1. Introduction

Tobacco use is one of the leading preventable causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), tobacco kills more than 8 million people each year, including 1.2 million non-smokers exposed to secondhand smoke [

1]. Despite global efforts to reduce tobacco consumption through regulatory policies, taxation, and public education campaigns, smoking remains prevalent in many low- and middle-income countries, particularly among men [

2].

Indonesia ranks among the countries with the highest smoking prevalence in Southeast Asia. The 2018 Basic Health Research (Riskesdas) reported that 28.9% of the Indonesian population smokes, with 55.8% of adult males being active smokers [

3]. In the province of Aceh, the situation is even more concerning, with male smoking prevalence reaching 56.12%, placing it among the highest in the country [

4]. Cultural acceptance, weak enforcement of anti-smoking policies, and local norms that perceive smoking as part of male identity have all contributed to this public health challenge [

5].

While tobacco control policies often focus on legislative action and mass media campaigns, less attention has been paid to the role of the family unit, especially women, in influencing smoking behavior at the household level [

6]. Women, particularly wives and mothers, play a critical role in shaping family health practices. Their involvement in caregiving, health promotion, and behavioral monitoring positions them as potential agents of change in tobacco cessation efforts [

7]. However, in patriarchal and culturally conservative societies such as Aceh, gender power dynamics, religious norms, and social expectations often limit women’s ability to intervene effectively in male-dominated behaviors such as smoking [

8].

Several studies have examined social and environmental factors influencing smoking behavior. Still, there remains a lack of research exploring the active agency of women in tobacco control within traditional family systems [

9]. The current literature does not sufficiently capture the strategies, constraints, and coping mechanisms employed by women who seek to reduce smoking behaviors in their households [

10]. Furthermore, there is limited application of participatory frameworks that empower women not only as caregivers but also as community-based health advocates.

To address this gap, the present study explores the role of women in controlling the smoking behavior of family members in Aceh using a Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach. This method enables the co-construction of knowledge and community-led strategies grounded in local values and lived experiences. By doing so, this study aims to contribute to the development of more inclusive and culturally sensitive tobacco control interventions in Indonesia and similar contexts. This study makes a significant contribution to the tobacco control literature in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) by offering a contextually grounded, community-based perspective on how women in culturally and religiously conservative regions such as Aceh, Indonesia, develop household-level smoking cessation strategies. Unlike most studies that focus on macro-level policies or quantitative data, this research fills a significant knowledge gap by presenting first-hand narratives of subjective experiences and relational dynamics that shape tobacco control within the domestic sphere.

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Tobacco Use and Family Dynamics

Tobacco consumption remains a significant global public health issue, causing more than 8 million deaths annually [

11]. In low- and middle-income countries, where smoking prevalence is higher among men, exposure to secondhand smoke often disproportionately affects women and children in the household [

12]. The domestic setting becomes a critical environment for both exposure and intervention. Studies have highlighted the significant role of family dynamics in influencing smoking behaviors [

13]. Family support, particularly from spouses, has a measurable impact on smoking cessation outcomes. Their research indicates that when family members actively support quitting efforts, the likelihood of successful cessation increases [

14]. This underscores the necessity to explore the interpersonal and household context of smoking behavior beyond the individual smoker.

1.1.2. The Role of Women in Health Advocacy

Women are typically regarded as central health managers within the family, a role consistently observed in both global health discourse and local contexts, such as Indonesia, including Aceh. This positioning reflects their everyday responsibilities in ensuring household nutrition, caregiving, and health-related decision making. As caregivers, mothers, and spouses, women hold substantial influence over health-related decisions, including diet, healthcare utilization, and lifestyle habits such as smoking [

15]. In conservative or patriarchal societies, such as Aceh, this influence is often culturally embedded, although not always explicitly acknowledged [

16]. Previous studies have demonstrated the informal yet powerful authority of women in promoting smoke-free environments at home [

17]. For instance, preview research documented how women households used social persuasion and emotional appeals to alter husbands’ smoking behaviors [

18]. Similar dynamics are seen in Southeast Asia, where women act as mediators between public health messages and family-level behavioral change [

19].

1.1.3. Smoking Cessation and Family-Based Interventions

Effective smoking cessation often involves more than just individual willpower; it is also shaped by the environment in which the smoker resides. Family-based interventions have gained recognition for their potential to enhance the success of smoking cessation programs [

20]. The social pressure and emotional attachment within families were more influential than public health campaigns alone [

21]. Furthermore, interventions that include family education, particularly those targeting wives and mothers, have demonstrated improved outcomes in terms of smoking motivation and relapse prevention [

22]. Such findings emphasize the need to empower non-smoking family members, especially women, as key actors in cessation programs.

1.1.4. The PRECEDE Model as a Behavioral Framework

The PRECEDE-PROCEED model developed serves as a strategic planning framework for health promotion and behavioral interventions [

23]. The PRECEDE component (Predisposing, Reinforcing, and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation) is particularly relevant to this study, as it offers a systematic approach to identifying behavioral determinants [

24]. Predisposing factors include knowledge, beliefs, values, and attitudes that may influence readiness to change. Enabling factors refer to conditions that facilitate or hinder the change process, such as access to resources or services [

25]. Reinforcing factors include social support or feedback that sustains behavioral change, such as encouragement from religious leaders or local regulations. Numerous studies that have applied the PRECEDE model to tobacco control have found it effective in identifying barriers and mobilizing community-based strategies [

26]. Its flexibility allows for adaptation to cultural settings, making it suitable for application in Aceh.

1.1.5. Participatory Action Research (PAR) and Community Engagement

PAR is a collaborative research approach that actively involves community members in identifying problems and developing solutions [

27]. It is grounded in empowerment and co-creation of knowledge, particularly relevant when addressing behavior deeply rooted in culture and social norms [

28]. Preview research argues that PAR facilitates genuine community ownership of health programs, which leads to greater sustainability and relevance [

29]. In tobacco control, PAR enables women to share their experiences and influence interventions that reflect their realities [

30]. The other researcher demonstrated that involving women in designing smoke-free campaigns in low-income settings led to higher compliance and engagement [

31]. In the context of Aceh, PAR supports the inclusion of women not only as study participants but also as agents of transformation, bridging public health goals with cultural realities.

1.2. Conceptual Framework of Study

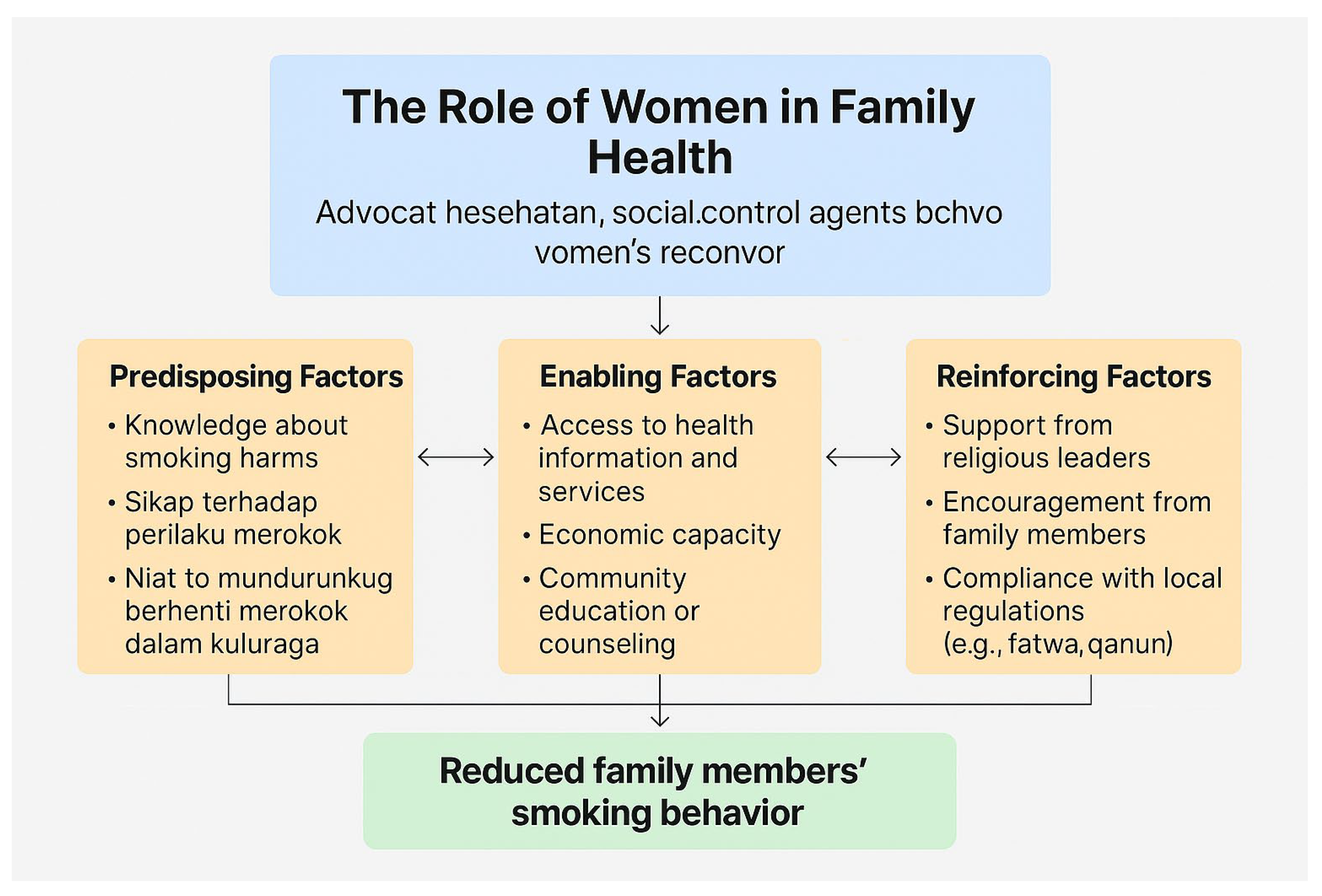

This study proposes an emergent conceptual framework based on the thematic findings described above. The framework illustrates the mechanisms through which women influence smoking behavior in the household and redefine gendered roles in health promotion.

Figure 1 highlights how women act as central agents in promoting family health by influencing behaviors related to smoking through a combination of internal motivation and external support. Their role is shaped by enabling factors, such as access to health services, economic capacity, and education, as well as by reinforcing factors like support from religious leaders and encouragement from family. When these elements align, they facilitate behavior change and lead to a decrease in smoking among family members, underscoring women’s strategic position in health advocacy within households.

1.3. Research Questions

To understand the sociocultural dynamics and participatory role of women in promoting smoking cessation within Acehnese households, this study was guided by a series of research questions rooted in the PRECEDE model (Predisposing, Enabling, Reinforcing factors). These questions were designed to explore not only individual behavior but also structural and cultural influences that shape women’s capacity as health advocates in their families. The Participatory Action Research (PAR) framework enabled researchers and participants to collaboratively examine and reflect on women who demonstrated the ability to intervene directly in their household’s smoking behavior by implementing smoke-free rules, placing visual reminders (e.g., no-smoking signs), engaging in emotional dialogue with their husbands, and leveraging religious and community figures to reinforce anti-smoking messages. The following research questions were formulated:

What roles do women play in influencing the smoking cessation behavior of their family members in Acehnese households?

What are the predisposing factors (e.g., knowledge, attitudes, and intentions) that affect women’s involvement in supporting smoking cessation within the family?

How do enabling factors (e.g., access to health services, economic conditions, and health education) facilitate or hinder women’s efforts in promoting smoke-free home environments?

What reinforcing factors (e.g., religious values, family support, and local regulations) contribute to the effectiveness of women’s advocacy in controlling smoking behavior at home?

How do women perceive their roles and responsibilities as health advocates within their households and communities concerning smoking behavior?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study employed an independent, exploratory qualitative design, guided by the Participatory Action Research (PAR) framework and the PRECEDE-PROCEED model [

32]. Rather than implementing structured interventions, this study examined the cultural, social, and behavioral factors that influence women’s roles in household smoking cessation. Emphasis was placed on the co-construction of knowledge, where women and their families collaboratively developed practical strategies such as creating smoke-free zones, setting no-smoking times (e.g., during meals or around children), and displaying handwritten reminders. These strategies emerged through mutual dialogue and negotiation, reflecting women’s growing agency in health-related household decisions. Data were collected through two rounds of semi-structured interviews conducted at participants’ homes between June 2023 and March 2024. The first session gathered initial narratives, while the second session validated transcripts and confirmed emerging themes, thereby enhancing the trustworthiness of the findings. This participatory, iterative method underscores the importance of lived experiences in shaping culturally sensitive health advocacy and promoting behavioral change.

In line with the Participatory Action Research (PAR) framework, several participatory tools were employed to ensure that participants were not only sources of data but also active co-constructors of knowledge. These included the following:

Iterative reflective interviews, conducted in two rounds, allowing women to revisit, refine, and validate their narratives.

Photovoice exercises, where participants captured household contexts (e.g., children’s exposure to smoking, family routines) using mobile phone photos. These images then served as discussion triggers in interviews, deepening reflections on women’s roles and household dynamics.

Social mapping, which engaged participants in identifying local actors (e.g., PKK groups, midwives, religious leaders) and community spaces that could support smoke-free home initiatives.

These participatory tools extended the study beyond descriptive accounts and encouraged women to articulate strategies, negotiate household norms, and envision actionable steps for creating smoke-free environments. Thus, the PAR approach in this study was not limited to documenting experiences but also aimed at stimulating critical reflection and collective awareness toward behavioral change.

2.2. Study Setting and Participants

This study was conducted in three districts in Aceh Province, Indonesia: Aceh Singkil, Gayo Lues, and Pidie Jaya. These areas were intentionally chosen to reflect a diversity of local cultural and socioeconomic conditions. A total of 75 female participants were recruited through purposive and snowball sampling techniques. The inclusion criteria included women aged 18–50 years who were married and residing in the same household as a family member who had quit smoking for at least one year, had lived in the selected location for a minimum of one year, were physically and mentally healthy, and were willing to participate and provide informed consent. This study is categorized as participatory because it engaged women in reflecting on their roles and eliciting their lived experiences and insights, which are expected to serve as the foundation for designing future promotive public health programs.

2.3. Data Collection and Saturation

This study collected data through in-depth, semi-structured interviews conducted between June 2023 and March 2024 in participants’ homes, using either Bahasa Indonesia or the Acehnese dialect, depending on each participant’s language preference. To enhance data credibility, each participant was interviewed twice in the first session, aiming to gather initial narratives, while the second was conducted to verify transcripts and confirm emerging themes. The smoking status of husbands was determined through subjective self-reports provided by their wives, based on daily observations within the household. No biometric assessments or clinical verification methods were employed, as this study’s qualitative orientation emphasized capturing the women’s lived experiences and perceived relational dynamics rather than objectively measured behaviors. In this context, smoking cessation was operationally defined as the husband’s conscious effort to refrain from smoking within the home, particularly in the presence of children or other family members. This definition reflects a behavioral and relational shift rather than clinically confirmed abstinence. In addition to interviews, the use of photovoice and social mapping provided participatory spaces for women to critically reflect on their roles and collaboratively identify feasible strategies for smoke-free households.

2.4. Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted using NVivo 15 software to facilitate systematic data coding and the identification of themes. The process included first-cycle coding—the initial open coding of interview transcripts to identify relevant statements and meanings—and second-cycle coding, which involved grouping and refining codes into broader categories and themes. Themes were organized in alignment with Lawrence Green’s PRECEDE model, focusing on predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors that influence smoking cessation behaviors in the family.

2.5. Data Trustworthiness (Validity and Reliability)

To establish the validity and reliability of the qualitative data, Lincoln and Guba’s four trustworthiness criteria were applied: Credibility: Achieved through prolonged engagement, triangulation across participant backgrounds and locations, and member checking via follow-up interviews. Transferability: Enhanced by providing thick descriptions of cultural context and participant experiences from three diverse districts. Dependability: Ensured through a transparent audit trail of data collection and analysis procedures and the consistent application of the interview protocol. Confirmability: Supported by the use of direct participant quotations and reflective journaling to minimize researcher bias.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Syiah Kuala University, No. 102/EA/FK/2023. All participants signed informed consent forms after being informed of the research objectives, procedures, and their right to withdraw at any time. Confidentiality was maintained by anonymizing all participant identifiers. This study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

4. Discussion

The discussion in this study centers on the transformative role of women as key agents in promoting tobacco control within the household setting, drawing on qualitative insights from Aceh, Indonesia. In a region deeply rooted in cultural and religious values, women were found to actively shape smoke-free environments through advocacy, emotional communication, and social persuasion. Their actions reflect a dynamic interplay between gender, health literacy, and community norms, where empowerment serves as both a catalyst and a product of health interventions at the family level. By examining how women negotiate influence within traditionally male-dominated households, this study situates their contributions within broader efforts to promote public health equity and behavioral change in low-resource, culturally embedded contexts.

Notably, the smoking status of husbands in this study was reported through the narratives of their wives, based on everyday observations within the household. No objective verification methods, such as clinical assessments or direct observation, were employed. This approach is consistent with this study’s qualitative aim to capture lived experiences and perceived realities, rather than to quantify smoking behavior. Rather than a limitation, the subjective nature of these data reflects the central focus on understanding how women interpret, respond to, and act upon smoking within their domestic environments.

Building on this, this study explicitly highlights the role of women as agents of change in household-level tobacco control. Interview findings revealed that women were not merely passive recipients of secondhand smoke exposure but actively contributed to shaping smoke-free home environments through emotional communication, social persuasion, and health advocacy. These narratives highlight the importance of empowering women in household health decision making and demonstrate how agency is exercised through relational strategies and informal negotiation, thereby underscoring their central role in promoting healthier family practices.

Women play a central role as agents of change in promoting family health, particularly in reducing exposure to tobacco smoke within the household. Through emotional appeals, interpersonal communication, and role modeling, they actively educate family members and establish rules to create a smoke-free home environment. Previous studies have shown that women often serve as key drivers of health promotion due to their moral and emotional roles as mothers and wives [

33]. Therefore, empowering women through enhanced health literacy and social support is crucial for strengthening their impact on behavioral change toward a healthier family lifestyle.

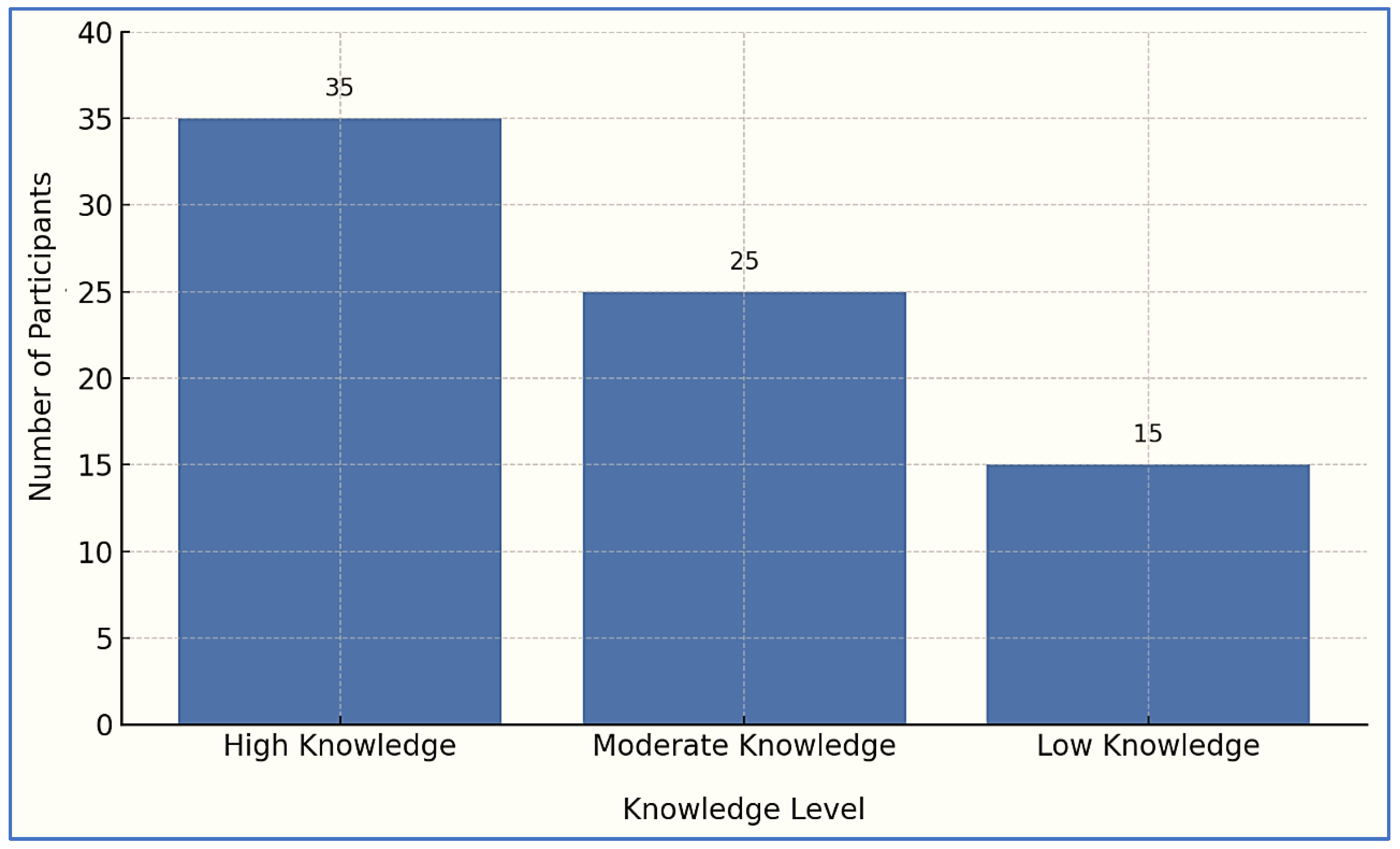

Knowledge and attitudes serve as key predisposing factors influencing women’s participation in advocating for smoke-free environments. The higher their understanding of the health risks associated with smoking, particularly secondhand smoke, the more proactive and confident they become in initiating behavioral change within the household. This correlation is supported by previous research, which highlights that increased health literacy significantly enhances women’s engagement in health-promoting behaviors [

34]. Thus, educational interventions that improve women’s awareness are essential to fostering their role as effective advocates for smoking cessation in family settings.

Enabling conditions such as access to health information, prior involvement in education campaigns, and exposure to community outreach programs significantly enhance women’s capacity and motivation to advocate for smoke-free households. These factors not only equip women with the necessary knowledge but also build their confidence and communication skills, enabling them to influence family behavior. Studies have shown that environments with supportive health infrastructure and regular public health messaging empower women to take active roles in shaping household norms and protecting family well-being [

35]. Such conditions are, therefore, essential in translating awareness into concrete advocacy actions.

Social and religious legitimacy plays a crucial role in strengthening women’s ability to take assertive action in promoting health within the family, particularly regarding smoking behavior. Support from spiritual leaders, customary laws, and prevailing community norms provides women with moral and social justification to speak out and influence change. This legitimacy not only protects them from social resistance but also amplifies their authority in traditionally patriarchal contexts. Prior research emphasizes that religious and cultural endorsement can significantly boost women’s participation in public health advocacy, turning personal concern into socially recognized action [

36].

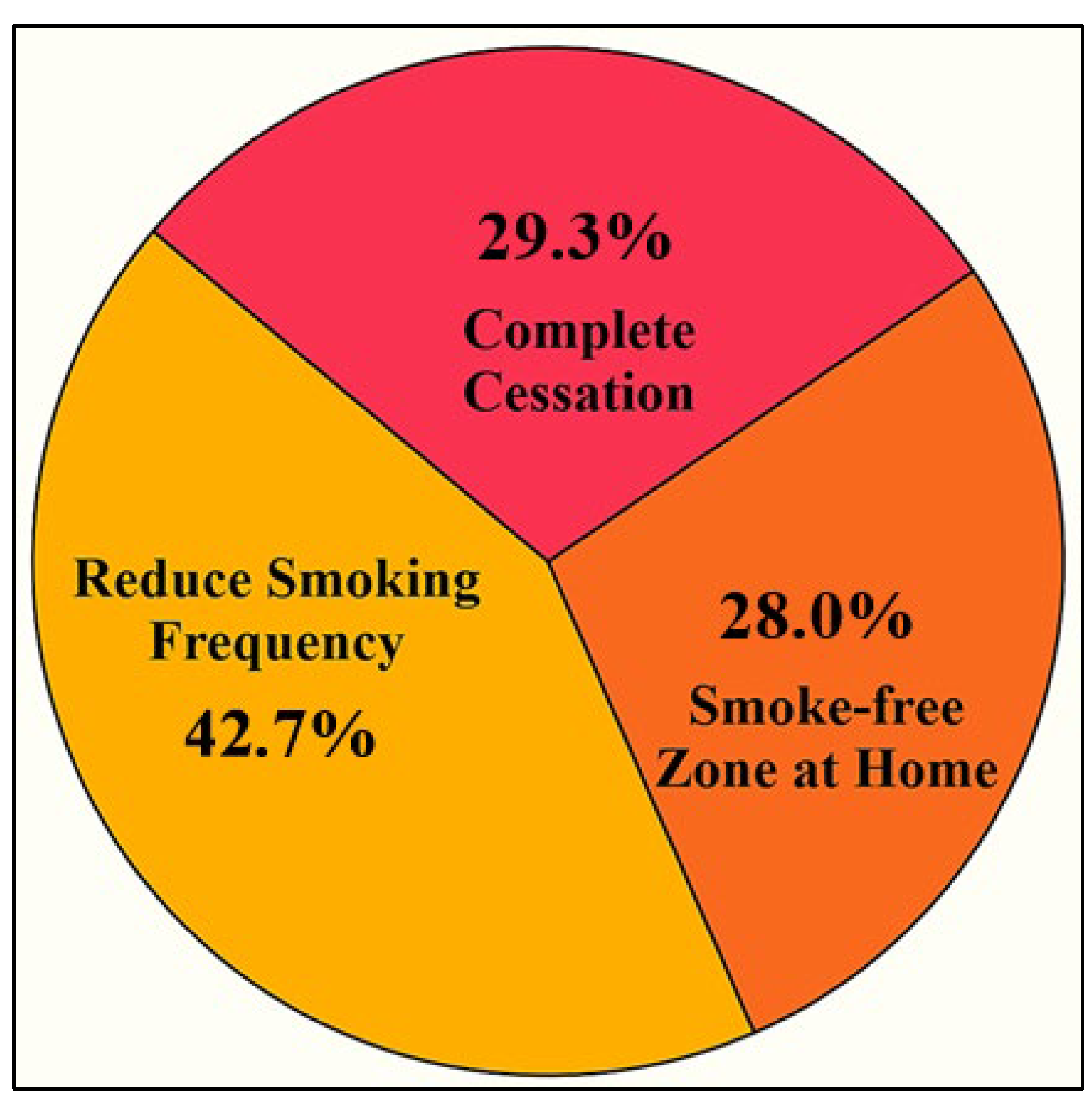

Women in this study reported tangible changes in household smoking behaviors as a result of their advocacy efforts. These changes included a reduction in smoking frequency, the establishment of designated smoke-free zones, and, in some cases, complete cessation, particularly among their spouses. Such transformations were attributed to a combination of persistent communication, emotional appeals, health education, and social reinforcement. These findings underscore the influential role women play in shaping healthier domestic environments, aligning with previous studies that highlight the effectiveness of female-led health interventions within families [

37].

Women employed adaptive strategies to overcome social and patriarchal barriers when promoting smoke-free behaviors within the household. Faced with resistance from their husbands or constrained by traditional gender norms, they resorted to indirect yet effective methods, such as initiating informal discussions, expressing emotional concerns related to family health, and involving influential third parties, like religious leaders or children. These approaches reflect their ability to navigate complex power dynamics while maintaining cultural harmony. Previous studies have similarly noted that women often rely on relational communication and community figures to assert influence in health matters within patriarchal settings [

38].

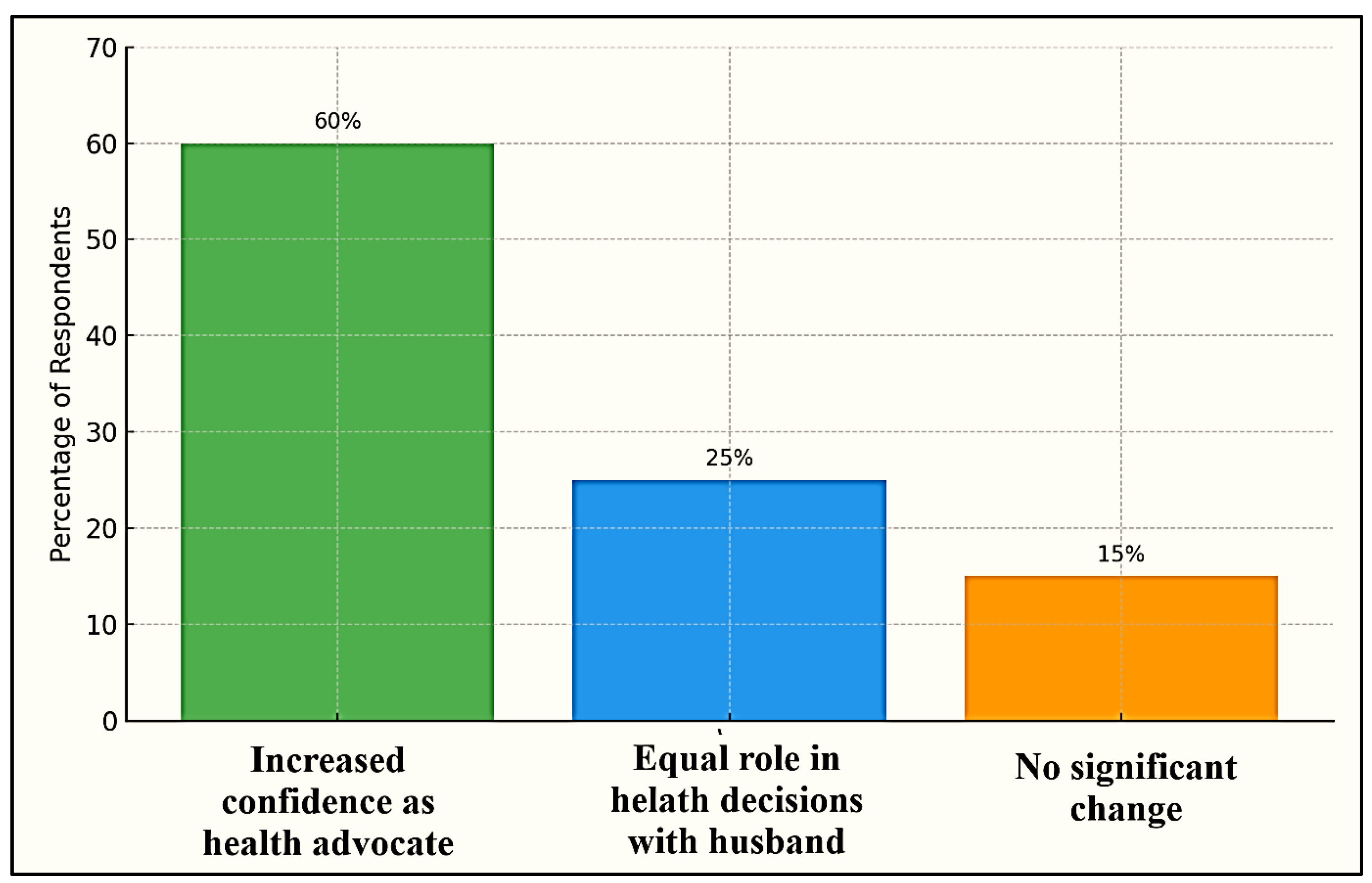

Women’s involvement in health advocacy represents a significant transformation in gender roles, shifting from traditional domestic responsibilities to emerging leadership roles in the family and community health domain. This transition is characterized by increased confidence, assertiveness, and influence in shaping health-related decisions, particularly regarding smoking behaviors. Rather than being confined to caregiving tasks, women are now seen and see themselves as proactive health agents. This role expansion aligns with broader patterns of gender empowerment observed in the health promotion literature, where women’s participation in public health efforts is linked to both individual agency and structural support [

39]. Such a shift not only enhances family well-being but also contributes to long-term gender equity in decision-making spheres.

The role of emotion and interpersonal communication emerges as a crucial strategy in women’s advocacy for healthier family environments. By employing messages grounded in affection, empathy, and concern, particularly for children’s well-being, women can persuade family members to reduce or quit smoking effectively. Emotional appeals resonate more deeply within familial relationships, fostering a sense of guilt or responsibility in smokers. For instance, reminders framed around the health risks to children or expressions of maternal concern tend to generate more receptive responses. These communication styles, rooted in empathy and relational bonds, have been identified in previous studies as practical tools for initiating behavior change within domestic settings [

40]. Thus, emotional and empathetic communication strengthens women’s influence and reinforces their role as trusted advocates in the household.

Community-based and gender-sensitive health education programs have shown a significant impact in empowering women as key agents of change in promoting healthy behaviors within families. When women are actively involved as participants, facilitators, or peer educators, these programs become more relatable and culturally aligned, increasing their acceptance and sustainability. Research has demonstrated that such gender-inclusive approaches enhance the credibility of health messages and improve adherence to behavior change, especially in patriarchal communities where women’s voices may otherwise be marginalized [

41]. By integrating women’s lived experiences and leadership roles into health interventions, these programs not only address immediate issues, such as tobacco exposure, but also contribute to long-term shifts in gender norms and family health decision-making dynamics.

This study demonstrates the transformational dimension of Participatory Action Research (PAR) in several ways. First, the use of photovoice and reflective discussions allowed women to critically examine their household environments and articulate smoking-related risks that were previously taken for granted. Second, through iterative dialogues, women negotiated concrete behavioral changes within their families, such as establishing smoke-free zones inside the home, limiting smoking to outdoor areas, and introducing household reminders (e.g., notes on the wall). Third, the process of social mapping expanded women’s awareness of potential community-level support systems, including PKK groups, midwives, and religious leaders, thereby linking individual household practices to wider social structures. These participatory processes go beyond documenting lived experiences; they stimulated critical reflection, fostered women’s agency in health decision making, and catalyzed collective awareness of the importance of creating smoke-free environments. Thus, this study embodies the transformational goal of PAR by translating participants’ reflections into tangible shifts in household norms and social consciousness.

This study contributes to the development of gender and health literacy in local communities by emphasizing the importance of culturally grounded, gender-responsive approaches in public health interventions. By recognizing women not merely as passive recipients but as active health advocates shaped by local norms and values, the research highlights how gender-sensitive frameworks rooted in community identity can enhance the relevance and effectiveness of health programs. The integration of local wisdom, religious teachings, and familial structures into advocacy strategies fosters trust and engagement, ultimately leading to more sustainable behavioral changes [

42]. These findings align with global recommendations that stress the intersection of gender equity and health education in achieving community health resilience [

43].

5. Conclusions

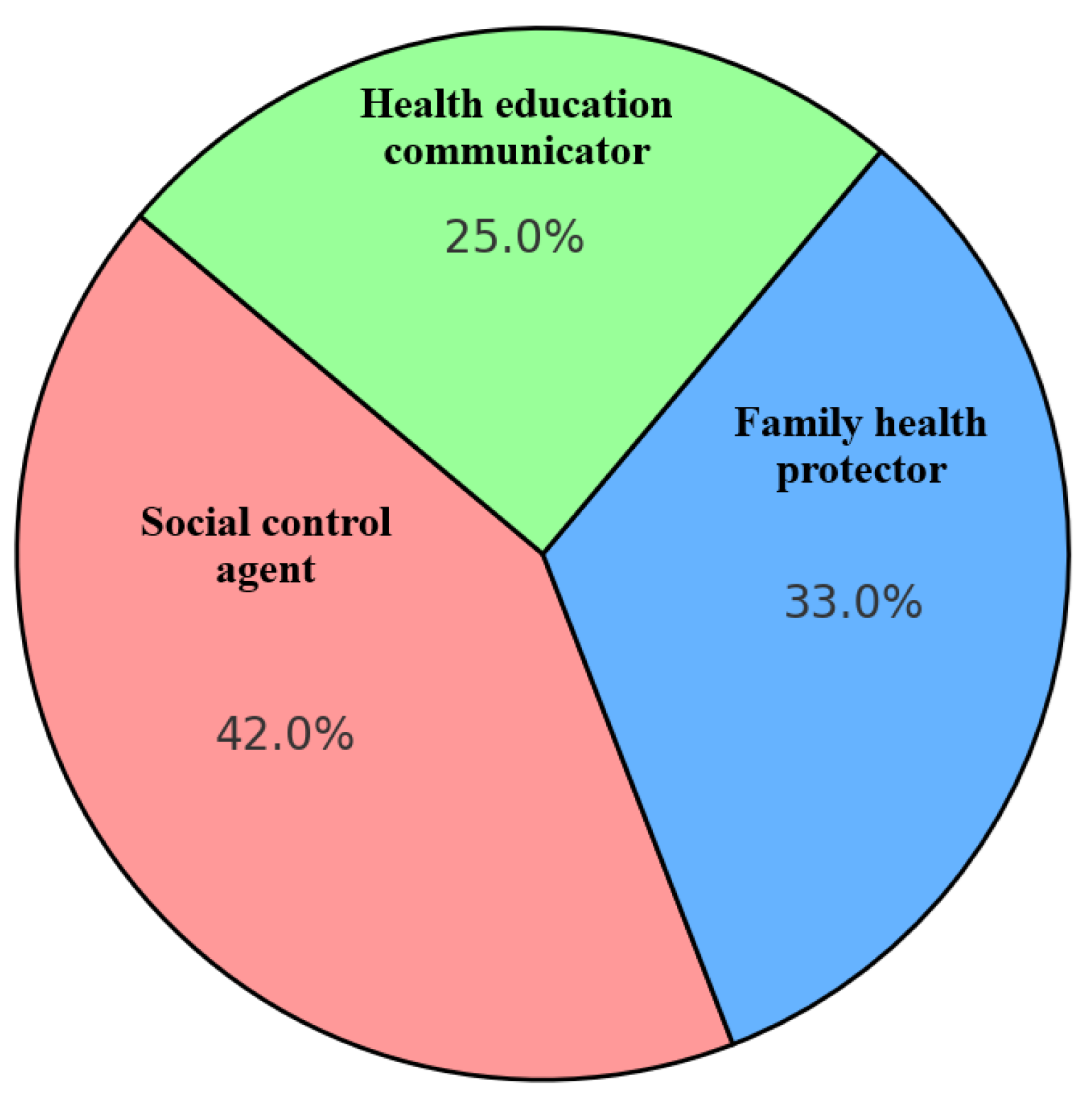

Based on the findings, this study concludes that women play a central role as agents of change in controlling smoking behavior at the household level in Aceh, Indonesia. They actively take on roles as social regulators, health communicators, and family protectors through empathetic interpersonal approaches, knowledge of smoking hazards, and the social and religious legitimacy they receive. Predisposing factors such as awareness levels; enabling conditions such as access to health information and prior educational experiences; and support from social institutions, including religious leaders and community norms, further strengthen their capacity to act.

Tangible behavioral changes, such as reduced smoking frequency, the establishment of smoke-free zones, and even complete cessation among spouses, demonstrate the effectiveness of women’s advocacy efforts. Despite facing social barriers and patriarchal norms, women developed adaptive strategies, including informal discussions, emotional appeals, and the involvement of third parties (e.g., religious leaders or children). This also reflects a transformation in gender roles from traditional domestic roles to leadership in family health matters. This study highlights that empowering women through health literacy and community support significantly contributes to creating smoke-free home environments and fostering healthier family behavior.