Occupational Pesticide Exposure Risks and Gendered Experiences Among Women in Horticultural Farms in Northern Tanzania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

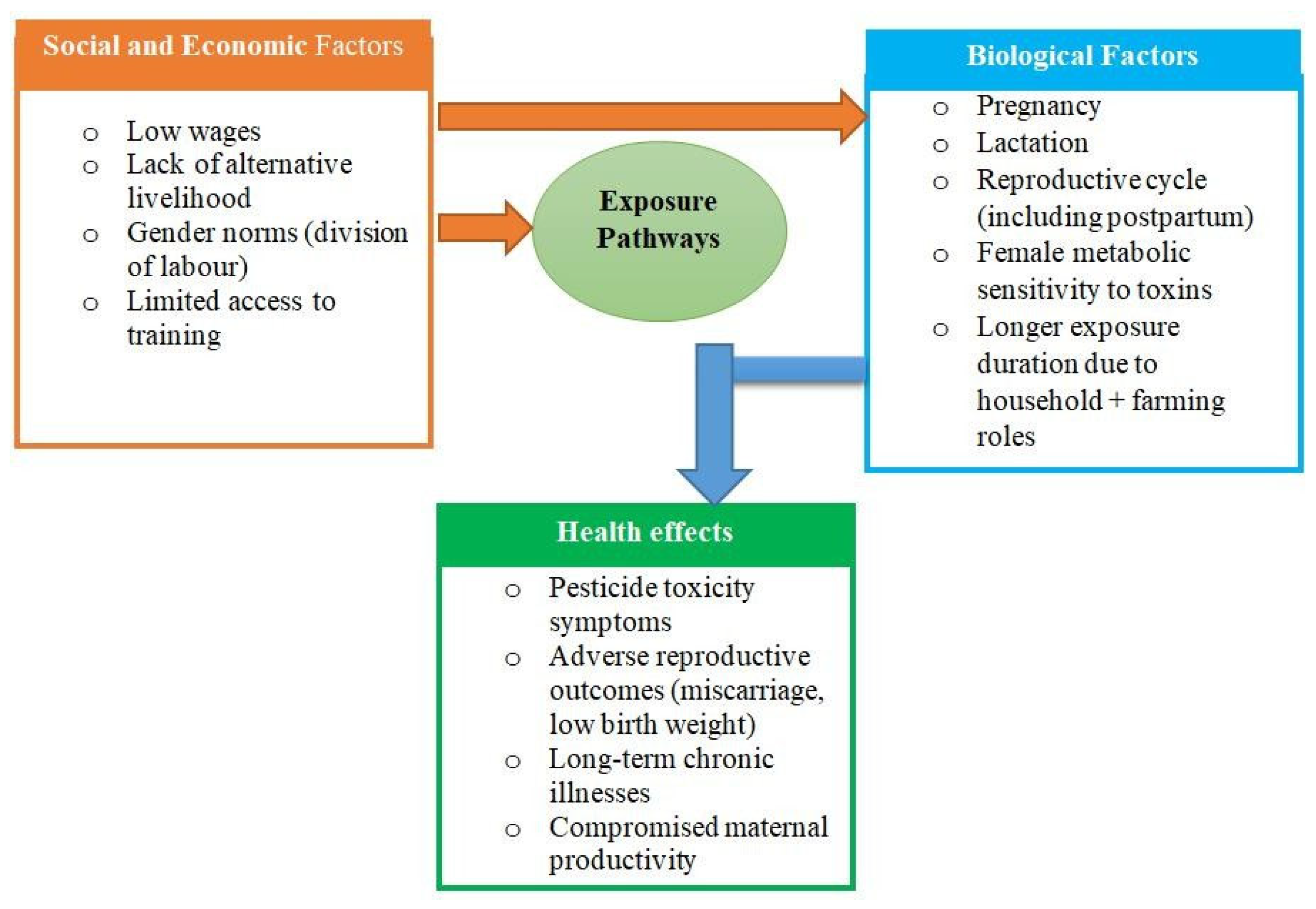

2.1. Theoretical Framework

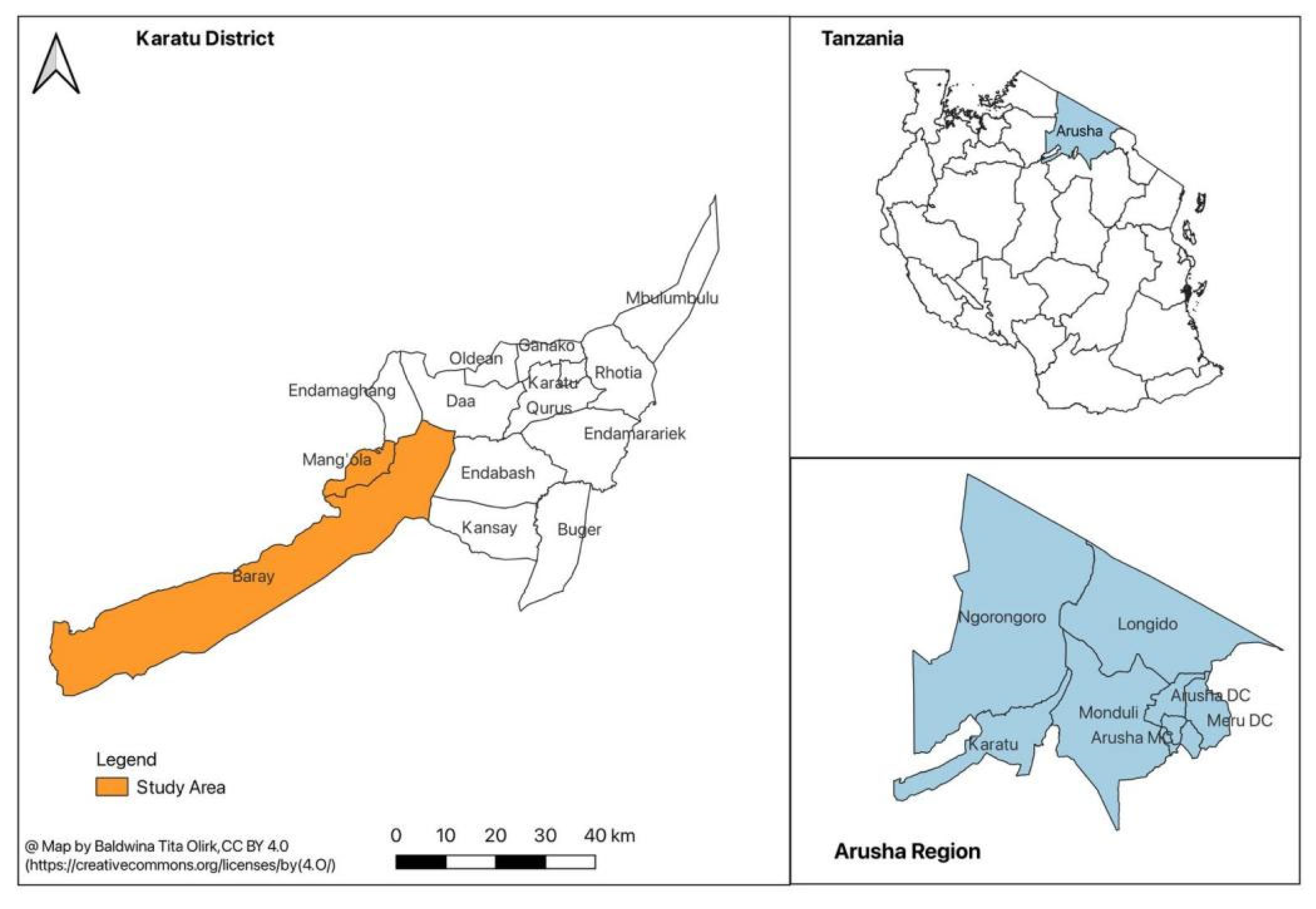

2.2. Study Design and Settings

2.3. Recruitment of Study Participants and Sample Size

2.4. Data Collection Tools

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Trustworthiness of the Findings

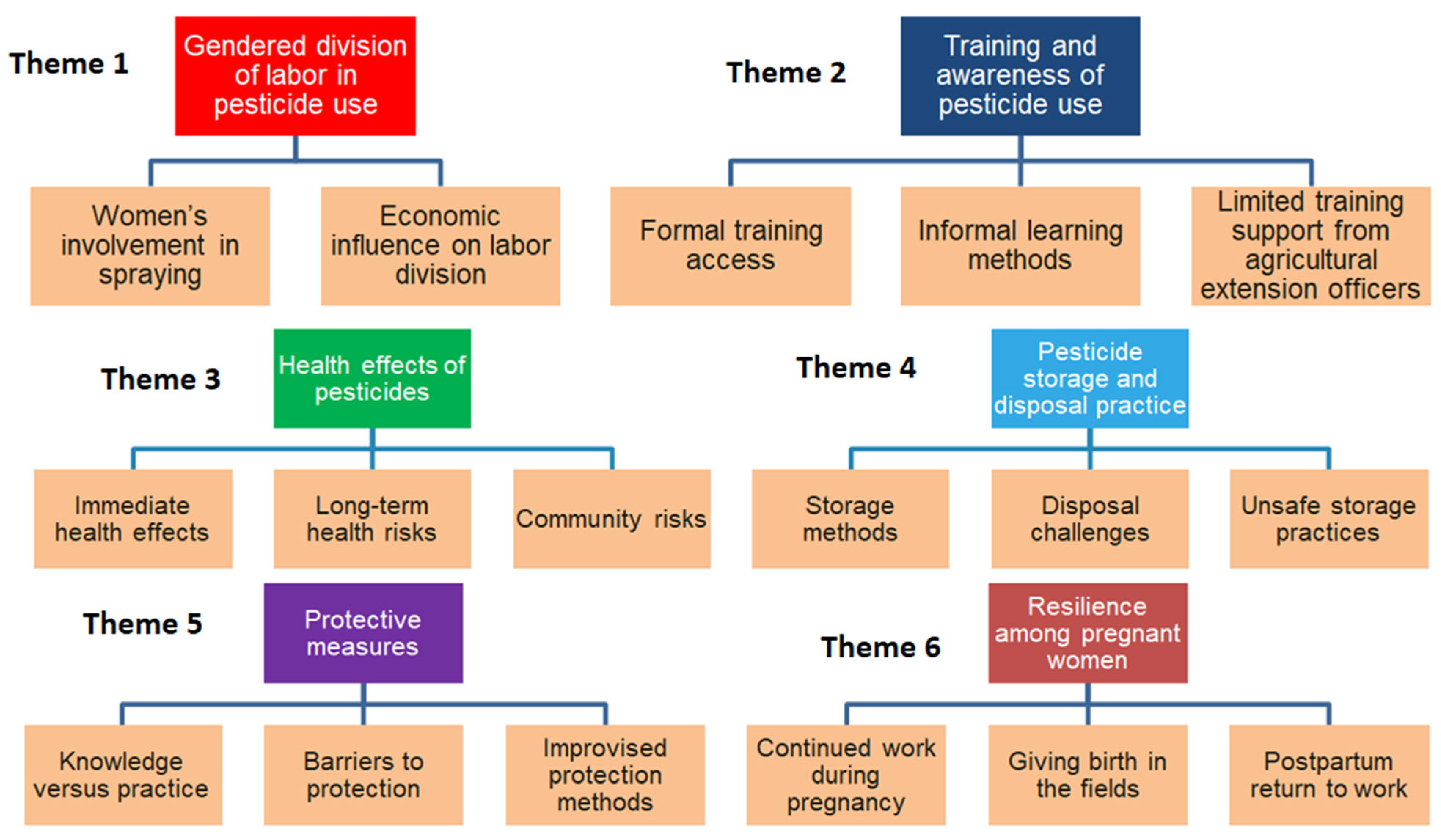

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Theme 1: Gendered Division of Labor in Pesticide Use

- (Participant, 42 years)

- “For our village, even women spray pesticides. If she’s single and lacks money to hire people to help her, then she must carry the pump herself.”

3.3. Theme 2: Training and Awareness of Pesticide Use

- (Participant, 47 years)

- “There is no class training, but you may get knowledge when you buy pesticides and read instructions on the bottle.”

- (Participant, 31 years)

- “We didn’t get training, but some of us try our best to follow the instructions provided on bottles.” Similarly, one participant added “No! We haven’t received any training, but we use pesticides simply to protect our crops.”

3.4. Theme 3: Health Effects of Pesticides

- (Participant, 28 years)

- “Some people get blood cancer or throat cancer... Pregnant women have delivered dead babies.”

- (Participant, 53 years)

- “We normally experience effects on our bodies, such as itching, abdominal discomfort, chest tightness, persistent coughing, and severe flu that doesn’t heal easily.”

3.5. Theme 4: Pesticide Storage and Disposal Practices

- (Participant, 48 years)

- “Many people buy pesticides from the shop and take them straight to the farm. In our village, we put pesticides in a small bag and hang them on the roof where children cannot reach. Honestly, everyone has their way of storing pesticides, whether in a storage room or elsewhere.”

- (Participant, 35 years)

- “You have to keep your bottles somewhere and decide what to do with them. If you choose to burn them, that’s up to you. There’s no designated dumping site for disposal, so everyone keeps them based on their convenience.”

3.6. Theme 5: Personal Protective Equipment

- (Participant, 51 years)

- “We rarely use protection because of lack of money to buy equipment.”

3.7. Theme 6: Resilience Among Pregnant Women

- (Participant, 29 years)

- “A pregnant woman must work to buy food and children’s needs. She works until she cannot anymore, sometimes until delivery.” Some of the participants mentioned that some pregnant women will continue to perform light activities like cutting onions “For tasks that are not too difficult for us, like cutting onions, we sit down, stretch legs, and continue to portion the onions.”

- (Participant, 47 years)

- “In our area, when a woman is pregnant, she continues to work until she gives birth. There is no option to stop any job; she carries out tasks like cleaning or removing weeds, regardless of whether the crops have been treated with pesticides.”

- (Participant, 45 years)

- “One day, as I was passing by, I saw a pregnant woman working in the fields. When I returned, I found her surrounded by other women, in labour. They quickly rushed her to the hospital.”

- (Participant, 40 years)

- “Those of us who don’t have a partner or are unmarried have no one to support us during pregnancy or after childbirth. So, just a few weeks after giving birth, we must wake up early around 6 a.m.to go to the farm and work to earn money for our daily needs. In the evening, we may be paid two or three thousand shillings, which we use to buy necessities for our children.”

- (Participant, 43 years)

- “Even after giving birth, the break is usually just two months. It depends on whether you have food to provide for yourself. What else can you do? You have to get back to work. For me, I only took two weeks off and was back in the fields by the third week.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COREQ | Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research |

| FGDs | Focus group discussions |

| GAD | Gender and development |

| PI | Principal investigator |

| PPE | Personal protective equipment |

References

- International Labour Office. Safety and Health in Agriculture; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; p. 5. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40ed_dialogue/%40sector/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_161135.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Negatu, B.; Kromhout, H.; Mekonnen, Y.; Vermeulen, R. Use of chemical pesticides in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional comparative study on knowledge, attitude and practice of farmers and farm workers in three farming systems. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2016, 60, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The State of Food Insecurity in the World: Addressing Food Insecurity in Protracted Crises—Key Messages; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010; p. 47. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/i1683e/i1683e.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Asmare, B.A.; Freyer, B.; Bingen, J. Women in agriculture: Pathways of pesticide exposure, potential health risks and vulnerability in sub-Saharan Africa. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2022, 34, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Isgren, E. Gambling in the garden: Pesticide use and risk exposure in Ugandan smallholder farming. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rother, H. Researching pesticide risk communication efficacy for South African farm workers. Occup. Health S. Afr. 2005, 11, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rother, H.-A. Falling through the regulatory cracks: Street selling of pesticides and poisoning among urban youth in South Africa. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2010, 16, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, S.; London, L.; Rother, H.A.; Burdorf, A.; Naidoo, R.N.; Kromhout, H. Pesticide safety training and practices in women working in small-scale agriculture in South Africa. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 67, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, M.E.; Van Houweling, E.; Zseleczky, L. Mapping gendered pest management knowledge, practices, and pesticide exposure pathways in Ghana and Mali. Agric. Human Values 2015, 32, 761–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrema, E.J.; Ngowi, A.V.; Kishinhi, S.S.; Mamuya, S.H. Pesticide exposure and health problems among female horticulture workers in Tanzania. Environ. Health Insights 2017, 11, 1178630217715237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raanan, R.; Balmes, J.R.; Harley, K.G.; Gunier, R.B.; Magzamen, S.; Bradman, A.; Eskenazi, B. Decreased lung function in 7-year-old children with early-life organophosphate exposure. Thorax 2016, 71, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikankuba, V.L.; Mwanyika, G.; Ntwenya, J.E.; James, A. Pesticide regulations and their malpractice implications on food and environment safety. Cogent Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1601544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekei, E.; Ngowi, A.V.; Mkalanga, H.; London, L. Knowledge and practices relating to acute pesticide poisoning among health care providers in selected regions of Tanzania. Environ. Health Insights 2017, 11, 1178630217691268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochago, R. Gender and pest management: Constraints to integrated pest management uptake among smallholder coffee farmers in Uganda. Cogent Food Agric. 2018, 4, 1540093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, S.; London, L.; Burdorf, A.; Naidoo, R.N.; Kromhout, H. Agricultural activities, pesticide useand occupational hazards among women working in small scale farming in Northern Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Occup. Environ. Health 2010, 14, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zseleczky, L.; Christie, M.E.; Haleegoah, J. Embodied livelihoods and tomato farmers’ gendered experience of pesticides in Tuobodom, Ghana. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2014, 18, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimbiri, P.F.; Moturi, W.N.; Sawe, J.; Henley, P.; Bend, J.R. Health impact of pesticides on residents and horticultural workers in the Lake Naivasha region, Kenya. Occup. Dis. Environ. Med. 2015, 3, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shentema, M.G.; Kumie, A.; Bråtveit, M.; Deressa, W.; Ngowi, A.V.; Moen, B.E. Pesticide use and serum acetylcholinesterase levels among flower farm workers in Ethiopia—A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonen, S.; Ambelu, A.; Wondafrash, M.; Kolsteren, P.; Spanoghe, P. Exposure of infants to organochlorine pesticides from breast milk consumption in southwestern Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitworth, K.W.; Bornman, R.M.S.; Archer, J.I.; Kudumu, M.O.; Travlos, G.S.; Wilson, R.E.; Longnecker, M.P. Predictors of plasma DDT and DDE concentrations among women exposed to indoor residual spraying for malaria control in the South African study of women and babies (SOWB). Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwanga, H.H.; Dalvie, M.A.; Singh, T.S.; Channa, K.; Jeebhay, M.F. Relationship between pesticide metabolites, cytokine patterns, and asthma-related outcomes in rural women workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2016, 13, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwakalasya, W.N.; Ruano, A.L.; Mamuya, S.H.; Moen, B.E.; Ngowi, A.V. Pregnancy, childcare, and pesticides: Understanding the health risks of women and children in small-scale horticulture in Tanzania. Qual. Health Res. 2025, 13, 10497323251342176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olirk, B.T.; Mamuya, S.H.; Tjalvin, G.; Moen, B.E.; Ngowi, A.V. Umbilical cord plasma cholinesterase activity and birth weight in babies delivered by mothers engaged in horticulture activities in Northern Tanzania. Occup. Environ. Med. 2024, 82 (Suppl. S1), A25.3. Available online: https://oem.bmj.com/content/82/Suppl_1/A25.3 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Bliznashka, L.; Roy, A.; Christiani, D.C.; Calafat, A.M.; Ospina, M.; Diao, N.; Mazumdar, M.; Jaacks, L.M. Pregnancy pesticide exposure and child development in low- and middle-income countries: A prospective analysis of a birth cohort in rural Bangladesh and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, C.F. Gender development, theories of. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative, 4th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kilic, S. Kappa test. J. Mood Disord. 2015, 5, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cypress, B.S. Rigor or reliability and validity in qualitative research: Perspectives, strategies, reconceptualization, and recommendations. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2017, 36, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.; Bryant, J.M.; Farber, D.H.; Amram, O.; Sabel, J.C. Pesticide exposure estimation across census tracts in Washington State: Identifying vulnerable areas and populations. Environ. Health Perspect. 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starbuck, A.; White, R. Living in the Shadow of Danger: Poverty, Race, and Unequal Chemical Facility Hazards. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291356761_Living_in_the_Shadow_of_Danger_Poverty_Race_and_Unequal_Chemical_Facility_Hazards (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- London, L.; De Grosbois, S.; Wesseling, C.; Kisting, S.; Rother, H.A.; Mergler, D. Pesticide usage and health consequences for women in developing countries: Out of sight, out of mind? Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2002, 8, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buralli, R.; Nazli, S.N.; Cordoba, L.; Quiros-Alcala, L.; Hyland, C.; Muñoz-Quezada, M.T.; Farías, P.; Handal, A.J. Children’s environmental and occupational exposures to pesticides in low- and middle-income countries rural areas—An elephant in the room. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 990, 179887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngowi, A.V.F.; Semali, I. Controlling pesticide poisoning at community level in Lake Eyasi Basin, Karatu District, Tanzania. Afr. Newsl. Occup. Health Saf. 2011, 16, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Sapbamrer, R.; Thammachai, A. Factors affecting use of personal protective equipment and pesticide safety practices: A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2020, 185, 109444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koussé, J.N.D.; Ilboudo, S.; Ouédraogo, J.C.R.P.; Hunsmann, M.; Ouédraogo, G.G.; Ouédraogo, M.; Kini, F.B.; Ouédraogo, S. Self-reported health effects of pesticides among cotton farmers from the Central-West region in Burkina Faso. Toxicol. Rep. 2023, 11, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESCO in Action for Gender Equality 2022–2023; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/unesco-action-gender-equality-2022-2023 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Fair Share for Health and Care: Gender and the Undervaluation of Health and Care Work; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240082854 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

| Question | |

|---|---|

| 1 | What are the main crops mostly grown in your village? |

| 2 | In agriculture, what are the different roles of men and women? Who allocated these roles? |

| 3 | What are the different roles of men and women regarding the use of pesticides in agriculture? |

| 4 | When pesticides are stored at home, where do you usually keep them? |

| 5 | Which agriculture roles do women continue doing during pregnancy? Do they have contact with pesticides? |

| 6 | At which stage of pregnancy does pregnant women get reduced roles in the farms and why? |

| 7 | Based on your experience, how long does it take from delivery to returning to the farms? What are the criteria used? |

| 8 | Who have taught you about pesticides and health effects? |

| 9 | How do you protect yourself from exposure to pesticides? |

| Character | Frequency (%) | Mean (SD, Range) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 39 (12.8, 18–74) | |

| 18–29 | 13 (28.3) | |

| 30–41 | 14 (30.4) | |

| >41 | 19 (41.3) | |

| Years of work experience | 10 (3.8, 1–35) | |

| Education level | ||

| Primary school | 37 (80) | |

| Secondary and advanced education | 9 (20) | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 14 (30) | |

| Married | 32 (70) |

| Keywords | FGD 1 | FGD 2 | FGD 3 | FGD 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men spray pesticides |  |  |  |  |

| Washing clothes/equipment |  |  |  |  |

| Weeding |  |  |  |  |

| Harvesting |  |  |  |  |

| Spray if not married |  |  |  |  |

| Carrying pesticide |  |  |  |  |

| Domestic spraying |  |  |  |  |

| Digging while pregnant |  |  |  |  |

| Harvesting while pregnant |  |  |  |  |

| Return soon after birth |  |  |  |  |

| No training |  |  |  |  |

| Learn from others |  |  |  |  |

| Extension officer |  |  |  |  |

| Store pesticides in the kitchen |  |  |  |  |

| Store pesticides under the bed |  |  |  |  |

| Hanging pesticides at the roof top |  |  |  |  |

| Throwing containers in the farms |  |  |  |  |

| Burning pesticides containers |  |  |  |  |

| Gloves |  |  |  |  |

| No protection |  |  |  |  |

| Improvized protection (cloth, scarf) |  |  |  |  |

| Low pay/no choice |  |  |  |  |

| No choice/we must eat |  |  |  |  |

| School fees |  |  |  |  |

| Headache |  |  |  |  |

| Coughing/Chest pain |  |  |  |  |

| Cancer |  |  |  |  |

| Skin itching/rash |  |  |  |  |

| Children affected |  |  |  |  |

| Dizziness |  |  |  |  |

| Miscarriage |  |  |  |  |

| Theme | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Gendered division of labor in pesticide use | Women’s involvement in spraying; Economic influence on labor division |

| Training and awareness of pesticide use | Formal training access; Informal learning methods; Limited training support from agricultural extension officers |

| Health effects of pesticides | Immediate health effects; Long-term health risks; Community risks |

| Pesticide storage and disposal practice | Storage methods; Disposal challenges; Unsafe storage practices |

| Protective measures | Knowledge versus practice; Barriers to protection; Improvied protection methods |

| Resilience among pregnant women | Continued work during pregnancy; Giving birth in the fields; Postpartum return to work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olirk, B.; Mamuya, S.; Mosha, I.; Moen, B.E.; Ngowi, A. Occupational Pesticide Exposure Risks and Gendered Experiences Among Women in Horticultural Farms in Northern Tanzania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101529

Olirk B, Mamuya S, Mosha I, Moen BE, Ngowi A. Occupational Pesticide Exposure Risks and Gendered Experiences Among Women in Horticultural Farms in Northern Tanzania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101529

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlirk, Baldwina, Simon Mamuya, Idda Mosha, Bente Elisabeth Moen, and Aiwerasia Ngowi. 2025. "Occupational Pesticide Exposure Risks and Gendered Experiences Among Women in Horticultural Farms in Northern Tanzania" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101529

APA StyleOlirk, B., Mamuya, S., Mosha, I., Moen, B. E., & Ngowi, A. (2025). Occupational Pesticide Exposure Risks and Gendered Experiences Among Women in Horticultural Farms in Northern Tanzania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101529