Abortion Experiences and Perspectives Amongst Migrants and Refugees: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

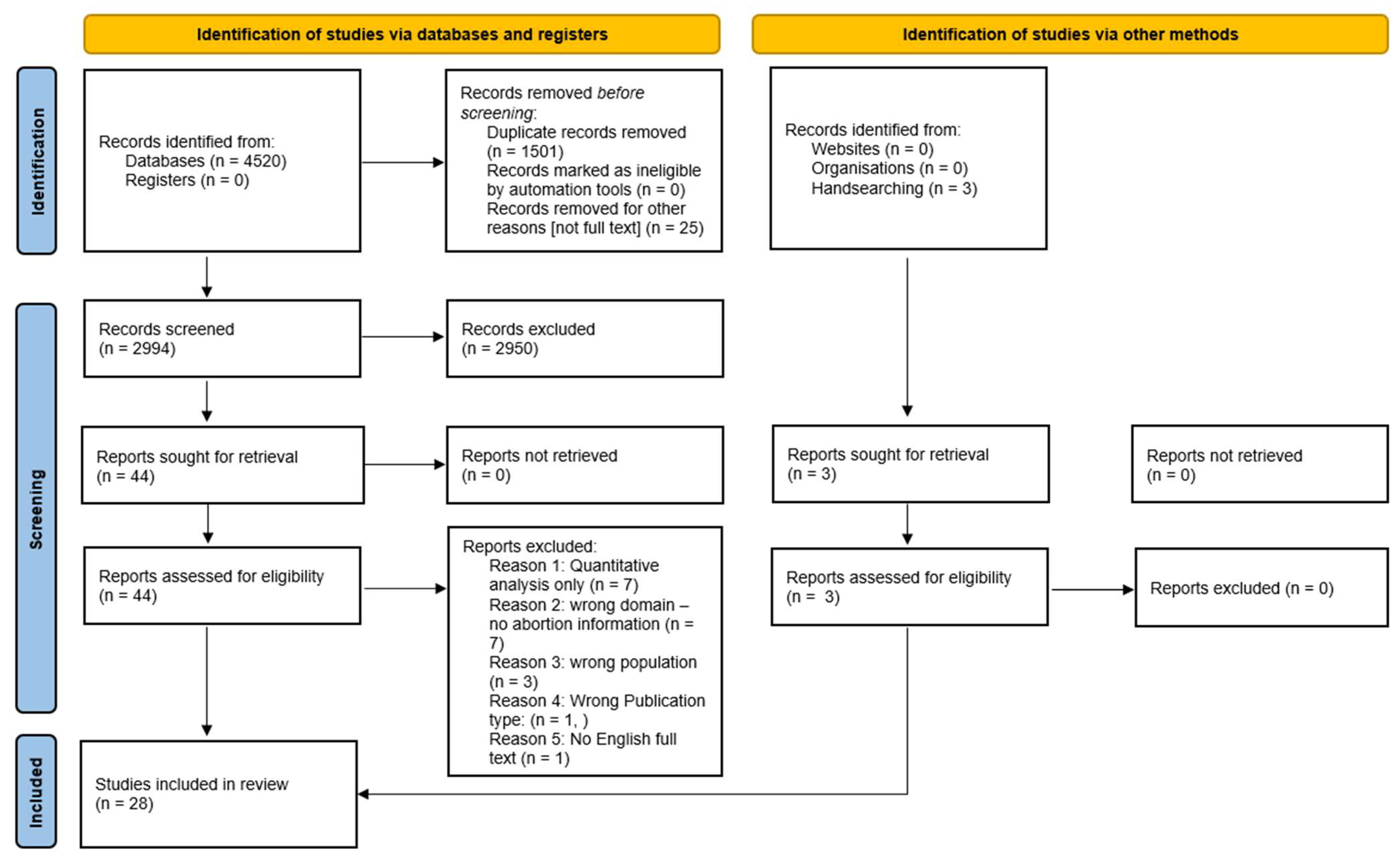

2. Materials and Methods

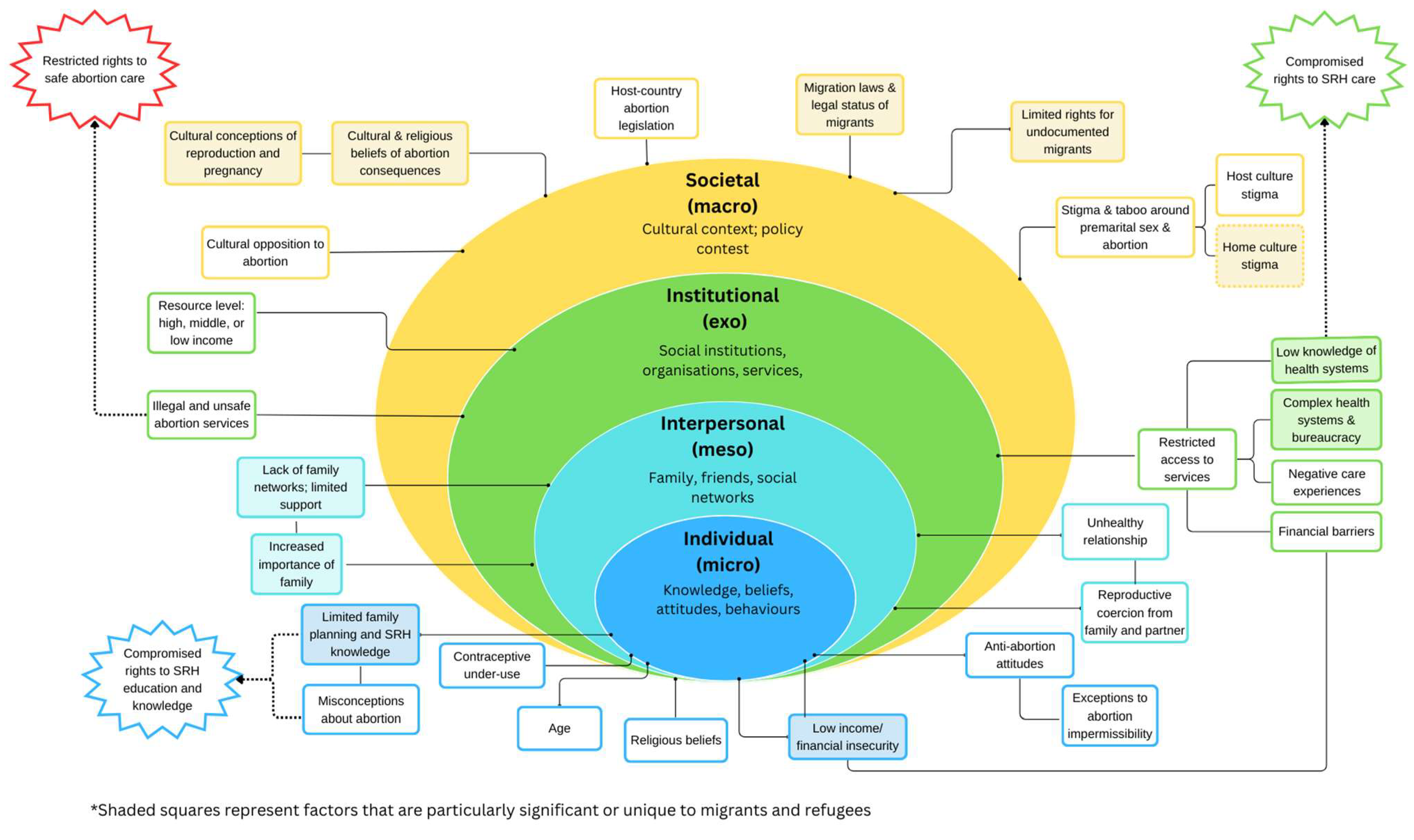

2.1. Search

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Quality Assessment

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

A Note on Gender

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

3.2. Attitudes, Perceptions and Beliefs towards Abortion and Abortion Permissibility

3.2.1. Attitudes and Perceptions

3.2.2. Knowledge and Beliefs Surrounding Abortion and Family Planning

3.2.3. Abortion Permissibility

3.3. Decision Making

3.3.1. Financial/Economic Factors

3.3.2. Sociocultural Factors

3.3.3. Contraceptive Failure and Under-Use

3.4. Accessing Abortion Care

3.4.1. Accessing Formal Care

3.4.2. Healthcare Experiences

3.4.3. Barriers to Accessing Care—Financial Barriers

3.4.4. Unregulated Abortions

4. Discussion

4.1. Attitudes and Beliefs

4.2. Knowledge

4.3. Decision Making

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Bearak, J.; Popinchalk, A.; Ganatra, B.; Moller, A.-B.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Beavin, C.; Kwok, L.; Alkema, L. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: Estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990–2019. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e1152–e1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateson, D.; McNamee, K.; Harvey, C. Medical abortion in primary care. Aust. Prescr. 2021, 44, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Abortion Care Guideline; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Coast, E.; Norris, A.H.; Moore, A.M.; Freeman, E. Trajectories of women’s abortion-related care: A conceptual framework. Social. Sci. Med. 2018, 200, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, L.; Solinger, R. Reproductive Justice: An Introduction; Reproductive Justice: A New Vision for the 21st Century; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Metusela, C.; Ussher, J.; Perz, J.; Hawkey, A.; Morrow, M.; Narchal, R.; Estoesta, J.; Monteiro, M. “In My Culture, We Don’t Know Anything About That”: Sexual and Reproductive Health of Migrant and Refugee Women. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 24, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napier-Raman, S.; Hossain, S.Z.; Lee, M.-J.; Mpofu, E.; Liamputtong, P.; Dune, T. Migrant and Refugee Youth Perspectives On Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in Australia: A Systematic Review. Sex. Health 2023, 20, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botfield, J.R.; Newman, C.E.; Kang, M.; Zwi, A.B. Talking to migrant and refugee young people about sexual health in general practice. Aust. J. General. Pract. 2018, 47, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengesha, Z.; Perz, J.; Dune, T.; Ussher, J. Refugee and migrant women’s engagement with sexual and reproductive health care in Australia: A socio-ecological analysis of health care professional perspectives. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussher, J.M.; Rhyder-Obid, M.; Perz, J.; Rae, M.; Wong, T.W.K.; Newman, P. Purity, Privacy and Procreation: Constructions and Experiences of Sexual and Reproductive Health in Assyrian and Karen Women Living in Australia. Sex. Cult. 2012, 16, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botfield, J.R.; Newman, C.E.; Bateson, D.; Haire, B.; Estoesta, J.; Forster, C.; Schulz Moore, J. Young migrant and refugee people’s views on unintended pregnancy and abortion in Sydney. Health Sociol. Rev. 2020, 29, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbemenu, K.; Hannan, M.; Kitutu, J.; Terry, M.A.; Doswell, W. “Sex Will Make Your Fingers Grow Thin and Then You Die”: The Interplay of Culture, Myths, and Taboos on African Immigrant Mothers’ Perceptions of Reproductive Health Education with Their Daughters Aged 10-14 Years. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanigaratne, S.; Wiedmeyer, M.L.; Brown, H.K.; Guttmann, A.; Urquia, M.L. Induced abortion according to immigrants’ birthplace: A population-based cohort study. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, S.; Desai, S.; Crowell, M.; Sedgh, G. Reasons why women have induced abortions: A synthesis of findings from 14 countries. Contraception 2017, 96, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lie, M.L.S.; Robson, S.C.; May, C.R. Experiences of abortion: A narrative review of qualitative studies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkman, M.; Rowe, H.; Hardiman, A.; Mallett, S.; Rosenthal, D. Reasons women give for abortion: A review of the literature. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2009, 12, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The EndNote Team. EndNote, Version 21; Clarivate: Philadephia, PA, USA, 2013.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP (Qualitative) Checklist [Online]. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Ahmed, S.; Hewison, J.; Green, J.M.; Cuckle, H.S.; Hirst, J.; Thornton, J.G. Decisions about testing and termination of pregnancy for different fetal conditions: A qualitative study of European White and Pakistani mothers of affected children. J. Genet. Couns. 2008, 17, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, G.; Tho, E.; Guroong, N.; Foster, A.M. To be, or not to be, referred: A qualitative study of women from Burma’s access to legal abortion care in Thailand. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnong, C.; Fellmeth, G.; Plugge, E.; Wai, N.S.; Pimanpanarak, M.; Paw, M.K.; Charunwatthana, P.; Nosten, F.; McGready, R. Adolescents’ perceptions and experiences of pregnancy in refugee and migrant communities on the Thailand-Myanmar border: A qualitative study. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belton, S.; Whittaker, A. Kathy Pan, sticks and pummelling: Techniques used to induce abortion by Burmese women on the Thai border. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 1512–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belton, S. Borders of fertility: Unplanned pregnancy and unsafe abortion in Burmese women migrating to Thailand. Health Care Women Int. 2007, 28, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, B.; Abu-El-Noor, M.A.; Nasser Ibrahim, A.-E.-N. Causes and consequences of unintended pregnancies in the Gaza Strip: A qualitative study. BMJ Sex. Reprod. Health 2019, 45, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeb-Sossa, N.; Billings, D.L. Barriers to abortion facing Mexican immigrants in North Carolina: Choosing folk healers versus standard medical options. Lat. Stud. 2014, 12, 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, C.P.; Kaflay, D.; Dowshen, N.; Miller, V.A.; Ginsburg, K.R.; Barg, F.K.; Yun, K. Attitudes and Beliefs Pertaining to Sexual and Reproductive Health Among Unmarried, Female Bhutanese Refugee Youth in Philadelphia. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fordyce, L. Responsible Choices: Situating Pregnancy Intention among Haitians in South Florida. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2012, 26, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gedeon, J.; Hsue, S.; Foster, A. “I came by the bicycle so we can avoid the police”: Factors shaping reproductive health decision-making on the Thailand-Burma border. Int. J. Popul. Stud. 2016, 2, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitsels-van der Wal, J.T.; Manniën, J.; Ghaly, M.M.; Verhoeven, P.S.; Hutton, E.K.; Reinders, H.S. The role of religion in decision-making on antenatal screening of congenital anomalies: A qualitative study amongst Muslim Turkish origin immigrants. Midwifery 2014, 30, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitsels-van der Wal, J.T.; Martin, L.; Manniën, J.; Verhoeven, P.; Hutton, E.K.; Reinders, H.S. A qualitative study on how Muslim women of Moroccan descent approach antenatal anomaly screening. Midwifery 2015, 31, e43–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, S.; Hoban, E.; Nevill, A. Unsafe abortion as a birth control method: Maternal mortality risks among unmarried Cambodian migrant women on the Thai-Cambodia border. Asia-Pac. J. Public Health 2012, 24, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hounnaklang, N.; Sarnkhaowkhom, C.; Bannatham, R. The beliefs and practices on sexual health and sexual transmitted infection prevention of Myanmar migrant workers in Thailand. Open Public Health J. 2021, 14, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khin, Y.P.; Nawa, N.; Fujiwara, T.; Surkan, P.J. Access to contraceptive services among Myanmar women living in Japan: A qualitative study. Contraception 2021, 104, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liamputtong, P. Abortion--it is for some women only! Hmong women’s perceptions of abortion. Health Care Women Int. 2003, 24, 230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Nara, R.; Banura, A.; Foster, A.M. Exploring Congolese refugees’ experiences with abortion care in Uganda: A multi-methods qualitative study. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2019, 27, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrach, B. Publicly funded abortion and marginalised people’s experiences in Catalunya: A longitudinal, comparative study. Anthropol. Action. 2020, 27, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, S.; Adams, V.; Ivey, S.; Nachtigall, R.D. “There is such a thing as too many daughters, but not too many sons”: A qualitative study of son preference and fetal sex selection among Indian immigrants in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remennick, L.I.; Segal, R. Socio-cultural context and women’s experiences of abortion: Israeli women and Russian immigrants compared. Cult. Health Sex. 2001, 3, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C.M.F.; Darsie, C.; da Silva, V.C.; Koetz, A.P.M.; Gama, A.F.; Dias, S.F. Displaced maternity: Pregnancy, voluntary abortion and women’s health for immigrant women in Portugal. Rev. Bras. Em Promocao Da Saude 2013, 26, 470–479. [Google Scholar]

- Royer, P.A.; Olson, L.M.; Jackson, B.; Weber, L.S.; Gawron, L.; Sanders, J.N.; Turok, D.K. “In Africa, There Was No Family Planning. Every Year You Just Give Birth”: Family Planning Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Somali and Congolese Refugee Women after Resettlement to the United States. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoevers, M.A.; van den Muijsenbergh, M.E.; Lagro-Janssen, A.L. Illegal female immigrants in The Netherlands have unmet needs in sexual and reproductive health. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 31, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tousaw, E.; La, R.K.; Arnott, G.; Chinthakanan, O.; Foster, A.M. “Without this program, women can lose their lives”: Migrant women’s experiences with the Safe Abortion Referral Programme in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Reprod. Health Matters 2017, 25, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousaw, E.; Moo, S.; Arnott, G.; Foster, A.M. “It is just like having a period with back pain”: Exploring women’s experiences with community-based distribution of misoprostol for early abortion on the Thailand-Burma border. Contraception 2018, 97, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.; Moon, S.S.; Kim, M.; Kim, K.S. The study on the motivation of sex-selective abortion among Indian immigrants in U.S.A. Int. J. Bio-Sci. Bio-Technol. 2015, 7, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udmuangpia, T.; Haggstrom-Nordin, E.; Worawong, C.; Tanglakmankhonge, K.; Bloom, T. A Qualitative study: Perceptions Regarding Adolescent Pregnancy Among A Group of Thai Adolescents in Sweden. Pac. Rim Int. J. Nurs. Res. 2017, 21, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Reproductive Rights. The World’s Abortion Laws. 2023. Available online: https://reproductiverights.org/maps/worlds-abortion-laws/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NVivo, Version 12; QSR International Pty Ltd.: Burlington, NJ, USA, 2020.

- The World Bank. WDI—The World by Income and Region. Available online: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/the-world-by-income-and-region.html (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- Wray, A.; Ussher, J.M.; Perz, J. Constructions and experiences of sexual health among young, heterosexual, unmarried Muslim women immigrants in Australia. Cult. Health Sex. 2014, 16, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanschmidt, F.; Linde, K.; Hilbert, A.; Riedel- Heller, S.G.; Kersting, A. Abortion Stigma: A Systematic Review. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2016, 48, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokubal, P.; Corcuera, I.; Balil, J.M.; Frischer, S.R.; Kayemba, C.N.; Kurinczuk, J.J.; Opondo, C.; Nair, M. Abortion decision-making process trajectories and determinants in low—And middle-income countries: A mixed-methods systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 54, 101694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehnström Loi, U.; Lindgren, M.; Faxelid, E.; Oguttu, M.; Klingberg-Allvin, M. Decision-making preceding induced abortion: A qualitative study of women’s experiences in Kisumu, Kenya. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagoto, S.L.; Palmer, L.; Horwitz-Willis, N. The Next Infodemic: Abortion Misinformation. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e42582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assifi, A.R.; Berger, B.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Khosla, R.; Ganatra, B. Women’s Awareness and Knowledge of Abortion Laws: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, S.E.; Isa, G.P.; Isumbisho Mazambi, E.; Giuffrida, M.M.; Jayne Kulkarni, M.; Perera, S.M. Community perceptions of the impact of war on unintended pregnancy and induced abortion in Protection of Civilian sites in Juba, South Sudan. Glob. Public Health 2022, 17, 2176–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, S.E.; Steven, V.J.; Deitch, J.; Dumas, E.F.; Gallagher, M.C.; Martinez, S.; Morris, C.N.; Rafanoharana, R.V.; Wheeler, E. “You must first save her life”: Community perceptions towards induced abortion and post-abortion care in North and South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2019, 27, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Inclusion | Exclusion | Key Terms/Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Global | ||

| Language | English | Non-English | English only selected |

| Date | Published January 2000–December 2022 | Published before 2000 | Date restrictions: 1 January 2000– |

| Population | Studies including migrant and/or refugee populations; second-generation migrants; international students | Predominantly non-migrant/refugee study populations; internally displaced people; domestic migrants; service providers | Migrant* OR refugee* OR immigrant* OR ‘asylum seeker*’ OR ‘ethnic minorit*’ AND |

| Outcome/domain | Studies examining migrant and refugee abortion experiences, attitudes and/or perspectives; broader studies examining migrant and refugee SRH attitudes and/or experiences that include data on abortion | Studies examining non-migrant perspectives; Studies not examining participant perspectives or experiences | Abortion OR termination OR ‘termination of pregnancy’ OR ‘induced abortion’ OR ‘unplanned pregnancy’ |

| Study design | Primary qualitative studies; grey literature | Quantitative studies; Abstract-only studies, reviews, opinion pieces |

| Author (Year) | Data Collection Method | Setting | Setting Income Level | Abortion Legality * | Outcome/Domain | Relevant Sample Size * | Participant Residency/Migration Status | Population Background | CASP Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed (2008) [20] | Interviews; self-completion questionnaire | United Kingdom | High income | Permitted on broad social or economic grounds * | Decision making regarding prenatal testing and termination for genetic conditions between Pakistani and white European mothers | 10 (19 in total study) | Migrants: first generation (n = 5), second generation (n = 5) | Pakistani | 8 |

| Arnot (2017) [21] | Interviews | Thailand | Middle income | Restricted at time of publishing (to preserve health/social economic grounds); currently permitted on request | Experiences with safe abortion referral program | 14 | Cross-border **, refugees, migrants | Burmese | 9 |

| Asnong (2018) [22] | Interviews; focus group discussions | Mae La Refugee Camp, Mae Ker Thai clinic: Thailand-Burma border | Middle income | Restricted at time of publishing; currently permitted on request | Refugee and migrant adolescents’ perceptions and experiences of pregnancy | 20 female (pregnant adolescents); 20 male (husbands of pregnant adolescents, adolescent boys, non-pregnant adolescent girls) | Refugees, migrants | Burmese | 8 |

| Belton and Whitaker (2007) [23] | Ethnography: interviews; focus group discussions; free-list activities | Tak Province, Thailand | Middle income | Restricted at time of publishing; currently permitted on request | Barriers to contraceptive access; motivation and means for termination | 43 inpatients with post-abortion complications, 10 male partners, 10 health workers, 20 community members | Migrants (women post-abortion, partners, community members and lay midwives) | Burmese | 8 |

| Belton (2007) [24] | Ethnography: interviews; focus group discussions; free-list activities | Tak Province, Thailand | Middle income | Restricted at time of publishing; currently permitted on request | Barriers in contraceptive access; traditional techniques to terminate pregnancy | 43 inpatients with post-abortion complications, 10 male partners, 10 health workers, 20 community members | Migrants | Burmese | 8 |

| Botfield (2020) [11] | Interviews | Sydney, Australia | High income | Permitted on request | Migrant and refugee youth experiences and perspectives on unintended pregnancy and abortion | 27 | Refugees, migrants | Mixed: East and Southeast Asian, African, South American, Mediterranean, Middle-Eastern | 9 |

| Böttcher (2019) [25] | Focus group discussions | Gaza strip | Middle income | Permitted to save the pregnant person’s life | Causes and consequences of unintended pregnancy | 21 | Refugees | Palestinian | 8 |

| Deeb-Sossa (2014) [26] | Ethnography: participant observation; interviews | North Carolina, United States | High income | Legal at time of publishing; 12-week restriction from July 2023 | Barriers to abortion access | 12 | Migrants | Mexican | 9 |

| Dhar (2017) [27] | Interviews | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States | High income | On request at time of publishing; currently accessible, with restrictions and no protections | Sexual and reproductive health attitudes and beliefs of unmarried, young Bhutanese women | 14 | Refugees | Bhutanese | 8 |

| Fordyce (2012) [28] | Interviews; ethnographic | South Florida, United States | High income | On request at time of publishing; currently protected, with restrictions | Family planning; unintended pregnancy | 27 | Migrants | Haitian | 8 |

| Gedeon (2016) [29] | Interviews | Tak Province, Thailand | Middle income | Restricted at time of publishing; currently permitted on request, gestational limit 20 weeks | Barriers to reproductive healthcare; sexual and reproductive decision making | 31 | Refugees, migrants | Burmese | 9 |

| Gitsels-van der Wal (2014) [30] | Interviews | The Netherlands | High income | Permitted on request | Role of religion (Islam) on decision making regarding prenatal anomaly screening and termination | 10 | Migrants: first generation (n = 6), second generation (n = 4) | Turkish | 9 |

| Gitsels-van der Wal (2015) [31] | Interviews | The Netherlands | High income | Permitted on request | Role of religion (Islam) on decision making regarding prenatal anomaly screening and termination | 12 | Migrants: first generation (n = 6), second generation (n = 6) | Moroccan | 8 |

| Hegde (2012) [32] | Ethnography: interviews, semi-structured questionnaires | Thai-Cambodia border | Middle income | Restricted at time of publishing; Currently permitted on request, gestational limit 20 weeks | attitudes and practices towards unsafe abortions; abortion as contraceptive method | 10 interviewees; 15 questionnaire respondents (30 questionnaire participants in total) | Migrants/cross-border ** | Cambodian | 7 |

| Hounnaklang (2021) [33] | Observation, field notes, in-depth interviews | Surat Thani province, Thailand | Middle income | Permitted on request, gestational limit 20 week | Sexual and reproductive health attitudes and beliefs; practices | 22 | Migrants | Myanmar women | 8 |

| Khin (2021) [34] | Interviews | Japan | High income | Permitted on broad social or economic grounds | Access to reproductive healthcare | 17 | Mixed residency status, including dependents, work visas, permanent/long-term residents | Myanmar women | 8 |

| Liamputtong (2003) [35] | In-depth interviews, participant observation | Melbourne, Australia | High income | Permitted on request; available but criminal at time of publishing; decriminalised 2008 | Cultural practices and beliefs regarding abortion | 27 | Refugees, residing in Australia for 1–10+ years; spent minimum 1 year in Thai refugee camp | Hmong women | 8 |

| Nara (2019) [36] | Interviews; focus group discussions (FGDs) | Kampala and the Nakivale Refugee Settlement, Uganda | Low income | Permitted to save the pregnant person’s life | Reproductive healthcare; contraception and abortion/post-abortion services | 21 interviewees; 36 in FGDs | Refugees | Congolese women | 9 |

| Ostrach (2020) [37] | Interviews; rapid ethnographic assessment | Catalunya, Spain | High income | Permitted on request | Experiences with legal, publicly funded abortion | 13 (28 total participants) | Migrants | Not provided | 9 |

| Puri (2011) [38] | Interviews | California, New York, New Jersey, The United States | High income | Permitted on request at time of publishing; currently protected | Sex-selective abortion practices and experiences | 65 | Migrants | Indian women; Sikh (65%), Hindu (22%), (12%) Muslim (1%) | 7 |

| Remennick (2001) [39] | Interviews | Israel | High income | Permitted preserve health | Abortion experiences of native Israelis and recent Russian immigrants | 25 (48 total participants) | Recent migrants | Russian women (former Soviet Union) | 9 |

| Rocha (2013) [40] | Focus group discussions and demographic questionnaire | Portugal | High income | Permitted on request | Sexual and reproductive health; maternity, pregnancy, induced abortion | 35 | Migrants | Brazil and Portuguese-speaking African countries (Lusophone): 15 Brazilians, 20 Africans | 7 |

| Royer (2020) [41] | Focus group discussions | The United States | High income | Permitted on request at time of publishing; currently dependent on state law | Family planning knowledge, attitudes, and practices | 66 | Refugees | Somali and Congolese women | 10 |

| Schoevers (2010) [42] | Semi-structured interviews | The Netherlands | High income | Permitted on request | Sexual and reproductive health problems and needs | 100 | Illegal immigrants | Mixed: Eastern Europe, Yugoslavia, former USSR; Middle East and North Africa; China, Mongolia; South America; Philippines; Surinam | 8 |

| Tousaw (2017) [43] | Interviews | Mae Sot, Thailand | Middle income | Restricted at time of publishing; currently permitted on request, gestational limit 20 weeks | Experiences of and perceptions on Safe Abortion Referral Program (SARP) | 22 | Documented (n = 10) and undocumented (n = 12) migrants | Burmese | 9 |

| Tousaw (2018) [44] | Interviews | Thailand-Burma border | Middle income | Restricted at time of publishing; currently permitted on request, gestational limit 20 weeks | Experiences of and perspectives on community-based misoprostol program | 16 | Cross-border, refugees, migrants | Burmese | 9 |

| Tucker (2015) [45] | Interviews | The United States | High income | Permitted on request at time of publishing; currently dependent on state law | Motivations for sex-selective abortions | 20 | Migrants | Indian | 8 |

| Udmuangpia (2017) [46] | Focus group discussions | Sweden | High income | Permitted on request | Perspectives on sexual behaviour and pregnancy | 18 | Adolescent migrants | Thai | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Napier-Raman, S.; Hossain, S.Z.; Mpofu, E.; Lee, M.-J.; Liamputtong, P.; Dune, T. Abortion Experiences and Perspectives Amongst Migrants and Refugees: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21030312

Napier-Raman S, Hossain SZ, Mpofu E, Lee M-J, Liamputtong P, Dune T. Abortion Experiences and Perspectives Amongst Migrants and Refugees: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(3):312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21030312

Chicago/Turabian StyleNapier-Raman, Sharanya, Syeda Zakia Hossain, Elias Mpofu, Mi-Joung Lee, Pranee Liamputtong, and Tinashe Dune. 2024. "Abortion Experiences and Perspectives Amongst Migrants and Refugees: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 3: 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21030312

APA StyleNapier-Raman, S., Hossain, S. Z., Mpofu, E., Lee, M.-J., Liamputtong, P., & Dune, T. (2024). Abortion Experiences and Perspectives Amongst Migrants and Refugees: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(3), 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21030312