Exploring How Intent of Self-Harm Affects Trainee Healthcare Practitioners’ Views, Attitudes and Clinical Decision-Making in Northwest England: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Analysis

2.6. Reflexivity and Trustworthiness

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

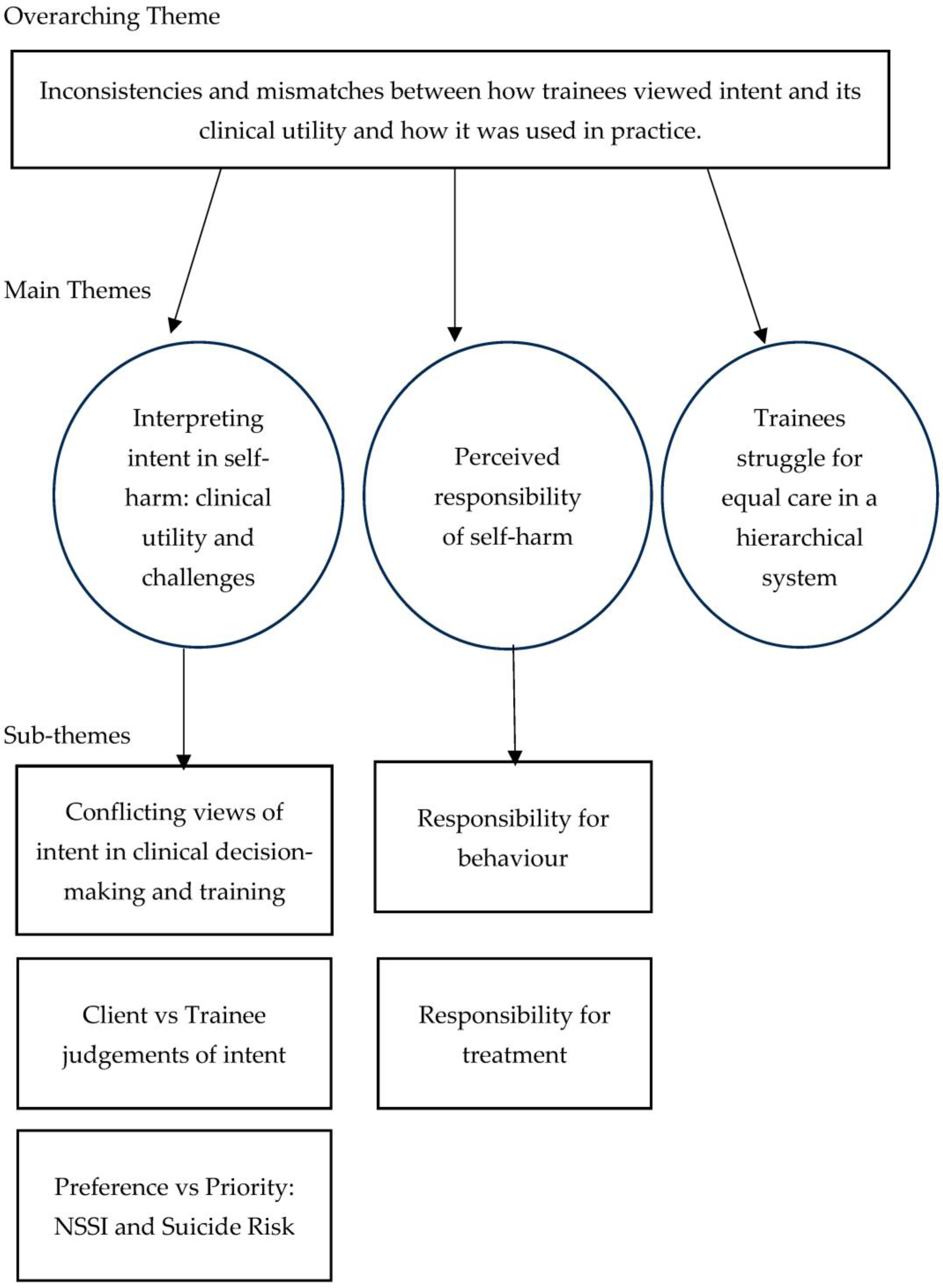

3.2. Thematic Analysis

3.2.1. Interpreting Intent in Self-Harm: Clinical Utility and Challenges

Conflicting Views of Intent in Clinical Decision-Making and Training

Client vs. Trainee Judgements of Intent

Preference vs. Priority: NSSI and Suicide Risk

3.2.2. Perceived Responsibility of Self-Harm

Responsibility for Behaviour

Responsibility for Treatment

3.2.3. Trainees Struggle for Equal Care in a Hierarchical System

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioural Therapy |

| DClinPsy | Doctorate of Clinical Psychology |

| DCounPsy | Doctorate of Counselling Psychology |

| DBT | Dialectical Behavioural Therapy |

| M | Mean |

| NAP | Nursing Associate Practitioner |

| NSSI | Non-Suicidal Self-Injury |

| RTA | Reflexive Thematic Analysis |

| SA | Suicide Attempt |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TAPP | Trainee Associate Psychological Practitioner |

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Self-Harm: Assessment, Management and Preventing Recurrence [NICE Guideline No. 225]. 2022. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng225 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Knipe, D.; Padmanathan, P.; Newton-Howes, G.; Chan, L.F.; Kapur, N. Suicide and self-harm. Lancet 2022, 399, 1903–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McManus, S.; Bebbington, P.; Jenkins, R.; Brugha, T. Mental Health and Wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. NHS England. 2016. Available online: http://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB21748 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Morris, S.; Hill, S.; Brugha, T. (Eds.) Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey: Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, England, 2023/24; NHS England Digital: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J.C. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Diaz, M. The stigma of self-harm: Public perceptions and professional bias. J. Ment. Health 2021, 30, 421–429. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, B.; Blazely, A.; Phillips, L. Stigma towards individuals who self-harm: Impact of gender and disclosure. J. Public Ment. Health 2018, 17, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, C.; Bale, C. A qualitative analysis of perceptions of self-harm in members of the general public. J. Public Ment. Health 2012, 11, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickell, T.A.; McLean, C. Emerging issues and challenges for improving patient safety in mental health: A qualitative analysis of expert perspectives. J. Patient Saf. 2011, 7, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, D.; Pratto, D.A. Mental health services for individuals at risk of suicide in Peru: Attitudes and perspectives of mental health professionals. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michall, C.; Tait, L.; Churchill, R. Stigma towards people who self-harm: Attitudes of nurses in a UK mental health trust. Ment. Health Pract. 2017, 20, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, N.; Rapport, F.; Thomas, G.; John, A.; Snooks, H. Perceptions of paramedic and emergency care workers of those who self-harm: A systematic review of the quantitative literature. J. Psychosom. Res. 2014, 77, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, N.; Porter, A.; Rapport, F.; Hughes, S.; John, A. Paramedics’ perceptions of the care they provide to people who self-harm: A qualitative study using evolved grounded theory methodology. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGough, S.; Wynaden, D.; Ngune, I.; Janerka, C.; Hasking, P.; Rees, C. Emergency nurses’ perceptions of the health care system and how it impacts provision of care to people who self-harm. Collegian 2022, 29, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, S.; Suzuki, M.; Ryan, M.; Hunter, J.; McCabe, R. Experiences of care for self-harm in the emergency department: Comparison of the perspectives of patients, carers and practitioners. BJPsych Open 2021, 7, e175–e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, P.; Hurry, J.; Jowitt, S.; Owens, D.; House, A. Supporting young people who repeatedly self-harm. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 2005, 125, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinola, M.; Rayner, G. Stigma and self-harm: Service users’ experiences. J. Ment. Health 2022, 31, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.N.; Wells, K.M.; Joy-Gaba, J.A.; Hawkins, C.B.; Nosek, B.A. Do physicians’ implicit views of African Americans affect clinical decision making? J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2014, 27, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuku, S. Self-harm presentations in emergency departments: Staff attitudes and triage. Br. J. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1468–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, G.; Blackburn, J.; Edward, K.L.; Stephenson, J.; Ousey, K. Emergency department nurse’s attitudes towards patients who self-harm: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, T.L.; Hawton, K.; Fortune, S.; Kapur, N. Attitudes towards clinical services among people who self-harm: Systematic review. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 194, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergen, C.; Lomas, M.; Ryan, M.; McCabe, R. Gatekeeping and factors underlying decisions not to refer to mental health services after self-harm: Triangulating video-recordings of consultations, interviews, medical records and discharge letters. SSM-Qual. Res. Health 2023, 4, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, R.; Martin, C. Perceptions of Australian emergency staff towards patients presenting with deliberate self-poisoning: A qualitative perspective. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2014, 22, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, S.; Gunnell, D.; Cooper, C.; Bebbington, P.E.; Howard, L.M.; Brugha, T.; Jenkins, R.; Hassiotis, A.; Weich, S.; Appleby, L. Prevalence of non-suicidal self-harm and service contact in England, 2000–14: Repeated cross-sectional surveys of the general population. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, M.; Casey, L.; Rando, N.; O’Gorman, J. Stigma and help-seeking behaviour for self-harm: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicka, J.; Kiejna, A. Differences between suicide and non-suicidal self-harm behaviours: A literary review. Arch. Psychiatry Psychother. 2015, 3, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.; Xyrichis, A.; Leamy, M.C.; Reynolds, E.; Maben, J. Can Schwartz Center Rounds support healthcare staff with emotional challenges at work, and how do they compare with other interventions aimed at providing similar support? A systematic review and scoping reviews. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e024254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halicka, J.; Kiejna, A. Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicidal: Criteria differentiation. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 27, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samari, E.; Shahwan, S.; Abdin, E.; Zhang, Y.; Sambasivam, R.; Teh, W.L.; Ong, S.H.; Chong, S.A.; Subramaniam, M. An exploration of differences between deliberate self-harm with and without suicidal intent amongst a clinical sample of young people in Singapore: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, S.; Choo, T.-H.; Galfalvy, H.; Mann, J.J.; Stanley, B.H. Effect of non-suicidal self-injury on suicidal ideation: Real-time monitoring study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2022, 221, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia-Pereira, M.; Duarte, E.; Gomes, H.S.; da Silva, C.T.; Santos, N. Exploring the suicidal continuum. Deliberate self-harm diversity and severity as predictors of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 309, 114400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehlenkamp, J.J. Self-injury and suicide behavior: A review for clinicians. J. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 70, 279–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kapur, N.; Cooper, J.; O’Connor, R.C.; Hawton, K. Non-suicidal self-injury v. attempted suicide: New diagnosis or false dichotomy? Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 202, 326–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar Ray, M.; Wyder, M.; Crompton, D.; Kousoulis, A.A.; Arensman, E.; Hafizi, S.; Van Bortel, T.; Lombardo, C. PROTECT: Relational safety based suicide prevention training frameworks. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawton, K.; Harriss, L.; Hall, S.; Simkin, S.; Bale, E.; Bond, A. Deliberate selfharm in Oxford, 1990–2000: A time of change in patient characteristics. Psychol. Med. 2003, 33, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGough, S.; Wynaden, D.; Ngune, I.; Janerka, C.; Hasking, P.; Rees, C. Mental health nurses’ perspectives of people who self-harm. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ougrin, D.; Tranah, T.; Stahl, D.; Moran, P.; Asarnow, J.R. Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: Systematic review and metaanalysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 54, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.M.; Malone, K. Attempted suicide v. non-suicidal self-injury: Behaviour syndrome or diagnosis? Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 202, 324–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, K.J.; Klonsky, E.D.; Selby, E.A. Advancing theory of suicide and non-suicidal self-injury. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 780029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynders, A.; Kerkhof, A.J.; Molenberghs, G.; Van Audenhove, C. Attitudes and stigma in relation to help-seeking intentions for psychological problems in low and high suicide rate regions. Soc. Psychiatry 2014, 49, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, P.W. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am. Psychol. 2003, 59, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. Controllability beliefs and stigma in self-harm. J. Ment. Health 2016, 25, 224–230. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, T.M.; Hawley, C.J.; Butler, J.; Morton, A.; Singhal, A. Perception of suicide risk in mental health professionals. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senf, B.; Maiwurm, P.; Fettel, J. Attitudes and opinions towards suicidality in professionals working with oncology patients: Results from an online survey. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 1775–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Zhao, R.; Zhuo, Y.; Kou, X.; Yu, J. Experiences and attitudes of psychiatric nurses in caring for patients with repeated non-suicidal self-injury in China: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniland, L.; Hasking, P.; Boyes, M.; Lewis, S. Stigma and nonsuicidal self-injury: Application of a conceptual framework. Stigma Health 2021, 6, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, K.; Deane, F.P.; Miller, L.M. Beliefs about the function of self-harm and stigmatizing responses: Testing the attribution model and a novel psychophysical response measure. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 15771–15786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, H.; Svensson, E.; Magnusson, A.; Holmqvist, R.; Zetterqvist, M. Young adults looking back at their experiences of treatment and care for non-suicidal self-injury during adolescence: A qualitative study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2024, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiran, T.; Chaudhry, N.; Bee, P.; Tofique, S.; Farooque, S.; Taylor, A.K.; Husain, N.; Chew-Graham, C.A. Clinicians’ perspectives on self-harm in Pakistan: A qualitative study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 607549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay, N.; Barrowclough, C. Accident and emergency staff’s perceptions of deliberate self-harm: Attributions, emotions and willingness to help. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 44, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppich, W.J.; Gormley, G.J.; Teunissen, P.W. In-depth interviews. In Healthcare Simulation Research: A Practical Guide; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, P.; Richards, D. Critical realism: A way forward for evaluation research in nursing? J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 43, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, T. Establishing rigour in qualitative research: The decision trail. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 53, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.C.; Nock, M.K. The psychology of suicidal behaviour. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.M. Understanding Therapist Experiences When Organisational Risk Management Protocols Are Implicated by the Suicidal Ideation and Intent of Clients. Ph.D. Thesis, University of London, London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Flintoff, A.; Speed, E.; McPherson, S. Risk assessment practice within primary mental health care: A logics perspective. Health 2019, 23, 656–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.H.S.; Shahwan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Sambasivam, R.; Ong, S.H.; Subramaniam, M. How do professionals and non-professionals respond to non-suicidal self-injury? Lived experiences of psychiatric outpatients in Singapore. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, R.; Garside, R.; Backhouse, A.; Xanthopoulou, P. Effectiveness of brief psychological interventions for suicidal presentations: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Bustos, P.; Calati, R.; Rubio-Ramírez, F.; Olié, E.; Courtet, P.; Lopez-Castroman, J. Effectiveness of psychotherapy on suicidal risk: A systematic review of observational studies. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graney, J.; Hunt, I.M.; Quinlivan, L.; Rodway, C.; Turnbull, P.; Gianatsi, M.; Appleby, L.; Kapur, N. Suicide risk assessment in UK mental health services: A national mixed-methods study. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuji, C.; van Ballegooijen, W.; De Beurs, D.; Juniar, D.; Erlangsen, A.; Portzky, G.; O’Connor, R.C.; Smit, J.H.; Kerkhof, A.; Riper, H. Safety planning-type interventions for suicide prevention: Meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2021, 219, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchant, A.; Turner, S.; Balbuena, L.; Peters, E.; Williams, D.; Lloyd, K.; Lyons, R.; John, A. Self-harm presentation across healthcare settings by sex in young people. Int. J. Popul. Data Sci. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, S.J.; Beautrais, A.L.; Surgenor, L.J. Health-care staff attitudes towards self-harm patients. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2010, 44, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlivan, L.M.; Gorman, L.; Littlewood, D.L.; Monaghan, E.; Barlow, S.J.; Campbell, S.M.; Webb, R.T.; Kapur, N. ‘Relieved to be seen’—Patient and carer experiences of psychosocial assessment in the emergency department following self-harm: Qualitative analysis of 102 free-text survey responses. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlivan, L.; Gorman, L.; Littlewood, D.L.; Monaghan, E.; Barlow, S.; Campbell, S.; Gooding, P.; Kapur, N. “Wasn’t offered one, too poorly to ask for one”—Reasons why some patients do not receive a psychosocial assessment following self-harm: Qualitative patient and carer survey. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2021, 56, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, K.E.; Hawton, K.; Fortune, S.; Farrell, S. Attitudes and knowledge of clinical staff regarding people who self-harm: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 139, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Y.; Krysinska, K.; Byrne, S.J.; Boland, A.; Michail, M.; Lamblin, M.; Gibson, K.L.; Lin, A.; Li, T.Y.; Hetrick, S.; et al. Best practice when working with suicidal behaviour and self-harm in primary care: A qualitative exploration of young people’s perspectives. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e038855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, S.; Rakow, T. Assessing risk and prioritizing referral for self-harm: When and why is my judgement different from yours? Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2012, 19, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolochowski, F.D.; Kreckeler, N.; Forkmann, T.; Teismann, T. Reliability of suicide risk estimates: A vignette study. Arch. Suicide Res. 2025, 29, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewick, B.M.; McBride, J.; Barkham, M. When clients and practitioners have differing views of risk: Benchmarks for improving assessment and practice. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2006, 6, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S. Self-harm and the words that bind: A critique of common perspectives. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2007, 14, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, W.; Leitner, M.; Thomas, J. Short shrift for the sane? The hospital management of self-harm patients with and without mental illness. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2004, 11, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, M.L.; Gorday, J.Y.; Joiner, T.E. Examination of characteristics of ruminative thinking as unique predictors of suicide-related outcomes. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 139, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paashaus, L.; Forkmann, T.; Glaesmer, H.; Juckel, G.; Rath, D.; Schönfelder, A.; Teismann, T. From decision to action: Suicidal history and time between decision to die and actual suicide attempt. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2021, 28, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Hyun, M.H. Task control deficit in individuals with non-suicidal self-injury. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 608357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, P. Emotion Reactivity, Emotion Dysregulation, and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Among at Risk Adolescents: A Multiple Mediation Analysis. Master’s Thesis, University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fikke, L.T.; Melinder, A.; Landrø, N.I. Executive functions are impaired in adolescents engaging in non-suicidal self-injury. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobes, D.A.; Chalker, S.A. One size does not fit all: A comprehensive clinical approach to reducing suicidal ideation, attempts, and deaths. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, A.; Baruch, Y.; Hirschmann, S.; Lubin, G.; Melamed, Y.; Zemishlany, Z.; Kaplan, Z.E. Management of the suicidal patient in the era of defensive medicine: Focus on suicide risk assessment and boundaries of responsibility. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2011, 13, 653–656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Høifødt, T.S.; Talseth, A.G. Dealing with suicidal patients–a challenging task: A qualitative study of young physicians’ experiences. BMC Med. Educ. 2006, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobes, D.A. Common sense recommendations for standard care of suicidal risk. J. Health Serv. Psychol. 2020, 46, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamblin, K.; McNaughton, R.J.; Raby, P. “I haven’t got a clue what policies are in place for this!”: Physiotherapy students’ preparedness to deal with self-harm. Physiotherapy 2024, 124, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veresova, M.; Michail, M.; Richards, H.; Witt, K.; Lamblin, M.; Bleeker, C.; Robinson, J. Emergency department staff experiences of working with people who self-harm: A qualitative examination of barriers to optimal care. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2024, 33, 1482–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahn, R.J.; Quinnett, P.; Ries, R. The influence of training and experience on mental health practitioners’ comfort working with suicidal individuals. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2016, 47, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrik, M.L.; Gutierrez, P.M.; Berlin, J.S.; Saunders, S.M. Barriers and facilitators of suicide risk assessment in emergency departments: A qualitative study of provider perspectives. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2015, 37, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhugra, D.; Easter, A.; Mallaris, Y.; Gupta, S. Clinical decision making in psychiatry by psychiatrists. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2011, 124, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thexton, W. Clinical Psychology Training and Preparation for Multidisciplinary Team Working: A Grounded Theory Model and the Reframing of Reflective Practice. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stockton, I.; Warner, M. Ethnic Diversity of NHS Doctors (IFS Report No. R294); Ethnic diversity of NHS doctors; Institute for Fiscal Studies: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Leather, J.Z.; O’Connor, R.C.; Quinlivan, L.; Kapur, N.; Campbell, S.; Armitage, C.J. Healthcare professionals’ implementation of national guidelines with clients who self-harm. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 130, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodford, R.; Spittal, M.J.; Milner, A.; McGill, K.; Kapur, N.; Pirkis, J.; Mitchell, A.; Carter, G. Accuracy of clinician predictions of future self-harm: A systematic review and meta-analysis of predictive studies. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, R.; Newton-Howes, G.; Coid, J.W. The futility of risk prediction in psychiatry. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 209, 271–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kool, N.; van Meijel, B.; Koekkoek, B.; van der Bijl, J.; Kerkhof, A. Improving communication and practical skills in working with inclients who self-harm: A pre-test/posttest study of the effects of a training programme. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellairs-Walsh, I.; Byrne, S.J.; Bendall, S.; Perry, Y.; Krysinska, K.; Lin, A.; Michail, M.; Lamblin, M.; Li, T.Y.; Hetrick, S.; et al. Working with young people at risk of suicidal behaviour and self-harm: A qualitative study of Australian General Practitioners’ perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppens, E.; Van Audenhove, C.; Gusmão, R.; Purebl, G.; Székely, A.; Maxwell, M.; Koburger, N.; Arensman, E.; Hegerl, U. Effectiveness of general practitioner training to improve suicide awareness and knowledge and skills towards depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 227, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michail, M.; Tait, L.; Churchill, D. General practitioners’ clinical expertise in managing suicidal young people: Implications for continued education. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2017, 18, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.; Carson, J.; Houghton, T. Stigma towards non-suicidal self-harm: Evaluating a brief educational intervention. Br. J. Nurs. 2019, 28, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karman, P.; Kool, N.; Poslawsky, I.E.; Van Meijel, B. Nurses’ attitudes towards self-harm: A literature review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 22, 6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.; Davies, B. No blame no gain? From a no blame culture to a responsibility culture in medicine. J. Appl. Philos. 2020, 37, 646–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belford, A.J. No blame policy is not no blame culture. BMJ 2023, 383, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.; Schache, K.; Young, M.; Sinclair, J. Value of Schwartz Rounds in promoting the emotional well-being of healthcare workers: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e064144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, H.; Ward, L. Responsibility without blame: Philosophical reflections on clinical practice. In The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Psychiatry; Fulford, K.W.M., Davies, M., Gipps, R., Graham, G., Sadler, J., Stanghellini, G., Thornton, T., Eds.; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 1134–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Østervang, C.; Touborg Lassen, A.; Stenager, E.; Valdersdorf Jensen, M. Experiences of nursing care for patients who self-harm and suggestions for future practices: The perspectives of emergency care nurses. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 31, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulter, A.; Edwards, A.; Elwyn, G.; Thomson, R. Implementing shared decision making in the UK. Z. Evidenz Fortbild. Qual. Gesundheitswesen 2011, 105, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, C.M. How I stopped dreading and learned to love transcription. Qual. Inq. 2025, 11, 226–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rizq, R.; Target, M. ‘The power of being seen’: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of how experienced counselling psychologists describe the meaning and significance of personal therapy in clinical practice. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2008, 36, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | N |

|---|---|

| Age M ± (SD) | 29.2 ± (8.02) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 14 |

| Non-binary | 1 |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 15 |

| Programme | |

| DClinPsy 1 | 5 |

| Mental Health Nursing | 3 |

| Medicine | 3 |

| TAPP 2 | 2 |

| DCounPsy 3 | 1 |

| NAP 4 | 1 |

| Lived experience of self-harm | |

| Yes | 8 |

| No | 7 |

| Personally know someone who has self-harmed | |

| Yes, close family/friend | 12 |

| Yes, distant family/friend | 2 |

| No | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kumari, D.P.; Gardner, K.J.; Taylor, P. Exploring How Intent of Self-Harm Affects Trainee Healthcare Practitioners’ Views, Attitudes and Clinical Decision-Making in Northwest England: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101563

Kumari DP, Gardner KJ, Taylor P. Exploring How Intent of Self-Harm Affects Trainee Healthcare Practitioners’ Views, Attitudes and Clinical Decision-Making in Northwest England: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101563

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumari, Destiny Priya, Kathryn Jane Gardner, and Peter Taylor. 2025. "Exploring How Intent of Self-Harm Affects Trainee Healthcare Practitioners’ Views, Attitudes and Clinical Decision-Making in Northwest England: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101563

APA StyleKumari, D. P., Gardner, K. J., & Taylor, P. (2025). Exploring How Intent of Self-Harm Affects Trainee Healthcare Practitioners’ Views, Attitudes and Clinical Decision-Making in Northwest England: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101563