“It Empowers You to Empower Them”: Health Professional Perspectives of Care for Hyperglycaemia in Pregnancy Following a Multi-Component Health Systems Intervention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Health Systems Intervention Design

- Increasing workforce capacity, skills and knowledge, and improving the health literacy of women;

- Improving access to healthcare through culturally and clinically appropriate pathways;

- Improving information management and communication;

- Enhancing policies and guidelines;

- Embedding clinical registers for women with hyperglycaemia in pregnancy—the NT and FNQ Diabetes in Pregnancy (DIP) Clinical Registers—within models of care.

2.3. Evaluation Methods

2.3.1. Interviews

2.3.2. Surveys

2.3.3. Ethics and Governance

3. Findings

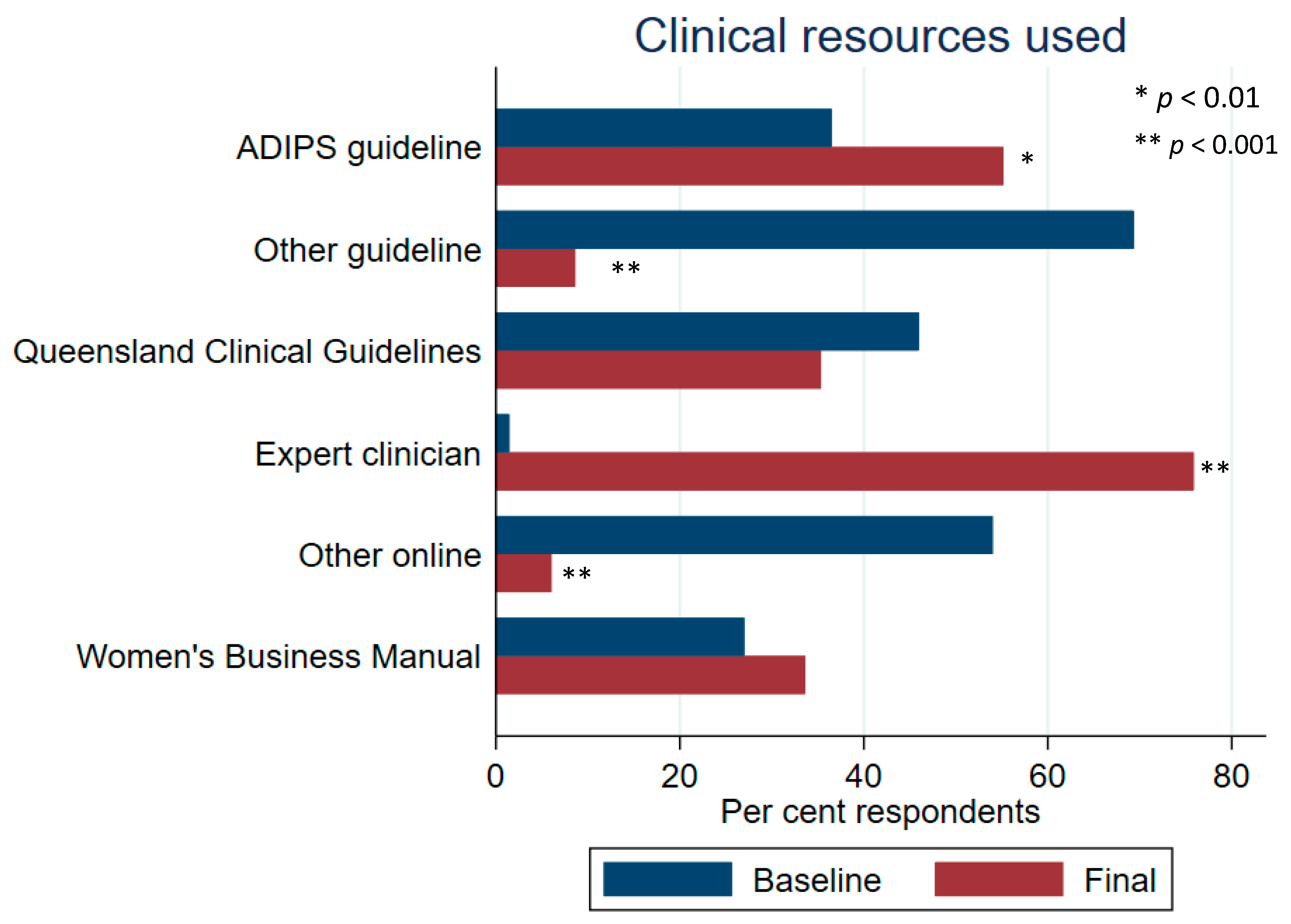

3.1. Health Professional Clinical Practice

I think certainly some clinicians realise that as a midwife we’re a generalist, and that you really can’t care for women who have diabetes in pregnancy without specialised support services. (Midwife, primary care, FNQ)

So we’ve been seeing people earlier I think... I think raising awareness of that early screening has potentially made a change. (Medical practitioner, hospital, FNQ)

And usually it’s [referral] been quite close to diagnosis … whereas previously we might have picked them up quite late and not had the opportunity to see them … we’ve sometimes been able to have a bit more ongoing input throughout their pregnancy rather than just that little tail end. (Dietitian, primary care, Central Australia)

So also just that, like one of the things that the project probably reminded me of more is also the follow-up. Like I’ve known the follow-up had to happen, but just coming up with different ways within an electronic system to try and make it happen. (Diabetes educator, primary care, FNQ)

So I think our postpartum screening might have improved, and I think a lot of that is around communication and reminders. (Midwife, hospital, FNQ)

3.2. Health Systems

We have regular conferences with the obs and gynae … I think there’s more of a team, we’re all on the same team, and you don’t have the ivory towers that you had before. (Diabetes educator, primary care, Top End)

They [primary care clinicians] know the people [at referral centre] and they know how to get in touch with them so that’s made a big difference. (Midwife, hospital, Central Australia)

The capacity to network, being part of that wider reference group. Especially when you’re working remote, you don’t get to network a lot with people across services. (Medical practitioner, primary care and hospital, Central Australia)

We also give the ladies a choice where they’d like to go. So at the start, when I first started… it seemed like they were wanting all the ladies to go to [hospital] clinic. But a lot of the ladies were leaving. It wasn’t, didn’t feel culturally appropriate. So now we say where would you like to go? You can come to [primary care clinic] or you can go to [hospital] or you can do a bit of both. (Diabetes educator, primary care, Central Australia)

The opportunities have opened up for us to be able to communicate in a better way, so that we all can work collaboratively in a group instead of in our own silos. (Diabetes educator, primary care, Central Australia)

I’ve had a lot of feedback from our rural sites that communication is so much better and the outcomes are much better and women are happier and things like that. (Midwife, hospital, FNQ)

Sometimes you get feedback from the antenatal clinic when they go down for appointments and stuff… sometimes it’s good, sometimes it’s completely absent, sometimes it’s timely and sometimes it’s three or four weeks later when you’ve asked for it …that’s a real struggle. (Midwife, primary care, FNQ)

The Partnership’s provided the foundation, I suppose, so the foundation for me to be able to say yep, this is why we’re doing this [laughs] and this is why we’re investing in a clinic being set up this way. (Medical practitioner, hospital, Central Australia)

What reports we had coming off the clinical register were showing that our breastfeeding rates [for women with type 2 diabetes] on discharge were reasonably low and that within 12 months were low as well and there’s been some discussions around that... And so it’s been a discussion about … what we’re recommending, but these are some of the reasons that women aren’t breastfeeding and those reasons need to be heard. (Implementer and Diabetes educator, hospital, Top End)

… maybe that approach can inform practice to say, you know, we need extra services for our high-risk Aboriginal population. (Diabetes educator, primary care, Central Australia)

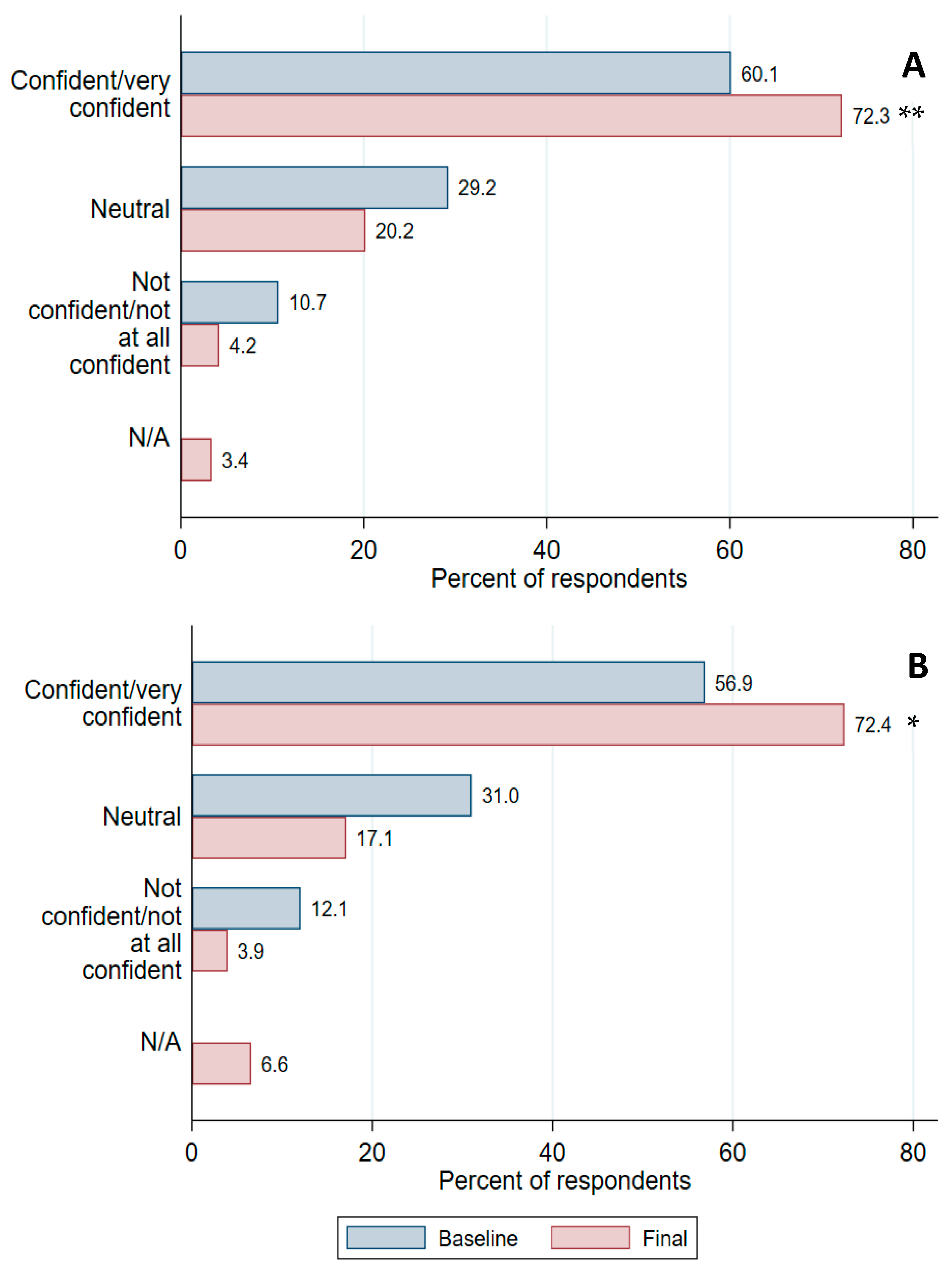

3.3. Health Professional Confidence and Knowledge

Definitely, they’re [clinicians] talking to them [women] because they’ve got more information on that understanding about the diabetes in pregnancy and it’s like anything, you have the information, it empowers you to empower them or to empower anybody. (Diabetes educator, primary care, Central Australia)

It did raise the profile of diabetes in pregnancy and the importance of it and how, actually, it’s everyone’s business. (Midwife, primary care, Central Australia)

With the information that we deliver with some of the brochures, women are wanting more knowledge, they are seeking more knowledge. (Midwife, primary care, Central Australia)

3.4. Opportunities for Further Improvements

It’s very obvious to me down on the ground that there’s a whole heap of cross-cultural communication stuff that has to happen better, and there’s totally different models of disease and illness that we haven’t really put diabetes into a good conversation with. (Medical officer, primary care and hospital, Central Australia)

I think some clinicians believe in the autonomy of the woman, and not that I don’t believe in the autonomy of the woman, I do believe in the autonomy of the woman, but I think sometimes the autonomy of the woman can only be created if she receives enough education to truly be able to have informed autonomy. (Midwife, primary care, FNQ)

The bottom line is that most of our clients already think we share records, they can’t believe that you don’t understand what happened in at [referral hospital] when they came out. (Diabetes educator, primary care, FNQ)

In addition to food security issues, which are still ongoing, housing problems, which are still ongoing, domestic abuse, and other stuff. All of those play an important part into whether a woman is able to engage in the services. I think diabetes management would again be reflective of general socioeconomic progress in them, as they advance in that field, I think diabetes management will also become better. (Medical officer, hospital, Top End)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Agarwal, S.; Wade, A.N.; Mbanya, J.C.; Yajnik, C.; Thomas, N.; Egede, L.E.; Campbell, J.; Walker, R.J.; Maple-Brown, L.; Graham, S. The role of structural racism and geographical inequity in diabetes outcomes. Lancet 2023, 402, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.B.; Tompkins, J.W.; TeHiwi, B. Call to action: A new path for improving diabetes care for Indigenous peoples, a global review. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 123, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarkson, C.; Jacobs, Z.; Marwick, B.; Fullagar, R.; Wallis, L.; Smith, M.; Roberts, R.G.; Hayes, E.; Lowe, K.; Carah, X.; et al. Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago. Nature 2017, 547, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voaklander, B.; Rowe, S.; Sanni, O.; Campbell, S.; Eurich, D.; Ospina, M.B. Prevalence of diabetes in pregnancy among Indigenous women in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the USA: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e681–e698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hare, M.J.L.; Barzi, F.; Boyle, J.A.; Guthridge, S.; Dyck, R.F.; Barr, E.L.M.; Singh, G.; Falhammar, H.; Webster, V.; Shaw, J.E.; et al. Diabetes during pregnancy and birthweight trends among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory of Australia over 30 years. Lancet Reg. Health-West. Pac. 2020, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1991–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, H.R.; Howgate, C.; O’Keefe, J.; Myers, J.; Morgan, M.; Coleman, M.A.; Jolly, M.; Valabhji, J.; Scott, E.M.; Knighton, P.; et al. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: A 5-year national population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vounzoulaki, E.; Khunti, K.; Abner, S.C.; Tan, B.K.; Davies, M.J.; Gillies, C.L. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020, 369, m1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabelea, D. The predisposition to obesity and diabetes in offspring of diabetic mothers. Diabetes Care 2007, 30 (Suppl. S2), S169–S174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, D.; Desoye, G.; Dunne, F.; Simeoni, U.; Visser, G.H.A.; Kapur, A.; Hod, M. FIGO analysis of research priorities in hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 145, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, L.A.; Avalos, G.; Kirwan, B.; Carmody, L.; Dunne, F. ATLANTIC DIP: Closing the loop: A change in clinical practice can improve outcomes for women with pregestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1669–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarrington, C.; Zera, C. Health systems approaches to diabetes screening and prevention in women with a history of gestational diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2015, 15, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamel, M.S.; Werner, E.F. Interventions to improve rate of diabetes testing postpartum in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2017, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkham, R.; Boyle, J.A.; Whitbread, C.; Dowden, M.; Connors, C.; Corpus, S.; McCarthy, L.; Oats, J.; McIntyre, H.D.; on behalf of the NT Diabetes in Pregnancy Partnership. Health service changes to address diabetes in pregnancy in a complex setting: Perspectives of health professionals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkham, R.; King, S.; Graham, S.; Boyle, J.A.; Whitbread, C.; Skinner, T.; Rumbold, A.; Maple-Brown, L. ‘No sugar’, ‘no junk food’, ‘do more exercise’—Moving beyond simple messages to improve the health of Aboriginal women with Hyperglycaemia in Pregnancy in the Northern Territory—A phenomenological study. Women Birth 2020, 34, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkham, R.; Trap-Jensen, N.; Boyle, J.A.; Barzi, F.; Barr, E.L.M.; Whitbread, C.; Van Dokkum, P.; Kirkwood, M.; Connors, C.; Moore, E.; et al. Diabetes care in remote Australia: The antenatal, postpartum and inter-pregnancy period. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, A.; Kirkham, R.; Campbell, S.; Whitbread, C.; Barrett, J.; Connors, C.; Boyle, J.; Brown, A.; Mein, J.; Wenitong, M.; et al. Improving models of care for diabetes in pregnancy: Experience of current practice in Far North Queensland, Australia. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakerman, J.; Humphreys, J.; Russell, D.; Guthridge, S.; Bourke, L.; Dunbar, T.; Zhao, Y.; Ramjan, M.; Murakami-Gold, L.; Jones, M.P. Remote health workforce turnover and retention: What are the policy and practice priorities? Hum. Resour. Health 2019, 17, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns and Hinterland Hospital and Health Service. Annual Report 2017–2018; Queensland Government: Cairns, Australia, 2018.

- Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service. Annual Report 2017–2018; Queensland Government: Cairns, Australia, 2018.

- Department of Health—Strategy Policy and Planning Branch. Northern Territory Health Strategic Plan 2018–2022; Northern Territory Government: Darwin, Australia, 2018.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3101.0 Australian Demographic Statistics (Sep 2018); Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

- Cairns and Hinterland Hospital and Health Service. Casemix Report: Pregnancies Complicated by Diabetes; Cairns and Hinterland Hospital and Health Service: Cairns, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, S.; Li, L.; O’Neil, L.; Jennings, B. Mothers and Babies 2019—Northern Territory Midwives’ Collection; Department of Health: Darwin, Australia, 2022.

- MacKay, D.; Kirkham, R.; Freeman, N.; Murtha, K.; Van Dokkum, P.; Boyle, J.; Campbell, S.; Barzi, F.; Connors, C.; O’dea, K.; et al. Improving systems of care during and after a pregnancy complicated by hyperglycaemia: A protocol for a complex health systems intervention. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One21seventy National Centre for Quality Improvement in Indigenous Primary Health Care. Systems Assessment Tool. 2012. Available online: https://www.menzies.edu.au/page/Resources/Systems_Assessment_Tool_SAT/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Glasgow, R.E.; Vogt, T.M.; Boles, S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public. Health 1999, 89, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association Inc. Minymaku Kutju Tjukurpa—Women’s Business Manual, 6th ed.; RPHCM: Alice Springs, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Queensland Clinical Guidelines. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus; Department of Health: Darwin, Australia, 2015.

- Kildea, S.; Gao, Y.; Hickey, S.; Nelson, C.; Kruske, S.; Carson, A.; Currie, J.; Reynolds, M.; Wilson, K.; Watego, K.; et al. Effect of a Birthing on Country service redesign on maternal and neonatal health outcomes for First Nations Australians: A prospective, non-randomised, interventional trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e651–e659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerrigan, V.; McGrath, S.Y.; Majoni, S.W.; Walker, M.; Ahmat, M.; Lee, B.; Cass, A.; Hefler, M.; Ralph, A.P. “The talking bit of medicine, that’s the most important bit”: Doctors and Aboriginal interpreters collaborate to transform culturally competent hospital care. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, T.; MacKay, D.; Canuto, K.; Boyle, J.A.; D’Antoine, H.; Hampton, D.; Martin, K.; Phillips, J.; Bartlett, N.; Mcintyre, H.D.; et al. Supporting healthy lifestyles for First Nations women and communities through co-design: Lessons and early findings from remote Northern Australia. Front. Clin. Diabetes Healthc. 2024, 5, 1356060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, L.; Francis, J.; Islam, R.; O’Connor, D.; Patey, A.; Ivers, N.; Foy, R.; Duncan, E.M.; Colquhoun, H.; Grimshaw, J.M.; et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Forde, R.; Parsons, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Forbes, A. Interventions to increase the uptake of postpartum diabetes screening among women with previous gestational diabetes: A systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 101137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titmuss, A.; Davis, E.A.; O’Donnell, V.; Wenitong, M.; Maple-Brown, L.J.; Haynes, A.; Barr, E.L.M.; Boffa, J.; Brown, A.D.H.; Connors, C.; et al. Youth-onset type 2 diabetes among First Nations young people in northern Australia: A retrospective, cross-sectional study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkham, R.; Whitbread, C.; Connors, C.; Moore, E.; Boyle, J.A.; Richa, R.; Barzi, F.; Li, S.; Dowden, M.; Oats, J.; et al. Implementation of a diabetes in pregnancy clinical register in a complex setting: Findings from a process evaluation. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, D.I.R.; Versace, V.L.; Dunbar, J.A.; Scheil, W.; Janus, E.; Oats, J.J.N.; Skinner, T.; Shih, S.; O’reilly, S.; Sikaris, K.; et al. Results of the first recorded evaluation of a national gestational diabetes mellitus register: Challenges in screening, registration, and follow-up for diabetes risk. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, D.; Freeman, N.; Boyle, J.A.; Campbell, S.; McLean, A.; Peiris, D.; Corpus, S.; Connors, C.; Moore, E.; Wenitong, M.; et al. Improving systems of prenatal and postpartum care for hyperglycemia in pregnancy: A process evaluation. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 155, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Sands, D.Z.; Schneider, J.D. Quantifying the economic impact of communication inefficiencies in U.S. hospitals. J. Healthc. Manag. 2010, 55, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safran, D.G.; Miller, W.; Beckman, H. Organizational dimensions of relationship-centered care. Theory, evidence, and practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21 (Suppl. S1), S9–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remote Primary Healthcare Manuals. Women’s Business Manual, 7th ed.; Flinders University: Alice Sprints, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Edelson, P.K.; James, K.E.; Leong, A.; Arenas, J.; Cayford, M.; Callahan, M.J.; Bernstein, S.N.; Tangren, J.S.; Hivert, M.-F.; Higgins, J.M.; et al. Longitudinal Changes in the Relationship Between Hemoglobin A1c and Glucose Tolerance Across Pregnancy and Postpartum. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, e1999–e2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Profession | FNQ | CA | TE | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midwife | 6 | 6 | 3 | 15 |

| Medical practitioner | 2 | 4 | 5 | 11 |

| Diabetes educator | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 |

| Aboriginal health practitioner/Aboriginal health worker | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Dietitian | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Administrator | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Implementer | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| Total | 15 | 16 | 15 | 46 |

| Characteristic | Baseline N = 183 (%) | Post-Intervention N = 137 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Occupation | ||

| Nurse | 9 (4.9) | 5 (3.6) |

| Midwife | 57 (31.1) | 67 (48.9) |

| General Practitioner/GP Obstetrician | 38 (20.8) | 10 (7.3) |

| Medical Specialist | 9 (4.9) | 5 (3.6) |

| Medical Practitioner (other) | 3 (1.6) | 1 (0.7) |

| Diabetes Educator | 23 (12.6) | 25 (18.2) |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioner | 12 (6.6) | 3 (2.2) |

| Dietitian | 12 (6.6) | 11 (8.0) |

| Other * | 17 (9.3) | 10 (7.3) |

| Region | ||

| Northern Territory—Central Australia | 36 (19.8) | 40 (29.2) |

| Northern Territory—Top End | 45 (24.7) | 52 (38.0) |

| Far North Queensland | 101 (55.5) | 45 (32.8) |

| Main work setting | ||

| Regional/remote | 117 (67.6) | 73 (53.3) |

| Urban | 56 (32.4) | 64 (46.7) |

| Time in current position | ||

| <1 year | 33 (18.1) | 15 (11.0) |

| 1–5 years | 68 (37.4) | 54 (39.7) |

| 5–10 years | 32 (17.6) | 38 (27.9) |

| >10 years | 49 (26.9) | 29 (21.3) |

| Client ethnicity | ||

| Predominantly Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | 76 (42.7) | 72 (52.6) |

| Predominantly non-Indigenous | 12 (6.7) | 17 (12.4) |

| Mixed | 90 (50.6) | 48 (35.0) |

| Previous participation in Diabetes in Pregnancy survey | N/A | |

| Yes | 23 (16.8) | |

| No | 75 (54.7) | |

| Unsure | 39 (28.5) | |

| Primary place of work in primary health care | ||

| Yes | 143 (78.1) | 104 (76.5) |

| No | 40 (21.9) | 32 (23.5) |

| Baseline n (%) | Final n (%) | p Univariable Logistic Regression | p Multivariable Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical practice | ||||

| Practitioners screening for diabetes in early pregnancy # | ||||

| Yes | 95 (67.9) | 81 (81.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 a |

| No | 32 (22.9) | 1 (1.0) | ||

| Unsure | 13 (9.3) | 1 (1.0) | ||

| N/A—not viewed as part of practitioners’ role ^ | N/A | 17 (17.0) | ||

| Screening test most commonly used in first trimester # | ||||

| 75 g oral glucose tolerance test | 75 (50.0) | 56 (73.7) | 0.003 | 0.060 b |

| HbA1c | 33 (22.0) | 16 (21.1) | ||

| Random plasma glucose/blood glucose level | 22 (14.7) | 1 (1.3) | ||

| Fasting plasma glucose/blood glucose level | 3 (2.0) | 1 (1.3) | ||

| 50 g glucose challenge test | 3 (2.0) | 2 (2.6) | ||

| Unsure | 14 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Screening test most commonly used in second/third trimester # | ||||

| 75 g oral glucose tolerance test | 114 (83.3) | 80 (95.2) | 0.039 | 0.062 c |

| HbA1c | 9 (6.6) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Random plasma glucose/blood glucose level | 2 (1.5) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Fasting plasma glucose/blood glucose level | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 50 g glucose challenge test | 7 (5.1) | 2 (2.4) | ||

| Unsure | 3 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Gestational age of second/third trimester glucose screening | ||||

| <24 weeks | 3 (2.2) | 2 (2.3) | 0.44 | 0.56 d |

| 24–28 weeks | 128 (95.5) | 81 (93.1) | ||

| >28 weeks | 2 (1.5) | 2 (2.3) | ||

| Other | 1 (0.7) | 2 (2.3) | ||

| Proportion of women with hyperglycaemia in pregnancy seen postpartum for ongoing clinical care | ||||

| 0–20% | 54 (39.4) | 33 (39.3) | 0.11 | 0.074 e |

| 21–40% | 21 (15.3) | 7 (8.3) | ||

| 41–60% | 18 (13.1) | 8 (9.5) | ||

| 61–80% | 19 (13.9) | 13 (15.5) | ||

| 81–100% | 25 (18.2) | 23 (27.4) | ||

| Practitioners screening for diabetes postpartum after gestational diabetes *~ | ||||

| Yes | 40 (80.0) | 58 (77.3) | 0.003 | 0.003 f |

| No | 6 (12.0) | 1 (1.3) | ||

| Unsure | 4 (8.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| N/A—not viewed as part of practitioners’ role ^ | N/A | 16 (21.3) | ||

| Use of recalls for postpartum screening * | 44 (88.0) | 57 (96.6) | 0.43 | 0.43 f |

| Timing of postpartum screening after gestational diabetes * | ||||

| Up to and including 6 weeks | 25 (54.4) | 13 (24.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 f |

| After 6 weeks, up to and including 12 weeks | 13 (28.3) | 36 (66.7) | ||

| After 12 weeks, up to and including 6 months | 6 (13.0) | 3 (5.6) | ||

| After 6 months, up to and including 12 months | 2 (4.4) | 2 (3.7) | ||

| Screening test most commonly used postpartum after gestational diabetes * | ||||

| 75 g oral glucose tolerance test | 31 (64.6) | 40 (74.1) | 0.66 | 0.97 g |

| HbA1c | 12 (25.0) | 11 (20.4) | ||

| Random plasma glucose/blood glucose level | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Fasting plasma glucose/blood glucose level | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Unsure | 1 (2.1) | 3 (5.6) | ||

| Resuming HbA1c monitoring postpartum in women with pre-existing diabetes * | ||||

| Up to and including 12 weeks | 45 (81.8) | 28 (56.0) | 0.02 | 0.03 h |

| After 12 weeks | 10 (18.2) | 22 (44.0) | ||

| Made changes to own practice in caring for women with hyperglycaemia in pregnancy over the previous three years + | ||||

| Yes | N/A | 59 (64.1) | N/A | N/A |

| No | 33 (35.9) | |||

| Perceived support | ||||

| Perception of being well-supported in providing care for women with hyperglycaemia in pregnancy + | ||||

| Yes | N/A | 88 (77.9) | N/A | N/A |

| No | 11 (9.7) | |||

| Unsure | 14 (12.4) | |||

| Perception of change in support in providing care for women with hyperglycaemia in pregnancy + | ||||

| Improved | N/A | 65 (57.5) | N/A | N/A |

| Worsened | 5 (4.4) | |||

| No change | 11 (9.7) | |||

| Unsure | 32 (28.3) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

MacKay, D.; Maple-Brown, L.; Freeman, N.; Boyle, J.A.; Campbell, S.; McLean, A.; Corpus, S.; Whitbread, C.; Dokkum, P.V.; Connors, C.; et al. “It Empowers You to Empower Them”: Health Professional Perspectives of Care for Hyperglycaemia in Pregnancy Following a Multi-Component Health Systems Intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091139

MacKay D, Maple-Brown L, Freeman N, Boyle JA, Campbell S, McLean A, Corpus S, Whitbread C, Dokkum PV, Connors C, et al. “It Empowers You to Empower Them”: Health Professional Perspectives of Care for Hyperglycaemia in Pregnancy Following a Multi-Component Health Systems Intervention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(9):1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091139

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacKay, Diana, Louise Maple-Brown, Natasha Freeman, Jacqueline A. Boyle, Sandra Campbell, Anna McLean, Sumaria Corpus, Cherie Whitbread, Paula Van Dokkum, Christine Connors, and et al. 2024. "“It Empowers You to Empower Them”: Health Professional Perspectives of Care for Hyperglycaemia in Pregnancy Following a Multi-Component Health Systems Intervention" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 9: 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091139

APA StyleMacKay, D., Maple-Brown, L., Freeman, N., Boyle, J. A., Campbell, S., McLean, A., Corpus, S., Whitbread, C., Dokkum, P. V., Connors, C., Moore, E., Sinha, A., Cadet-James, Y., Boffa, J., Graham, S., Oats, J., Brown, A., McIntyre, H. D., & Kirkham, R. (2024). “It Empowers You to Empower Them”: Health Professional Perspectives of Care for Hyperglycaemia in Pregnancy Following a Multi-Component Health Systems Intervention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(9), 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091139