Understanding the Wellbeing Needs of First Nations Children in Out-of-Home Care in Australia: A Comprehensive Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Team

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

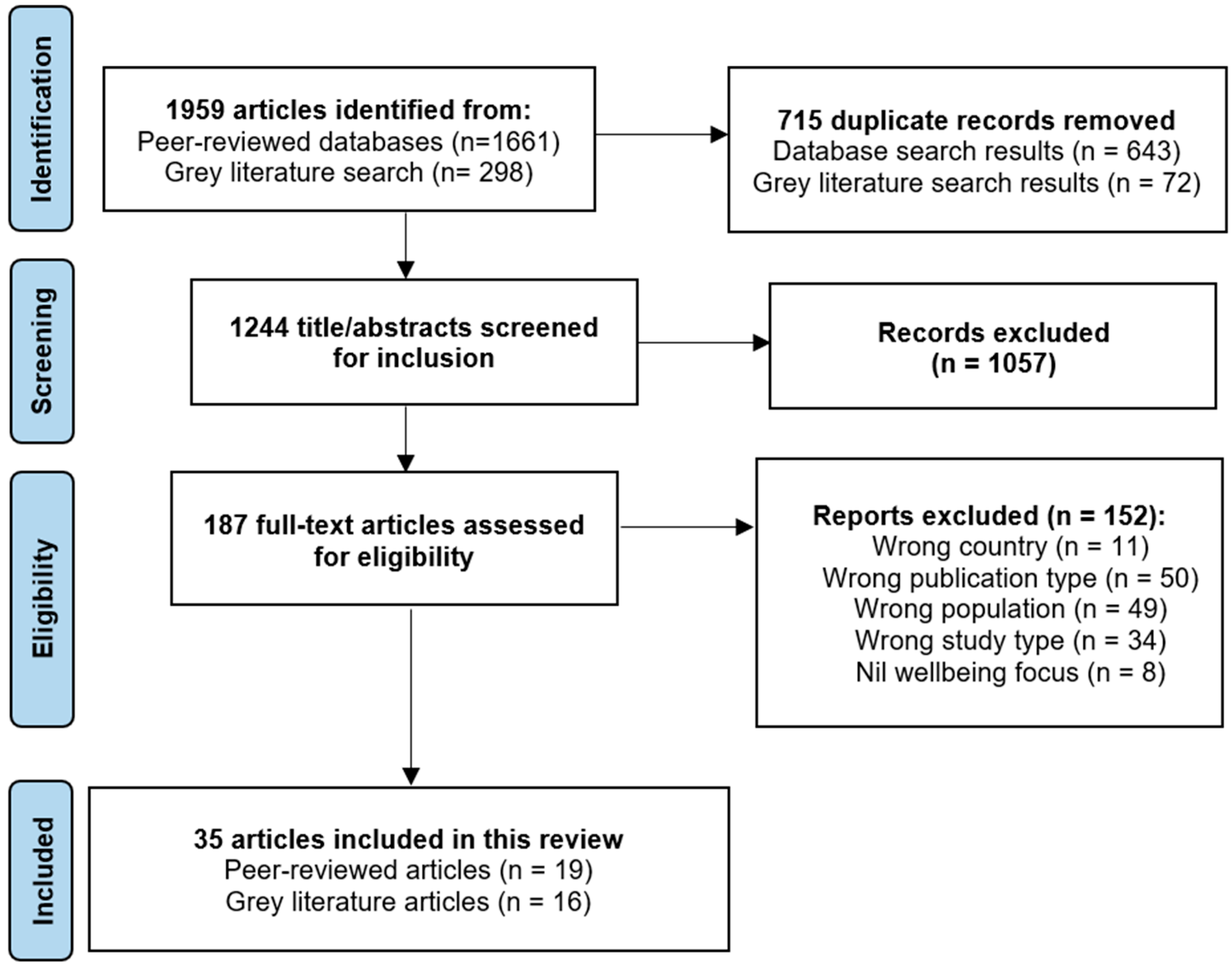

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Paper Characteristics

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.3. Being Seen, Being Heard

3.3.1. Having Autonomy and Agency

Talk to the actual kids, they’ll be very honest about their placement they don’t hide nothing get new workers to build trust with them kids and they will just spill their guts really.(Sally, worker) [47]

I think it’s like ya get dropped out of the loop… But basically we all are feeling so left out of things, these things are happening, we might be young but some sort of explanation would just go a mile…(Caroline, post-care, 19, Aboriginal) [33]

In some cases, while FACS [Family and Community Services] involved the children in some decision-making, the reviewer identified that this consultation was not ongoing. Children have the right to be involved in decisions that affect them and impact their lives, and this failure to consult on an ongoing basis was identified as disempowering practice.(Case file reviewer) [38]

3.3.2. Being Treated Like a Child, Not a Number

It is so important to know the kids you are working with; each person is an individual. It is just bloody critical that these kids are seen, known and not just a number. This is the work I am so passionate about.(Child Protection staff member) [33]

They should listen to young people. Hear what they have to say to ask them what they think and if they are safe.(15-year-old First Nations girl in care) [52]

I was lucky ’cos my grandparents made me feel like I was part of the family. I was never, ever introduced as their foster child and that made me feel loved and appreciated. I would encourage foster carers to try and do that, that was the most important thing.(Caden, post-care, 19, Aboriginal) [33]

My foster carers…were Aboriginal. They taught me stuff about culture. They helped me keep in contact with family. I stuck with one for most of it… They listened to me… [Carer] was really understanding. He understood why I was misbehaving sometimes.(Phoebe, returned home, 16, Aboriginal) [33]

3.4. A Sense of Stability

3.4.1. Experiencing Placement Stability

Stability for Aboriginal people is grounded in their sense of identity in connection to family, kin, culture and country. In our view, permanent care/adoption potentially places an emphasis on achieving stability of living arrangements and a secure legal status potentially at the cost of the child’s identity and enduring relationships with their extended family and connection with community and culture.(Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency) [34]

3.4.2. Receiving Support in School

I always tell them [First Nations children in OOHC engaging in education] who I am and what I’m there to do. And then I ask them if they want to. Because I make sure that they are involved in the decision making of being involved. And I did have two kids go, ‘No. I’m not quite sure’. But then in the end, became involved. I think part of it is also listening to them about what they want.(Education engagement intervention program teacher/mentor) [62]

3.4.3. Being on a Pathway to Culturally Appropriate Permanency

SNAICC submitted that permanency for Aboriginal children was ‘tied to existing identity, kinship relationships, and connections to culture and country’, and that it was important not to permanently deprive children of these connections through the application of ‘inflexible permanency planning measures.(SNAICC) [38]

3.5. Holistic Health Support

3.5.1. Fulfilment of Basic Needs

Most of us kids, the reason why we are in care is because our families are not reliable. You know, money problems, food, clothes, safety problems… The whole reason why they took us off our family was because we feel unsafe, we don’t feel much protected, there’s no food, and we’re not getting clothes… we’re not getting anything. But what’s the point of that if they do exactly the same in all these houses. It’s not better either way: living with our family, living with DCP [Department for Child Protection], government homes… or living on the streets… it’s not good anywhere.(17-year-old Aboriginal male, residential care) [35]

3.5.2. Receiving Care for Health and Physical Wellbeing

I think another trend that we found is that we’ve got a number of young people who have gone through the care system to be diagnosed as foetal alcohol syndrome at 18. And they’ve already been in and out of detention and they’ve got involvement with the justice system, and now they’re 18, it’s the adult justice system, which is a real concern. One young fella in particular I’m thinking of, was actually in residential care and wasn’t diagnosed until he was 18.(Western Australian NGO) [49]

3.5.3. Provision of Trauma-Informed Care

FACS fails to acknowledge that the removal of Aboriginal children from their families often exposes them to danger and ‘immense trauma’, as opposed to ‘protection’, (National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples) and that FACS intervention in and of itself is an extremely arduous, traumatic process that is actively harmful to all involved, particularly children.(Grandmothers Against Removals New South Wales) [38]

A lot of kids have had severe trauma, been too exposed to a lot of negative experiences, and you can see it, like behavioural change. A lot of the kids are getting suspended all the time, they’re acting out, they just show all the different traits, like physically, emotionally. You can see, spiritually, that they’re impacted too, on a lot of different levels. Their confidence is low, self-esteem, yeah, just a lot of different things.(NSW ACCO) [49]

While in placement, with the support of a strong and therapeutic care team, an appropriate cultural support plan and a KESO [Koorie Engagement Support Officer], Molly’s [Aboriginal girl in OOHC] behaviours have settled. Molly has told child protection she feels safe and secure with her carers.(caseworker/reviewer) [42]

3.6. Social and Cultural Connections

3.6.1. Fostering Interconnected Relationships

The major difficulty in the urban setting was appropriately placing children culturally, working out where they belonged.(ACCO staff) [65]

3.6.2. Maintaining Cultural Knowledge and Identity

Being Aboriginal is the proudest thing in my life, to know that that’s my people. It made me so proud to see what we’ve actually done and how far we’ve come to this day. It taught me that no matter what, I can still get up and do what I want.(Aboriginal child in OOHC) [36]

They [First Nations children and youth upon entering cultural camps] didn’t know their connections to communities, didn’t know about the language, didn’t eat Aboriginal food, they knew nothing at all [of their culture].(Aboriginal education officer) [36]

3.6.3. Feeling Connected to Community and Country

Aboriginal children coming into care should be placed in their own country. Just because they’re Aboriginal, isn’t good enough. You need to be placed with people who know your identity.(Non-First Nations carer) [54]

Participants identified a strong cultural identity and effective connection with community as a powerful source of resilience for Indigenous young people during and post transition from care.(ACCO and Government OOHC workers) [50]

3.6.4. Continued Links to Family and Kin

Give Aboriginal kids back to their home, their family, after you’ve gone through and made sure everything is all safe and all good. If not the mother and father, then maybe the kid has sisters, aunties, or an Aboriginal carer is available.(Aboriginal caregiver) [36]

Living there [in kinship care] feels like a family.(Shane, kinship care, 15, Aboriginal) [33]

Well, the strength [of kinship care] is that children remain within their extended family, which supports our philosophy around self-determination, self-management. The family best knows the family circumstances.(Jenny, worker) [37]

His [First Nations, 8 year old boy in relative care] older siblings were scattered geographically but it was clear from his narrative that he wanted regular contact with his older siblings.(OOHC team leader and art therapist) [52]

If I need to talk to someone now, my brother would be the first person I would talk to.(Ellie, residential care, 16, Aboriginal) [33]

I had someone sit down with me and go through everything, my mob, my family. There is nothing else I need to know.(Female, First Nations, 17 years) [48]

I want to find out if I have a cultural support plan so I can get help finding more info about my culture and where my family was from.(Female, First Nations, 14 years) [48]

Few months ago I asked [Department of Health and Human Services, Victoria] if I could find my dad. Haven’t seen him since I was one. Part of my life I’ve never met, so not good. My dad is the only actual family I know.(Evan, foster care, 15, Aboriginal) [33]

3.6.5. Being Supported by Friends

Q: Who do you go to for support?My friends, but more like my best friends. I’ve known them since I was like three and we’ve always stayed in contact and if I have a problem on my mind, I can always just go to his house.(Ethan, kinship care, 15, Aboriginal) [33]

3.7. Culturally Safe OOHC Providers

3.7.1. Supported by OOHC Organizations Trusted by First Nations Peoples

We understand where people [Aboriginal families] come from you can’t just have a mainstream organisation culturally competent, its philosophy is driven by white people, how they were raised, how they understand programs and services.(ACCO staff) [47]

3.7.2. Provision of Support Services Grounded in Culturally Safe Approaches

Aboriginal community-controlled agencies are best placed to support Aboriginal children and young people in OOHC, including maintaining their connection to family, community, culture and Country that is central to identity development and wellbeing.(New South Wales Council of Social Service) [38]

3.8. Preparedness for Transitioning Out of Care

3.8.1. Given Adequate Opportunities for Reunification with Family

He [14-year-old Aboriginal/South Sea Islander boy in OOHC] showed little attachment to the carer in that he talked of running away and not needing anyone.(OOHC team leader and art therapist) [52]

We’ve got lots of kids walking from care and leaving at 15. And particularly going back to Country or trying to find Country.(New South Wales NGO) [49]

3.8.2. Provided with Life Skills for after Care

We know there are 16, 17, 18-year-olds out there that can’t even boil water, you know, yet they want to fall pregnant; so if you can get it in there early enough to get these old people to teach these children survival skills, and not just Indigenous (skills), but also how to cook a meal and sew a button on.(Carer) [39]

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Commonwealth of Australia. An Outline of National Standards for Out-of-Home Care; Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, National Framework Implementation Working Group: Canberra, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Child protection Australia 2020–2021. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child-protection/child-protection-australia-2020-21 (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Liddle, C.; Gray, P.; Burton, J.; Prideaux, C.; Solomon, N.; Cackett, J.; Jones, M.; Bhathal, A.; Corrales, T.; Parolini, A.; et al. The Family Matters Report 2021; SNAICC: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Productivity Commission. Closing the Gap Annual Data Compilation Report July 2023; Productivity Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Productivity Commission. Report on Government Services Part F, Section 16: Child Protection Services 2024; Australian Government, Productivity Commission: Melbourne, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander First Action Plan 2023–2026 under Safe and Supported: The National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2021–2031; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kickett, G.; Stubley, K. Moving to Child Safety and Family and Community Wellbeing; Centre for Social Impact (University of Western Australia) Department of Communities Western Australia: Nedlands, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Angell, B.; Muhunthan, J.; Eades, A.-M.; Cunningham, J.; Garvey, G.; Cass, A.; Howard, K.; Ratcliffe, J.; Eades, S.; Jan, S. The health-related quality of life of Indigenous populations: A global systematic review. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 2161–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T.L.; Anderson, K.; Garvey, G.; Cunningham, J.; Ratcliffe, J.; Tong, A.; Whop, L.J.; Cass, A.; Dickson, M.; Howard, K. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s domains of wellbeing: A comprehensive literature review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 233, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvey, G.; Anderson, K.; Gall, A.; Butler, T.L.; Cunningham, J.; Whop, L.J.; Dickson, M.; Ratcliffe, J.; Cass, A.; Tong, A.; et al. What Matters 2 Adults (WM2Adults): Understanding the Foundations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, G.; Anderson, K.; Gall, A.; Butler, T.L.; Whop, L.J.; Arley, B.; Cunningham, J.; Dickson, M.; Cass, A.; Ratcliffe, J.; et al. The Fabric of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Wellbeing: A Conceptual Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.; Elder-Robinson, E.; Gall, A.; Ngampromwongse, K.; Connolly, M.; Letendre, A.; Willing, E.; Akuhata-Huntington, Z.; Howard, K.; Dickson, M.; et al. Aspects of Wellbeing for Indigenous Youth in CANZUS Countries: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, A.; Anderson, K.; Howard, K.; Diaz, A.; King, A.; Willing, E.; Connolly, M.; Lindsay, D.; Garvey, G. Wellbeing of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, Aotearoa (New Zealand) and the United States: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudgeon, P.; Bray, A.; Smallwood, G.; Walker, R.; Dalton, T. Wellbeing and Healing through Connection and Culture; Lifeline Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (General Assembly). Convention on the Rights of the Child; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (General Assembly). Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jackomos, A. Being strong in aboriginal identity and culture protects young people leaving care. Parity 2016, 29, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, J.; Young, J.; Jayakody, N.; Ruggiero, E.; Thwaites, R. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle: A Guide to Support Implementation; SNAICC: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gatwiri, K.; McPherson, L.; Parmenter, N.; Cameron, N.; Rotumah, D. Indigenous Children and Young People in Residential Care: A Systematic Scoping Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2019, 22, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, N.; Bromfield, L. Cultural Considerations in Out-of-Home Care; Australian Institute of Family Studies: Melbourne, Australia, 2007; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharabaghi, K.; Anderson-Nathe, B. Strength-based research in a deficits-oriented context. Child Youth Serv. 2017, 38, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsman, H.; Vinnerljung, B. Interventions aiming to improve school achievements of children in out-of-home care: A scoping review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kääriälä, A.; Hiilamo, H. Children in out-of-home care as young adults: A systematic review of outcomes in the Nordic countries. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 79, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, V.; Caldwell, J.; Paul, L.; Fumaneri, P.R. A Review of Literature on the Involvement of Children from Indigenous Communities in Anglo Child Welfare Systems: 1973–2018. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2021, 12, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EndNote Team. EndNote, EndNote 20; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Veritas Health Information. Covidence Systematic Review Software. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel. Available online: https://office.microsoft.com/excel (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Lumivero. NVivo (Version 13) [Computer Software]. Available online: https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/ (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport. Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231205789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission for Children and Young People. ‘In Our Own Words’: Systemic Inquiry into the Lived Experience of Children and Young People in the Victorian Out-of-Home Care System; Commission for Children and Young People: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull-Roberts, V.; Salter, M.; Newton, B.J. Trauma then and now: Implications of adoption reform for first nations children. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2021, 27, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commissioner for Children and Young People WA. Speaking out about Raising Concerns in Care; Commissioner for Children and Young People WA: Perth, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- AbSec—NSW Child Family and Community Peak Aboriginal Corporation. Hearing the Voices of Aboriginal People in Child Welfare; Absec—NSW Child, Family and Community Peak Aboriginal Corporation: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kiraly, M.; James, J.; Humphreys, C. “It”s a family responsibility’: Family and cultural connection for Aboriginal children in kinship care. Child. Aust. 2014, 40, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M. Family Is Culture: Independent Review into Aboriginal Out-of-Home Care in NSW; New South Wales Department of Family and Community Services: Sydney, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, A.; Reck, L.; Walker, M. Defining well-being for Indigenous children in care. Child. Aust. 2007, 32, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advocate for Children Young People (NSW). The Voices of Children and Young People in Out-of-Home Care 2021; Advocate for Children and Young People (NSW): Sydney, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bamblett, M.; Frederico, M.; Harrison, J.; Jackson, A.; Lewis, P. ’Not One Size Fits All’ Understanding the Social & Emotional Wellbeing of Aboriginal Children; La Trobe University: Bundoora, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Commission for Children and Young People. ‘Always Was Always Will Be Koori Children’: Systemic Inquiry into Services Provided to Aboriginal Children and Young People in Out-of-Home Care in Victoria; Commission for Children and Young People: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hermeston, W.; McDougall, J.; Burton, J.; Smith, F.; Sydenham, E. Achieving Stability for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children in Out-of-Home Care; SNAICC: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, D.J.; Bromfield, L.M.; Higgins, J.R.; Richardson, N. Protecting Indigenous children: Views of carers and young people on “out-of-home care”. Fam. Matters 2006, 75, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kiraly, M.; Humphreys, C. ‘It Is the Story of All Us’. Learning from Aboriginal Communities about Supporting Family Connection; State of Victoria: Melbourne, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, N.; Weston, R.; Burton, J.; Young, J.; Jayakody, N.; Mastroianni, A.; Tan, W.W.; Parolini, A.; Shlonsky, A.; Tilbury, C. The Family Matters Report 2019; SNAICC: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Libesman, T. Cultural Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children in Out of Home Care; SNAICC: Melbourne, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McDowall, J.J. Out-of-Home Care in Australia: Children and Young People’s Views after Five Years of National Standards; CREATE Foundation: Sydney, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, P.; Standfield, R.; Saunders, B.; McCurdy, S.; Walsh, J.; Turnbull, L. Indigenous youth transitioning from out-of-home care in Australia: A study of key challenges and effective practice responses. J. Child. Serv. 2022, 17, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, P.; Standfield, R.; Saunders, B.; McCurdy, S.; Walsh, J.; Turnbull, L. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (Indigenous) young people leaving out-of-home care in Australia: A national scoping study. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 121, 105848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.; Bennett, B.; McArthur, M. They’ve Gotta Listen: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Young People in Out of Home Care; 192123914X; Australian Catholic University: Dickson, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, M. Broken circles to a different identity: An exploration of identity for children in out-of-home care in Queensland, Australia. Child. Fam. Soc. Work. 2009, 14, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, N. Kinship Care in Australia. Child Abus. Rev. 2004, 13, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, D.; Bromfield, L.; Richardson, N.; National Child Protection Clearinghouse. Enhancing Out-of-Home Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Young People; Australian Institute of Family Studies: Melbourne, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle, C.; Gray, P.; Burton, J.; Taylor, M.; Young, G.; Kumar, R.; Turner, L.; Hutchins, L.; French, B.; Jones, L.A.; et al. The Family Matters Report 2023; SNAICC: Melbourne, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Black, C.; Frederico, M.; Bamblett, M. ‘Healing through culture’: Aboriginal young people’s experiences of social and emotional wellbeing impacts of cultural strengthening programs. Child Abus. Negl. 2023, 148, 106206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, S.; Blair, S.; Toombs, M.; Brolan, C.E. Indigenous services leading the way for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care. Soc. Work Educ. 2024, 43, 913–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jau, J.; Mendes, P.; Chavulak, J.; Martin, R. The Housing Pathways and Experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Youth as They Transition from out of Home Care in Victoria and Western Australia. Int. J. Child Maltreatment 2022, 5, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakouer, J. Journeys of culturally connecting: Aboriginal young people’s experiences of cultural connection in and beyond out-of-home care. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2023, 28, 822–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddle, C.; Gray, P.; Burton, J.; Kumar, R.; Tunny, T.; Prideaux, C.; Armstrong, E.; McCracken, A.; French, B.; Attenborough, I.; et al. The Family Matters Report 2022; SNAICC: Melbourne, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, B.J.; Katz, I.; Gray, P.; Frost, S.; Gelaw, Y.; Hu, N.; Lingam, R.; Stephensen, J. Restoration from out-of-home care for Aboriginal children: Evidence from the pathways of care longitudinal study and experiences of parents and children. Child Abus. Negl. 2023, 149, 106058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, S.; Dunk-West, P.; Otarra, C.; Taylor, R.; Moss, M. Exploring strategies for re-engaging children and young people in learning while living in out-of-home care in the Northern Territory, Australia. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2023, 28, 1022–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.; Healy, K.; Lynch, D.; Featherstone, G. Stability in statutory kinship care: A grounded theory study of placement stability in Australia. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2024, 156, 107289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.C.; Collings, S. Conceptual meanings of permanency: Photovoice with care-experienced youth. J. Youth Stud. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, S.; Ruston, S.; Irwin, S.; Tran, P.; Hotton, P.; Thorne, S. Taking culture seriously: Can we improve the developmental health and well-being of Australian aboriginal children in out-of-home care? Child Care Health Dev. 2017, 43, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kor, K.; Park, J.; Dear, R.; Fabrianesi, B. Responding to children’s ambiguous loss in out-of-home care: The HEAR practice model. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2024, 29, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamblett, M.; Lewis, P. Detoxifying the Child and Family Welfare System for Australian Indigenous Peoples: Self-determination, Rights and Culture as the Critical Tools. First Peoples Child Fam. Rev. 2007, 3, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassall, A.; Olsen, A.; Bourke, S.; Pasalich, D.S. How do kinship and foster caregivers differ in their conceptualization of family connectedness? Child Abus. Negl. 2023, 145, 106391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, C.; Gray, P.; Bennet, D.; Elliott, A.; Jackomos, M.; Krakouer, J.; Marriott, R.; O’Dea, B.; Andrews, J.; Andrews, S.; et al. Supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Families to Stay Together from the Start (SAFeST Start): Urgent call to action to address crisis in infant removals. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2022, 57, 252–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, E.; Lee, J.-S.; McNamara, P. Understanding the Experience and Outcomes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children in Out-of-Home Care during the Twentieth Century; University of New South Wales: Kensington, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, P. “The most significant child welfare reform in a generation”: An examination of the strategies used by the Home Stretch campaign. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2024, 59, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subject Term | Search Terms | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | OOHC [22,23,24] | “out of home care” OR “out-of-home care” OR OOHC OR “out of home placement” OR “out-of-home placement” OR “residential care” OR “state care” OR “public care” OR “kinship care” OR “in care” OR “foster care” OR “foster family care” OR “foster home care” OR “foster child*” OR “guardian*” (TI/AB) |

| 2 | Wellbeing [9,13] | wellbeing OR well-being OR SEWB OR “quality of life” OR HR-QOL OR HRQOL OR QOL OR wellness OR “life quality” OR “health related quality of life” OR “health-related quality of life” OR “cultur*” (TI/AB) |

| 3 | First Nations Australians [9] | Aborigin* OR Indigenous OR “Torres Strait” OR “First Nation*” OR “First Australia*” (TI/AB) |

| 4 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 |

| Wellbeing Needs (Themes) and Aspects of Care (Subthemes) | Quotes |

|---|---|

| 3.3. Being seen, being heard 3.3.1 Having autonomy and agency 3.3.2 Being treated like a child, not a number | I think it’s like ya get dropped out of the loop… But basically we all are feeling so left out of things, these things are happening, we might be young but some sort of explanation would just go a mile… (Caroline, post-care, 19, Aboriginal) [33] |

| 3.4. A sense of stability 3.4.1. Experiencing placement stability 3.4.2. Receiving support in school 3.4.3. Being on a pathway to culturally appropriate permanency | Stability for Aboriginal people is grounded in their sense of identity in connection to family, kin, culture and country. In our view, permanent care/adoption potentially places an emphasis on achieving stability of living arrangements and a secure legal status potentially at the cost of the child’s identity and enduring relationships with their extended family and connection with community and culture. (Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency) [34] |

| 3.5. Holistic health support 3.5.1. Fulfilment of basic needs 3.5.2. Receiving care for health and physical wellbeing 3.5.3. Provision of trauma-informed care | Most of us kids, the reason why we are in care is because our families are not reliable. You know, money problems, food, clothes, safety problems… The whole reason why they took us off our family was because we feel unsafe, we don’t feel much protected, there’s no food, and we’re not getting clothes… we’re not getting anything. But what’s the point of that if they do exactly the same in all these houses. It’s not better either way: living with our family, living with DCP [Department for Child Protection], government homes… or living on the streets… it’s not good anywhere. (17-year-old Aboriginal male, residential care) [35] |

| 3.6. Social and cultural connections 3.6.1. Fostering interconnected relationships 3.6.2. Maintaining cultural knowledge and identity 3.6.3. Feeling connected to community and Country 3.6.4. Continued links to family and kin 3.6.5. Being supported by friends | Being Aboriginal is the proudest thing in my life, to know that that’s my people. It made me so proud to see what we’ve actually done and how far we’ve come to this day. It taught me that no matter what, I can still get up and do what I want. (Aboriginal child in OOHC) [36] Well, the strength [of kinship care] is that children remain within their extended family, which supports our philosophy around self-determination, self-management. The family best knows the family circumstances. (Jenny, worker) [37] |

| 3.7. Culturally safe OOHC providers 3.7.1. Supported by OOHC organizations trusted by First Nations peoples 3.7.2. Provision of support services grounded in culturally safe approaches | Aboriginal community-controlled agencies are best placed to support Aboriginal children and young people in OOHC, including maintaining their connection to family, community, culture and Country that is central to identity development and wellbeing. (New South Wales Council of Social Service) [38] |

| 3.8. Preparedness for transitioning out of care 3.8.1. Given adequate opportunities for reunification with family 3.8.2. Provided with life skills for after care | We know there are 16, 17, 18-year-olds out there that can’t even boil water, you know, yet they want to fall pregnant; so if you can get it in there early enough to get these old people to teach these children survival skills, and not just Indigenous (skills), but also how to cook a meal and sew a button on. (Carer) [39] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garvey, D.; Carter, K.; Anderson, K.; Gall, A.; Howard, K.; Venables, J.; Healy, K.; Bill, L.; Letendre, A.; Dickson, M.; et al. Understanding the Wellbeing Needs of First Nations Children in Out-of-Home Care in Australia: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091208

Garvey D, Carter K, Anderson K, Gall A, Howard K, Venables J, Healy K, Bill L, Letendre A, Dickson M, et al. Understanding the Wellbeing Needs of First Nations Children in Out-of-Home Care in Australia: A Comprehensive Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(9):1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091208

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarvey, Darren, Ken Carter, Kate Anderson, Alana Gall, Kirsten Howard, Jemma Venables, Karen Healy, Lea Bill, Angeline Letendre, Michelle Dickson, and et al. 2024. "Understanding the Wellbeing Needs of First Nations Children in Out-of-Home Care in Australia: A Comprehensive Literature Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 9: 1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091208

APA StyleGarvey, D., Carter, K., Anderson, K., Gall, A., Howard, K., Venables, J., Healy, K., Bill, L., Letendre, A., Dickson, M., & Garvey, G. (2024). Understanding the Wellbeing Needs of First Nations Children in Out-of-Home Care in Australia: A Comprehensive Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(9), 1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091208