Predictors of Condom Use among College Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Procedure for Data Collection

2.3. Measures

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Center of Disease and Prevention Control. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2021. Atlanta, USA. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2021/default.htm (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Case, K.K.; Johnson, L.F.; Mahy, M.; Marsh, K.; Supervie, V.; Eaton, J.W. Summarizing the results and methods of the 2019 Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS HIV estimates. AIDS 2019, 33 (Suppl. S3), S197–S201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester-Arnal, R.; Giménez-García, C.; Ruiz-Palomino, E.; Castro-Calvo, J.; Gil-Llario, M.D. A Trend Analysis of Condom use in Spanish Young People over the Two Past Decades, 1999–2020. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 2299–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stover, J.; Teng, Y. The Impact of Condom Use on the HIV Epidemic. Gates Open Res. 2022, 5, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilton, L.; Palmer, R.T.; Maramba, L.C. Understanding HIV and STIs Prevention for College Students; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. YRBSS (Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System) Data Summary & Trends|DASH|CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/yrbs_data_summary_and_trends.htm (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Mthembu, Z.; Maharaj, P.; Rademeyer, S. “I am aware of the risks, I am not changing my behavior”: Risky sexual behavior of university students in a high-HIV context. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 2019, 18, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B.I.; Spindola, T.; Melo, L.D.; Marques, S.C.; Moraes, P.C.; Costa, C.M. Factors influencing condom misuse from the perspective of young university students. Rev. Enferm. Ref. 2022, 6, e21043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegolon, L.; Bortolotto, M.; Bellizzi, S.; Cegolon, A.; Bubbico, L.; Pichierri, G.; Mastrangelo, G.; Xodo, C.A. Survey on Knowledge, Prevention, and Occurrence of Sexually Transmitted Infections among Freshmen from Four Italian Universities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simelane, M.S.; Chemhaka, G.B.; Shabalala, F.S.; Simelane, P.T.; Vilakati, Z. Prevalence and determinants of inconsistent condom use among unmarried sexually active youth. a secondary analysis of the 2016–2017 Eswatini HIV incidence measurement survey. Afr. Health Sci. 2023, 23, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.; Matos, M.G. Equipa Aventura Social. HBSC/JUnP: Comportamentos de Saúde dos Jovens Universitários Portugueses; Aventura Social/FMH/ULisboa/FCT: Lisboa, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, R.A.; Charnigo, R.A.; Weathers, C.; Caliendo, A.M.; Shrier, L.A. Condom effectiveness against non-viral sexually transmitted infections: A prospective study using electronic daily diaries. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2012, 88, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabr, A.M.; Di Stefano, M.; Greco, P.; Santantonio, T.; Fiore, J.R. Errors in Condom Use in the Setting of HIV Transmission: A Systematic Review. Open AIDS J. 2020, 1, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copen, C.E. Condom Use During Sexual Intercourse among Women and Men Aged 15–44 in the United States: 2011–2015 National Survey of Family Growth. Natl. Health Stat. Rep. 2017, 105, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Smith, H.A.; Okpo, E.A.; Bull, E.R. Exploring psychosocial predictors of STI testing in University students. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davids, E.L.; Zembe, Y.; de Vries, P.J.; Mathews, C.; Swartz, A. Exploring condom use decision-making among adolescents: The synergistic role of affective and rational processes. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Palomino, E.; Ballester-Arnal, R.; Gil-Llario, M.D. Personality as a mediating variable in condom use among Spanish youth. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, M. Using the theory of planned behavior to determine the condom use behavior among college students. Am. J. Health Stud. 2015, 30, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshiekh, H.F.; Hoving, C.; de Vries, H. Psychosocial determinants of consistent condom use among university students in Sudan: Findings from a study using the Integrated Change Model. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, S.E.; Holland, K.J. Condom negotiation strategies as a mediator of the relationship between self-efficacy and condom use. J. Sex Res. 2013, 50, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesoff, E.D.; Dunkle, K.; Lang, D. The Impact of Condom Use Negotiation Self-Efficacy and Partnership Patterns on Consistent Condom Use Among College-Educated Women. Health Educ. Behav. 2016, 43, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza, L.; Richardson, J.L.; Ferguson, K.; Chou, C.-P.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Stacy, A.W. Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Correlates of Condom Use Among Young Adults from Continuation High Schools. Calif. J. Health Promot. 2017, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, D.E.; Koo, K.H.; Kilmer, J.R.; Blayney, J.A.; Lewis, M.A. Use of drinking protective behavioral strategies and sexual perceptions and behaviors in U.S. college students. J. Sex Res. 2015, 52, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilwein, T.M.; Looby, A. Predicting risky sexual behaviors among college student drinkers as a function of event-level drinking motives and alcohol use. Addict. Behav. 2018, 76, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.; Tomé, G.; Ramiro, L.; Guedes, F.; Matos, M. Razões para consumir álcool e a sua relação com os comportamentos sexuais entre jovens portugueses. Rev. Abe. Ciên. Soc. 2021, 9, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-Sheldon, L.A.; Carey, K.B.; Cunningham, K.; Johnson, B.T.; Carey, M.P. MASH Research Team. Alcohol Use Predicts Sexual Decision-Making: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Experimental Literature. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20 (Suppl. S1), S19–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, T.A.; Litt, D.M.; Davis, K.C.; Norris, J.; Kaysen, D.; Lewis, M.A. Growing Up, Hooking Up, and Drinking: A Review of Uncommitted Sexual Behavior and Its Association with Alcohol Use and Related Consequences among Adolescents and Young Adults in the United States. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperberg, A.; Padgett, J.E. Partner Meeting Contexts and Risky Behavior in College Students’ Other-Sex and Same-Sex Hookups. J. Sex Res. 2017, 54, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sumter, S.R.; Vandenbosch, L.; Ligtenberg, L. Love me Tinder: Untangling emerging adults’ motivations for using the dating application Tinder. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.R.; Reiber, C.; Massey, S.G.; Merriwether, A.M. Sexual Hookup Culture: A Review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2012, 16, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W.J.; Erausquin, J.T.; Nichols, T.R.; Tanner, A.E.; Brown-Jeffy, S. Relationship intentions, race, and gender: Student differences in condom use during hookups involving vaginal sex. J. Am. Coll. Health 2019, 67, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.F.; Silva, I.; Rodrigues, A.; Sá, L.; Beirão, D.; Rocha, P.; Santos, P. Young People Awareness of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Contraception: A Portuguese Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, W.D.; Ulasevich, A.; Hatheway, M.; Deperthes, B. Systematic Review of Peer-Reviewed Literature on Global Condom Promotion Programs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pender, N.; Murdaugh, C.; Parsons, M.A. Health Promotion in Nursing Practice, 6th ed.; Pearso: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 122–126. [Google Scholar]

- Vítor, J.F.; Lopes, M.V.; Ximenes, L.B. Análise do diagrama do modelo de promoção da saúde de Nola J. Pender. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2005, 18, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. Análise de Equações Estruturais, 3rd ed.; ReportNumber: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021; p. 410. [Google Scholar]

- Cragg, A.; Steenbeek, A.; Asbridge, M.; Andreou, P.; Langille, D. Sexually transmitted infection testing among heterosexual Maritime Canadian university students engaging in different levels of sexual risk taking. Can. J. Public. Health. 2016, 107, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, L.A.; Huedo-Medina, T.B.; Kalichman, S.C.; Pellowski, J.A.; Sagherian, M.J.; Warren, M.; Popat, A.R.; Johnson, B.T. Meta-analysis of single-session behavioral interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections: Implications for bundling prevention packages. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagherian, M.J.; Huedo-Medina, T.B.; Pellowski, J.A.; Eaton, L.A.; Johnson, B.T. Single-Session Behavioral Interventions for Sexual Risk Reduction: A Meta-Analysis. Ann. Behav. Med. 2016, 50, 920–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.J.; Ferreira, E.; Duarte, J.; Ferreira, M. Risk factors that influence sexual and reproductive health in Portuguese university students. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2018, 65, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefkowitz, E.S.; Vasilenko, S.A.; Wesche, R.; Maggs, J.L. Changes in diverse sexual and contraceptive behaviors across college. J. Sex Res. 2019, 56, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kritsotakis, G.; Georgiou, E.D.; Karakonstandakis, G.; Kaparounakis, N.; Pitsouni, V.; Sarafis, P. A longitudinal study of multiple lifestyle health risk behaviors among nursing students and non-nursing peers. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 26, e12852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oswalt, S.B.; Butler, S.; Sundstrom, B.; Hughes, C.M.L.; Robbins, C.P. Condoms on Campus: Understanding College Stu-dents’ Embarrassment, Self-Efficacy, and Beliefs about Distribution Programs. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2023, 50, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motamedi, M.; Merghati-Khoei, E.; Shahbazi, M.; Rahimi-Naghani, S.; Salehi, M.; Karimi, M.; Hajebi, A.; Khalajabadi-Farahani, F. Paradoxical attitudes toward premarital dating and sexual encounters in Tehran, Iran: A cross-sectional study. Reprod. Health 2016, 13, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piper, K.N.; Lambert, D.N.; Fuller, T.J. The Impact of Religious Participation and Religious Upbringing on the Sexual Behavior of Emerging Adults in the Southern United States. Sex. Cult. 2022, 26, 1711–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haglund, K.A.; Fehring, R.J. The association of religiosity, sexual education, and parental factors with risky sexual behaviors among adolescents and young adults. J. Relig. Health 2010, 49, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Oman, R.F.; Vesely, S.K.; Cheney, M.K.; Carroll, L. Prospective Associations Among Youth Religiosity and Religious Denomination and Youth Contraception Use. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, N.; Ejima, K.; Nishiura, H. Modelling the impact of correlations between condom use and sexual contact pattern on the dynamics of sexually transmitted infections. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 2018, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knox, J.; Yi, H.; Reddy, V.; Maimane, S.; Sandfort, T. The fallacy of intimacy: Sexual risk behaviour and beliefs about trust and condom use among men who have sex with men in South Africa. Psychol. Health Med. 2010, 15, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zizza, A.; Guido, M.; Recchia, V.; Grima, P.; Banchelli, F.; Tinelli, A. Knowledge, Information Needs and Risk Perception about HIV and Sexually Transmitted Diseases after an Education Intervention on Italian High School and University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, D.L.; Carvalho, A.C.; Lopes, D.; Garrido, M.V.; Visser, R.; Balzarini, R.N.; Prada, M. Health Safety Knowledge in Portugal and Spain. La Caixa Foundation. Project Selected in the Social Research Call 2020 (LCF/PR/SR20/52550001). 2022. Available online: https://oobservatoriosocial.fundacaolacaixa.pt/en/-/health-safety-knowledge-in-portugal-and-spain (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Sánchez-Ojeda, M.A.; Roldán, C.; Melguizo-Rodríguez, L.; de Luna-Bertos, E. Analysis of the Lifestyle of Spanish Undergraduate Nursing Students and Comparison with Students of Other Degrees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.J.; Ferreira, E.; Duarte, J.; Ferreira, M. Contraceptive behavior of Portuguese higher education students. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018, 71 (Suppl. S4), 1706–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, A.K.; Littlefield, A.K.; Talley, A.E.; Brown, J.L. Do individuals higher in impulsivity drink more impulsively? A pilot study within a high-risk sample of young adults. Addict. Behav. 2017, 65, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Questions | Internal Consistency Cronbach’s Alpha | Score Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived benefits * | “By adopting preventive behaviors, I prevent future reproductive health complications.” “For me, it is easy to use condoms in my daily life.” | A = 0.442 | Scores between 2 and 14 |

| Negative feelings * | “Getting condoms from the health centre is an embarrassing situation.” “Talking to healthcare professionals about contraceptive use-related issues can be embarrassing.” “Buying condoms is embarrassing because it exposes my privacy.” | A = 0.720 | Scores between 3 and 21 |

| Positive feelings * | “Using and discussing contraceptive methods is part of responsible sexuality.” “I feel better about myself when I use contraceptive methods.” | A = 0.420 | Scores between 2 and 14 |

| Self-efficacy for condom use ** | Self-efficacy for condom use, the Portuguese version of the Condom Use Self-Efficacy Scale (CUSES), consisting of 15 questions organized according to four factors (mechanisms, partner disapproval, assertiveness, intoxicants). | α = 0.820 | Scores between 0 and 60 |

| Interpersonal influences * | “People who are important to me advise me always to have and use condoms.” “It is important for sexual partners to talk about condom use.” | α = 0.594 | Scores between 2 and 14 |

| Situational influences * | “It is fun to have sexual experiences with casual partners.” “A good way to obtain sexual pleasure is to have sex under the influence of alcohol or drugs.” | α = 0.421 | Scores between 2 and 14 |

| Commitment to the plan of action * | “There is a high probability that I will use condoms over the next month.” “If I have sexual intercourse in the next month, I intend always to use condoms.” | α = 0.876 | Scores between 2 and 14 |

| Individual Characteristics and Experiences | Female Students | Male Students | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use | Don’t use | Use | Don’t use | Use | Don’t use | |

| n (%) | 369 (39.9) | 556 (60.1) | 221 (38.7) | 350 (61.3) | 590 (39.4) | 906 (60.6) |

| Age | ||||||

| ≤19 | 50.5 | 49.5 | 50.7 | 49.3 | 50.6 | 49.4 |

| 20–24 | 36.0 | 64.0 | 35.7 | 64.3 | 35.9 | 64.1 |

| ≥25 | 26.9 | 73.1 | 32.0 | 69.0 | 29.3 | 70.7 |

| Ӽ2 (p) | 20.535 (<0.001) | 11.623 (0.003) | 32.116 (<0.001) | |||

| Field of Study | ||||||

| Life Sciences and Healthcare | 42.32 | 57.8 | 38.6 | 61.4 | 40.9 | 59.1 |

| Human, Social, and Technology Sciences | 35.4 | 64.6 | 39.1 | 60.9 | 37.0 | 63.0 |

| Ӽ2 (p) | 3.962 (0.027) | 0.014 (0.906) | 2.234 (0.135) | |||

| Family Income | ||||||

| <2 minimum wage | 40.4 | 59.6 | 40.6 | 59.4 | 40.5 | 59.5 |

| 2–4 minimum wage | 37.9 | 62.1 | 36.5 | 63.5 | 37.3 | 62.7 |

| >4 minimum wage | 42.2 | 57.4 | 38.1 | 61.9 | 40.2 | 59.8 |

| Ӽ2 (p) | 0.756 (0.685) | 0.842 (0.656) | 1.246 (0.536) | |||

| Importance of Religion | ||||||

| Limited/none | 32.5 | 67.5 | 27.3 | 72.7 | 29.9 | 70.1 |

| Moderate | 37.3 | 62.7 | 40.0 | 60.0 | 38.4 | 61.6 |

| High | 43.2 | 56.8 | 41.3 | 58.7 | 42.5 | 57.5 |

| Ӽ2 (p) | 4.956 (0.084) | 5.066 (0.079) | 9.026 (0.011) | |||

| Condom Use at First Sexual Intercourse | ||||||

| Yes | 41.3 | 58.7 | 41.7 | 58.3 | 41.5 | 58.5 |

| No | 36.5 | 63.5 | 24.2 | 75.8 | 33.2 | 66.8 |

| Ӽ2 (p) | 1.827 (0.176) | 10.226 (0.001) | 7.748 (0.003) | |||

| Sexual Intercourse Within a Romantic Relationship | ||||||

| Yes | 39.1 | 60.9 | 34.9 | 65.1 | 37.7 | 62.3 |

| No | 54.2 | 45.8 | 54.0 | 46.0 | 54.0 | 46.0 |

| Ӽ2 (p) | 4.302 (0.038) | 13.861 (<0.001) | 16.099 (<0.001) | |||

| HPM Constructs | Female Students | Male Students | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use | Don’t Use | Use | Don’t Use | Use | Do Not Use | |

| Perceived Benefits of Action Scale range: 2–14 | 12.56 ± 2.27 | 11.46 ± 2.50 | 11.99 ± 2.36 | 11.09 ± 26.0 | 12.35 ± 2.32 | 11.32 ± 2.53 |

| Student’s t-test (p) | −6.861 (<0.001) | −−4.147 (<0.001) | −8.008 (<0.001) | |||

| Perceived Barriers to Action Scale range: 3–21 | 15.51 ± 4.62 | 16.33 ± 4.51 | 15.01 ± 4.40 | 15.78 ± 4.44 | 15.32 ± 4.54 | 16.11 ± 4.48 |

| Student’s t-test (p) | 2.675 (0.008) | 2.023 (0.044) | 3.327 (0.001) | |||

| Self-efficacy for Condom Use Scale range: 0–60 | 50.14 ± 7.56 | 48.93 ± 8.59 | 48.13 ± 9.47 | 47.86 ± 9.65 | 49.38 ± 8.38 | 48.52 ± 9.02 |

| Student’s t-test (p) | −2.248 (0.025) | −0.329 (0.742) | −1.895 (0.058) | |||

| Positive Feelings Scale range: 2–14 | 13.26 ± 1.59 | 12.65 ± 1.85 | 12.09 ± 2.05 | 11.03 ± 2.24 | 12.82 ± 1.86 | 12.03 ± 2.15 |

| Student’s t-test (p) | −5.370 (<0.001) | −5.699 (<0.001) | 36.501 (<0.001) | |||

| Negative Feelings Scale range: 2–14 | 2.90 ± 1.88 | 3.44 ± 2.09 | 3.52 ± 2.27 | 4.16 ± 2.53 | 3.13 ± 2.06 | 3.72 ± 2.29 |

| Student’s t-test (p) | 4.023 (<0.001) | 3.090 (0.002) | 5.088 (<0.001) | |||

| Interpersonal Influences Scale range: 2–14 | 8.84 ± 3.42 | 7.46 ± 3.57 | 10.91 ± 2.64 | 9.49 ± 3.21 | 9.61 ± 3.31 | 8.25 ± 3.57 |

| Student’s t-test (p) | −5.789 (<0.001) | −5.669 (<0.001) | −7.460 (<0.001) | |||

| Situational Influences Scale range: 2–14 | 11.95 ± 2.43 | 11.84 ± 2.64 | 9.09 ± 2.90 | 8.70 ± 3.06 | 10.87 ± 2.96 | 10.63 ± 3.20 |

| Student’s t-test (p) | −0.595 (0.552) | −1.528 (0.0127) | −1.517 (0.130) | |||

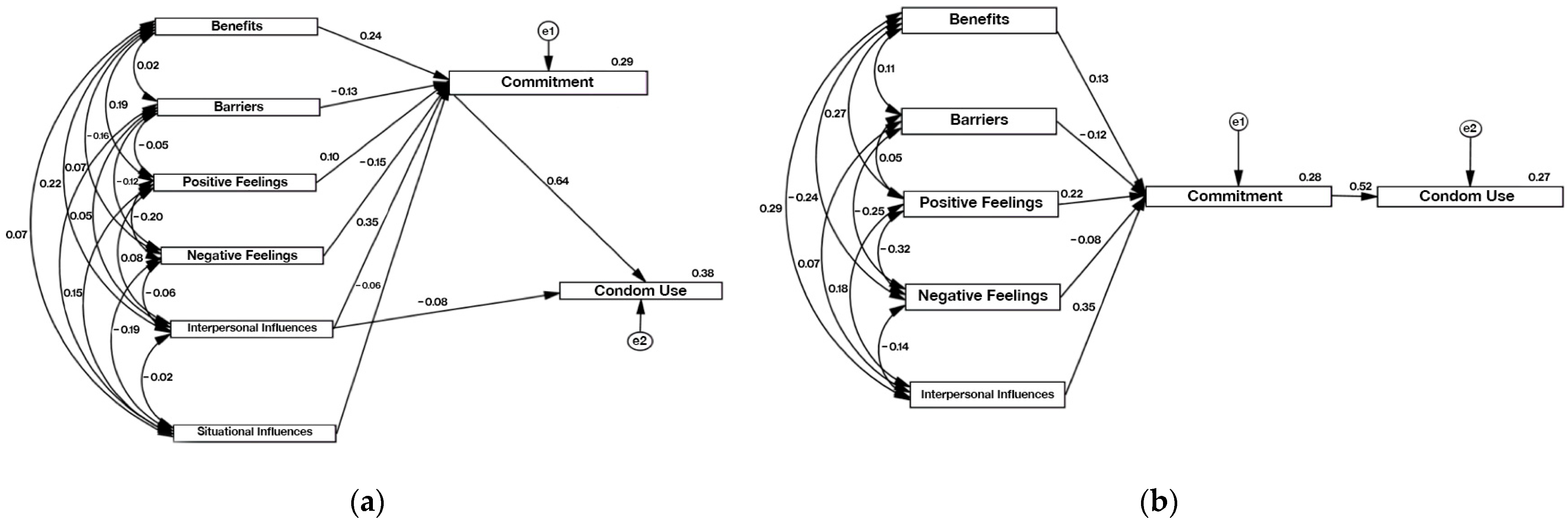

| Commitment to the Desired Behavior | HPM Constructs | C.R. | p | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female Students | ||||

| Commitment to condom use | Perceived benefits | 8.218 | *** | 0.239 |

| Perceived barriers | −4.497 | *** | −0.126 | |

| Positive feelings | 3.518 | *** | 0.100 | |

| Negative feelings | −5.201 | *** | −0.151 | |

| Interpersonal influences | 12.458 | *** | 0.354 | |

| Situational influences | −2.159 | 0.031 | −0.060 | |

| Health-promoting behavior | Interpersonal influences | −2.705 | 0.007 | −0.078 |

| Commitment to behavior | 22.433 | *** | 0.643 | |

| Male Students | ||||

| Commitment to condom use | Perceived benefits | 3.317 | *** | 0.129 |

| Perceived barriers | −3.175 | 0.001 | −0.120 | |

| Positive feelings | 5.568 | *** | 0.215 | |

| Negative feelings | −1.971 | 0.049 | −0.078 | |

| Interpersonal influences | 9.321 | *** | 0.350 | |

| Health-promoting behavior | Commitment to a plan of action | 14.280 | *** | 0.516 |

| Total Sample | ||||

| Commitment to condom use | Perceived benefits | 8.575 | *** | 0.200 |

| Perceived barriers | −5.719 | *** | −0.130 | |

| Positive feelings | 5.825 | *** | 0.136 | |

| Negative feelings | −5.269 | *** | −0.126 | |

| Interpersonal influences | 16.263 | 0.001 | 0.370 | |

| Situational influences | −2.238 | 0.25 | −0.051 | |

| Health-promoting behavior | Commitment to behavior | 24.031 | *** | 0.580 |

| Perceived barriers to action | −2.065 | 0.039 | −0.045 | |

| Positive feelings | 3.047 | 0.002 | 0.065 | |

| Interpersonal influences | −2.271 | 0.023 | −0.054 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, M.J.d.O.; Ferreira, E.M.S.; Ferreira, M.C. Predictors of Condom Use among College Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040433

Santos MJdO, Ferreira EMS, Ferreira MC. Predictors of Condom Use among College Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(4):433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040433

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Maria José de Oliveira, Elisabete Maria Soares Ferreira, and Manuela Conceição Ferreira. 2024. "Predictors of Condom Use among College Students" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 4: 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040433

APA StyleSantos, M. J. d. O., Ferreira, E. M. S., & Ferreira, M. C. (2024). Predictors of Condom Use among College Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(4), 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21040433