Implementation Outcomes and Recommendations of Two Physical Activity Interventions: Results from the Danish ACTIVE SCHOOL Feasibility Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Schools and Participants

2.3. The Interventions

2.3.1. Run, Jump & Fun Intervention

2.3.2. Move & Learn Intervention

2.4. Procedures and Measures

2.4.1. Quantitative Measures

2.4.2. Statistics

2.4.3. Qualitative Data

2.4.4. Analysis of Qualitative Data

3. Results

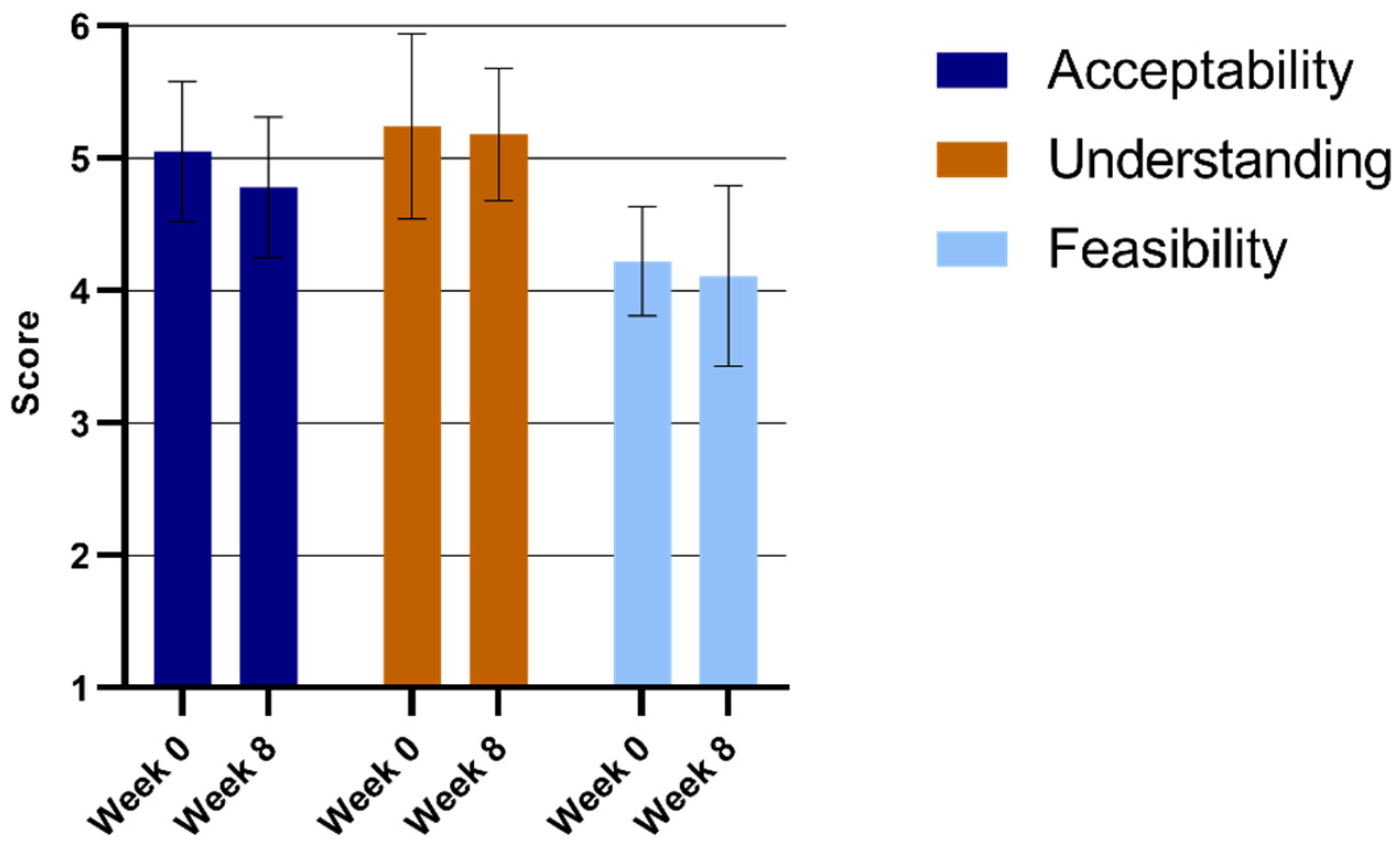

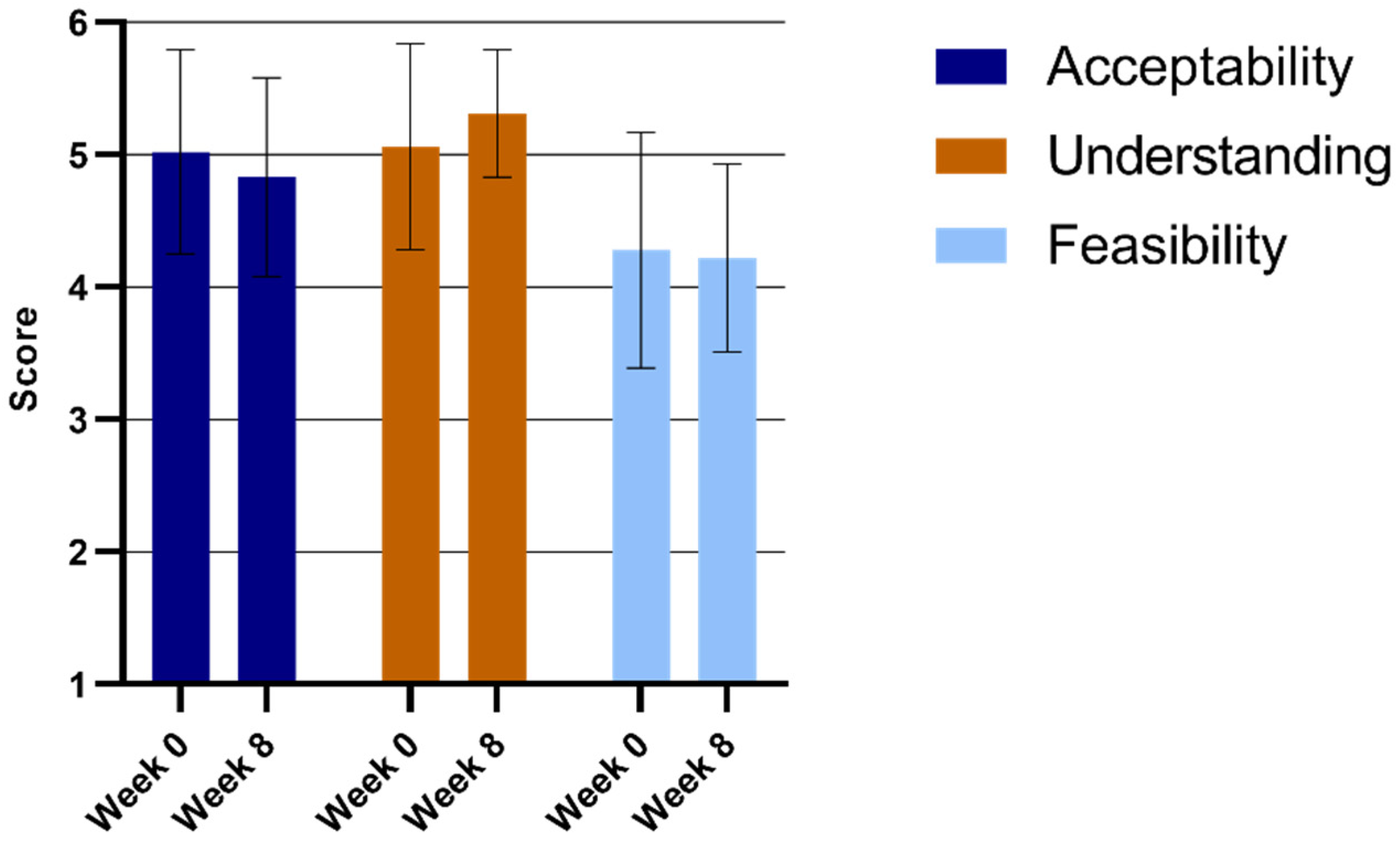

3.1. Acceptability, Understanding, and Feasibility

3.1.1. Run, Jump & Fun

“…it takes a long time to do, I think. Both in terms of preparation and execution. Maybe longer than I thought”(School 3, Teacher 2)

“What we did (in the courses, ed.) was very concrete. It was something we could take home and bring into the classroom right away or just use on the playground. So, it was a good bank of ideas to take home, if you were completely blank. I mean, before you went on the course…”(School 5, Teacher 2)

3.1.2. Move & Learn

“I found the second part (of the courses at the school) to be helpful… to hear the introduction to this mindset of Move & Learn, with the attached elements. I cannot remember it by heart, but I have the didactic tool and principles on my desk, and it is a way of thinking that I need to incorporate in my teaching”(School 4, Teacher 1)

“So, it has been great to be challenged to think about it in a new way and to be confirmed that, well, I can actually do it when encountering another topic. It would normally be easier just to follow the pupils’ book”(School 6, Teacher 2)

“As soon as I start, they know what it is about. Then it just runs smoothly. It has been really inspiring”(School 7, Teacher 2)

3.2. Appropriateness

3.2.1. Run, Jump & Fun

“So, I think it has worked well for me. However, I would have liked to have been able to better integrate it into the subjects”(School 1, Teacher 3)

3.2.2. Move & Learn

“It was a way for me to remind myself that it is also important to include movement when teaching 3rd grade.—That it is important to let them move around and get their bodies moving as well”(School 6, Teacher 2)

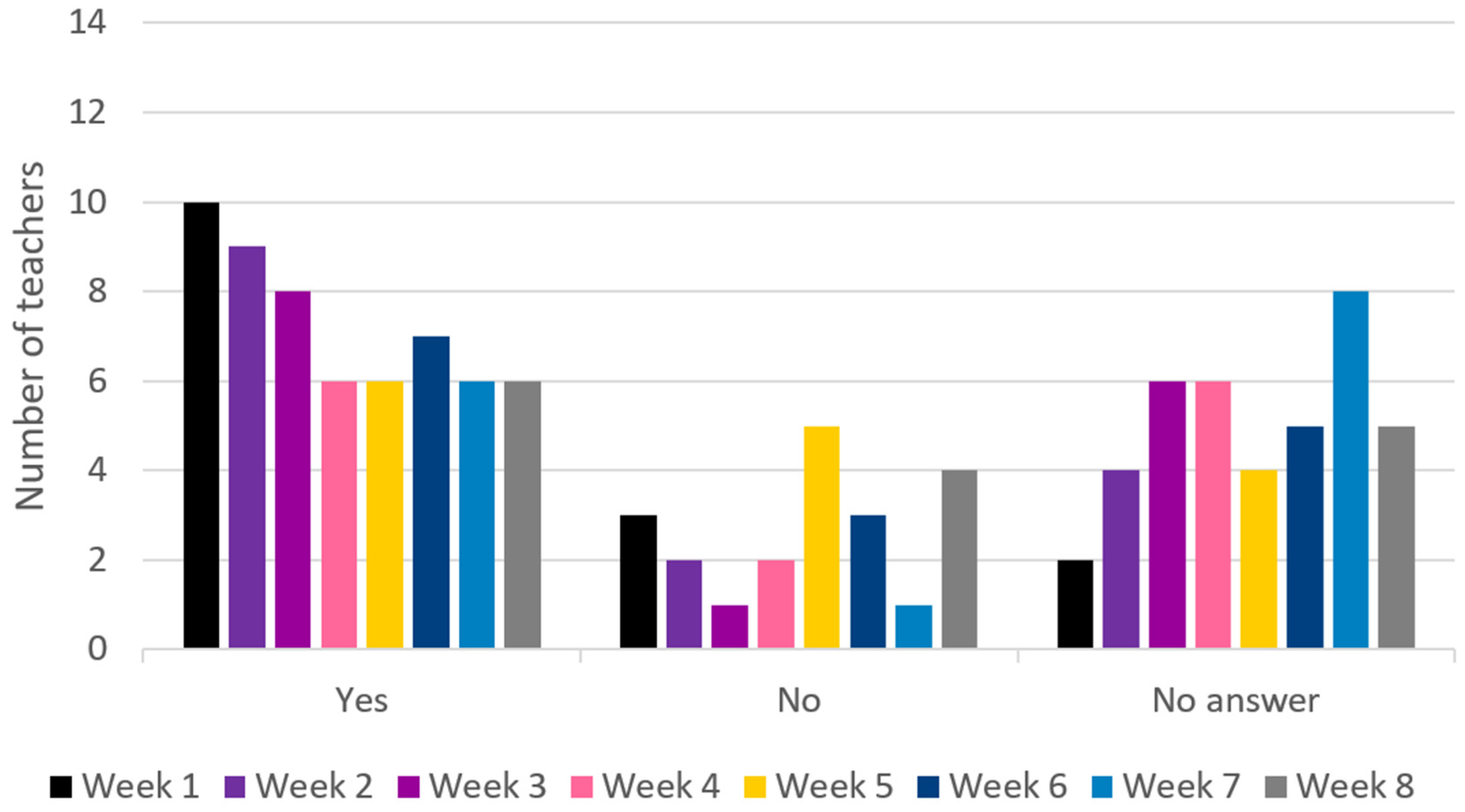

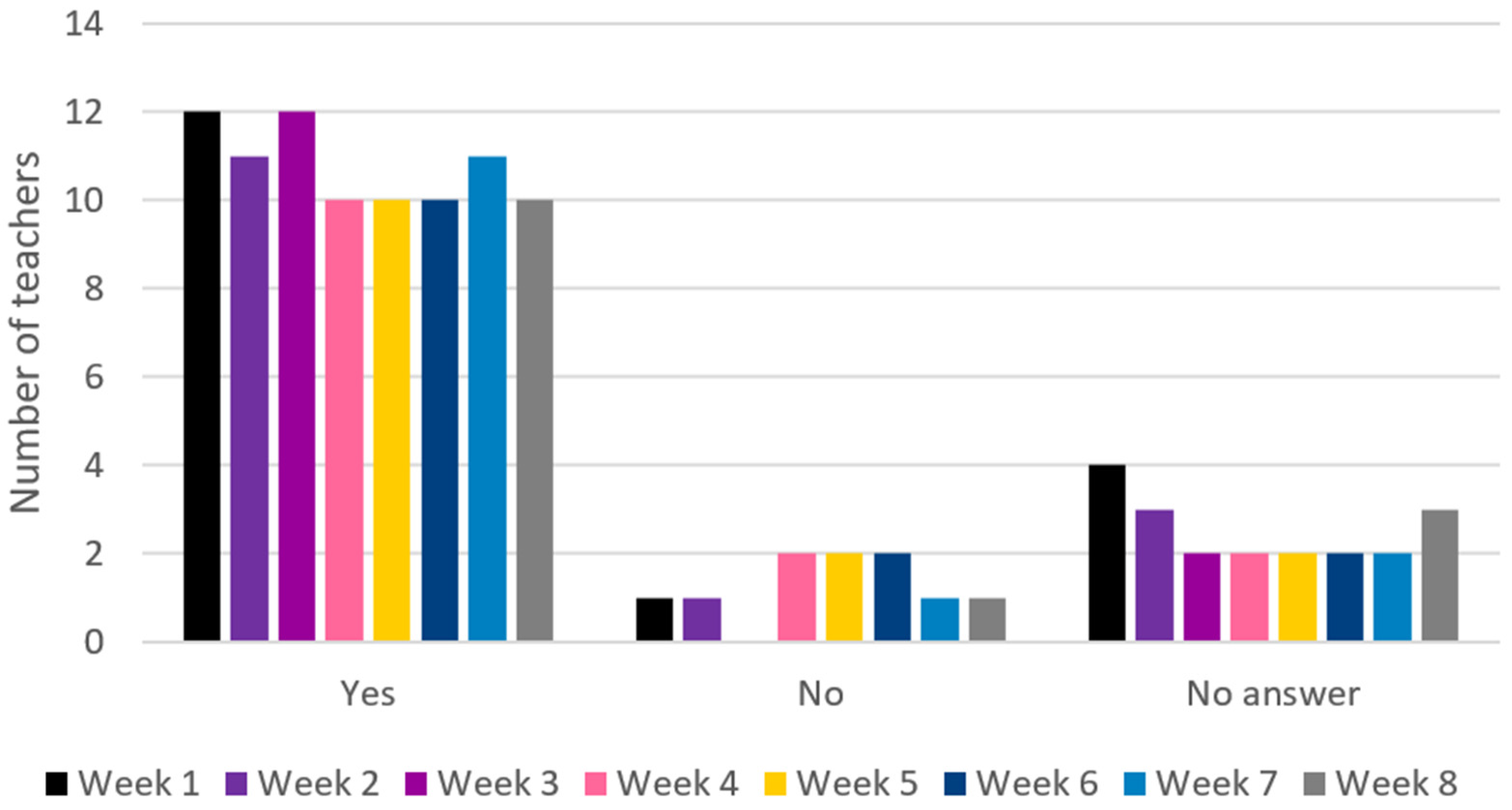

3.3. Implementation

3.3.1. Run, Jump & Fun

“It was not really about creating some advanced games and activities with all sorts of equipment; it was actually just about making it fun and involving to as many pupils as possible. They should be activated, raise their heart rate, and feel that they were a part of a community”(School 5, Teacher 4)

“So, we found some different music with power and in that way, we could easily go on for half an hour with the children”(School 5, Teacher 1)

3.3.2. Move & Learn

“What you [ACTIVE SCHOOL] are providing is both inspiring and the materials are comprehensive and excellent. However, it has been challenging for me to implement it with 3rd grade”(School 7, Teacher 1)

“…I have, to a large extent, received tons of good ideas and have been able to work on them myself. I have also been given tools for it, like how we think it ourselves, without having it served to us. It has been so fantastic…much better than I dared to hope for”(School 7, Teacher 3)

4. Discussion

4.1. Antecedent Assessments

4.1.1. Understanding

4.1.2. Acceptability

4.1.3. Appropriateness

4.2. Implementation Outcomes

4.2.1. Adoption

4.2.2. Fidelity

4.3. Recommendations and Implications

- The personnel required to implement an intervention must be defined in the early stages and the workforce in schools must be taken into account [71]. Intervention providers must clearly define and inform school leaders about the time required in teachers’ yearly time allocation, without compromising other mandatory tasks. Importantly, an agreement on the total amount of time allocated for the project should be formalized in a contract.

- Courses to foster adoption must ideally be provided in several sessions, particularly when the intervention covers a complete school year, in order to support teachers’ gradual development in implementing a PA intervention [72]. Practical engagement and demonstrations must be highly prioritized over theory.

- For school-based PAL or embodied learning interventions, it is important to communicate the long-term perspective of the interventions. Planning and re-thinking teaching for embodied learning is a step-by-step process and ongoing practice leads to self-confidence and routine [54,73]. Further, for these types of interventions, attention to a specific intensity can be replaced by attention to a movement-centered approach, where the intervention entails learning activities with the body which are widely integrated into the learning process [73].

- To avoid mixing when there is more than one intervention type in the same study, there must be a clear distinction between these interventions in all communications, especially in exemplary course activities.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFIR OAD | Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Outcomes Addendum Diagram |

| ML | ‘Move & Learn’ intervention |

| MVPA | Moderate to vigorous Physical activity |

| PA | Physical activity |

| PAL | Physically Active Learning |

| PE | Physical Education |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| RJF | ‘Run, Jump & Fun’ intervention |

| SMS | Short Message Service |

| URP-I | Usage Rating Profile-Intervention |

References

- Janssen, I.; LeBlanc, A.G. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.; Fedewa, A.L. A Meta-analysis of the Relationship Between Children’s Physical Activity and Mental Health. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2011, 36, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shao, W. Influence of Sports Activities on Prosocial Behavior of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Wu, L.; Ming, Q. How Does Physical Activity Intervention Improve Self-Esteem and Self-Concept in Children and Adolescents? Evidence from a Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.S.; Saliasi, E.; van den Berg, V.; Uijtdewilligen, L.; de Groot, R.H.M.; Jolles, J.; Andersen, L.B.; Bailey, R.; Chang, Y.-K.; Diamond, A.; et al. Effects of physical activity interventions on cognitive and academic performance in children and adolescents: A novel combination of a systematic review and recommendations from an expert panel. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedewa, A.L.; Ahn, S. The Effects of Physical Activity and Physical Fitness on Children’s Achievement and Cognitive Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2011, 82, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Hillman, C.H.; Etnier, J.L.; Lee, S.; Tomporowski, P.; Lambourne, K.; Szabo-reed, A. Physical Activity, Fitness, Cognitive Function, and Academic Achievement in Children: A Systematic Review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1197–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.A.; Zarrett, N.; Cook, B.S.; Egan, C.; Nesbitt, D.; Weaver, R.G. Movement integration in elementary classrooms: Teacher perceptions and implications for program planning. Eval. Program Plann. 2017, 61, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulimeno, M.; Piscitelli, P.; Colazzo, S.; Colao, A.; Miani, A. School as ideal setting to promote health and wellbeing among young people. Health Promot. Perspect. 2020, 10, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, P.-J.; Mckay, H.A. Prevention in the first place: Schools a setting for action on physical inactivity. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelid, M.B. Approaching physically active learning as a multi, inter, and transdisciplinary research field. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1228340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Stralen, M.M.; Yıldırım, M.; Wulp, A.; te Velde, S.J.; Verloigne, M.; Doessegger, A.; Androutsos, O.; Kovács, É.; Brug, J.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. Measured sedentary time and physical activity during the school day of European 10- to 12-year-old children: The ENERGY project. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2014, 17, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nettlefold, L.; McKay, H.A.; Warburton, D.E.R.; McGuire, K.A.; Bredin, S.S.D.; Naylor, P.J. The challenge of low physical activity during the school day: At recess, lunch and in physical education. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salin, K.; Huhtiniemi, M.; Watt, A.; Hakonen, H.; Jaakkola, T. Differences in the Physical Activity, Sedentary Time, and BMI of Finnish Grade 5 Students. J. Phys. Act. Health 2019, 16, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Pesce, C.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Sánchez-López, M.; Garrido-Miguel, M.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Academic Achievement and Physical Activity: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20171498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavilidi, M.F.; Pesce, C.; Benzing, V.; Schmidt, M.; Paas, F.; Okely, A.D.; Vazou, S. Meta-analysis of movement-based interventions to aid academic and behavioral outcomes: A taxonomy of relevance and integration. Educ. Res. Rev. 2022, 37, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubans, D.; Richards, J.; Hillman, C.; Faulkner, G.; Beauchamp, M.; Nilsson, M.; Kelly, P.; Smith, J.; Raine, L.; Biddle, S. Physical Activity for Cognitive and Mental Health in Youth: A Systematic Review of Mechanisms. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Hillman, C.H.; Castelli, D.; Etnier, J.L.; Lee, S.; Tomporowski, P.; Lambourne, K.; Szabo-Reed, A.N. Physical activity, fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children: A systematic review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1223–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J. BRAIN BOOST—How Sport and Physical Activity Enhance Children’s Learning What the Research Is Telling Us. Government of Western Australia, Department of Sport and Recreation/Curtin University, Western Australia, November 2015. Available online: https://www.dlgsc.wa.gov.au/docs/default-source/sport-and-recreation/brain-boost---how-sport-and-physical-activity-enhance-childrens-learning.pdf?sfvrsn=c9c8f9d1_1 (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Hillman, C.H.; Pontifex, M.B.; Castelli, D.M.; Khan, N.A.; Raine, L.B.; Scudder, M.R.; Drollette, E.S.; Moore, R.D.; Wu, C.-T.; Kamijo, K. Effects of the FITKids Randomized Controlled Trial on Executive Control and Brain Function. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e1063–e1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.L.; Tomporowski, P.D.; McDowell, J.E.; Austin, B.P.; Miller, P.H.; Yanasak, N.E.; Allison, J.D.; Naglieri, J.A. Exercise improves executive function and achievement and alters brain activation in overweight children: A randomized, controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2011, 30, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavilidi, M.F.; Ruiter, M.; Schmidt, M.; Okely, A.D.; Loyens, S.; Chandler, P.; Paas, F. A Narrative Review of School-Based Physical Activity for Enhancing Cognition and Learning: The Importance of Relevancy and Integration. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulmowski, A.; Rey, G.D. Embodied learning: Introducing a taxonomy based on bodily engagement and task integration. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2018, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavilidi, M.F.; Lubans, D.R.; Miller, A.; Eather, N.; Morgan, P.J.; Lonsdale, C.; Noetel, M.; Karayanidis, F.; Shaw, K.; Riley, N. Impact of the “Thinking while Moving in English” intervention on primary school children’s academic outcomes and physical activity: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 102, 101592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Benzing, V.; Wallman-Jones, A.; Mavilidi, M.-F.; Lubans, D.R.; Paas, F. Embodied learning in the classroom: Effects on primary school children’s attention and foreign language vocabulary learning. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 43, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, K.L.; Aggerholm, K.; Jensen, J.-O. Enactive movement integration: Results from an action research project. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 95, 103139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S.; Lindgren, R. Enactive metaphors: Learning through full-body engagement. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 27, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, L.; Stolz, S.A. Embodied cognition and its significance for education. Theory Res. Educ. 2019, 17, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errisuriz, V.L.; Dooley, E.E.; Burford, K.G.; Johnson, A.M.; Jowers, E.M.; Bartholomew, J.B. Implementation Quality Impacts Fourth Grade Students’ Participation in Physically Active Academic Lessons. Prev. Sci. 2021, 22, 950–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.M.; Elliott, S.J. It’s not as Easy as just Saying 20 Minutes a Day’: Exploring Teacher and Principal Experiences Implementing a Provincial Physical Activity Policy. Univers. J. Public Health 2015, 3, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly-Smith, A.; Quarmby, T.; Archbold, V.S.J.; Routen, A.C.; Morris, J.L.; Gammon, C.; Bartholomew, J.B.; Resaland, G.K.; Llewellyn, B.; Allman, R.; et al. Implementing physically active learning: Future directions for research, policy, and practice. J. Sport health Sci. 2020, 9, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solberg, R.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Anderssen, S.A.; Ekelund, U.; Säfvenbom, R.; Haugen, T.; Berntsen, S.; Åvitsland, A.; Lerum, Ø.; Resaland, G.K.; et al. Effects of a school-based physical activity intervention on academic performance in 14-year old adolescents: A cluster randomized controlled trial—The School in Motion study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Hillman, C.H.; Greene, J.L.; Hansen, D.M.; Gibson, C.A.; Sullivan, D.K.; Poggio, J.; Mayo, M.S.; Lambourne, K.; Szabo-Reed, A.N.; et al. Physical activity and academic achievement across the curriculum: Results from a 3-year cluster-randomized trial. Prev. Med. 2017, 99, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavilidi, M.; Lubans, D.; Eather, N.; Morgan, P.; Riley, N. Preliminary Efficacy and Feasibility of “Thinking While Moving in English”: A Program with Physical Activity Integrated into Primary School English Lessons. Children 2018, 5, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, C.A.; Russ, L.; Vazou, S.; Goh, T.L.; Erwin, H. Integrating movement in academic classrooms: Understanding, applying and advancing the knowledge base. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazou, S.; Webster, C.A.; Stewart, G.; Candal, P.; Egan, C.A.; Pennell, A.; Russ, L.B. A Systematic Review and Qualitative Synthesis Resulting in a Typology of Elementary Classroom Movement Integration Interventions. Sport Med-Open 2020, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullender-Wijnsma, M.J.; Hartman, E.; de Greeff, J.W.; Doolaard, S.; Bosker, R.J.; Visscher, C. Physically Active Math and Language Lessons Improve Academic Achievement: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20152743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullender-Wijnsma, M.J.; Hartman, E.; de Greeff, J.W.; Bosker, R.J.; Doolaard, S.; Visscher, C. Moderate-to-vigorous physically active academic lessons and academic engagement in children with and without a social disadvantage: A within subject experimental design. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Bengoechea, E.; Woods, C.B.; Murtagh, E.; Grady, C.; Fabre, N.; Lhuisset, L.; Zunquin, G.; Aibar, A.; Zaragoza Casterad, J.; Haerens, L.; et al. Rethinking Schools as a Setting for Physical Activity Promotion in the 21st Century–a Position Paper of the Working Group of the 2PASS 4Health Project. Quest 2024, 76, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohl Jeppesen, L.; Bugge, A.; Smedegaard, S.; Wienecke, J.; Sandfeld Melcher, J. Developing ACTIVE SCHOOL—The Design Process of Two School-Based Physical Activity Interventions No Title. Transl. J. Am. Coll. Sport. Med. 2024, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs—Principles and Practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skamagki, G.; King, A.; Carpenter, C.; Wåhlin, C. The concept of integration in mixed methods research: A step-by-step guide using an example study in physiotherapy. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2022, 40, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Opra Widerquist, M.A.; Lowery, J. Conceptualizing outcomes for use with the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): The CFIR Outcomes Addendum. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; DuPre, E.P. Implementation Matters: A Review of Research on the Influence of Implementation on Program Outcomes and the Factors Affecting Implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solberg, R.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Ekelund, U.; Lerum, Ø.; Åvitsland, A.; Haugen, T.; Berntsen, S.; Kolle, E. Effect Of A School-based Physical Activity Intervention On Academic Performance In Norwegian Adolescents: The School In Motion Study—A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2020, 52, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briesch, A.M.; Chafouleas, S.M.; Neugebauer, S.R.; Riley-Tillman, T.C. Assessing influences on intervention implementation: Revision of the Usage Rating Profile-Intervention. J. Sch. Psychol. 2013, 51, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsborg, P.; Melby, P.S.; Kurtzhals, M.; Tremblay, M.S.; Nielsen, G.; Bentsen, P. Translation and validation of the Canadian assessment of physical literacy-2 in a Danish sample. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://study.sagepub.com/thematicanalysis (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Koorts, H.; Eakin, E.; Estabrooks, P.; Timperio, A.; Salmon, J.; Bauman, A. Implementation and scale up of population physical activity interventions for clinical and community settings: The PRACTIS guide. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly-Smith, A.; Morris, J.L.; Norris, E.; Williams, T.L.; Archbold, V.; Kallio, J.; Tammelin, T.H.; Singh, A.; Mota, J.; von Seelen, J.; et al. Behaviours that prompt primary school teachers to adopt and implement physically active learning: A meta synthesis of qualitative evidence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerum, Ø.; Bartholomew, J.; McKay, H.; Resaland, G.; Tjomsland, H.; Anderssen, S.; Leirhaug, P.; Moe, V. Active Smarter Teachers: Primary School Teachers’ Perceptions and Maintenance of a School-Based Physical Activity Intervention. Transl. J. Am. Coll. Sports Med. 2019, 4, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelid, M.B.; Resaland, G.K.; Lerum, Ø.; Teslo, S.; Chalkley, A.; Singh, A.; Bartholomew, J.; Daly-Smith, A.; Thurston, M.; Tjomsland, H.E. Unpacking physically active learning in education: A movement didaktikk approach in teaching? Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2024, 68, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerum, Ø.; Eikeland Tjomsland, H.; Leirhaug, P.E.; McKenna, J.; Quaramby, T.; Bartholomew, J.; Jenssen, E.S.; Smith, A.D.; Resaland, G.K. The Conforming, The Innovating and The Connecting Teacher: A qualitative study of why teachers in lower secondary school adopt physically active learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 105, 103434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skage, I.; Dyrstad, S.M. ‘It’s not because we don’t believe in it...’: Headteachers’ perceptions of implementing physically active lessons in school. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, N.; Elton, B.; Babic, M.; McCarthy, N.; Sutherland, R.; Presseau, J.; Seward, K.; Hodder, R.; Booth, D.; Yoong, S.L.; et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of physical activity policies in schools: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2018, 107, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahamed, Y.; Macdonald, H.; Reed, K.; Naylor, P.-J.; Liu-Ambrose, T.; Mckay, H. School-Based Physical Activity Does Not Compromise Children’s Academic Performance. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2007, 39, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangsbo, J.; Krustrup, P.; Duda, J.; Hillman, C.; Andersen, L.B.; Weiss, M.; Williams, C.A.; Lintunen, T.; Green, K.; Hansen, P.R.; et al. The Copenhagen Consensus Conference 2016: Children, youth, and physical activity in schools and during leisure time. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1177–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, A.; Whiting, S.; Simmonds, P.; Scotini Moreno, R.; Mendes, R.; Breda, J. Physical Activity and Academic Achievement: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The Association Between School Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance; Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–84. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/25616/cdc_25616_DS1.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Nielsen Have, J.; Rasmusen, M. Bevægelse i Skoledagen 2022. Nyborg, 2022. Available online: https://skoleidraet.dk/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/bevaegelse-i-skoledagen-2022.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Koch, S.; Pawlowski, C.S.; Skovgaard, T.; Pedersen, N.H.; Troelsen, J. Exploring implementation of a nationwide requirement to increase physical activity in the curriculum in Danish public schools: A mixed methods study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nassau, F.; Singh, A.S.; Broekhuizen, D.; van Mechelen, W.; Brug, J.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. Barriers and facilitators to the nationwide dissemination of the Dutch school-based obesity prevention programme DOiT. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Resaland, G.K.; Aadland, E.; Moe, V.F.; Aadland, K.N.; Skrede, T.; Stavnsbo, M.; Suominen, L.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Glosvik, Ø.; Andersen, J.R.; et al. Effects of physical activity on schoolchildren’s academic performance: The Active Smarter Kids (ASK) cluster-randomized controlled trial. Prev. Med. 2016, 91, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emonson, C.; Papadopoulos, N.; Rinehart, N.; Mantilla, A.; Fuelscher, I.; Boddy, L.M.; Pesce, C.; McGillivray, J. The feasibility and acceptability of a classroom-based physical activity program for children attending specialist schools: A mixed-methods pilot study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickman, L.; Riemer, M.; Brown, J.L.; Jones, S.M.; Flay, B.R.; Li, K.-K.; DuBois, D.; Pelham, W., Jr.; Massetti, G. Approaches to Measuring Implementation Fidelity in School-Based Program Evaluations. J. Res. Character Educ. 2009, 7, 75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, P.; Moore, B.; Boardman, A.G.; Arya, D.J.; Maul, A. Validating a Fidelity Scale to Understand Intervention Effects in Classroom-Based Studies. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 54, 1378–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillehoj, C.J.G.; Griffin, K.W.; Spoth, R. Program Provider and Observer Ratings of School-Based Preventive Intervention Implementation: Agreement and Relation to Youth Outcomes. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jago, R.; Salway, R.; House, D.; Beets, M.; Lubans, D.R.; Woods, C.; de Vocht, F. Rethinking children’s physical activity interventions at school: A new context-specific approach. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1149883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.; Troelsen, J.; Cassar, S.; Pawlowski, C.S. Barriers to Implementation of Physical Activity in Danish Public Schools. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2020, 40, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, A.R. Implementation Science and Practice in the Education Sector. Washington, 2017. Available online: https://education.uw.edu/sites/default/files/Implementation%20Science%20Issue%20Brief%20072617.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Daly-Smith, A.; Ottesen, C.L.; Mandelid, M.B.; von Seelen, J.; Trautner, N.; Resaland, G.K. The European Physical Active Learning Teacher Training Curriculum. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361426001_Activate_Curriculum_digital-1 (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Chalkley, A.E.; Mandelid, M.B.; Thurston, M.; Tjomsland, H.E.; Morris, J.L.; Kallio, J.; Archbold, V.S.J.; Resaland, G.K.; Daly-Smith, A. Finding the sweet spot of physically active learning: A need for co-ownership by public health and education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2024, 148, 104695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, P.-J.; Nettlefold, L.; Race, D.; Hoy, C.; Ashe, M.C.; Wharf Higgins, J.; McKay, H.A. Implementation of school based physical activity interventions: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2015, 72, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, K.; Cavill, N.; Chalkley, A.; Foster, C.; Gomersall, S.; Hagstromer, M.; Kelly, P.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.; Mair, J.; McLaughlin, M.; et al. Eight Investments That Work for Physical Activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 2021, 18, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasson, R.E.; Beemer, L.R.; Eisman, A.B.; Friday, P. Closing the Gap Between Classroom-Based Physical Activity Intervention Adoption and Fidelity in Low-Resource Schools. Kinesiol. Rev. 2023, 12, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, L.; Tyler, R.; Knowles, Z.; Ashworth, E.; Boddy, L.; Foweather, L.; Fairclough, S.J. Co-Creation of a School-Based Motor Competence and Mental Health Intervention: Move Well, Feel Good. Children 2023, 10, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escaron, A.L.; Vega-Herrera, C.; Martinez, C.; Steers, N.; Lara, M.; Hochman, M. Impact of a school-level intervention on leisure-time physical activity levels on school grounds in under-resourced school districts. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 22, 101377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohl Jeppesen, L.; Damsgaard, L.; Stolpe, M.N.; Melcher, J.N.S.; Wienecke, J.; Nielsen, G.; Smedegaard, S.; Henriksen, A.H.; Hansen, R.A.; Hillman, C.H.; et al. Study protocol for the ACTIVE SCHOOL study investigating two different strategies of physical activity to improve academic performance in Schoolchildren. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Source | Content | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Usage Rating Profile Intervention online survey | A 29-item self-report electronic questionnaire covering six indicators of adaptability and implementation of interventions. Five out of six subscales were included: (1) Acceptability, (2) Understanding, (3) Feasibility, (4) System Climate and (5) System Support. | A 6-point scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree. They were measured at week 0 before the pilot period, after the introduction course, and at week 8 (the end of the intervention). |

| Teacher post-intervention online survey | Custom quantitative (ratings) regarding adoption, feasibility, adoption, implementation and sustainability: For example: To which degree have you adopted the intervention? To what degree did the implementation strategies aid you? Qualitative (open-ended) questions, for example: Why were these strategies the most important to you? | A 6-point scale ranging from 1 = not at all to 6 = to a very high degree. Boxes in the survey where respondents could write further explanations for their quantitative ratings. |

| A weekly short survey sent out by SMS to the smartphone | Custom quantitative (ratings) regarding adoption and adherence to the interventions. | Adoption: yes/no Adherence to intervention principles on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 = not at all to 6 = to a very high degree. Delivery of minutes each day—open the box to write the number of minutes delivered. |

| Semi-structured post-intervention group interviews (present) | Interview questions (examples): Implementation: What did it take to implement this intervention? Adaptation: How has your practice changed throughout the eight weeks? | Interviews were recorded and transcribed. |

| Observations | Field observations of teachers delivering the interventions. | Jotted field notes |

| Intervention | Level of Strategy | Strategy | Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|

| Run, Jump & Fun | Staff delivery | 4 × 30 minutes weekly with MVPA intensity | Applying seven principles of RJF intervention |

| Staff capacity (understanding) | Two courses (6 and 3 hours) | Introduction to principles, practice tools and implementation Planning of activities Tailored feedback | |

| Staff capacity (understanding) | Teaching materials | Posters, booklets, lesson plans and links with specific activities and videos | |

| System climate (school support) | Run, Jump & Fun establishing process. | 3 Meetings before and one during the intervention. Meeting guidance provided by ACTIVE SCHOOL | |

| System climate (school support) | Team meetings | For teachers and school principals. Meeting guidance provided by ACTIVE SCHOOL. | |

| Move & Lean | Staff delivery | 2 × 30 minutes of ML Math weekly 2 × 30 minutes of ML Danish weekly | Applying five principles of ML intervention |

| Staff capacity (understanding) | Two courses (6 and 3 hours) | Introduction to principles, practice tools and implementation Planning of activities Tailored feedback | |

| Staff capacity (understanding) | Teaching materials | Posters, booklets, lesson plans and links with specific activities and videos | |

| System climate (school support) | Team meetings | For teachers and school principals. Meeting guidance provided by ACTIVE SCHOOL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sohl Jeppesen, L.; Sandfeld, J.; Smedegaard, S.; Nielsen, G.; Mandelid, M.B.; Norup, M.; Wienecke, J.; Bugge, A. Implementation Outcomes and Recommendations of Two Physical Activity Interventions: Results from the Danish ACTIVE SCHOOL Feasibility Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010067

Sohl Jeppesen L, Sandfeld J, Smedegaard S, Nielsen G, Mandelid MB, Norup M, Wienecke J, Bugge A. Implementation Outcomes and Recommendations of Two Physical Activity Interventions: Results from the Danish ACTIVE SCHOOL Feasibility Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(1):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010067

Chicago/Turabian StyleSohl Jeppesen, Lise, Jesper Sandfeld, Søren Smedegaard, Glen Nielsen, Mathias Brekke Mandelid, Malene Norup, Jacob Wienecke, and Anna Bugge. 2025. "Implementation Outcomes and Recommendations of Two Physical Activity Interventions: Results from the Danish ACTIVE SCHOOL Feasibility Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 1: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010067

APA StyleSohl Jeppesen, L., Sandfeld, J., Smedegaard, S., Nielsen, G., Mandelid, M. B., Norup, M., Wienecke, J., & Bugge, A. (2025). Implementation Outcomes and Recommendations of Two Physical Activity Interventions: Results from the Danish ACTIVE SCHOOL Feasibility Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22010067