Applying Design Thinking for Co-Designed Health Solutions: A Case Study on Chronic Kidney Disease in Regional Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

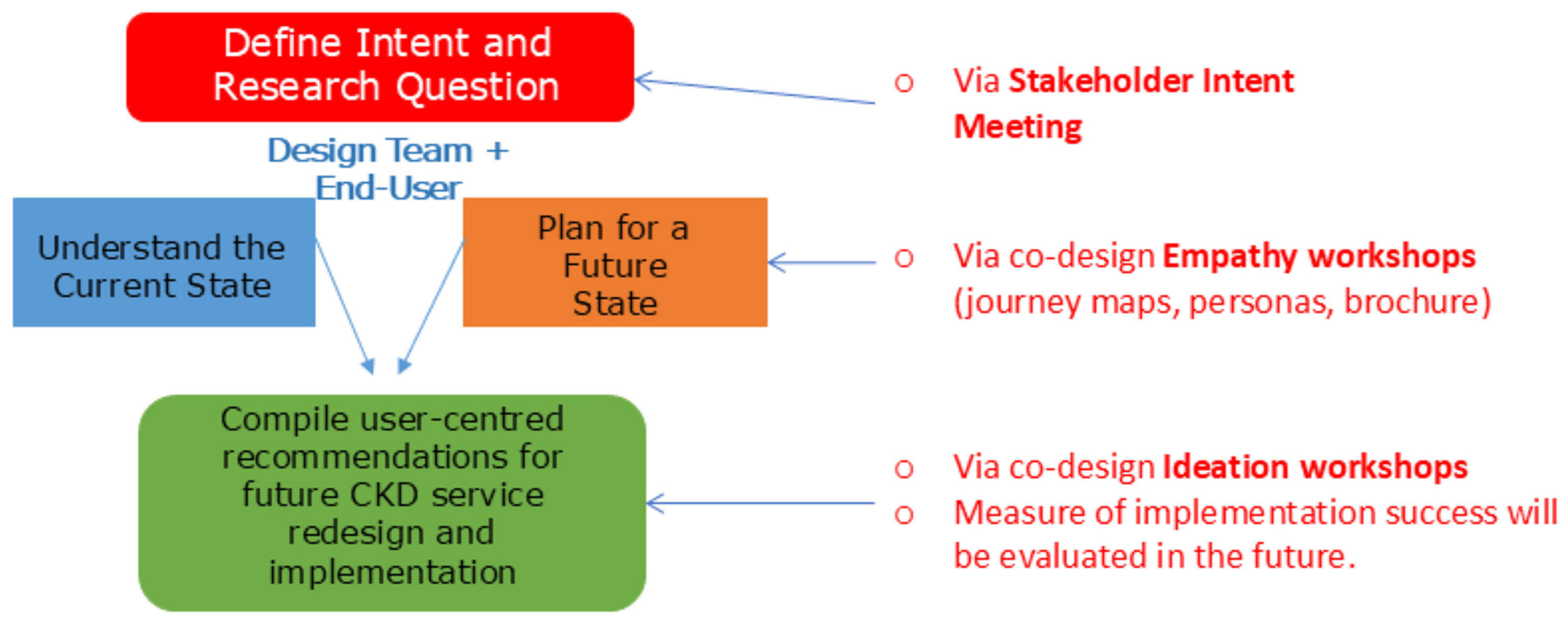

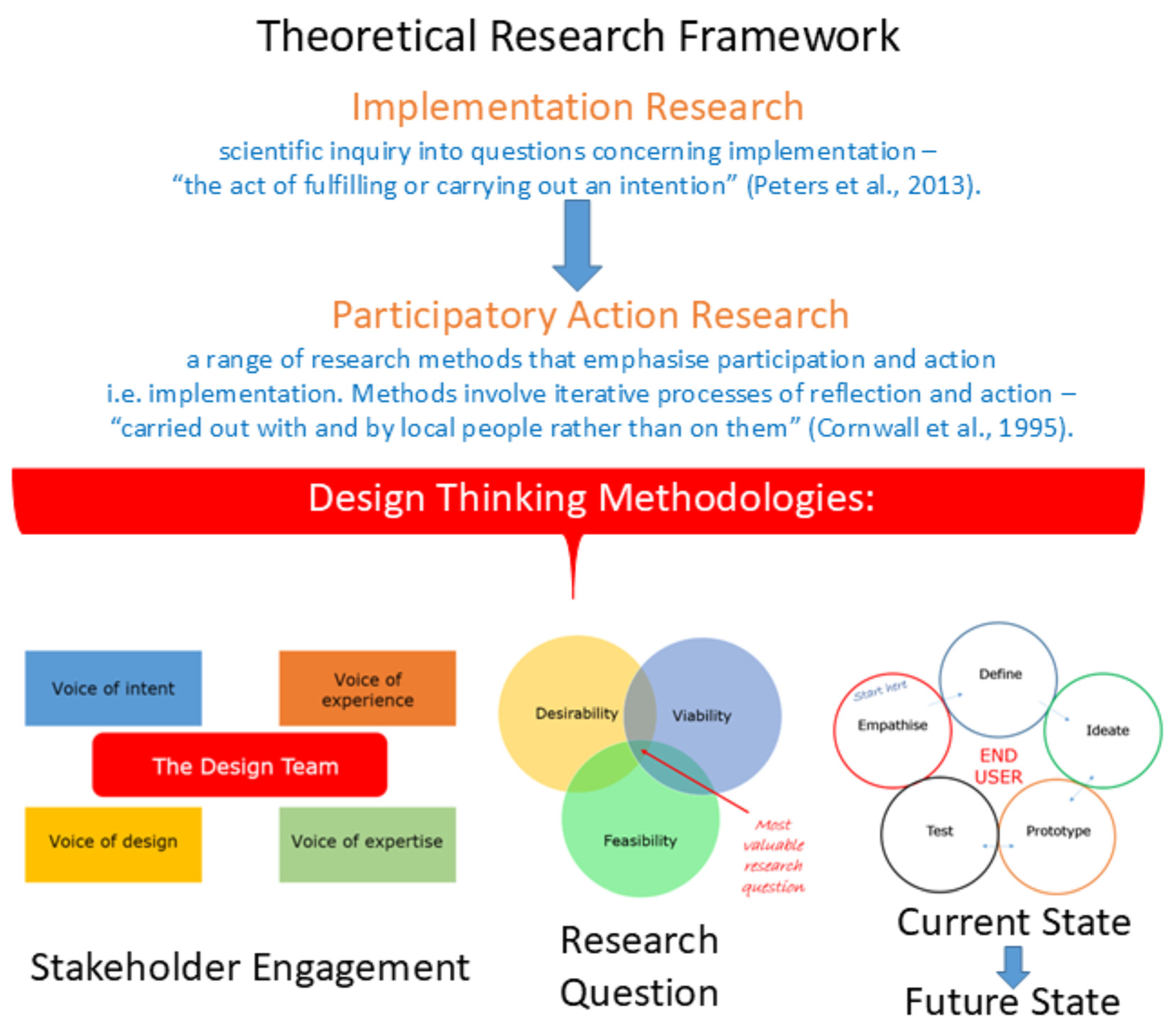

2. Materials and Methods

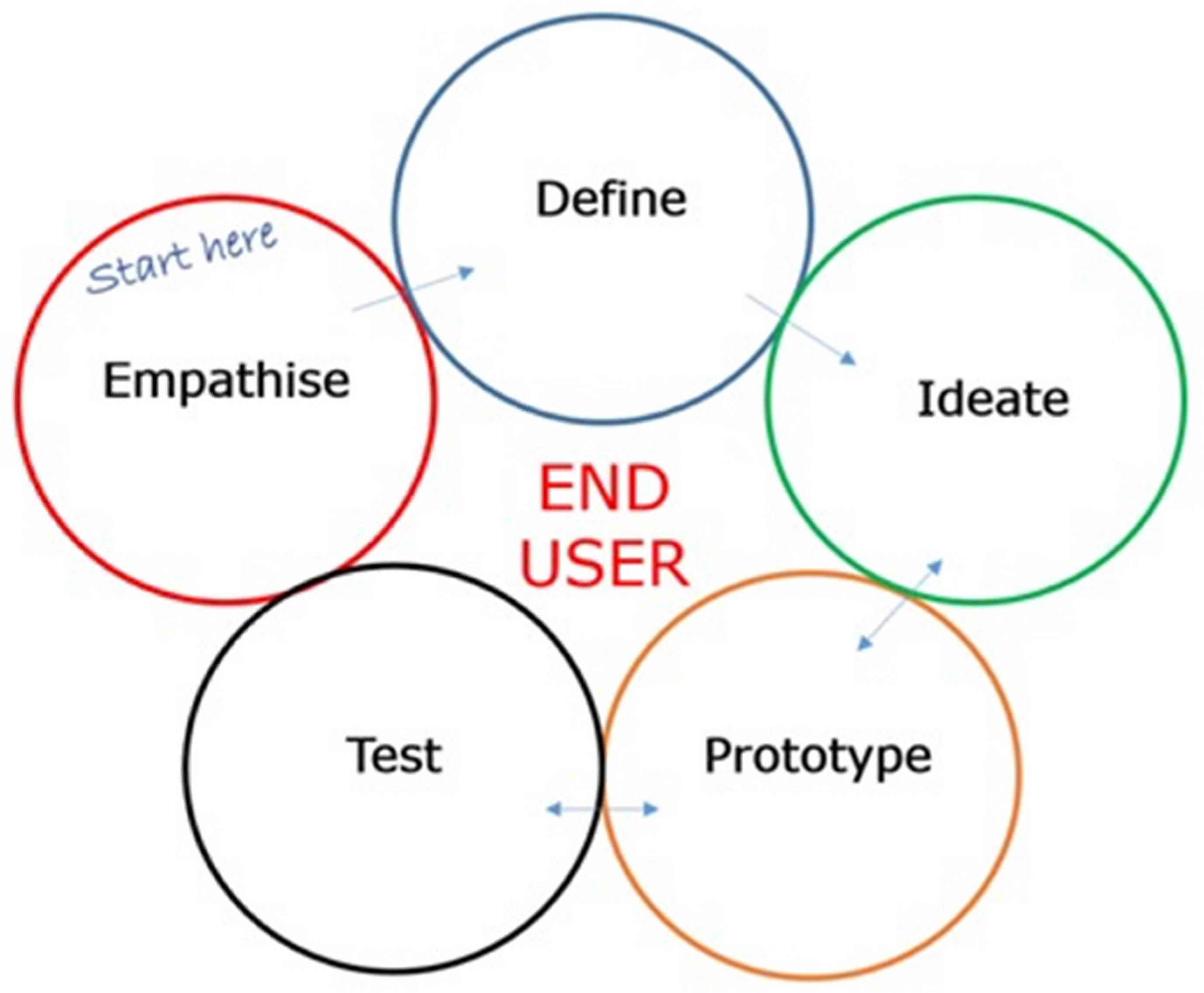

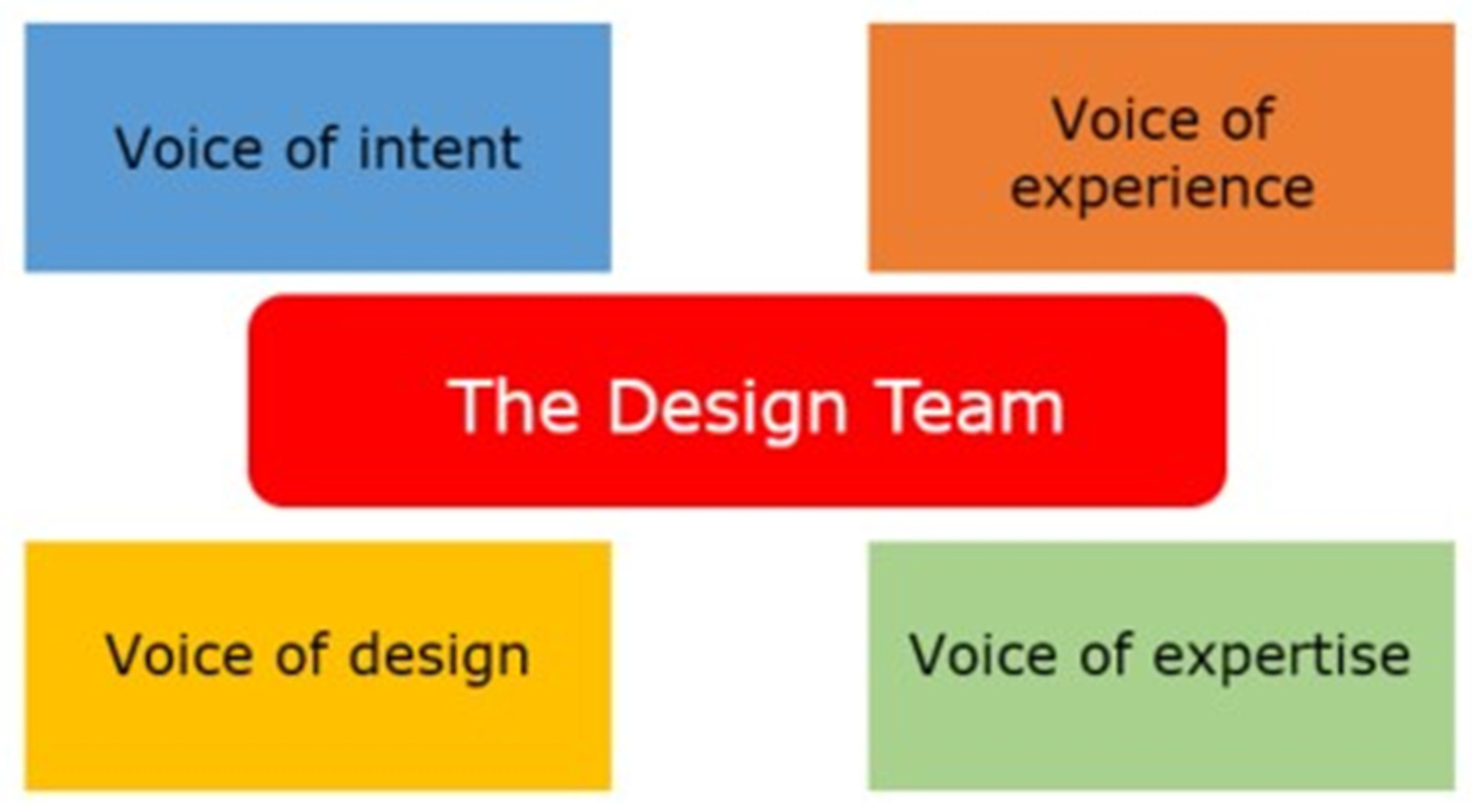

2.1. Overview of Design Thinking

2.2. Community Engagement Is Essential in the Design of Person-Centred Health Care for People Living with CKD

3. Results

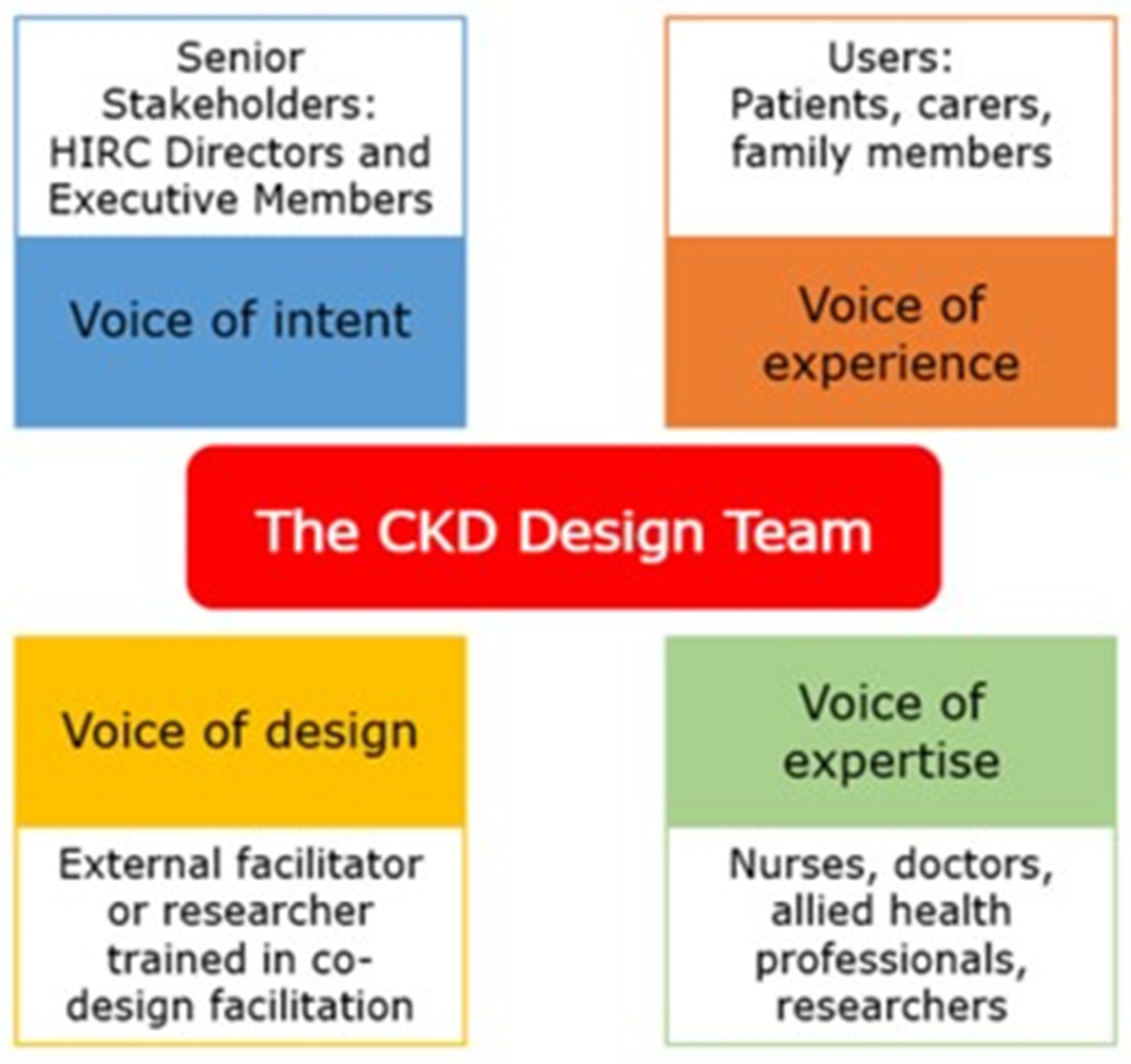

- Step 1: Recruitment of Stakeholders to Represent the Four Design Voices

- Step 2: Defining the Project’s Intent, Problem Statement, and Setting Expectations

- Step 3: Empathising with the End Users to Collect Valuable Insights (Data) and Define the Problem, and Ideate Potential Solutions

3.1. Empathy Workshops

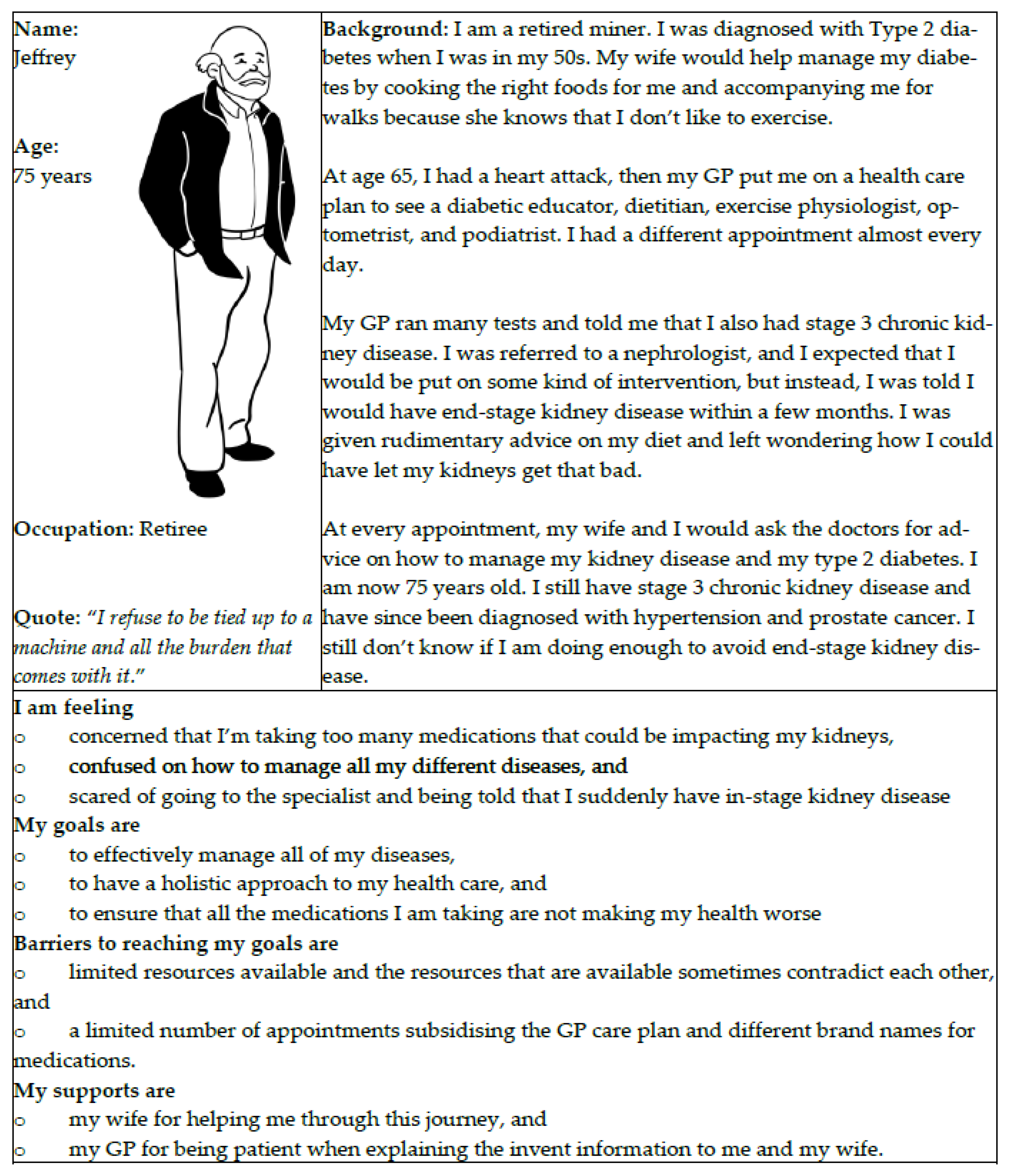

3.2. Personas

3.3. Ideation Workshops

3.4. Interviews

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Health Conditions Prevalence, 2020–2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/health-conditions-prevalence/ (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Hassan, H.I.C.; Lambert, K.; Moules, S.; Mcalister, B.J.; Murali, K. Mapping CKD Prevalence Burden in a Reportedly High Australian Health District Region: TH-PO1009. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 34, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, W.B.; Cody, W.R.; Boff, K.R. The human factors of system design: Understanding and enhancing the role of human factors engineering. Int. J. Hum. Factors Manuf. 1991, 1, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. Design thinking. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Carmel-Gilfilen, C.; Portillo, M. Designing With Empathy: Humanizing Narratives for Inspired Healthcare Experiences. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2015, 9, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasanidou, D.; Gasparini, A.A.; Lee, E. Design Thinking Methods and Tools for Innovation. In Design, User Experience, and Usability: Design Discourse; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Marcus, A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 9186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. Design Thinking Defined. Available online: https://designthinking.ideo.com/ (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Roberts, J.P.; Fisher, T.R.; Trowbridge, M.J.; Bent, C. A design thinking framework for healthcare management and innovation. Healthcare 2016, 4, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Searl, M.M.; Borgi, L.; Chemali, Z. It is time to talk about people: A human-centered healthcare system. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2010, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devecchi, A.; Guerrini, L. Empathy and Design. A new perspective. Des. J. 2017, 20, S4357–S4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ThinkPlace Global. Available online: https://www.thinkplace.com.au/ (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Floyd, I.R.; Cameron Jones, M.; Twidale, M.B. Resolving Incommensurable Debates: A Preliminary Identification of Persona Kinds, Attributes, and Characteristics. Artifact 2008, 2, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, R.J.; Kulanthaivel, A.; Purkayastha, S.; Goggins, K.M.; Kripalani, S. Know thy eHealth user: Development of biopsychosocial personas from a study of older adults with heart failure. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2017, 108, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruitt, J.; Adlin, T. The Persona Lifecycle: Keeping People in Mind Throughout Product Design; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stefoska-Needham, A.; Fildes, K.; Atkinson, J.; Nealon, J.; Charton, K.; Gutker, M.; Lambert, K.; Anna, L.; Smyth, M.; Walton, K. SUN-247 Experiencing chronic kidney disease: Perspectives of individuals living with chronic kidney disease, their family members, carers and health professionals. Kidney Int. Rep. 2019, 4, S262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickdorn, M.; Hormess, M.E.; Lawrence, A.; Schneider, J. This Is Service Design Doing: Applying Service Design Thinking in the Real World; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sevastopol, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, R. Wicked problems in design thinking. Des. Issues 1992, 8, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, T.; Brandt, E.; Gregory, J. Design participation(-s)—A creative commons for ongoing change. CoDesign 2008, 4, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, M.; Huang, T.T.; Breland, J.Y. Design thinking in health care. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2018, 15, E117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donetto, S.; Tsianakas, V.; Robert, G. Using Experience-Based Co-Design (EBCD) to Improve the Quality of Healthcare: Mapping Where We Are Now and Establishing Future Directions; King’s College London: London, UK, 2014; pp. 5–7. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Using-Experience-based-Co-design-(EBCD)-to-improve-Donetto-Tsianakas/259c2ebc8e3e39c42c4a1ac50df8ccd2f1e04994 (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Lo, C.; Zimbudzi, E.; Teede, H.; Cass, A.; Fulcher, G.; Gallagher, M.; Kerr, P.G.; Jan, S.; Johnson, G.; Mathew, T. Models of care for co-morbid diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Nephrology 2018, 23, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, G.; Cornwell, J.; Locock, L.; Purushotham, A.; Sturmey, G.; Gager, M. Patients and staff as codesigners of healthcare services. BMJ 2015, 350, g7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; de Jong, P.E.; Coresh, J.; El Nahas, M.; Astor, B.C.; Matsushita, K.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Kasiske, B.L.; Eckardt, K.U. The definition, classification, and prognosis of chronic kidney disease: A KDIGO Controversies Conference report. Kidney Int. 2011, 80, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, M.; Wiebe, N.; Guthrie, B.; James, M.T.; Quan, H.; Fortin, M.; Klarenbach, S.W.; Sargious, P.; Straus, S.; Lewanczuk, R.; et al. Comorbidity as a driver of adverse outcomes in people with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2015, 88, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S.; Vecchio, M.; Craig, J.C.; Tonelli, M.; Johnson, D.W.; Nicolucci, A.; Pellegrini, F.; Saglimbene, V.; Logroscino, G.; Fishbane, S. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int. 2013, 84, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, M.K.; Rankin, A.J.; Jani, B.D.; Mair, F.S.; Mark, P.B. Associations between multimorbidity and adverse clinical outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e038401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Patient Centred Care: Improving Quality and Safety Through Partnerships with Patients and Consumers. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/patient-centred-care-improving-quality-and-safety-through-partnerships-patients-and-consumers (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Hill, C.J.; Cardwell, C.R.; Patterson, C.C.; Maxwell, A.P.; Magee, G.M.; Young, R.J.; Matthews, B.; O’Donoghue, D.J.; Fogarty, D.G. Chronic kidney disease and diabetes in the national health service: A cross-sectional survey of the U.K. national diabetes audit. Diabet. Med. 2014, 31, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, O.; Mekala, D.P.; Patel, D.V.; Fornoni, A.; Metz, D.; Roth, D. Barriers to successful care for chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2005, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Mahoney, E.R.; Stockard, J.; Tusler, M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv. Res. 2005, 40, 1918–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.; Teede, H.; Ilic, D.; Russell, G.; Murphy, K.; Usherwood, T.; Ranasinha, S.; Zoungas, S. Identifying health service barriers in the management of co-morbid diabetes and chronic kidney disease in primary care: A mixed-methods exploration. Fam. Pract. 2016, 33, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbudzi, E.; Lo, C.; Ranasinha, S.; Gallagher, M.; Fulcher, G.; Kerr, P.G.; Russell, G.; Teede, H.; Usherwood, T.; Walker, R.; et al. Predictors of Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Co-Morbid Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoll, R.; Robertson, L.; Gemmell, E.; Sharma, P.; Black, C.; Marks, A. Models of care for chronic kidney disease: A systematic review. Nephrology 2018, 23, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanachayanont, T.; Chanpitakkul, M.; Hengtrakulvenit, J.; Watcharakanon, P.; Wisansak, W.; Tancharoensukjit, T.; Kaewsringam, P.; Leesmidt, V.; Pongpirul, K.; Lekagul, S.; et al. Effectiveness of integrated care on delaying chronic kidney disease progression in rural communities of Thailand (ESCORT-2) trials. Nephrology 2021, 26, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.J.; Hou, Y.H.; Chang, R.E. The Impact of a Social Networking Service-Enhanced Smart Care Model on Stage 5 Chronic Kidney Disease: Quasi-Experimental Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e15565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fildes, K.; Stefoska-Needham, A.; Atkinson, J.; Lambert, K.; Lee, A.; Pugh, D.; Smyth, M.; Turner, R.; Wallace, S.; Nealon, J. Optimising health care for people living with chronic kidney disease: Health-professional perspectives. J. Ren. Care 2022, 48, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, E.P.; Middleton, J.; Lambert, K. Barriers and enablers to detection and management of chronic kidney disease in primary healthcare: A systematic review. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSW Government Agency for Clinical Innovation. Patient Experience and Consumer Engagement: A Framework for Action. Available online: https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/502240/Guide-Build-Codesign-Capability.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Fildes, K.; Nealon, J.; Charlton, K.; Lambert, K.; Lee, A.; Pugh, D.; Smyth, M.; Stefoska-Needham, A. Collaborative codesign: Unveiling concerns and crafting solutions for healthcare with health professionals, carers and consumers with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Dial. 2025, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rijnsoever, F.J. (I Can’t Get No) Saturation: A simulation and guidelines for sample sizes in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, H.; Bailey-Ross, C.; Kendal, J.; Mursic, Z.; Lloyd, A.; Ross, B.; Kendal, R.L. Multidisciplinary exhibit design in a Science Centre: A participatory action research approach. Educ. Action Res. 2018, 26, 567–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleberry, A.; Nolen, A. Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: Is it as easy as it sounds? Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. 2022, 9, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, D.H.; Adam, T.; Alonge, O.; Agyepong, I.A.; Tran, N. Implementation research: What it is and how to do it. BMJ 2013, 347, f6753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornwall, A.; Jewkes, R. What is participatory research? Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donetto, S.; Pierri, P.; Tsianakas, V.; Robert, G. Experience-based co-design and healthcare improvement: Realizing participatory design in the public sector. Des. J. 2015, 18, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stefoska-Needham, A.; Nealon, J.; Charlton, K.; Fildes, K.; Lambert, K. Applying Design Thinking for Co-Designed Health Solutions: A Case Study on Chronic Kidney Disease in Regional Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101475

Stefoska-Needham A, Nealon J, Charlton K, Fildes K, Lambert K. Applying Design Thinking for Co-Designed Health Solutions: A Case Study on Chronic Kidney Disease in Regional Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101475

Chicago/Turabian StyleStefoska-Needham, Anita, Jessica Nealon, Karen Charlton, Karen Fildes, and Kelly Lambert. 2025. "Applying Design Thinking for Co-Designed Health Solutions: A Case Study on Chronic Kidney Disease in Regional Australia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101475

APA StyleStefoska-Needham, A., Nealon, J., Charlton, K., Fildes, K., & Lambert, K. (2025). Applying Design Thinking for Co-Designed Health Solutions: A Case Study on Chronic Kidney Disease in Regional Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101475