A Study of Relationships Between Mental Well-Being, Sleep Quality, Eating Behavior, and BMI: A Cross-Sectional Study Among University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. The DASS-42—The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale

2.3. Three Factors Eating Questionnaire R18V2

2.4. PSQI—Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

2.5. BMI—Body Mass Index

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study’s Participants

3.2. The Results of DASS-42

3.3. The Results of the Three-Factors Eating Questionnaire

3.4. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

3.5. Correlations Between BMI, PSQI, DASS-42, and R18V2

4. Discussion

Limitations of Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LBTU | Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| DASS | Depression, anxiety, and stress scale |

| R18V2 | Three-factor eating questionnaire |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh sleep quality index |

References

- WHO—World Health Organization. Mental Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Shah, K.; Kamrai, D.; Mekala, H.; Mann, B.; Desai, K.; Patel, R.S. Focus on Mental Health During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic: Applying Learnings from the Past Outbreaks. Cureus 2020, 12, e7405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touyz, S.; Lacey, H.; Hay, P. Eating disorders in the time of COVID-19. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limone, P.; Toto, G.A.; Messina, G. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war on stress and anxiety in students: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1081013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högberg, B. Educational stressors and secular trends in school stress and mental health problems in adolescents. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 270, 113616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuppun, J.; Muja, A.; Geurts, R. Well-Being and Mental Health Among Students in European Higher Education. EUROSTUDENT 8 Topical Module Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.eurostudent.eu/download_files/documents/TM_wellbeing_mentalhealth.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Solomou, S.; Logue, J.; Reilly, S.; Perez-Algorta, G. A systematic review of the association of diet quality with the mental health of university students: Implications in health education practice. Health Educ. Res. 2023, 38, 28–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiq, I.; Jalal, K.; Fatima, R.; Javed, A.; Waheed, W.; Batool, S.; Khan, M.A.; Fatima, M.; Ghaffar, T. Mental Health and Nutrition: A Study on the role of Anxiety and Depression in Eating Habits in College Students. J. Health Rehabil. Res. 2024, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Corezzi, M.; Bert, F.; Lo Moro, G.; Buda, A.; Gualano, M.R.; Siliquini, R. Mediterranean diet and mental health in university students: An Italian cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, ckaa166.201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, M.; Mantzorou, M.; Serdari, A.; Bonotis, K.; Vasios, G.; Pavlidou, E.; Trifonos, C.; Vadikolias, K.; Petridis, D.; Giaginis, C. Evaluating Mediterranean diet adherence in university student populations: Does this dietary pattern affect students’ academic performance and mental health? Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2020, 35, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwalska, J.; Kolasińska, K.; Łojko, D.; Bogdański, P. Eating Behaviors, Depressive Symptoms and Lifestyle in University Students in Poland. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulis, M.; Lai, A.G.; Diaz-Ordaz, K.; Gomes, M.; Pasea, L.; Banerjee, A.; Denaxas, S.; Tsilidis, K.; Lagiou, P.; Misirli, G.; et al. Identifying adults at high-risk for change in weight and BMI in England: A longitudinal, large-scale, population-based cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Mozaffari, H.; Askari, M.; Azadbakht, L. Association between overweight/obesity with depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and body dissatisfaction in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, Q.; Zhai, L.; Bai, Y.; Wei, W.; Jia, L. The Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms among Overweight/Obese and Non-Overweight/Non-Obese Children/Adolescents in China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, J.E.; Lytle, L.A.; Laska, M.N. Stress, Health Risk Behaviors, and Weight Status Among Community College Students. Health Educ. Behav. 2016, 43, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellere, I.; Beitane, I. Association of Dietary Habits with Eating Disorders among Latvian Youth Aged 18–24. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J. The Relationship between Dietary Restraint and Binge Eating: Examining Eating-related Self-efficacy as a Moderator. Appetite 2018, 127, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poínhos, R.; Oliveira, B.M.P.M.; Correia, F. Eating behavior in Portuguese higher education students: The effect of social desirability. Nutrition 2015, 31, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohyama, J. Which Is More Important for Health: Sleep Quantity or Sleep Quality? Children 2021, 8, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemann, D.; Espie, C.A.; Altena, E.; Arnardottir, E.S.; Baglioni, C.; Bassetti, C.L.A.; Bastien, C.; Berzina, N.; Bjorvatn, B.; Dikeos, D.; et al. The European Insomnia Guideline: An update on the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia 2023. J. Sleep Res. 2023, 32, e14035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, S.D.; Henry, A.L. Sleep is a modifiable determinant of health: Implications and opportunities for health psychology. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement-Carbonell, V.; Portilla-Tamarit, I.; Rubio-Aparicio, M.; Madrid-Valero, J.J. Sleep Quality, Mental and Physical Health: A Differential Relationship. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.H.; Chung, J.H. The association between sleep quality and quality of life: A population-based study. Sleep Med. 2021, 84, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.T.; Chuang, H.-L.; Kuo, C.-P.; Yeh, T.-P.; Liao, W.-C. Electronic Device Use before Bedtime and Sleep Quality among University Students. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khani, A.M.; Sarhandi, M.I.; Zaghloul, M.S.; Ewid, M.; Saquib, N. A cross-sectional survey on sleep quality, mental health, and academic performance among medical students in Saudi Arabia. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhat, G.; Lees, E.; Macdonald-Clarke, C.; Amirabdollahian, F. Inadequacies of micronutrient intake in normal weight and overweight young adults aged 18–25 years: A cross-sectional study. Public Health 2019, 167, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, L.A.; Gallo, T.F.; Young, S.L.; Fotheringham, A.K.; Barclay, J.L.; Walker, J.L.; Moritz, K.M.; Akison, L.K. Adherence to Dietary and Physical Activity Guidelines in Australian Undergraduate Biomedical Students and Associations with Body Composition and Metabolic Health: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd ed.; Psychology Foundation: Sydney, Australia, 1995; ISBN 7334-1423-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ozolina, Z. Development of the Initial Version of the Latvian Clinical Personality Test Anxiety Scale. Master’s Thesis, Rīgas Stradiņš University, Riga, Latvia, 2015. Available online: https://science.rsu.lv/ws/portalfiles/portal/52165104/SVSLFVPSMp_2015_Zane_Ozolina_.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Cappelleri, J.C.; Bushmakin, A.G.; Gerber, R.A.; Leidy, N.K.; Sexton, C.C.; Lowe, M.R.; Karlsson, J. Psychometric analysis of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire-R21: Results from a large diverse sample of obese and non-obese participants. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmane, R. Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire—R18V2 Adaptation in Latvian. Bachelor’s Thesis, Rīgas Stradiņš University, Riga, Latvia, 2022. Available online: https://dspace.rsu.lv/jspui/handle/123456789/9243 (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO—World Health Organization Body Mass Index (BMI). 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/body-mass-index?introPage=intro_3.html (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Center of Disease Prevention and Control. Health Behavior Among Latvian Adult Population. 2022. Available online: https://www.spkc.gov.lv/lv/media/18708/download?attachment (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Rahimi, T.; Barunizadeh, M.; Aune, D.; Rezaei, F. Association between health literacy and body mass index among Iranian high school students. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, N.; Gul, F.H. The relationships among food neophobia, Mediterranean diet adherence, and eating disorder risk among university students: A cross-sectional study. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2025, 44, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, H.; Abdelrahim, D.N.; Osaili, T.; Thabet, Y.; Barakat, H.; Khetrish, M.; Hawa, A.; Daoud, A.; Mahmoud, O.A.A.; Hasan, H. The association of binge eating with internet addiction, body shape concerns, and BMI among university students in the United Arab Emirates. J. Eat. Disord. 2025, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, R.; He, P.; Ling, B.; Tan, L.; Xu, L.; Hou, Y.; Kong, L.; Yang, Y. Prevalence of depression and anxiety and correlations between depression, anxiety, family functioning, social support and coping styles among Chinese medical students. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Zhao, H.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, C.; Zhai, J.; Wang, B. Depression, anxiety, stress symptoms among overweight and obesity in medical students, with mediating effects of academic burnout and internet addiction. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, J.P.; Giacomin, H.T.; Tam, W.W.; Ribeiro, T.B.; Arab, C.; Bezerra, I.M.; Pinasco, G.C. Mental health problems among medical students in Brazil: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2017, 39, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, M.A.; Dipace, A.; Monda, A.; De Maria, A.; Polito, R.; Messina, G.; Monda, M.; di Padova, M.; Basta, A.; Ruberto, M.; et al. Relationship Between Sedentary Lifestyle, Physical Activity and Stress in University Students and Their Life Habits: A Scoping Review with PRISMA Checklist (PRISMA-ScR). Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lauzon, B.; Romon, M.; Deschamps, V.; Lafay, L.; Borys, J.M.; Karlsson, J.; Ducimetière, P.; Charles, M.A.; Fleurbaix Laventie Ville Sante Study Group. The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire-R18 is able to distinguish among different eating patterns in a general population. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 2372–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdella, H.M.; El Farssi, H.O.; Broom, D.R.; Hadden, D.A.; Dalton, C.F. Eating Behaviours and Food Cravings; Influence of Age, Sex, BMI and FTO Genotype. Nutrients 2019, 11, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Strien, T. Causes of Emotional Eating and Matched Treatment of Obesity. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2018, 18, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, Z.; Loukzadeh, Z.; Moghaddam, P.; Jalilolghadr, S. Sleep hygiene practices and their relation to sleep quality in medical students of Qazvin university of medical sciences. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 5, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, C.J.; Safati, A.; Hall, P.A. The neurocognitive consequences of sleep restriction: A meta-analytic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 80, 586–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, D. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Symptoms. Available online: https://www.sleepfoundation.org/chronic-fatigue-syndrome/symptoms (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Li, L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, S.B.; Li, L.; Lu, L.; Ng, C.H.; Ungvari, G.S.; Chiu, H.F.K.; Hou, C.L.; Jia, F.J.; et al. Sleep Duration and Sleep Patterns in Chinese University Students: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. JCSM Off. Publ. Am. Acad. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuhammadi, N.; Alfawaz, W. The relationship between three-factor eating questionnaire (TFEQ) subscales (dietary restrain, disinhibition, and hunger) and the body mass index: A cross-sectional study among female students. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Strien, T.; Herman, C.P.; Verheijden, M.W. Eating style, overeating and weight gain. A prospective 2-year follow-up study in a representative Dutch sample. Appetite 2012, 59, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gürbüz, M.; Bayram, H.M. The Bidirectional Association between Internet Use, Sleep Quality and Eating Behavior: A Cross-Sectional Study in Northwestern Thrace Region in Türkiye. J. Am. Nutr. Assoc. 2024, 44, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indicators | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 264 | 66.5 |

| Male | 130 | 32.7 | |

| Other | 3 | 0.8 | |

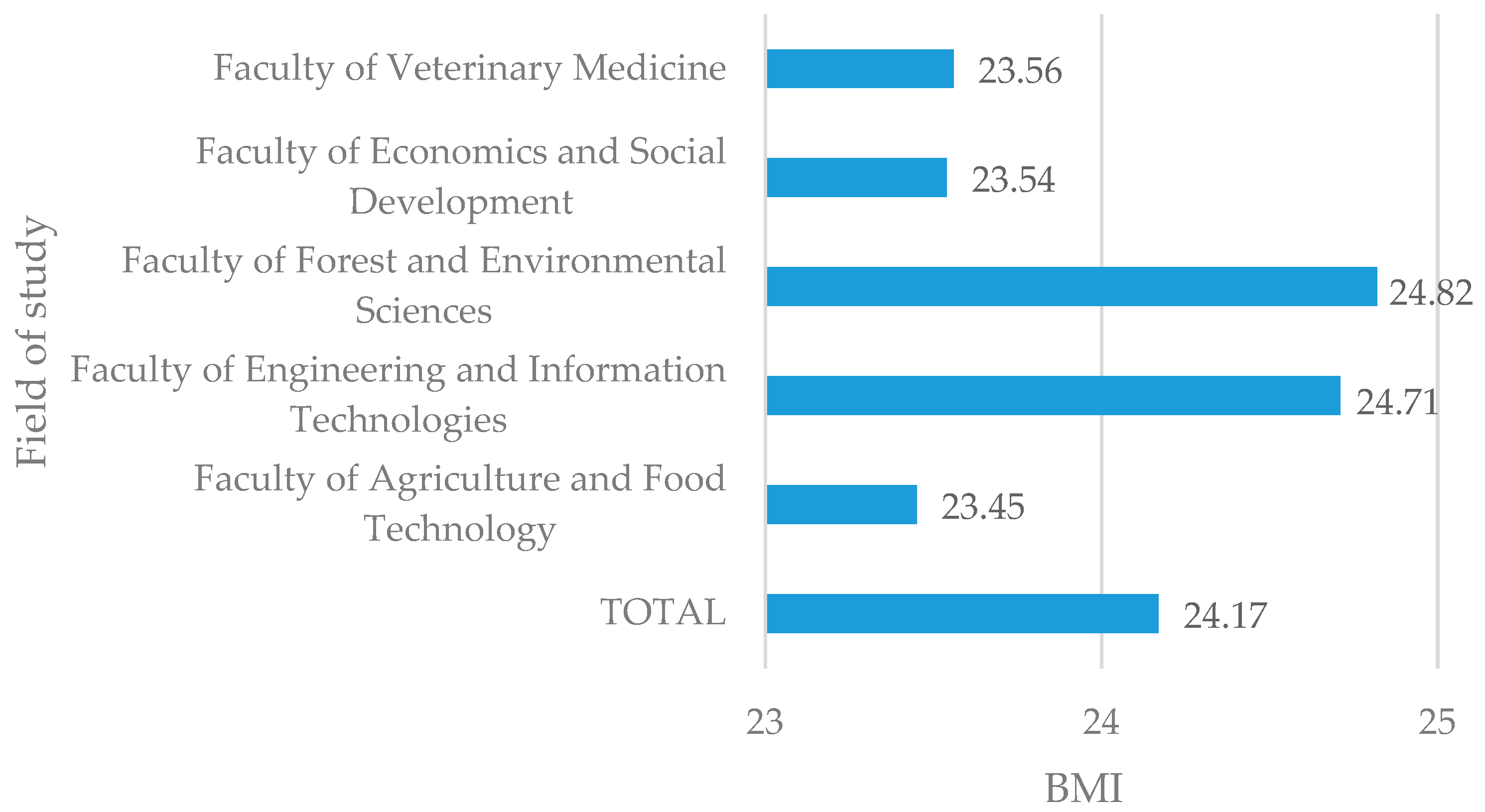

| The field of study | Faculty of Agriculture and Food Technology | 66 | 16.6 |

| Faculty of Engineering and Information Technologies | 98 | 24.7 | |

| Faculty of Forest and Environmental Sciences | 110 | 27.7 | |

| Faculty of Economics and Social Development | 64 | 16.1 | |

| Faculty of Veterinary Medicine | 59 | 14.9 | |

| BMI (total) | Underweight | 27 | 6.8 |

| Healthy weight | 238 | 59.9 | |

| Overweight | 85 | 21.4 | |

| Obesity | 47 | 11.8 | |

| Average Score ± SD | Min Value | Max Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

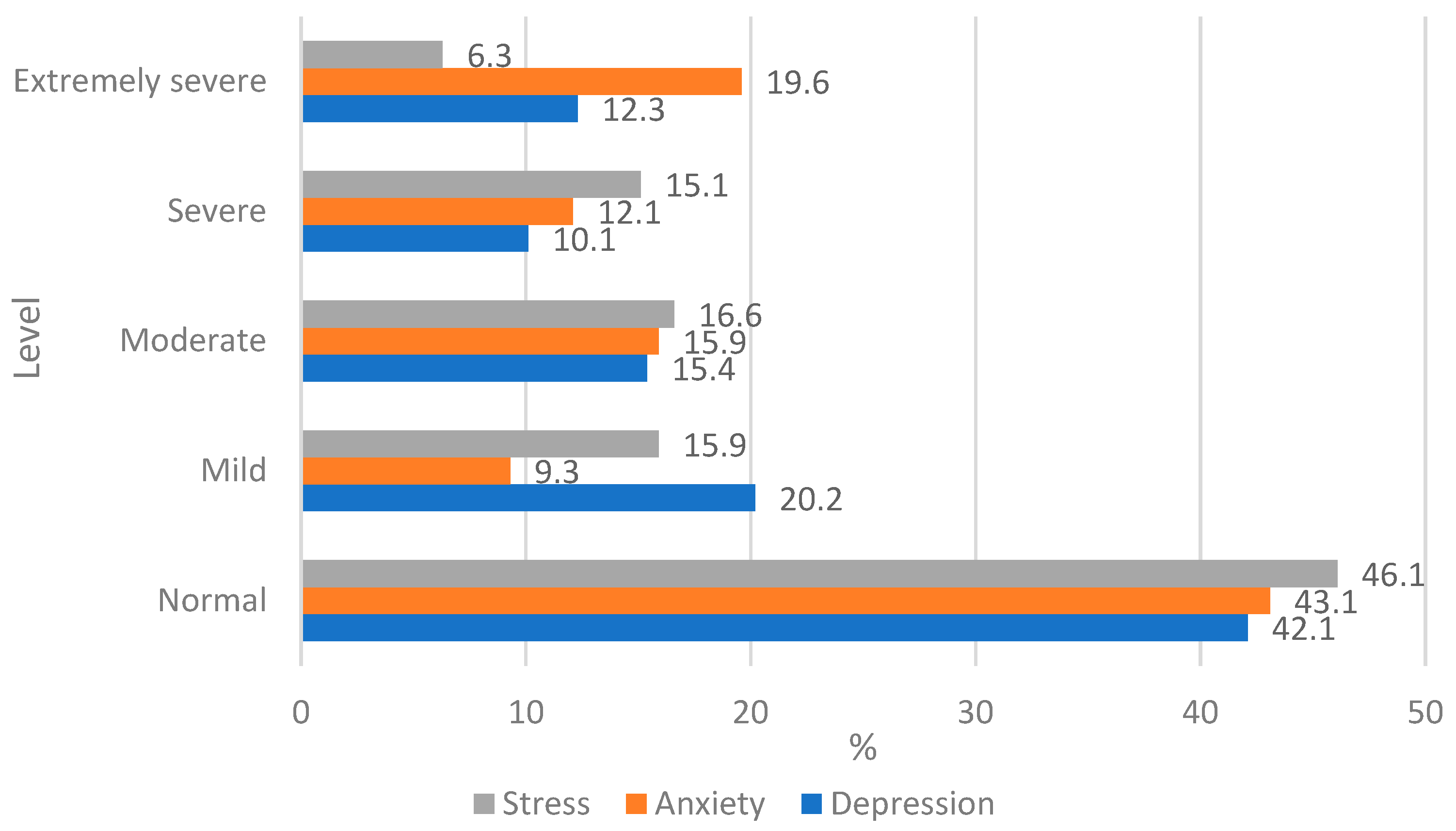

| Depression | |||

| Total | 13.49 ± 10.10 | 0 | 42.00 |

| Faculty of Agriculture and Food Technology | 13.92 ± 10.53 a | 0 | 41.00 |

| Faculty of Engineering and Information Technologies | 14.27 ± 10.25 a | 0 | 42.00 |

| Faculty of Forest and Environmental Sciences | 12.49 ± 10.18 a | 0 | 42.00 |

| Faculty of Economics and Social Development | 12.47 ± 9.59 a | 1.00 | 40.00 |

| Faculty of Veterinary Medicine | 14.69 ± 9.83 a | 1.00 | 37.00 |

| Anxiety | |||

| Total | 11.24 ± 8.90 | 0 | 39.00 |

| Faculty of Agriculture and Food Technology | 12.64 ± 9.67 a | 1.00 | 39.00 |

| Faculty of Engineering and Information Technologies | 10.88 ± 8.42 a,b | 0 | 35.00 |

| Faculty of Forest and Environmental Sciences | 9.73 ± 8.54 b | 0 | 39.00 |

| Faculty of Economics and Social Development | 11.44 ± 8.81 a | 1.00 | 38.00 |

| Faculty of Veterinary Medicine | 12.90 ± 9.26 a | 0 | 35.00 |

| Stress | |||

| Total | 16.47 ± 9.96 | 0 | 42.00 |

| Faculty of Agriculture and Food Technology | 17.58 ± 10.19 a,b | 0 | 39.00 |

| Faculty of Engineering and Information Technologies | 15.33 ± 9.07 c | 0 | 35.00 |

| Faculty of Forest and Environmental Sciences | 12.49 ± 10.18 d | 0 | 42.00 |

| Faculty of Economics and Social Development | 17.05 ± 10.41 b,c | 3.00 | 41.00 |

| Faculty of Veterinary Medicine | 19.56 ± 10.09 a | 0 | 39.00 |

| Average Score ± SD | Min Value | Max Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled eating | |||

| Total | 43.72 ± 14.69 | 18.52 | 81.48 |

| Faculty of Agriculture and Food Technology | 43.94 ± 15.41 a | 18.52 | 77.78 |

| Faculty of Engineering and Information Technologies | 42.36 ± 15.34 a | 18.52 | 81.48 |

| Faculty of Forest and Environmental Sciences | 46.16 ± 13.43 a | 22.22 | 81.48 |

| Faculty of Economics and Social Development | 37.96 ± 10.60 b | 18.52 | 59.26 |

| Faculty of Veterinary Medicine | 47.39 ± 16.98 a | 22.22 | 77.78 |

| Cognitive restraint | |||

| Total | 32.86 ± 30.58 | 0 | 100 |

| Faculty of Agriculture and Food Technology | 38.55 ± 32.45 a | 0 | 100 |

| Faculty of Engineering and Information Technologies | 31.06 ± 30.89 a | 0 | 100 |

| Faculty of Forest and Environmental Sciences | 32.22 ± 29.41 a | 0 | 100 |

| Faculty of Economics and Social Development | 30.90 ± 27.18 a | 0 | 88.89 |

| Faculty of Veterinary Medicine | 32.77 ± 31.68 a | 0 | 100 |

| Emotional eating | |||

| Total | 31.14 ± 29.00 | 0 | 100 |

| Faculty of Agriculture and Food Technology | 35.01±31.68 a | 0 | 100 |

| Faculty of Engineering and Information Technologies | 30.84 ± 29.87 a | 0 | 100 |

| Faculty of Forest and Environmental Sciences | 30.40 ± 26.24 a | 0 | 94.44 |

| Faculty of Economics and Social Development | 19.53 ± 18.73 b | 0 | 77.78 |

| Faculty of Veterinary Medicine | 42.24 ± 32.80 a | 0 | 94.44 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | |||

| Total | 11.01 ± 3.03 | 5.50 | 21.00 |

| Faculty of Agriculture and Food Technology | 10.53 ± 3.18 a | 6.00 | 21.00 |

| Faculty of Engineering and Information Technologies | 11.48 ± 3.13 a | 6.00 | 19.00 |

| Faculty of Forest and Environmental Sciences | 11.04 ± 2.84 a | 6.50 | 20.50 |

| Faculty of Economics and Social Development | 10.47 ± 2.87 a | 5.50 | 17.50 |

| Faculty of Veterinary Medicine | 11.32 ± 3.13 a | 6.50 | 21.00 |

| BMI | PSQI | DASS-42 | R18V2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Anxiety | Stress | UE | CR | EE | ||||

| BMI | Coefficient | - | |||||||

| p | - | ||||||||

| PSQI | Coefficient | 0.039 | - | ||||||

| p | >0.05 | - | |||||||

| Depression | Coefficient | 0.027 | 0.508 | - | |||||

| p | >0.05 | <0.01 | - | ||||||

| Anxiety | Coefficient | −0.105 | 0.490 | 0.642 | - | ||||

| p | <0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 | - | |||||

| Stress | Coefficient | −0.046 | 0.466 | 0.694 | 0.832 | - | |||

| p | >0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | - | ||||

| UE | Coefficient | 0.084 | 0.102 | 0.113 | 0.117 | 0.111 | - | ||

| p | >0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | - | |||

| CR | Coefficient | 0.266 | 0.034 | 0.077 | 0.066 | 0.092 | 0.280 | - | |

| p | <0.01 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | <0.01 | - | ||

| EE | Coefficient | 0.159 | 0.109 | 0.189 | 0.182 | 0.193 | 0.636 | 0.315 | - |

| p | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Priede, L.; Beitane, I.; Beitane, L. A Study of Relationships Between Mental Well-Being, Sleep Quality, Eating Behavior, and BMI: A Cross-Sectional Study Among University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101465

Priede L, Beitane I, Beitane L. A Study of Relationships Between Mental Well-Being, Sleep Quality, Eating Behavior, and BMI: A Cross-Sectional Study Among University Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(10):1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101465

Chicago/Turabian StylePriede, Linda, Ilze Beitane, and Loreta Beitane. 2025. "A Study of Relationships Between Mental Well-Being, Sleep Quality, Eating Behavior, and BMI: A Cross-Sectional Study Among University Students" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 10: 1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101465

APA StylePriede, L., Beitane, I., & Beitane, L. (2025). A Study of Relationships Between Mental Well-Being, Sleep Quality, Eating Behavior, and BMI: A Cross-Sectional Study Among University Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(10), 1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22101465