (89.5) | 437 (89.7) |

| Housing | 73 (23.3) | 102 (20.8) | 240 (76.7) | 388 (79.2) |

| Food | 68 (21.6) | 99 (19.8) | 247 (78.4) | 402 (80.2) |

| Intimate Partner Violence | 15 (4.9) | 21 (4.4) | 289 (95.1) | 460 (95.6) |

| Maternal Depression | 20 (27.4) | 28 (30.1) | 53 (72.6) | 65 (69.9) |

| Positive Child ACEs | Negative Child ACEs | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive SDOHs (any insecurity) | 46 (24.6% had a positive ACE out of those with positive SDOH) | 141 (75.4% had a negative ACE out of those with positive SDOH) |

| Negative SDOHs (any insecurity) | 59 (18.1) | 267 (81.9) |

| p = 0.079 | ||

| Positive Utilities | 7 (25) | 21 (75) |

| Negative Utilities | 92 (20.2) | 364 (79.8) |

| p = 0.539 | ||

| Positive Transportation | 11 (22) | 39 (78) |

| Negative Transportation | 89 (20.4) | 348 (79.6) |

| p = 0.786 | ||

| Positive Housing | 30 (29.4) | 72 (70.6) |

| Negative Housing | 71 (18.3) | 317 (81.7) |

| p = 0.014 | ||

| Positive Food | 20 (20.2) | 79 (79.8) |

| Negative Food | 82 (20.4) | 320 (79.6) |

| p = 0.965 | ||

| Positive IPV | 8 (38.1) | 13 (61.9) |

| Negative IPV | 91 (19.8) | 369 (80.2) |

| p = 0.053 | ||

| Positive Depression | 10 (35.7) | 18 (64.3) |

| Negative Depression | 19 (29.2) | 46 (70.8) |

| p = 0.5358 | ||

| Positive Caregiver ACEs | Negative Caregiver ACEs | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive SDOHs (any insecurity) | 25 (20.3% had a positive ACEs out of those with positive SDOH) | 98 (79.7% had a negative ACEs out of those with positive SDOH) |

| Negative SDOHs (any insecurity) | 17 (8.4) | 185 (91.6) |

| p = 0.002 | ||

| Positive Utilities | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) |

| Negative Utilities | 40 (12.9) | 269 (87) |

| p = 0.661 | ||

| Positive Transportation | 7 (20.6) | 27 (79.4) |

| Negative Transportation | 35 (12.1) | 255 (87.9) |

| p = 0.176 | ||

| Positive Housing | 17 (23.3) | 56 (76.7) |

| Negative Housing | 24 (10) | 216 (90) |

| p = 0.003 | ||

| Positive Food | 12 (17.6) | 56 (82.4) |

| Negative Food | 28 (11.3) | 219 (88.7) |

| p = 0.166 | ||

| Positive IPV | 4 (26.7) | 11 (73.3) |

| Negative IPV | 33 (11.4) | 256 (88.6) |

| p = 0.095 | ||

| Positive Depression | 4 (20) | 16 (80) |

| Negative Depression | 10 (18.9) | 43 (81.1) |

| p = 1.0 | ||

| Number of ACE’s Endorsed | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | 44% | 50% | 73% | 67% |

| Caregiver | 40% | 44% | 53% | 60% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zielinski, S.; Valdez, J.; James, J.; Gates, J.; Patel, B.; Gissandaner, T.D.; Feurstein, R.; Levy, R.; Vargas, W.; Berger-Jenkins, E. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Screening in Pediatric Primary Care: Is “Social Drivers of Health (SDoH) Screening” Sufficient? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111644

Zielinski S, Valdez J, James J, Gates J, Patel B, Gissandaner TD, Feurstein R, Levy R, Vargas W, Berger-Jenkins E. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Screening in Pediatric Primary Care: Is “Social Drivers of Health (SDoH) Screening” Sufficient? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111644

Chicago/Turabian StyleZielinski, Sylvia, Jocelyn Valdez, Juliana James, Jennifer Gates, Bhavik Patel, Tre DeVon Gissandaner, Rachel Feurstein, Ryan Levy, Wanda Vargas, and Evelyn Berger-Jenkins. 2025. "Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Screening in Pediatric Primary Care: Is “Social Drivers of Health (SDoH) Screening” Sufficient?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111644

APA StyleZielinski, S., Valdez, J., James, J., Gates, J., Patel, B., Gissandaner, T. D., Feurstein, R., Levy, R., Vargas, W., & Berger-Jenkins, E. (2025). Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Screening in Pediatric Primary Care: Is “Social Drivers of Health (SDoH) Screening” Sufficient? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111644