Health Perceptions and Trust in Healthcare After COVID-19: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Survey from Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Size and Sampling Method

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description—Sociodemographic Profile

3.2. Health Behavior Patterns

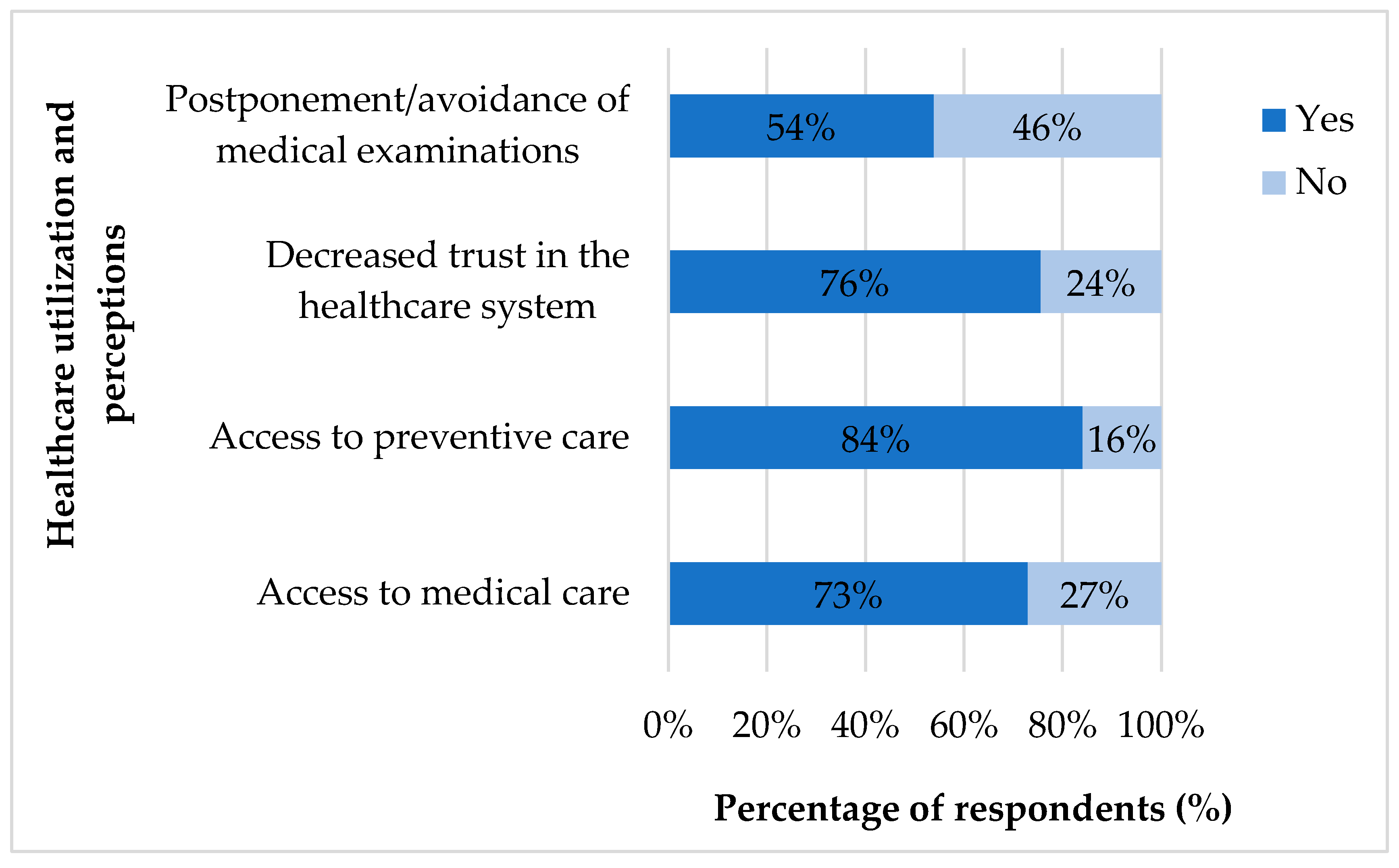

3.3. Indirect Impact of the Pandemic

3.4. Association Between Sociodemographic and Behavioral Factors and Perceived Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Lifestyle Risks

4.2. Mental Health Outcomes

4.3. Trust Loss and Access to Health Care

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| χ2 | Chi-Square |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| df | Degrees of Freedom |

| EU | European Union |

| GP | General Practitioner |

| LE | Life Expectancy |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Ortiz-Ospina, E. Life Expectancy—What Does This Actually Mean? Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy-how-is-it-calculated-and-how-should-it-be-interpreted (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Eurostat. Mortality and Life Expectancy Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Mortality_and_life_expectancy_statistics (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Kontis, V.; Bennett, J.E.; Rashid, T.; Parks, R.M.; Pearson-Stuttard, J.; Guillot, M.; Asaria, P.; Zhou, B.; Battaglini, M.; Corsetti, G.; et al. Magnitude, demographics and dynamics of the effect of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on all-cause mortality across 21 industrialized countries. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1919–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heuveline, P. Global and National declines in life expectancy: An end-of-2021 assessment. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2022, 48, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisie, V.; Ciobanu, A.M.; Moisa, E.; Manea, M.C.; Puiu, M.G. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on inpatient admissions for psychotic and affective disorders: The experience of a large psychiatric teaching hospital in Romania. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Militaru, A.; Armean, P.; Ghita, N.; Andrei, D.P. Barriers to healthcare access during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: A cross-sectional study among romanian patients with chronic illnesses and confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Social Report 2021: Reconsidering Rural Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 9789216040628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindegaard, N.; Benros, M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Font, J.; Vilaplana-Prieto, C. Trusting the Health System and COVID 19 Restriction Compliance. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2023, 49, 101235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Living, Working and COVID-19; COVID-19 Series; Publications office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, D.; Gaskell, J.; Jennings, W.; Stoker, G. Trust and the Coronavirus Pandemic: What are the consequences of and for trust? An early review of the literature. Polit. Stud. Rev. 2021, 19, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, A.; McBryde, E.; Adegboye, O.A. Does high public trust amplify compliance with stringent COVID-19 government health guidelines? A Multi-country analysis using data from 102,627 individuals. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- National Institute of Public Health. Analysis of the Evolution of Communicable Diseases Under Surveillance; Annual Reports 2020 și 2021; NIPH: București, Romania, 2021. Available online: https://insp.gov.ro/download/analiza-bolilor-transmisibile-aflate-in-supraveghere-raport-pentru-anul-2020-2021/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Streinu-Cercel, A.; Apostolescu, C.; Săndulescu, O.; Oțelea, D.; Streinu-Cercel, A.; Vlaicu, O.; Paraschiv, S.; Benea, O.E.; Bacruban, R.; Nițescu, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 in Romania—Analysis of the first confirmed case and evolution of the pandemic in Romania in the first three months. Germs 2020, 10, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Public Health. Analysis of the Evolution of Communicable Diseases Under Surveillance; Annual Reports 2022; NIPH: București, Romania, 2022. Available online: https://insp.gov.ro/download/analiza-bolilor-transmisibile-aflate-in-supraveghere-raport-pentru-anul-2022/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- National Institute of Public Health. Analysis of the Evolution of Communicable Diseases Under Surveillance; Annual Reports 2023; NIPH: București, Romania, 2023. Available online: https://insp.gov.ro/download/analiza-bolilor-transmisibile-aflate-in-supraveghere-raport-pentru-anul-2023/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- OECD; European Union. Health at a Glance: Europe 2022: State of Health in the EU Cycle; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dascalu, S.; Geambasu, O.; Raiu, C.V.; Popovici, E.D.; Apetrei, C. COVID-19 in Romania: What went wrong? Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 813941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popa, A.D.; Enache, A.I.; Popa, I.V.; Antoniu, S.A.; Dragomir, R.A.; Burlacu, A. Determinants of the Hesitancy toward COVID-19 Vaccination in Eastern European Countries and the Relationship with Health and Vaccine Literacy: A Literature Review. Vaccines 2022, 10, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburto, J.M.; Schöley, J.; Kashnitsky, I.; Zhang, L.; Rahal, C.; Missov, T.I.; Mills, M.C.; Dowd, J.B.; Kashyap, R. Quantifying impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic through life-expectancy losses: A population-level study of 29 countries. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 51, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Romania: Country Health Profile 2021; OECD Publishing: Paris, France; European Observatory: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Country Cancer Profile: Romania 2023; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2023/02/eu-country-cancer-profile-romania-2023_b7601b86.html (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Bărbulescu, L.N.; Rădulescu, V.-M.; Bărbulescu, L.F.; Mogoantă, S.-Ș. The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer secondary preventive healthcare measures. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinmohamed, A.G.; Visser, O.; Verhoeven, R.H.A.; Louwman, M.W.J.; van Nederveen, F.H.; Willems, S.M.; Merkx, M.A.W.; Lemmens, V.E.P.P.; Nagtegaal, I.D.; Siesling, S. Fewer cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 epidemic in the Netherlands. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 750–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, E.; Tetia, T.; Poroch, M.; Ungureanu, M.; Cosmescu, A.; Barbacariu, L.; Slanina, A.M.; Bacusca, A.; Petroae, A.; Novac, O.; et al. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: A web-based study among Romanian adults. Cureus 2022, 14, e31331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vancea, F.; Apostol, M.-Ș. Changes in mental health during the COVID-19 crisis in Romania: A repeated cross-section study based on the measurement of subjective perceptions and experiences. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 368504211025873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, J.; Bailey, S.; Lovett, R.; Batio, S. Missed Healthcare Visits during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A longitudinal study. Ann. Fam. Med. 2023, 21 (Suppl. 3), 5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaledi-Paveh, B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.R.; McGee, R.E.; Druss, B.G. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Maljichi, D.; Limani, B.; Spier, T.E.; Angjelkoska, V.; Stojković Zlatanović, S.; Maljichi, D.; Alloqi Tahirbegolli, I.; Tahirbegolli, B.; Kulanić, A.; Agolli Nasufi, I.; et al. (Dis)trust in doctors and public and private healthcare institutions in the Western Balkans. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 2015–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampetakis, L.A.; Melas, C. The health belief model predicts vaccination intentions against COVID-19: A survey experiment approach. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2021, 13, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | N (%) 423 (100%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 342 (80.8%) |

| Male | 81 (19.1%) |

| Age groups | |

| <20 years | 33 (7.8%) |

| 20–30 years | 309 (73.0%) |

| 31–45 years | 45 (10.6%) |

| 46–65 years | 30 (7.0%) |

| >65 years | 6 (1.4%) |

| Residence | |

| Urban | 127 (30.0%) |

| Rural | 296 (69.9%) |

| Education level | |

| No formal education | 5 (1.1%) |

| High school | 294 (69.5%) |

| Postsecondary nontertiary education | 11 (2.6%) |

| University studies | 91 (21.5%) |

| Postgraduate studies | 22 (5.2%) |

| Occupation | |

| Student/Pupil | 253 (59.8%) |

| Unemployed/Household | 46 (10.8%) |

| Employed | 118 (27.9%) |

| Retired | 6 (1.4%) |

| Variables | N (%) 423 (100%) |

| Smoking | |

| Yes | 20 (4.7%) |

| No | 403 (95.3%) |

| Toxic environment (workplace/home) | |

| Yes | 14 (3.3%) |

| No | 409 (96.7%) |

| Active lifestyle | |

| Yes | 367 (86.7%) |

| No | 56 (13.2%) |

| Healthy diet | |

| Yes | 360 (85.1%) |

| No | 63 (14.9%) |

| Timely healthcare seeking | |

| Yes | 343 (81.1%) |

| No | 76 (18.0%) |

| No, I do not have a GP | 4 (0.9%) |

| Medical check-up frequency | |

| >2x/year | 24 (5.7%) |

| 2x/year | 33 (7.8%) |

| 1x/year | 122 (28.8%) |

| Rarely | 244 (57.7%) |

| Medical appointment adherence | |

| Yes | 294 (69.5%) |

| No | 129 (30.5%) |

| Outcome Variables | Sociodemographic Variables | N (%) | χ2 | df | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased stress & anxiety during the pandemic | Age | 423 (100%) | 61.84 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 423 (100%) | 6.54 | 1 | 0.011 | |

| Education level | 423 (100%) | 53.41 | 4 | <0.001 | |

| Residence | 423 (100%) | 49.66 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Decreased trust in the healthcare system following the pandemic | Age | 423 (100%) | 36.48 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 423 (100%) | 5.01 | 1 | 0.025 | |

| Education level | 423 (100%) | 33.12 | 4 | <0.001 | |

| Residence | 423 (100%) | 23.41 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Perceived decrease in LE following the pandemic | Age | 423 (100%) | 49.79 | 4 | 0.001 |

| Gender | 423 (100%) | 10.79 | 1 | 0.001 | |

| Education level | 423 (100%) | 49.06 | 4 | <0.001 | |

| Residence | 423 (100%) | 16.55 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Outcome Variables | Behavioral Variables | N (%) | χ2 | df | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased stress & anxiety during the pandemic | Active lifestyle | 423 (100%) | 36.49 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 423 (100%) | 12.23 | 1 | 0.00 | |

| Toxic environment (workplace/home) | 423 (100%) | 0.36 | 1 | 0.547 | |

| Healthy diet | 423 (100%) | 75.16 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Medical check-up frequency | 423 (100%) | 49.00 | 3 | <0.001 | |

| Medical appointment adherence | 423 (100%) | 83.49 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Decreased trust in the healthcare system following the pandemic | Active lifestyle | 423 (100%) | 10.87 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 423 (100%) | 1.97 | 1 | 0.160 | |

| Toxic environment (workplace/home) | 423 (100%) | 1.75 | 1 | 0.185 | |

| Healthy diet | 423 (100%) | 5.19 | 1 | 0.023 | |

| Medical check-up frequency | 423 (100%) | 44.93 | 3 | <0.001 | |

| Medical appointment adherence | 423 (100%) | 17.68 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Perceived decrease in LE following the pandemic | Active lifestyle | 423 (100%) | 0.46 | 1 | 0.497 |

| Smoking | 423 (100%) | 0.50 | 1 | 0.481 | |

| Toxic environment (workplace/home) | 423 (100%) | 3.23 | 1 | 0.072 | |

| Healthy diet | 423 (100%) | 1.77 | 1 | 0.183 | |

| Medical check-up frequency | 423 (100%) | 11.23 | 3 | 0.011 | |

| Medical appointment adherence | 423 (100%) | 46.56 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Variable | N (%) | B | SE | Wald χ | df | p-Value | OR (ExpB) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors of Stress/Anxiety | ||||||||

| Age: 31–45 yo | 45 (10.6%) | 1.136 | 0.511 | 4.935 | 1 | 0.026 | 3.113 | [1.143–8.478] |

| Age: 46–65 yo | 30 (7.0%) | 1.560 | 0.530 | 8.673 | 1 | 0.003 | 4.758 | [1.685–13.436] |

| Age: >65 yo | 6 (1.4%) | 2.410 | 0.931 | 6.698 | 1 | 0.009 | 11.135 | [1.795–69.081] |

| Gender: Male | 81 (19.1%) | −0.968 | 0.373 | 6.738 | 1 | 0.009 | 0.380 | [0.183–0.789] |

| Residence: Urban | 127 (30.0%) | 1.023 | 0.307 | 11.129 | 1 | 0.000 | 2.781 | [1.524–5.072] |

| Healthy diet: No | 63 (14.8%) | 1.855 | 0.441 | 17.654 | 1 | <0.001 | 6.389 | [2.689–15.176] |

| Medical appointment adherence: No | 129 (30.4%) | 1.514 | 0.313 | 23.432 | 1 | <0.001 | 4.543 | [2.461–8.385] |

| Decreased Trust in Healthcare | ||||||||

| Age: <20 yo | 33 (7.8%) | −2.079 | 0.486 | 18.34 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.125 | [0.051–0.306] |

| Residence: Urban | 127 (30.02%) | −0.607 | 0.302 | 4.04 | 1 | 0.035 | 0.545 | [0.309–0.96] |

| Perceived Decrease in LE | ||||||||

| Age: <20 yo | 33 (7.8%) | −2.313 | 0.548 | 17.82 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.099 | [0.038–0.261] |

| Age: >65 yo | 6 (1.4%) | −2.163 | 0.878 | 6.08 | 1 | 0.014 | 0.115 | [0.019–0.702] |

| Ed. level: Postsec. nontertiary ed. | 11 (2.6%) | −2.554 | 1.079 | 5.61 | 1 | 0.018 | 0.078 | [0.006–0.974] |

| Ed. level: University studies | 91 (21.5%) | −2.526 | 0.978 | 6.67 | 1 | 0.010 | 0.080 | [0.009–0.688] |

| Ed. level: Postgraduate studies | 22 (5.2%) | −3.194 | 1.283 | 6.20 | 1 | 0.013 | 0.041 | [0.004–0.433] |

| Medical appointment adherence: No | 129 (30.4%) | −1.356 | 0.314 | 18.68 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.257 | [0.140–0.471] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bodea, R.; Buboacă, A.M.; Ferencz, L.I.; Ábrám, Z.; Voidăzan, T.S. Health Perceptions and Trust in Healthcare After COVID-19: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Survey from Romania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101496

Bodea R, Buboacă AM, Ferencz LI, Ábrám Z, Voidăzan TS. Health Perceptions and Trust in Healthcare After COVID-19: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Survey from Romania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101496

Chicago/Turabian StyleBodea, Réka, Alexandra Maria Buboacă, Lorand Iozsef Ferencz, Zoltán Ábrám, and Toader Septimiu Voidăzan. 2025. "Health Perceptions and Trust in Healthcare After COVID-19: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Survey from Romania" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101496

APA StyleBodea, R., Buboacă, A. M., Ferencz, L. I., Ábrám, Z., & Voidăzan, T. S. (2025). Health Perceptions and Trust in Healthcare After COVID-19: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Survey from Romania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101496