Interpersonal Perfectionism and Perceived Control’s Influence on the Continuity of Sports Practice in Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Behavioral Intention

1.2. Perceptions of Social Pressure

1.3. Perceived Control

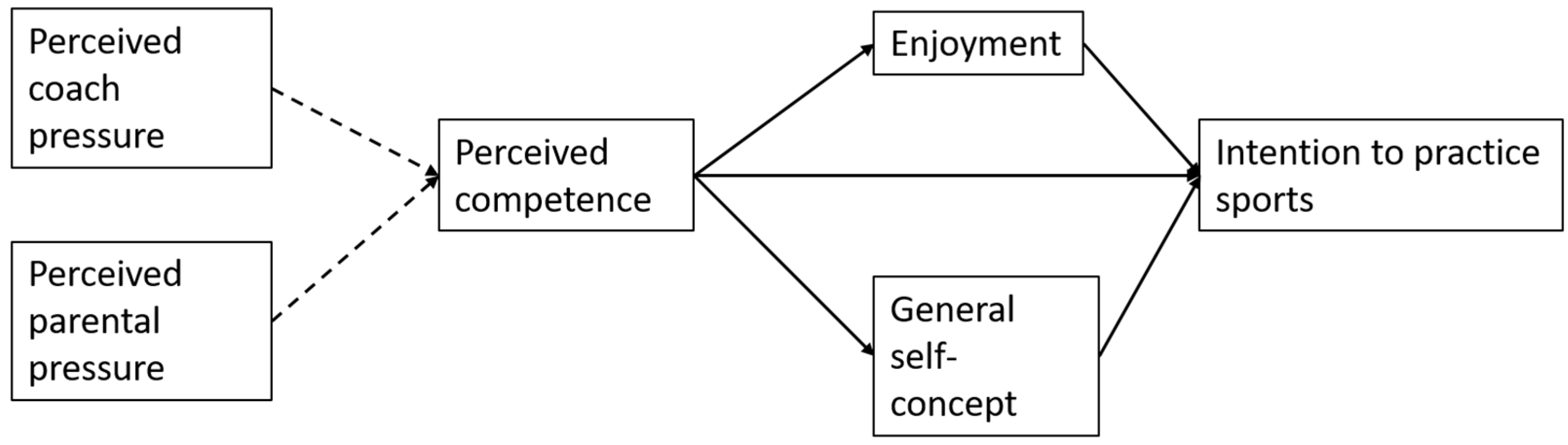

1.4. Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Sample

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

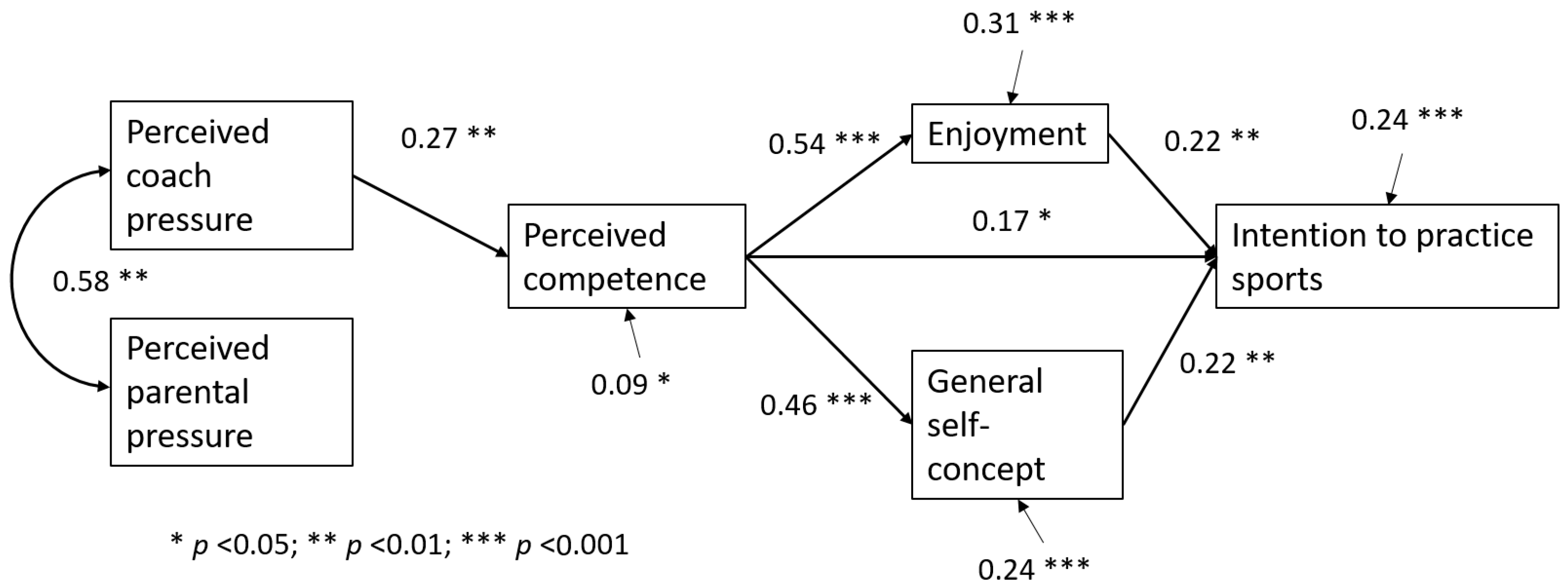

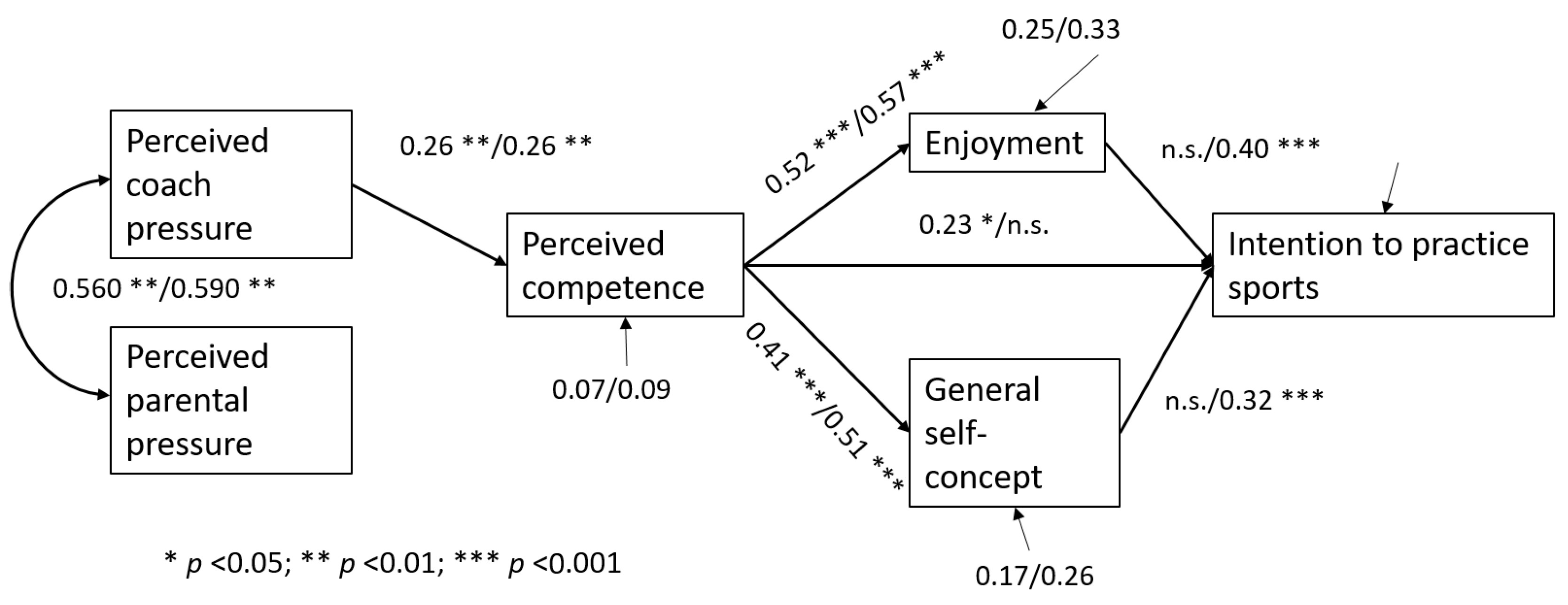

3.2. Primary Analysis

3.3. Indirect Effects

4. Discussion

5. Practical Implications

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heredia-León, D.A.; Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Gómez-Mármol, A.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Prediction of the adherence to sports practice of young Ecuadorians based on the perception of the coach’s interpersonal style. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1133583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinero, O.; Martínez, R.; Garatachea, N.; Márquez, S. Pautas de actividad física de adolescentes españolas: Diferencias medidas por el día de la semana y la participación deportiva. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2011, 19, 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M.; Lohmann, S.; Albarracín, D. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In The Handbook of Attitudes, Volume 1: Basic Principles; Albarraciny, D., Johnson, B.T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 197–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Mao, L. Influence of the adaptive perfectionism and autonomous motivation on adolescents’ exercise adherence: Moderating effect of parental autonomy support. J. Shanghai Univ. Sport 2020, 44, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huéscar, E.; Andrés, J.A.; Moreno-Murcia, J.A. Effect of autonomy support and dialogic learning on school children’s physical activity and sport. Scand. J. Psychol. 2020, 61, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The tehory of planed behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Martin Fishbein’s legacy: The reasoned action approach. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2012, 640, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour is alive and well, and not ready to retire: A commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau, and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 9, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Changing behavior using the theory of planned behavior. In The Handbook of Behavior Change; Hagger, M.S., Cameron, L.D., Hamilton, K., Hankoneny, N., Intunen, T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B. Crafting normative messages to protect the environment. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 12, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Cohn, M.A. Positive emotions. In Handbook of Emotions, 3rd ed.; Lewis, M., Haviland-Jonesy, J.M., Feldman, L., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 777–796. [Google Scholar]

- Porto, L.; Krapp do Nascimento, R.; Milistetd, M.; Vieira do Nascimento, J.; Folle, A. Revisión sistemática de las influencias sociales en el deporte: Apoyo de la familia, entrenadores y compañeros de equipo. Apunt. Educ. Fis. Deport. 2021, 37, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, T.S.; Horn, J.L. Family influences on children’s sport and physical activity participation, behaviour, and psychosocial responses. In Handbook of Sport Psychology, 3rd ed.; Tenenbaumy, G., Eklund, R.C., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 685–711. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, S.; Garrido, M.E.; Zagalaz, M.L. El comportamiento de los padres en el deporte. Retos Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2009, 15, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunomura, M.; Oliveira, M.S. Parents’ support in the sports career of young gymnasts. Sci. Gymnast. J. 2013, 5, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ames, C. The relationship of achievement goals to student motivation in classroom settings. In Motivation in Sport and Exercise; Roberts, G.C., Ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1992; pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, A.P. Perfectionism myths. In Motivation and Self-Regulation in Sport and Exercise; Englerty, C., Taylor, I., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, P.L.; Flett, G.L. Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnar, D.S.; Reker, D.L.; Culp, N.A.; Sadava, S.W.; DeCourville, N.H. A mediated model of perfectionism, affect, and physical health. J. Res. Pers. 2006, 40, 482–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Otto, K. Positive conceptions of perfectionism: Approaches, evidence, challenges. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 10, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flett, G.L.; Hewitt, P.L.; Oliver, J.M.; Macdonald, S. Perfectionism in children and their parents: A developmental analysis. In Perfectionism: Theory, Research, and Treatment; Flett, G.L., Hewitt, P.L., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 89–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.G.; Dunn, J.C.; Syrotuik, D.G. Relationship between multidimensional perfectionism and goal orientations in sport. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2002, 24, 376–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior; Dorsey Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Roa, A. La educación emocional, el autoconcepto, la autoestima y su importancia en la infancia. Edetania 2013, 44, 241–257. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, J.A.; Moreno, R.; Cervelló, E. El autoconcepto físico como predictor de la intención de ser físicamente activo. Psicol. Salud 2007, 17, 261–267. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas, R.; Contreras, O.; Fernández, J.G.; González-Martí, I. Influencia de la motivación y el autoconcepto físico sobre la intención de ser físicamente activo. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2014, 31, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hassandra, M.; Vlachopoulos, S.P.; Kosmidou, E.; Hatzigeorgiadis, A.; Goudas, M.; Theodorakis, Y. Predicting students’ intention to smoke by theory of planned behaviour variables and parental influences across school grade levels. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1241–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.B.; Yin, Z.; Hanes, J.; Duda, J.; Gutin, B.; Barbeau, P. Measuring Enjoyment of Physical Activity in Children: Validation of the Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2009, 21, S116–S129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.-A.; González-Cutre, D.; Martínez, C.; Alonso, N.; López, M. Propiedades psicométricas de la Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) en el contexto español. Stud. Psychol. 2008, 29, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Armitage, C.J. Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 1429–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ato, M.; López, J.J.; Benavente, A. A classification system for research designs in psychology. An. Psicol. 2013, 9, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Hadaya, P. Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 227–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda-Espejel, H.A.; Morquecho-Sánchez, R.; Gadea-Cavazos, E. Evidencias de validez test-criterio en el uso de la Escala Multidimensional de Perfeccionismo en el Deporte-2. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2018, 18, 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda-Espejel, H.A.; Arrayales, E.; Castro, S.; Morquecho, A.; Trejo, M.; Fernández, R. Versión en español de la subescala presión del entrenador del MIPS: Propiedades psicométricas. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2018, 8, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escartí, A.; Gutiérrez, M. Influence of the motivational climate in physical education on the intention to practice physical activity or sport. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2001, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingles, C.J.; Torregrosa, M.S.; Hidalgo, M.D.; Nuñez, J.C.; Castejón, J.L.; García-Fernández, J.M.; Valle, A. Validity evidence based on internal structure of scores on the Spanish version of the self-description questionnaire-II. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.-T.; Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) Findings. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2004, 11, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; MacKinnon, D.P. Resampling and distribution of the product methods for testing indirect effects in complex models. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2008, 15, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P.L.; Flett, G.L.; Mikail, S.F. Perfectionism: A Relational Approach to Conceptualization, Assessment, and Treatment; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Madigan, D.J.; Curran, T.; Stoeber, J.; Hill, A.P.; Smith, M.M.; Passfield, L. Development of perfectionism in junior athletes: A three-sample study of coach and parental pressure. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2019, 41, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsch, T.E.; Smith, A.L.; Dotterer, A.M. Individual, relationship, and context factors associated with parent support and pressure in organized youth sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 23, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuerth, S.; Lee, M.; Alfermann, D. Parental involvement and athletes’ career in youth sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2004, 5, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.D.; Di Paula, A. Perfectionistic self-beliefs: Their relation to personality and goal pursuit. In Perfectionism; Flett, G.L., Hewitt, P.L., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- Stoeber, J.; Childs, J.H. The Assessment of self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism: Subscales make a difference. J. Pers. Assess. 2010, 92, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, P.R.; Curran, T. The origins of perfectionism in sport, dance, and exercise: An introduction to the conceptual model of perfectionism development. In The Psychology of Perfectionism in Sport, Dance and Exercise; Hill, A.P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chamero, C.; Fraile, J. Relación del disfrute en la actividad físico-deportiva con la autoeficacia motriz percibida al final de la infancia. Qurriculum Rev. Teoría Investig. Práctica Educ. 2013, 26, 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hellín, P.; Moreno, J.A.; Rodríguez, P.L. Relación de la competencia motriz percibida con la práctica físico-deportiva. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2006, 15, 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, M.R.; Amorose, A.J.; Wilko, A.M. Coaching behaviors, motivational climate, and psychosocial outcomes among female adolescent athletes. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2009, 21, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Battista, R.; Robazza, C.; Ruiz, M.C.; Bertollo, M.; Vitali, F.; Bortoli, L. Student intention to engage in leisure-time physical activity: The interplay of task-involving climate, competence need satisfaction and psychobiosocial states in physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 761–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grao-Cruces, A.; Fernández-Martínez, A.; Teva-Villén, M.R.; Nuviala, A. Autoconcepto físico e intencionalidad para ser físicamente activo en los participantes del programa escuelas deportivas. J. Sport Health Res. 2017, 9, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, D.S.; Pelletier, L.G.; Monteiro, D.; Rodrigues, F.; Moutão, J.; Marinho, D.A.; Cid, L. Motivational patterns in persistent swimmers: A serial mediation analysis. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2019, 20, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, L.A.; Magee, C.A.; Vella, S.A. Social climate profiles in adolescent sports: Associations with enjoyment and intention to continue. J. Adolesc. 2016, 52, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozkowitz, J.T.; Folkman, S.; Acree, M. Do positive psychological states shed light on recovery from bereavement? Findings from a 3-year longitudinal study. Death Stud. 2003, 27, 471–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crane, J.; Temple, V. A systematic review of dropout from organized sport among children and youth. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2015, 21, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, R.R.; Baranowski, T.; Dowda, M.; Trost, S.G. Tracking of physical activity in young children. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1996, 28, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huotari, P.; Nupponen, H.; Mikkelsson, L.; Laakso, L.; Kujala, U. Adolescent physical fitness and activity as predictors of adulthood activity. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamberg, S. Applying the stage model of self-regulated behavioral change in a car use reduction intervention. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 33, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sport | Age Mean (SD) | Boys (n) | Girls (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| American football | 14.72 (0.40) | 25 | 0 |

| Soccer football | 14.02 (0.35) | 34 | 10 |

| Swimming | 14.06 (0.48) | 16 | 16 |

| Volleyball | 14.26 (0.81) | 0 | 54 |

| Athletics | 14.08 (0.06) | 12 | 28 |

| Instrument | χ2 (Sig.) | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPP subscale of S-MPS-2 | 64.19 (p < 0.001) | 24 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.08 (0.06–1.00) | 0.05 |

| PCP subscale of MIPS | 39.65 (p < 0.001) | 17 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.05 (0.04–0.09) | 0.03 |

| Perceived competence and enjoyment subscales of IMI | 43.92 (p < 0.001) | 13 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.07 (0.01–0.09) | 0.03 |

| General self-concept subscale of SDQ-II | 14.42 (p < 0.001) | 5 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.04 (0.03–0.05) | 0.03 |

| MIFA | 11.1 (p < 0.001) | 5 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.07 (0.01–0.09) | 0.03 |

| PCP | PPP | Perceived Competence | Enjoyment | General Self-Concept | Intention to Practice Sports | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCP | 0.94 | |||||

| PPP | 0.35 ** | 0.94 | ||||

| Perceived competence | 0.23 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.90 | |||

| Enjoyment | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.54 ** | 0.95 | ||

| General self-concept | 0.10 | 0.34 ** | 0.46 ** | −0.01 | 0.95 | |

| Intention to practice sports | 0.26 ** | 0.13 | 0.40 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.90 |

| Range | 1–6 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–6 | 1–5 |

| M | 3.10 | 2.48 | 3.90 | 4.65 | 4.30 | 4.28 |

| SD | 1.23 | 0.094 | 0.94 | 0.52 | 1.07 | 0.83 |

| Model | χ2 (df) | p | RMSEA | ΔRMSEA | CFI | ΔCFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | 14.98 (5) | 0.035 | 0.08 | 0.95 | ||

| Girls | 13.99 (5) | 0.020 | 0.07 | 0.94 | ||

| Unconstrained | 19.22 (14) | 0.044 | 0.981 | |||

| Structural weights | 26.95 (21) | 0.35 | 0.038 | 0.006 | 0.978 | 0.003 |

| Structural covariances | 27.85 (24) | 0.82 | 0.029 | 0.015 | 0.986 | 0.005 |

| Structural residuals | 36.44 (28) | 0.07 | 0.040 | 0.004 | 0.969 | 0.012 |

| Precedent/Mediator | Outcome | a | SE | b | SE | Product Term ab | 95% CI Upper | 95% CI Lower |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived competence/enjoyment | Intention to practice sports | 0.54 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.22 |

| Perceived competence/self-concept | Intention to practice sports | 0.46 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pineda-Espejel, H.A. Interpersonal Perfectionism and Perceived Control’s Influence on the Continuity of Sports Practice in Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010070

Pineda-Espejel HA. Interpersonal Perfectionism and Perceived Control’s Influence on the Continuity of Sports Practice in Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(1):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010070

Chicago/Turabian StylePineda-Espejel, H. Antonio. 2025. "Interpersonal Perfectionism and Perceived Control’s Influence on the Continuity of Sports Practice in Adolescents" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 1: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010070

APA StylePineda-Espejel, H. A. (2025). Interpersonal Perfectionism and Perceived Control’s Influence on the Continuity of Sports Practice in Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010070