The Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire 3 (BREQ-3) Is Reliable and Valid for Assessing Motivational Regulations and Self-Determination in Exercise Among Adults Aged 50 Years or Older: A Methodological Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piercy, K.L.; Troiano, R.P.; Ballard, R.M.; Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Galuska, D.A.; George, S.M.; Olson, R.D. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Jama 2018, 320, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strain, T.; Flaxman, S.; Guthold, R.; Semenova, E.; Cowan, M.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C.; Stevens, G.A.; Abdul Raheem, R.; Agoudavi, K.; et al. National, regional, and global trends in insufficient physical activity among adults from 2000 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 507 population-based surveys with 5·7 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e1232–e1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.R.; Tong, A.; Howard, K.; Sherrington, C.; Ferreira, P.H.; Pinto, R.Z.; Ferreira, M.L. Older people’s perspectives on participation in physical activity: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiteri, K.; Broom, D.; Bekhet, A.; Xerri de Caro, J.; Laventure, B.; Grafton, K. Barriers and Motivators of Physical Activity Participation in Middle-Aged and Older Adults—A Systematic Review. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 27, 1–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 756. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, E.; Markland, D.; Ingledew, D.K. A graded conceptualisation of self-determination in the regulation of exercise behaviour: Development of a measure using confirmatory factor analytic procedures. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1997, 23, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markland, D.; Tobin, V.A. A modification to the Behavioural Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire to include an assessment of amotivation. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2004, 26, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.M.; Rodgers, W.M.; Loitz, C.C.; Scime, G. “It’s Who I Am…Really!” The Importance of Integrated Regulation in Exercise Contexts. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2006, 11, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, D.; Sofiati, S. Tradução e validação psicométrica do Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire para uso em adultos brasileiros. RBAFS 2015, 20, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slatyer, S.; Toye, C.; Burton, E.; Jacinto, A.F.; Hill, K.D. Measurement properties of self-report instruments to assess health literacy in older adults: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 2241–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, E.; Kafchinski, M.; Vrazel, J.; Sullivan, P. Motivators, barriers, and beliefs regarding physical activity in an older adult population. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2011, 34, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baert, V.; Gorus, E.; Mets, T.; Geerts, C.; Bautmans, I. Motivators and barriers for physical activity in the oldest old: A systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011, 10, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Stralen, M.M.; De Vries, H.; Mudde, A.N.; Bolman, C.; Lechner, L. Determinants of initiation and maintenance of physical activity among older adults: A literature review. Health Psychol. Rev. 2009, 3, 147–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.E.; Reis, R.S.; Sallis, J.F.; Wells, J.C.; Loos, R.J.; Martin, B.W. Correlates of physical activity: Why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 2012, 380, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palombi, T.; Lucidi, F.; Chirico, A.; Alessandri, G.; Filosa, L.; Tavolucci, S.; Borghi, A.M.; Fini, C.; Cavicchiolo, E.; Pistella, J.; et al. Is the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire a Valid Measure in Older People? Healthcare 2023, 11, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brucki, S.M.; Nitrini, R.; Caramelli, P.; Bertolucci, P.H.; Okamoto, I.H. Suggestions for utilization of the mini-mental state examination in Brazil. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2003, 61, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil; Ministry of Health; Secretariat of Health Care; Department of Primary Care. Guidelines for the Collection and Analysis of Anthropometric Data in Health Services: Technical Standard of the Food and Nutrition Surveillance System-SISVAN; Série G. Statistics and Health Information; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 2011; 76p, ISBN 978-85-334-1813-4. Available online: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/orientacoes_coleta_analise_dados_antropometricos.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Fess, E.; Moran, C. American Society of Hand Therapists Clinical Assessment Recommendations; American Society of Hand Therapists: Mount Laurel, NJ, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, H.C.; Denison, H.J.; Martin, H.J.; Patel, H.P.; Syddall, H.; Cooper, C.; Sayer, A.A. A review of the measurement of grip strength in clinical and epidemiological studies: Towards a standardised approach. Age Ageing 2011, 40, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treacy, D.; Hassett, L. The Short Physical Performance Battery. J. Physiother. 2018, 64, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guralnik, J.M.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Glynn, R.J.; Berkman, L.F.; Blazer, D.G.; Scherr, P.A.; Wallace, R.B. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J. Gerontol. 1994, 49, M85–M94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guralnik, J.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Pieper, C.F.; Leveille, S.G.; Markides, K.S.; Ostir, G.V.; Studenski, S.; Berkman, L.F.; Wallace, R.B. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: Consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2000, 55, M221–M231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Wang, Y.C. Four-Meter Gait Speed: Normative Values and Reliability Determined for Adults Participating in the NIH Toolbox Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, K.D.; Shafer, A.B. Validity and Reliability of the Polar A300’s Fitness Test Feature to Predict VO2max. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2019, 12, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.L.; Neri, A.L.; Ferrioli, E.; Lourenço, R.A.; Dias, R.C. Phenotype of frailty: The influence of each item in determining frailty in community-dwelling elderly—The Fibra Study. Cien Saude Colet. 2016, 21, 3483–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleiss, J.L.; Levin, B.; Paik, M.C. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.; de Boer, M.R.; Van der Windt, D.A.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Study Design Checklist for Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Instruments. Available online: https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-study-designing-checklist_final.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- Hulley, S.B.; Cummings, S.R.; Browner, W.S.; Grady, D.G.; Newman, T.B. Delineando a Pesquisa Clínica, 4th ed.; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brasil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cid, L.; Monteiro, D.; Teixeira, D.; Teques, P.; Alves, S.; Moutão, J.; Silva, M.; Palmeira, A. The Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire (BREQ-3) Portuguese-Version: Evidence of Reliability, Validity and Invariance Across Gender. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Mullin, E.M.; Mellano, K.T.; Sha, Y.; Wang, C. Examining the psychometric properties of the Chinese Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire-3: A bi-factor approach. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cutre, D.; Sicilia, Á.; Fernández, A. Toward a deeper understanding of motivation towards exercise: Measurement of integrated regulation in the Spanish context. Psicothema 2010, 22, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cavicchiolo, E.; Sibilio, M.; Lucidi, F.; Cozzolino, M.; Chirico, A.; Girelli, L.; Manganelli, S.; Giancamilli, F.; Galli, F.; Diotaiuti, P.; et al. The Psychometric Properties of the Behavioural Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire (BREQ-3): Factorial Structure, Invariance and Validity in the Italian Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenthal, K.M. An Introduction to Psychological Tests and Scales; UCL Press Limited: London, UK, 1996; p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, R.; Probst, M.; Bastos, T.; Vilhena, E.; Seabra, A.; Corredeira, R. Behavioural Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire in people with schizophrenia: Construct validity of the Portuguese versions. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 2577–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Videm, V.; Hoff, M.; Liff, M.H. Use of the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire-2 to assess motivation for physical activity in persons with rheumatoid arthritis: An observational study. Rheumatol. Int. 2022, 42, 2039–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Xiang, M.; Guo, H.; Sun, Z.; Wu, T.; Liu, H. Reliability and Validity of the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire-2 for Nursing Home Residents in China. Asian Nurs Res 2020, 14, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 2008, 49, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Dai, J.; Liu, J. An integrative perspective of validating a simplified Chinese version behavioral regulation in exercise questionnaire-2. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2018, 22, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murcia, J.A.; Gimeno, E.C.; Camacho, A.M. Measuring self-determination motivation in a physical fitness setting: Validation of the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire-2 (BREQ-2) in a Spanish sample. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2007, 47, 366–374. [Google Scholar]

- Karloh, M.; Araujo, J.; Silva, I.J.C.S.; Alexandre, H.F.; Barbosa, G.B.; Munari, A.B.; Gulart, A.A.; Mayer, A.F. Is the Behavioural Regulation In Exercise Questionnaire-2 (BREQ-2) valid and reliable for motivational assessment in pulmonary rehabilitation? Assobrafir Cienc. 2022, (Suppl. S1), 209. [Google Scholar]

- Portney, L.G. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice, 4th ed.; F.A. Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Carvas Junior, N.; Gomes, I.C.; Valassi, J.M.R.; Anunciação, L.; Freitas-Dias, R.; Koike, M.K. Comparison of the printed and online administration of the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire (BREQ-2). Einstein 2021, 19, eAO6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foxman, B. Determining the Reliability and Validity and Interpretation of a Measure in the Study Populations. Mol. Tools Infect. Dis. Epidemiol. 2012, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustaka, F.; Vlachopoulos, S.; Vazou, S.; Kaperoni, M.; Markland, D. Initial Validity Evidence for the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire-2 Among Greek Exercise Participants. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 26, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmanbar, R.; Niknami, S.; Hidarnia, A.; Lubans, D.R. Psychometric Properties of the Iranian Version of the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire-2 (BREQ-2). Health Promot. Perspect. 2011, 1, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karloh, M.; Sousa Matias, T.; Fleig Mayer, A. The COVID-19 Pandemic Confronts the Motivation Fallacy within Pulmonary Rehabilitation Programs. Copd 2020, 17, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matias, T.; Dominski, F.H.; Marks, D.F. Human needs in COVID-19 isolation. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Reliability Study (n = 80) | Validation Study (n = 136) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 62.8 ± 8.0 | 65.5 ± 8.0 |

| Sex * | ||

| Female | 58 (72.5) | 104 (76.5) |

| Male | 22 (27.5) | 32 (23.5) |

| Body mass, kg | 70.7 ± 13.8 | 70.1 ± 12.3 |

| Height, m | 1.60 ± 0.92 | 1.60 ± 0.93 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.4 ± 4.16 | 27.3 ± 3.42 |

| Handgrip Strength, kgf | 24.9 ± 8.6 | 25.3 ± 7.08 |

| Handgrip weakness | ||

| Yes | 26 (32.5) | 34 (25) |

| No | 54 (67.5) | 102 (75) |

| SPPB * | ||

| Very poor | 3 (3.8) | 4 (2.9) |

| Poor | 22 (27.5) | 41 (30.1) |

| Moderate | 55 (68.8) | 91 (66.9) |

| Good | - | - |

| 4-Meter Gait Speed Test, s | 3.29 ± 0.99 | 3.17 ± 0.93 |

| 4-Meter Gait Speed Test, m/s | 0.82 ± 0.24 | 0.79 ± 0.23 |

| Cardiovascular fitness | 25.6 ± 6.29 | 28.7 ± 6.96 |

| Frailty | ||

| Non-frail | 24 (30) | 24 (17.6) |

| Pre-frail | 43 (53.8) | 92 (67.6) |

| Frail | 13 (16.4) | 20 (14.7) |

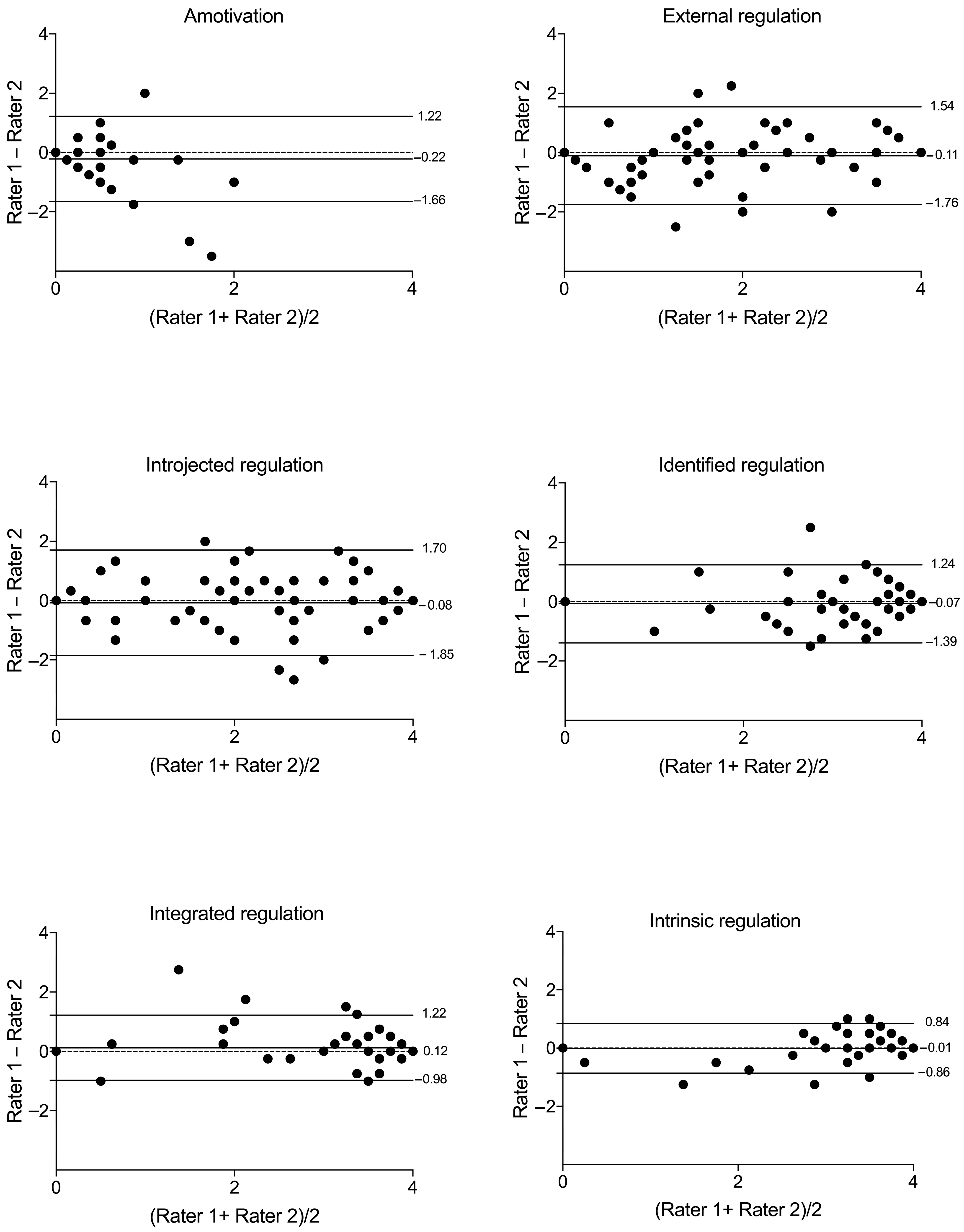

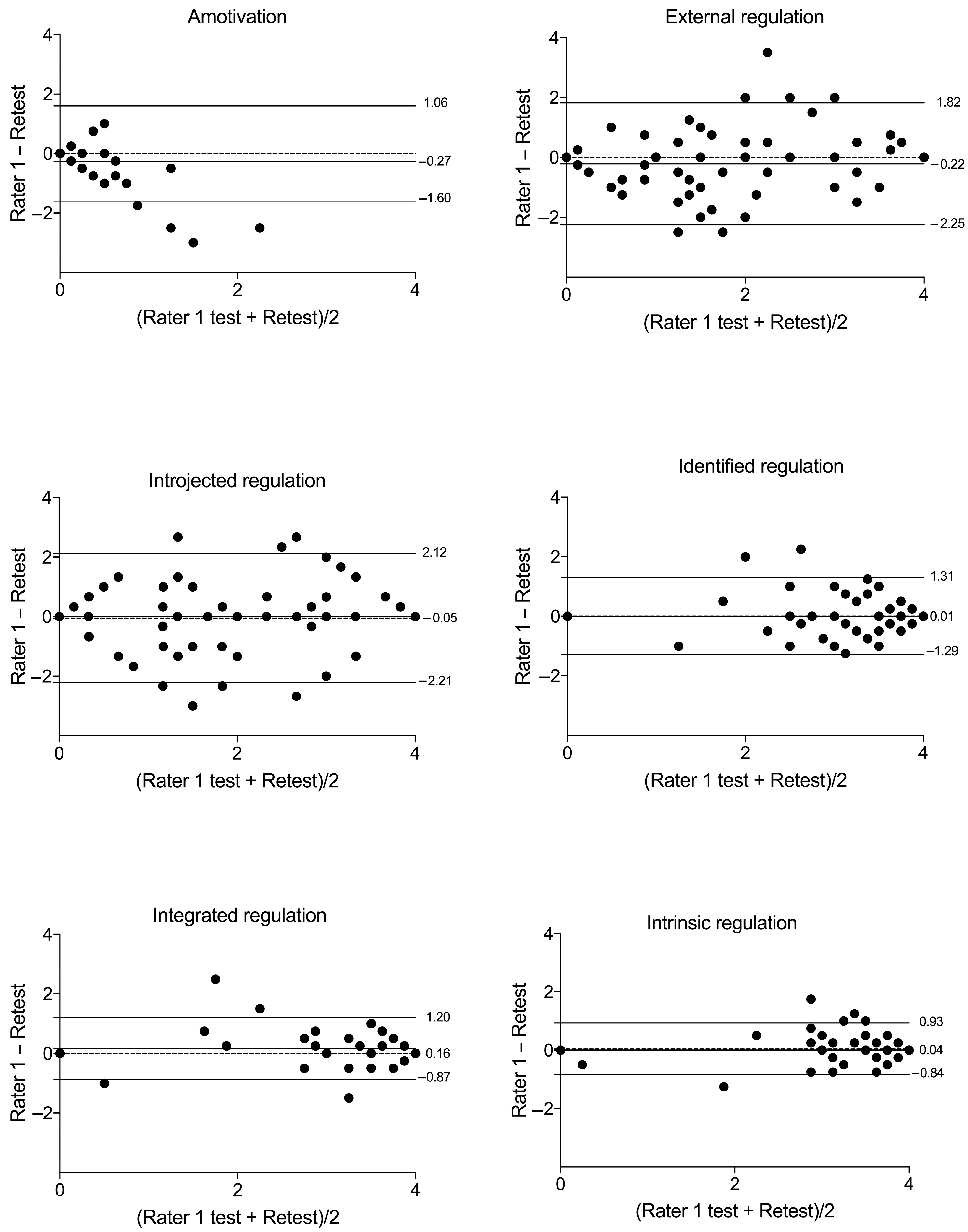

| BREQ-3 | Evaluator 1 Mean ± SD | Evaluator 1 Retest Mean ± SD | Evaluator 2 Mean ± SD | Test-Retest ICC (95% CI) | Inter-Rater ICC (95% CI) | Cronbach’s α | SEM | MDC95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amotivation | 0.28 ± 0.57 | 0.15 ± 0.32 | 0.17 ± 0.38 | 0.25 (−0.12–0.50) | 0.25 (−0.14–0.51) | 0.61 | 0.59 | 1.63 |

| External regulation | 1.47 ± 0.91 | 1.33 ± 1.01 | 1.40 ± 1.06 | 0.77 (0.64–0.85) | 0.87 (0.80–0.92) | 0.60 | 0.53 | 1.47 |

| Introjected regulation | 1.59 ± 1.47 | 1.54 ± 1.55 | 1.61 ± 1.40 | 0.83 (0.74–0.89) | 0.88 (0.81–0.92) | 0.72 | 0.56 | 1.54 |

| Identified regulation | 3.36 ± 0.64 | 3.36 ± 0.68 | 3.27 ± 0.72 | 0.79 (0.68–0.87) | 0.80 (0.68–0.87) | 0.55 | 0.35 | 0.98 |

| Integrated regulation | 2.79 ± 1.12 | 2.90 ± 1.13 | 2.92 ± 1.10 | 0.91 (0.85–0.94) | 0.89 (0.83–0.93) | 0.82 | 0.34 | 0.80 |

| Intrinsic regulation | 3.30 ± 0.75 | 3.32 ± 0.79 | 3.27 ± 0.84 | 0.90 (0.85–0.94) | 0.92 (0.88–0.95) | 0.77 | 0.32 | 0.64 |

| SDI | 13.43 ± 4.86 | 14.43 ± 4.48 | 14.00 ± 5.07 | 0.82 (0.68–0.89) | 0.88 (0.81–0.93) | 0.75 | 2.55 | 7.06 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | SDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Amotivation | 1 | 0.16 | −0.08 | −0.22 * | −0.38 * | −0.18 | −0.59 ** |

| 2. External | - | 1 | 0.37 * | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.01 | −0.64 ** |

| 3. Introjected | - | - | 1 | 0.41 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.40 ** | −0.20 |

| 4. Identified | - | - | - | 1 | 0.39 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.29 * |

| 5. Integrated | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.51 ** | 0.47 ** |

| 6. Intrinsic | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.42 ** |

| SDI | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Non-Frail (n = 23) | Pre-Frail (n = 92) | Frail (n = 18) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amotivation | 0.21 ± 0.48 | 0.28 ± 0.53 | 0.35 ± 0.82 | 0.55 |

| External | 1.48 ± 0.98 | 1.45 ± 0.87 | 1.57 ± 1.00 | 0.71 |

| Introjected | 2.25 ± 1.21 * | 1.39 ± 1.41 | 2.04 ± 1.74 | 0.04 |

| Identified | 3.53 ± 0.51 | 3.34 ± 0.65 | 3.30 ± 0.73 | 0.41 |

| Integrated | 3.68 ± 0.58 *† | 2.60 ± 1.11 | 2.69 ± 1.20 | <0.01 |

| Intrinsic | 3.72 ± 0.38 *† | 3.18 ± 0.81 | 3.33 ± 0.63 | <0.01 |

| SDI | 16.2 ± 4.38 *† | 12.9 ± 4.54 | 12.5 ± 5.96 | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Oliveira Vanini, J.; Karloh, M.; Coelho Bosco, R.; de Souza, M.G.; Karsten, M.; Matte, D.L. The Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire 3 (BREQ-3) Is Reliable and Valid for Assessing Motivational Regulations and Self-Determination in Exercise Among Adults Aged 50 Years or Older: A Methodological Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010082

de Oliveira Vanini J, Karloh M, Coelho Bosco R, de Souza MG, Karsten M, Matte DL. The Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire 3 (BREQ-3) Is Reliable and Valid for Assessing Motivational Regulations and Self-Determination in Exercise Among Adults Aged 50 Years or Older: A Methodological Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(1):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010082

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Oliveira Vanini, Jacyara, Manuela Karloh, Ricardo Coelho Bosco, Michelle Gonçalves de Souza, Marlus Karsten, and Darlan Laurício Matte. 2025. "The Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire 3 (BREQ-3) Is Reliable and Valid for Assessing Motivational Regulations and Self-Determination in Exercise Among Adults Aged 50 Years or Older: A Methodological Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 1: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010082

APA Stylede Oliveira Vanini, J., Karloh, M., Coelho Bosco, R., de Souza, M. G., Karsten, M., & Matte, D. L. (2025). The Brazilian Portuguese Version of the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire 3 (BREQ-3) Is Reliable and Valid for Assessing Motivational Regulations and Self-Determination in Exercise Among Adults Aged 50 Years or Older: A Methodological Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010082