Improving Peer Relationships Through Positive Deviance Practices and the HOPE (Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences) Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Positive Deviance Approach

1.2. Applications of PD Across Contexts

1.3. Positive Childhood Experiences

1.4. Theortetical Framework

1.5. Boys & Girls Clubs of Monmouth County

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting/Participants

2.2. Positive Deviance Inquiry

2.2.1. Procedure

2.2.2. Discovery and Action Dialogues

2.2.3. Focus Groups

2.2.4. Staff Observations

2.3. Intervention (Training) Design and Implementation

2.3.1. Training Design

2.3.2. Training Implementation

2.4. Outcome Measures/Data Collection (Post-Intervention Focus Groups)

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Member Checking

3. Results

3.1. Discovery and Action Dialogs (DADs)

3.2. Pre-Intervention Focus Groups

3.2.1. Analysis of Staff Focus Groups

3.2.2. Analysis of Member Focus Groups

3.3. Analysis of Staff Observations

3.4. Positive Deviants and Practices Identified

- Emotional Check-ins: Emphasizing the importance of individual and group emotional check-ins to foster environments where youth feel heard, seen, and supported, ultimately contributing to effective problem-solving.

- Peer-to-Peer Conflict Resolution: Promoting strategies for resolving conflicts among peers and encouraging collaboration through intentionally mixed team membership.

- Youth Leadership and Voice: Creating structured opportunities for youth to take on leadership roles, contribute to program design, and reflect on their experiences within programs.

3.5. Post-Intervention Focus Groups

3.5.1. Staff Focus Groups

3.5.2. Member Focus Groups

3.6. Pre- & Post-Intervention Focus Group Comparison

3.7. Analysis of Member Checking

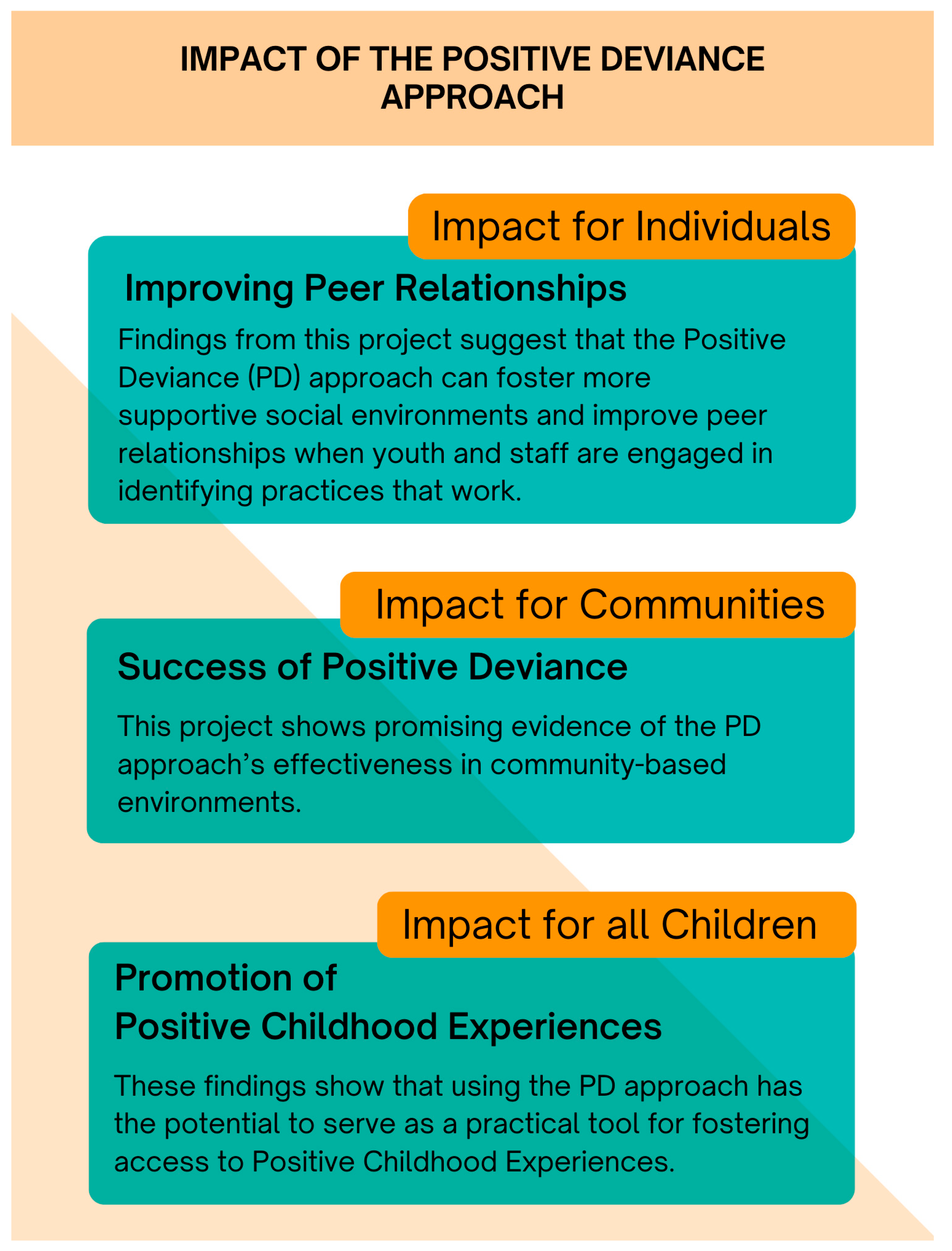

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCEs | Positive childhood experiences |

| PD | Positive deviance |

| PDs | Positive deviants |

| BGCM | The Asbury Park location of the Boys & Girls Clubs of Monmouth County |

| HOPE | Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences |

| DADs | Discovery and Action Dialogues |

| DMS | Data Must Speak |

| CIT | Counselor in Training |

| QI | Quality Improvement |

Appendix A

| Questions |

|---|

| How do you know or recognize when children are at risk or suffering from toxic stress or childhood trauma? |

| What do you help reduce the risk or help children heal from toxic stress or trauma? |

| What prevents you from taking these actions all the time (personal or organizational roadblocks?) |

| Is there anyone you know who is able to frequently reduce the risk, or overcome the barriers? Someone who despite the challenges has really caring and competent relationships with students, helps students regulate and gets better engagement? What do they do? |

| Do you have any recent experiences where engagement was exceptional? Less than ideal? |

| Do you have any ideas to help students who are experiencing toxic stress or childhood trauma? |

| What needs to be done to make it happen? Any volunteers? |

| Time | Workshop Content | Facilitator | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 min | Introduce PD * Work | BGCM ** senior leadership | |

| 20–30 min | Run Scenarios (5 min each) Brief description (1–2 min) from each PD following their scenario describing their experience with using this practice. | Designated PD to present—Opportunities and Expectations (Youth Voice and Choice) Designated PD to present—Supportive Relationships (solving problems) Designated PD to present—Supportive Relationships (Conflict Resolution) Designated PD to present—Fun and Recognition Designated PD to present—Safe and Positive Environment (self-regulation) | 5 key elements of positive youth development Opportunities and Expectations Supportive relationships Fun and Recognition Safe and positive environment Change the scenarios for the booster session |

| 10 Minutes | Process Scenarios | What did you notice? Did you see an intervention that seemed to be effective? Which one? | |

| Lunch | |||

| 15 min | Teach Back Sessions | Break participants into 5 groups Assign each group to a PD PD researchers and BGCM staff leadership rotate around room to each small group PD’s review their role play scenario. Have participants volunteer to play a role in that scenario and role play the practices observed in the scenarios. Allow for several rounds of switching roles if time allows. 2 min before the session ends ask: What was it like? Can you imagine yourself using these practices in the club? End session and have group rotate to the next PD session. | |

| 10 min | Facilitation idea:

| How did it go? What did we learn ab these new practices? What did we notice about the impact? Do you have more ideas of how to reach more staff and members? | |

| Closing | Wrap up | BGCM senior leadership | |

| Project Month(s) | Project Phase | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| 1–4 | Planning |

|

| 5–10 | PD ** Inquiry |

|

| 11–15 | PD Practice Identification and Training Development |

|

| 16–18 | Implementation |

|

| 21 | Post-Implementation Data Collection |

|

| 22–24 | Data Analysis |

|

| 24 | Member Checking |

|

References

- Positive Deviance Collaborative. Positive Deviance. Available online: https://positivedeviance.org/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Marsh, D.R.; Schroeder, D.G.; Dearden, K.A.; Sternin, J.; Sternin, M. The power of positive deviance. BMJ 2004, 329, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascale, R.T.; Sternin, J.; Sternin, M. The Power of Positive Deviance: How Unlikely Innovators Solve the World’s Toughest Problems; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, R.; O’Connor, P.; Madden, C.; Lydon, S. A systematic review of the use of positive deviance approaches in primary care. Fam. Pract. 2022, 39, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassie, A.M.; Eakin, E.; Abate, B.B.; Endalamaw, A.; Zewdie, A.; Wolka, E.; Assefa, Y. The use of positive deviance approach to improve health service delivery and quality of care: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, C.M.; Lindberg, C.C.; D’Agata, E.M.C.; Esposito, B.; Downham, G. Advancing Antimicrobial Stewardship in Outpatient Dialysis Centers Using the Positive Deviance Process. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 2019, 46, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ponte, E. Success in Education by Defying Great Odds: A Positive Deviance Analysis of Educational Policies. Cent. Educ. Policy Stud. J. 2024, 14, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durá, L.; Singhal, A. Will Ramón Finish Sixth Grade? Positive Deviance for Student Retention in Rural Argentina; Positive Deviance Initiative: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF, for Every Child. Applying Positive Deviance for Every Child; UNICEF for Every Child: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stanford University K12 Lab. Positive Deviance for Educators. Available online: https://dschool.stanford.edu/k12-lab-network/positive-deviance-for-educators?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Bethell, C.; Jones, J.; Gombojav, N.; Linkenbach, J.; Sege, R. Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Mental and Relational Health in a Statewide Sample: Associations Across Adverse Childhood Experiences Levels. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, e193007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graupensperger, S.; Kilmer, J.R.; Olson, D.C.D.; Linkenbach, J.W. Associations Between Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Smoking and Alcohol Use Behaviors in a Large Statewide Sample. J. Community Health 2023, 48, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hero, J.; Gallant, L.; Burstein, D.; Newberry, S.; Qureshi, N.; Feistel, K.; Anderson, K.N.; Hannan, K.; Sege, R. Health Associations of Positive Childhood Experiences: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.X.; Halfon, N.; Sastry, N.; Chung, P.J.; Schickedanz, A. Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Health Outcomes. Pediatrics 2023, 152, e2022060951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sege, R.D.; Aslam, M.V.; Peterson, C.; Bethell, C.; Burstein, D.; Niolon, P.H.; Jones, J.; Ettinger de Cuba, S.; Hannan, K.; Swedo, E.A. Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Health and Opportunity Outcomes in 4 US States. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2524435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sege, R.D.; Harper Browne, C. Responding to ACEs with HOPE: Health Outcomes from Positive Experiences. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, S79–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; O’Connor, M.; Mensah, F.; Olsson, C.A.; Goldfeld, S.; Lacey, R.E.; Slopen, N.; Thurber, K.A.; Priest, N. Measuring Positive Childhood Experiences: Testing the Structural and Predictive Validity of the Health Outcomes from Positive Experiences (HOPE) Framework. Acad. Pediatr. 2022, 22, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sege, R.; Swedo, E.A.; Burstein, D.; Aslam, M.V.; Jones, J.; Bethell, C.; Niolon, P.H. Prevalence of Positive Childhood Experiences Among Adults—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Four States, 2015–2021. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Țepordei, A.M.; Zancu, A.S.; Diaconu-Gherasim, L.R.; Crumpei-Tanasă, I.; Măirean, C.; Sălăvăstru, D.; Labăr, A.V. Children’s peer relationships, well-being, and academic achievement: The mediating role of academic competence. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1174127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Ma, T.; Deng, Y. School climate and adolescents’ prosocial behavior: The mediating role of perceived social support and resilience. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1095566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raniti, M.; Rakesh, D.; Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M. The role of school connectedness in the prevention of youth depression and anxiety: A systematic review with youth consultation. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddow, S.; Taylor, E.P.; Schwannauer, M. Positive peer relationships, coping and resilience in young people in alternative care: A systematic review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 122, 105861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.A. Resiliency Theory: A Strengths-Based Approach to Research and Practice for Adolescent Health. Health Educ. Behav. 2013, 40, 381–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Busching, R.; Krahé, B. With a Little Help from Their Peers: The Impact of Classmates on Adolescents’ Development of Prosocial Behavior. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 1849–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M.; Almerigi, J.B.; Theokas, C.; Lerner, J.V. Positive Youth Development A View of the Issues. J. Early Adolesc. 2005, 25, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boys & Girls Clubs of Monmouth County. Asbury Park Unit. Available online: https://bgcmonmouth.org/locations/asbury-park/ (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- News, U.S. Asbury Park School District. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/education/k12/new-jersey/districts/asbury-park-school-district-110351 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Azungah, T. Qualitative research: Deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qual. Res. J. 2018, 18, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birt, L.; Scott, S.; Cavers, D.; Campbell, C.; Walter, F. Member Checking: A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation? Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASEL. What is the CASEL Framework? Available online: https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/what-is-the-casel-framework/ (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Butler, N.; Quigg, Z.; Bates, R.; Jones, L.; Ashworth, E.; Gowland, S.; Jones, M. The Contributing Role of Family, School, and Peer Supportive Relationships in Protecting the Mental Wellbeing of Children and Adolescents. Sch. Ment. Health 2022, 14, 776–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, H.; Lv, Y.; Xie, D. The influence of children’s emotional comprehension on peer conflict resolution strategies. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1142373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Data Source | Project Phase | Key Results |

|---|---|---|

| DADs * (Staff) | Pre-intervention |

|

| Staff focus groups | Pre-intervention |

|

| Member focus groups | Pre-intervention |

|

| Staff observations | Pre-intervention |

|

| Staff focus group | Post-intervention |

|

| Member focus groups | Post-intervention |

|

| Member checking | Post-intervention |

|

| Category | Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship |

|

|

| Environment |

|

|

| ||

| Engagement |

|

|

| ||

| Emotional Growth |

|

|

|

|

| Category | Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship |

|

|

| ||

| Environment |

|

|

| Engagement |

|

|

| ||

| Emotional Growth |

|

|

| Category | Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship |

|

|

| Environment |

|

|

| Engagement |

|

|

| Emotional Growth |

|

|

| ||

| ||

|

| Category | Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship |

|

|

| ||

| ||

| Environment |

|

|

| ||

| Engagement |

|

|

| ||

| ||

| Emotional Growth |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gallant, L.; Borges, C.; De Lorenzo, A.; Lindberg, C.; Burstein, D. Improving Peer Relationships Through Positive Deviance Practices and the HOPE (Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences) Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101550

Gallant L, Borges C, De Lorenzo A, Lindberg C, Burstein D. Improving Peer Relationships Through Positive Deviance Practices and the HOPE (Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences) Framework. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101550

Chicago/Turabian StyleGallant, Laura, Catalina Borges, Alisha De Lorenzo, Curt Lindberg, and Dina Burstein. 2025. "Improving Peer Relationships Through Positive Deviance Practices and the HOPE (Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences) Framework" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101550

APA StyleGallant, L., Borges, C., De Lorenzo, A., Lindberg, C., & Burstein, D. (2025). Improving Peer Relationships Through Positive Deviance Practices and the HOPE (Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences) Framework. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101550