Analysis of the Dual Use of Electronic Cigarettes and Conventional Tobacco According to the Survey on Alcohol and Other Drugs in the General Population in Spain (EDADES 2022)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Variables

- ▪

- Dual use was defined as individuals who use ECs and smoke tobacco, either daily and/or within the past 30 days.

- ▪

- Conventional tobacco use was defined as smoking traditional tobacco products (either conventional cigarettes and/or hand-rolled tobacco) daily and/or within the past 30 days (Table S2).

- ▪

- EC use was defined as daily consumption and/or use within the past 30 days.

- ▪

- Sex (male/female).

- ▪

- Age (in years and grouped in three: 15–25, 26–50, 51–65).

- ▪

- Educational level (no education/primary, secondary, mid-level university students, upper-level university students).

- ▪

- Employment status (working, no economic activity, retired, studying).

- ▪

- Income level (≤EUR 999; EUR 1000–1499; EUR 1500–2499; EUR 2500–2999; ≥3000 or more).

- ▪

- Perceived health status: very good/good, average, and bad/very bad.

- ▪

- Self-perceived risk of tobacco consumption or EC use: few or no problems, several or many problems.

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence and Characteristics of Dual Consumers

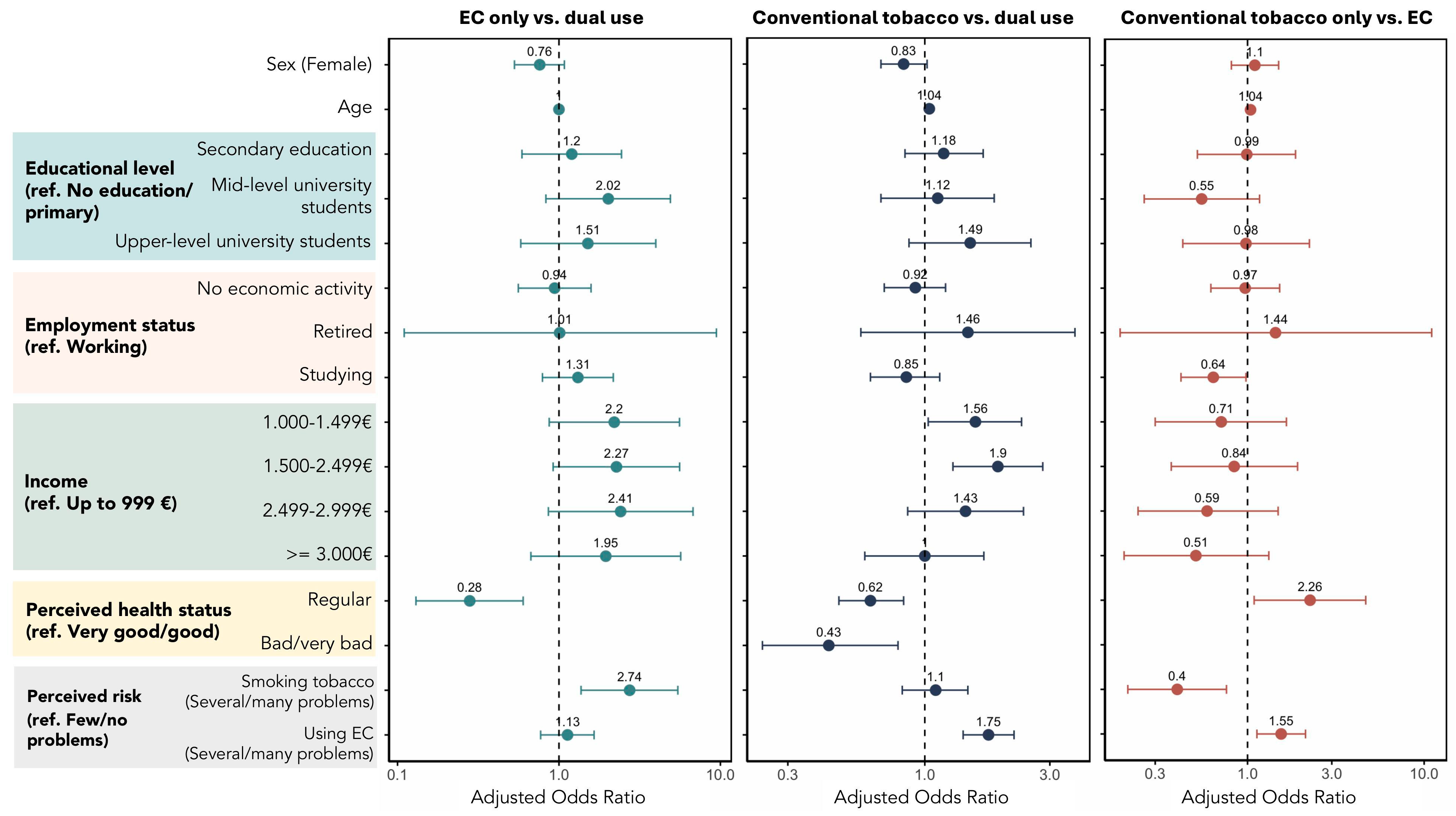

3.2. Impact of Factors Associated with EC Use and Dual Use (Figure 1, Table S4)

3.3. Changes in E-Cigarette Smokers

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Pre-Existing Literature

4.2. Strengths and Limitations:

4.3. Implications

4.4. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EC | Electronic cigarette |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| NHS | National Health Surveys |

| FCTC | Framework Convention on Tobacco Control |

| EDADES | Survey on Alcohol and Other Drugs in the General Population in Spain |

| DGPNSD | Government Delegation for the National Drug Plan |

References

- Drope, J.; Hamill, S.; Chaloupka, F.; Guerrero, C.; Lee, H.M.; Mirza, M.; Mouton, A.; Murukutla, N.; Ngo, A.; Perl, R.; et al. The Tobacco Atlas; Vital Strategies and Tobacconomics: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Montes Martínez, A.; Pérez-Ríos, M.; Ortiz, C.; Gtt-See Galán Labaca, I. Cambios en el abandono del consumo de tabaco en España, 1987–2020. Med. Clínica 2023, 160, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DE ESPAÑA JCIR. Ley 28/2005, de 26 de Diciembre, de Medidas Sanitarias Frente al Tabaquismo y Reguladora de la Venta, el Suministro, el Consumo y la Publicidad de Los Productos del Tabaco. (BOE 27/12/2005) Actualizada Ley 42/2010, de 30 de Diciembre. 2005. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2005/12/26/28/con/20101231 (accessed on 17 June 2013).

- de España, G. Ley 42/2010, de 30 de Diciembre, Por la Que se Modifica la Ley 28/2005, de 26 de Diciembre, de Medidas Sanitarias Frente al Tabaquismo y Reguladora de la Venta, el Suministro, el Consumo y la Publicidad de Los Productos del Tabaco BOE. 2010. Available online: http://www.judicatura.com/Legislacion/3477.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2013).

- Córdoba-García, R. Catorce años de ley de control del tabaco en España. Situación actual y propuestas. Atención Primaria 2020, 52, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Encuesta de Salud de España (ESdE) 2023: Nota Técnica. Principales Resultados Ministerio de Sanidad. 2025. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/encuestaSaludEspana/ESdE2023/ESdE2023_notatecnica.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Secretaría General de Salud Digital, Información, e Innovación del SNS, Subdirección General de Información Sanitaria. Encuesta Europea de Salud en España (EESE 2020); Ministerio De Sanidad Centro De Publicaciones: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas. Ministerio de Sanidad. EDADES 2024. In Encuesta Sobre Alcohol y Otras Drogas en España (EDADES) 1995–2024; Ministerio de Sanidad: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas. Ministerio de Sanidad. ESTUDES 2023. In Encuesta Sobre Uso de Drogas en Enseñanzas Secundarias en España (ESTUDES). 1994–2023; Ministerio de Sanidad: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes of Europeans Towards Tobacco and Related Products-Junio 2024—Eurobarometer Survey. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2995 (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Jerzyński, T.; Stimson, G.V. Estimation of the global number of vapers: 82 million worldwide in 2021. DHS 2023, 24, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindson, N.; Butler, A.R.; McRobbie, H.; Bullen, C.; Hajek, P.; Wu, A.D.; Begh, R.; Theodoulou, A.; Notley, C.; Rigotti, N.A.; et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 2025, CD010216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkhoran, S.; Glantz, S.A. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.J.; Bhadriraju, S.; Glantz, S.A. E-Cigarette Use and Adult Cigarette Smoking Cessation: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, B.; Tseng, T.Y.; Hardesty, J.J.; Czaplicki, L.; Cohen, J.E. Beneficial and Harmful Tobacco-Use Transitions Associated with ENDS in the U.S. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2025, 68, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, K.M.; Fetterman, J.L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bhatnagar, A.; Barrington-Trimis, J.L.; Leventhal, A.M.; Stokes, A. Association of Electronic Cigarette Use with Subsequent Initiation of Tobacco Cigarettes in US Youths. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e187794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, P.; McRobbie, H.; Bullen, C. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ta, Y.; Bhowmik, A.; José, R.J. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana-Barrios, M.A.; Payne, D.; Nugent, K. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkhoran, S.; Glantz, S.A. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation—Authors’ reply. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, e26–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Brown, J.; Buss, V.; Shahab, L. Prevalence of Popular Smoking Cessation Aids in England and Associations with Quit Success. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2454962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasza, K.A.; Edwards, K.C.; Kimmel, H.L.; Anesetti-Rothermel, A.; Cummings, K.M.; Niaura, R.S.; Sharma, A.; Ellis, E.M.; Jackson, R.; Blanco, C.; et al. Association of e-Cigarette Use with Discontinuation of Cigarette Smoking Among Adult Smokers Who Were Initially Never Planning to Quit. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2140880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasza, K.A.; Tang, Z.; Seo, Y.S.; Benson, A.F.; Creamer, M.R.; Edwards, K.C.; Everard, C.; Chang, J.T.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Das, B.; et al. Divergence in Cigarette Discontinuation Rates by Use of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS): Longitudinal Findings From the United States PATH Study Waves 1–6. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2025, 27, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.T.; Warner, K.E.; Cummings, K.M.; Hammond, D.; Kuo, C.; Fong, G.T.; Thrasher, J.F.; Goniewicz, M.L.; Borland, R. Examining the relationship of vaping to smoking initiation among US youth and young adults: A reality check. Tob. Control 2019, 28, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golder, S.; Hartwell, G.; Barnett, L.M.; Nash, S.G.; Petticrew, M.; Glover, R.E. Vaping and harm in young people: Umbrella review. Tob. Control 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begh, R.; Conde, M.; Fanshawe, T.R.; Kneale, D.; Shahab, L.; Zhu, S.; Pesko, M.; Livingstone-Banks, J.; Lindson, N.; Rigotti, N.A.; et al. Electronic cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking in young people: A systematic review. Addiction 2025, 120, 1090–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco-Pardo, M.; Candal-Pedreira, C.; García, G.; Pérez-Ríos, M.; Mourino, N.; Varela-Lema, L.; Ruano-Ravina, A.; Rey-Brandariz, J. Razones por las que los consumidores duales de cigarrillo electrónico y tabaco convencional inician o mantienen el consumo dual. Una revisión sistemática. Adicciones 2024, 37, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallus, S.; Lugo, A.; Stival, C.; Cerrai, S.; Clancy, L.; Filippidis, F.T.; Gorini, G.; Lopez, M.J.; López-Nicolás, Á.; Molinaro, S.; et al. Electronic Cigarette Use in 12 European Countries: Results from the TackSHS Survey. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 33, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Cox, S.; Shahab, L.; Brown, J. Trends and patterns of dual use of combustible tobacco and e-cigarettes among adults in England: A population study, 2016–2024. Addiction 2025, 120, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, A.; Sanchez, S.; Seth, S.; Feore, A.; Sutton, M.; Sachdeva, K.; Abu-Zarour, N.; Chaiton, M.; Schwartz, R. Evidence update on e-cigarette dependence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict. Behav. 2025, 163, 108243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisinger, C.; Rasmussen, S.K.B. The Health Effects of Real-World Dual Use of Electronic and Conventional Cigarettes versus the Health Effects of Exclusive Smoking of Conventional Cigarettes: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glantz, S.A.; Nguyen, N.; Oliveira Da Silva, A.L. Population-Based Disease Odds for E-Cigarettes and Dual Use versus Cigarettes. NEJM Evid. 2024, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.N.; Farsalinos, K. Comparing smoking-related disease rates from e-cigarette use with those from tobacco cigarette use: A reanalysis of a recently-published study. Harm Reduct. J. 2025, 22, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.; Fu, M.; Galán, I.; Pérez-Rios, M.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.M.; López, M.J.; Sureda, X.; Montes, A.; Fernández, E. Conflicts of interest in research on electronic cigarettes. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2018, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisinger, C.; Godtfredsen, N.; Bender, A.M. A conflict of interest is strongly associated with tobacco industry–favourable results, indicating no harm of e-cigarettes. Prev. Med. 2019, 119, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendlin, Y.H.; Vora, M.; Elias, J.; Ling, P.M. Financial Conflicts of Interest and Stance on Tobacco Harm Reduction: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas. Ministerio de Sanidad. Encuesta Sobre Alcohol y Otras Drogas en España (EDADES) 1995–2022; Ministerio de Sanidad: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Kim, J.; Lee, S.; Chun, J. An International Systematic Review of Prevalence, Risk, and Protective Factors Associated with Young People’s E-Cigarette Use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidón-Moyano, C.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.M.; Fu, M.; Ballbè, M.; Martín-Sánchez, J.C.; Fernández, E. Prevalencia y perfil de uso del cigarrillo electrónico en España (2014). Gac. Sanit. 2016, 30, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, M.; Grudziąż-Sękowska, J.; Kamińska, A.; Sękowski, K.; Wrześniewska-Wal, I.; Moczeniat, G.; Gujski, M.; Kaleta, D.; Ostrowski, J.; Pinkas, J. A 2024 nationwide cross-sectional survey to assess the prevalence of cigarette smoking, e-cigarette use and heated tobacco use in Poland. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2024, 37, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedman, L.; Backman, H.; Stridsman, C.; Bosson, J.A.; Lundbäck, M.; Lindberg, A.; Rönmark, E.; Ekerljung, L. Association of Electronic Cigarette Use With Smoking Habits, Demographic Factors, and Respiratory Symptoms. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e180789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.M.; Bowe, A.K.; Sheridan, A.; Doyle, F.; Boland, F.; Kavanagh, P. Evolution of nicotine product use in Ireland 2015–2023, and associations with quit intentions and attempts: An analysis of nationally representative repeated cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 2025, 55, 101352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, S.; Sheikhattari, P. Social Epidemiology of Dual Use of Electronic and Combustible Cigarettes Among, U.S. Adults: Insights from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Glob. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 3, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wu, J.; Xu, X.; Yin, P.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; et al. E-cigarette use among adults in China: Findings from repeated cross-sectional surveys in 2015–2016 and 2018–2019. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e639–e649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.-Y.; Paek, Y.-J.; Seo, H.G.; Cheong, Y.S.; Lee, C.M.; Park, S.M.; Lee, K. Dual use of electronic and conventional cigarettes is associated with higher cardiovascular risk factors in Korean men. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemperer, E.M.; Kock, L.; Feinstein, M.J.P.; Coleman, S.R.M.; Gaalema, D.E.; Higgins, S.T. Sex differences in tobacco use, attempts to quit smoking, and cessation among dual users of cigarettes and e-cigarettes: Longitudinal findings from the US Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Prev. Med. 2024, 185, 108024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, C.; Hugueley, B.; Cui, Y.; Nunez, D.M.; Kuo, T.; Kuo, A.A. Predictors of Dual E-Cigarette and Cigarette Use. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2022, 28, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebisi, Y.A.; Bafail, D.A.; Oni, O.E. Prevalence, demographic, socio-economic, and lifestyle factors associated with cigarette, e-cigarette, and dual use: Evidence from the 2017–2021 Scottish Health Survey. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2024, 19, 2151–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, J.; Smit, T.; Olofsson, H.; Mayorga, N.A.; Garey, L.; Zvolensky, M.J. Substance Use among Exclusive Electronic Cigarette Users and Dual Combustible Cigarette Users: Extending Work to Adult Users. Subst. Use Misuse 2021, 56, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Brown, J.; Kock, L.; Shahab, L. Prevalence and uptake of vaping among people who have quit smoking: A population study in England, 2013–2024. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aonso-Diego, G.; Secades-Villa, R.; García-Pérez, Á.; Weidberg, S.; Fernández-Hermida, J.R. Association between e-cigarette and conventional cigarette use among Spanish adolescents. Adicciones 2024, 36, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baenziger, O.N.; Ford, L.; Yazidjoglou, A.; Joshy, G.; Banks, E. E-cigarette use and combustible tobacco cigarette smoking uptake among non-smokers, including relapse in former smokers: Umbrella review, systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soneji, S.; Barrington-Trimis, J.L.; Wills, T.A.; Leventhal, A.M.; Unger, J.B.; Gibson, L.A.; Yang, J.; Primack, B.A.; Andrews, J.A.; Miech, R.A.; et al. Association Between Initial Use of e-Cigarettes and Subsequent Cigarette Smoking Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.M.; Steffensen, I.; Miguel, R.T.D.; Babic, T.; Carlone, J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between e-cigarette use among non-tobacco users and initiating smoking of combustible cigarettes. Harm Reduct. J. 2024, 21, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: The MPOWER Package; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Dual Consumer (n = 409) | EC Only (n = 183) | Tobacco Only (n = 9411) | Overall (n = 10,003) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 217 (53.1) | 109 (59.6) | 5384 (57.2) | 5710 (57.1) | 0.199 a |

| Age | 29.0 [22.0–40.0] | 26.0 [21.0–37.0] | 37.0 [27.0–48.0] | 37.0 [26.0–48.0] | <0.001 b |

| Age group | |||||

| 15–25 years | 166 (40.6) | 83 (45.4) | 2022 (21.5) | 2271 (22.7) | <0.001 a |

| 26–40 years | 141 (34.5) | 63 (34.4) | 3643 (38.7) | 3847 (38.5) | |

| 41–65 years | 102 (24.9) | 37 (20.2) | 3746 (39.8) | 3885 (38.8) | |

| Educational level | |||||

| No education/primary | 47 (11.5) | 13 (7.1) | 910 (9.7) | 970 (9.7) | 0.067 a |

| Secondary | 307 (75.1) | 132 (72.1) | 6991 (74.3) | 7430 (74.3) | |

| Mid-level university students | 31 (7.5) | 23 (12.6) | 693 (7.4) | 747 (7.5) | |

| Upper-level university students | 24 (5.9) | 14 (7.7) | 799 (8.5) | 837 (8.4) | |

| Employment status | |||||

| Working | 216 (52.8) | 99 (54.1) | 5898 (62.7) | 6213 (62.1) | <0.001 a |

| No economic activity | 94 (23.0) | 27 (14.8) | 1966 (20.9) | 2087 (20.9) | |

| Retired | 5 (1.2) | 1 (0.5) | 347 (3.7) | 353 (3.5) | |

| Studying | 89 (21.8) | 53 (29.0) | 1098 (11.7) | 1240 (12.4) | |

| Income | |||||

| Up to EUR 999 | 45 (11.0) | 7 (3.8) | 672 (7.1) | 724 (7.2) | <0.001 a |

| From EUR 1000 to 1499 | 63 (15.4) | 28 (15.3) | 1595 (16.9) | 1686 (16.9) | |

| From EUR 1500 to 2499 | 89 (21.8) | 46 (25.1) | 2913 (31.0) | 3048 (30.5) | |

| From EUR 2500 to 2999 | 29 (7.1) | 17 (9.3) | 714 (7.6) | 760 (7.6) | |

| 3000 or more | 27 (6.6) | 14 (7.7) | 493 (5.2) | 534 (5.3) | |

| Perceived health status | |||||

| Very good/good | 326 (79.7) | 175 (95.6) | 7850 (83.4) | 8351 (83.5) | <0.001 c |

| Regular | 65 (15.9) | 8 (4.4) | 1324 (14.1) | 1397 (14.0) | |

| Bad/very bad | 13 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 192 (2.0) | 205 (2.0) | |

| Perceived risk of smoking one pack of cigarettes per day | |||||

| Few or no problems | 72 (17.6) | 11 (6.0) | 1133 (12.0) | 1216 (12.2) | <0.001 c |

| Several or many problems | 333 (81.4) | 171 (93.4) | 8150 (86.6) | 8654 (86.5) | |

| Perceived risk of using EC | |||||

| Few or no problems | 204 (49.9) | 79 (43.2) | 3021 (32.1) | 3304 (33.0) | <0.001 c |

| Several or many problems | 175 (42.8) | 95 (51.9) | 5027 (53.4) | 5297 (53.0) | |

| Patterns of Use in Dual Users | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Smoked tobacco daily, used ECs in the last 30 days | 192 | 46.9 |

| Daily users of both ECs and tobacco | 149 | 36.4 |

| Used both ECs and tobacco in the last 30 days | 35 | 8.6 |

| Daily EC use, smoked tobacco in the last 30 days | 20 | 4.9 |

| Dual users, but frequency of use could not be determined | 13 | 3.2 |

| Total | 409 | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rubio-Serrano, J.; Gefaell-Larrondo, I.; Serrano-Serrano, E.; Olano-Espinosa, E.; Minué-Lorenzo, C. Analysis of the Dual Use of Electronic Cigarettes and Conventional Tobacco According to the Survey on Alcohol and Other Drugs in the General Population in Spain (EDADES 2022). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101507

Rubio-Serrano J, Gefaell-Larrondo I, Serrano-Serrano E, Olano-Espinosa E, Minué-Lorenzo C. Analysis of the Dual Use of Electronic Cigarettes and Conventional Tobacco According to the Survey on Alcohol and Other Drugs in the General Population in Spain (EDADES 2022). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101507

Chicago/Turabian StyleRubio-Serrano, Javier, Ileana Gefaell-Larrondo, Encarnación Serrano-Serrano, Eduardo Olano-Espinosa, and César Minué-Lorenzo. 2025. "Analysis of the Dual Use of Electronic Cigarettes and Conventional Tobacco According to the Survey on Alcohol and Other Drugs in the General Population in Spain (EDADES 2022)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101507

APA StyleRubio-Serrano, J., Gefaell-Larrondo, I., Serrano-Serrano, E., Olano-Espinosa, E., & Minué-Lorenzo, C. (2025). Analysis of the Dual Use of Electronic Cigarettes and Conventional Tobacco According to the Survey on Alcohol and Other Drugs in the General Population in Spain (EDADES 2022). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101507