Adapting the Stress First Aid Model for Frontline Healthcare Workers during COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Peer Support Intervention

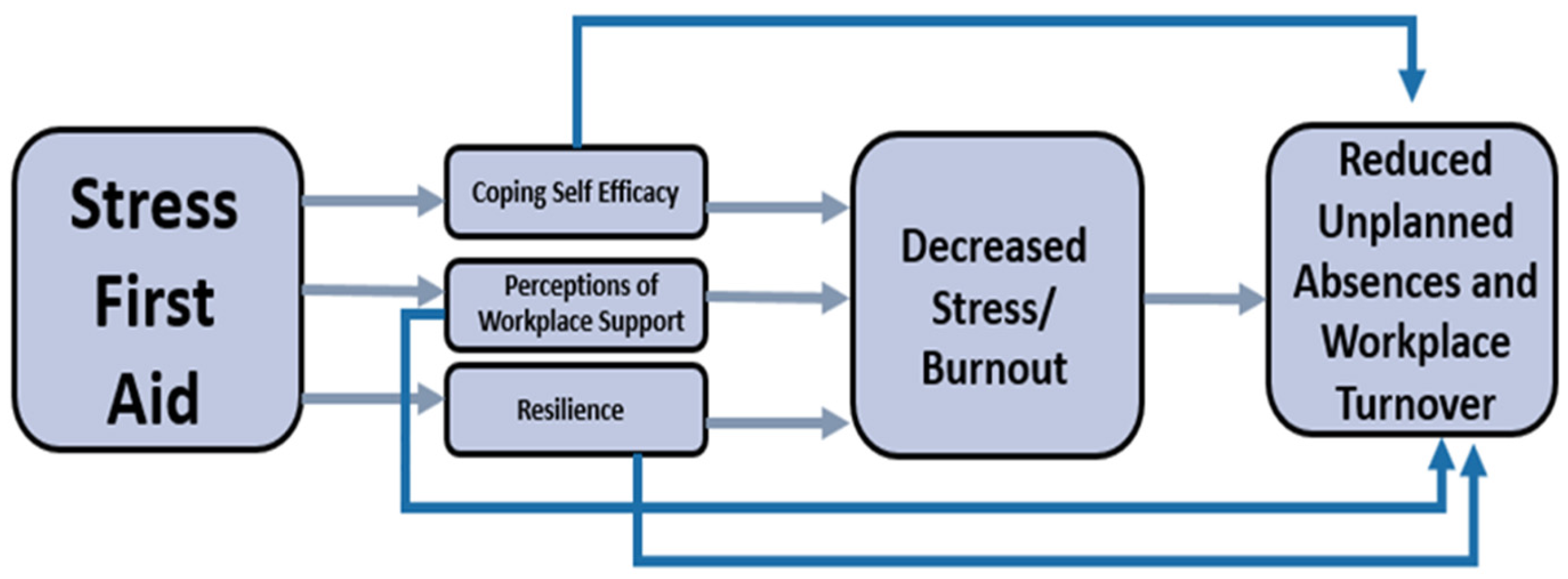

1.2. Stress First Aid

1.3. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. SFA Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Proximal Outcomes

2.3.2. Distal Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

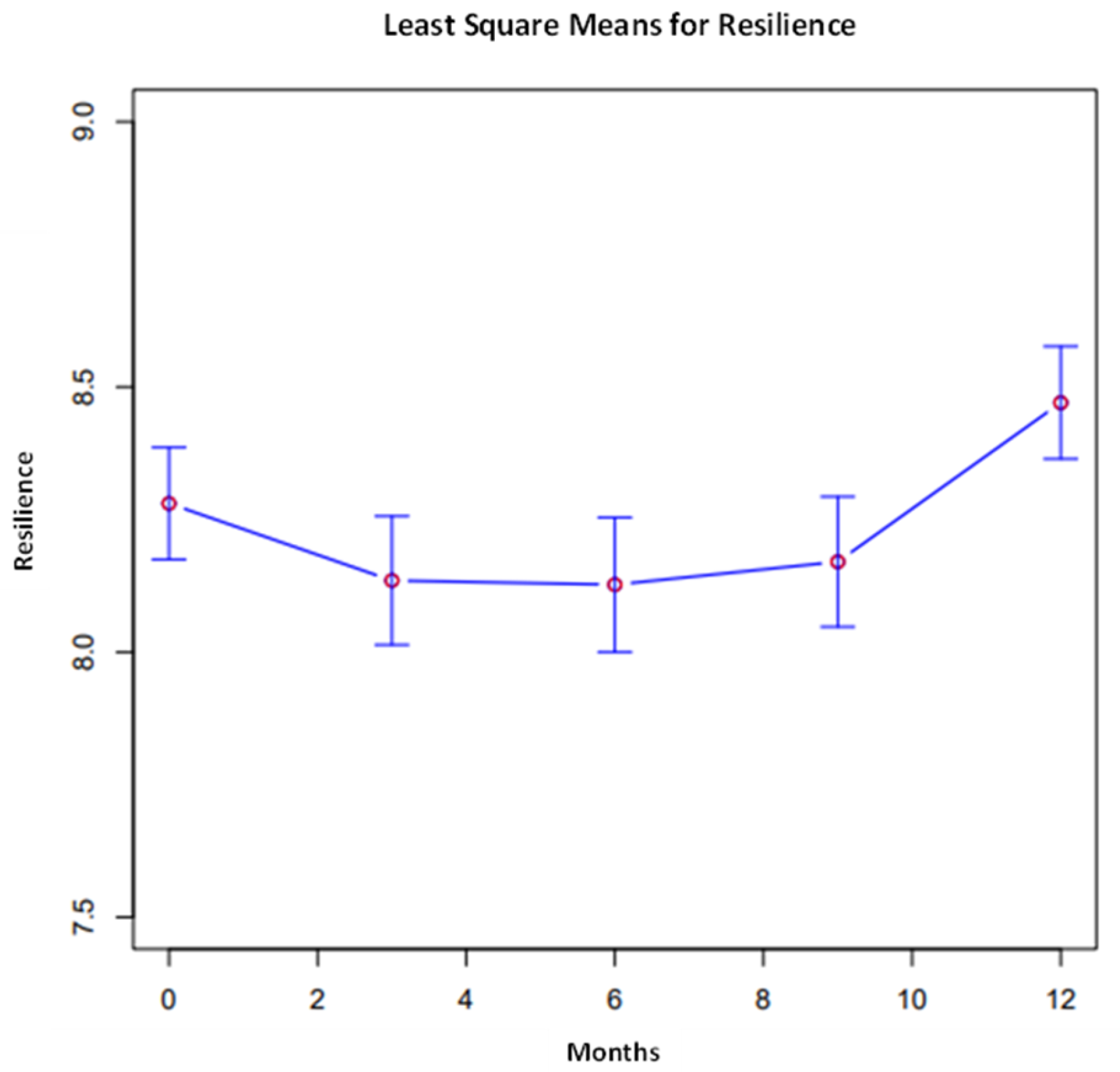

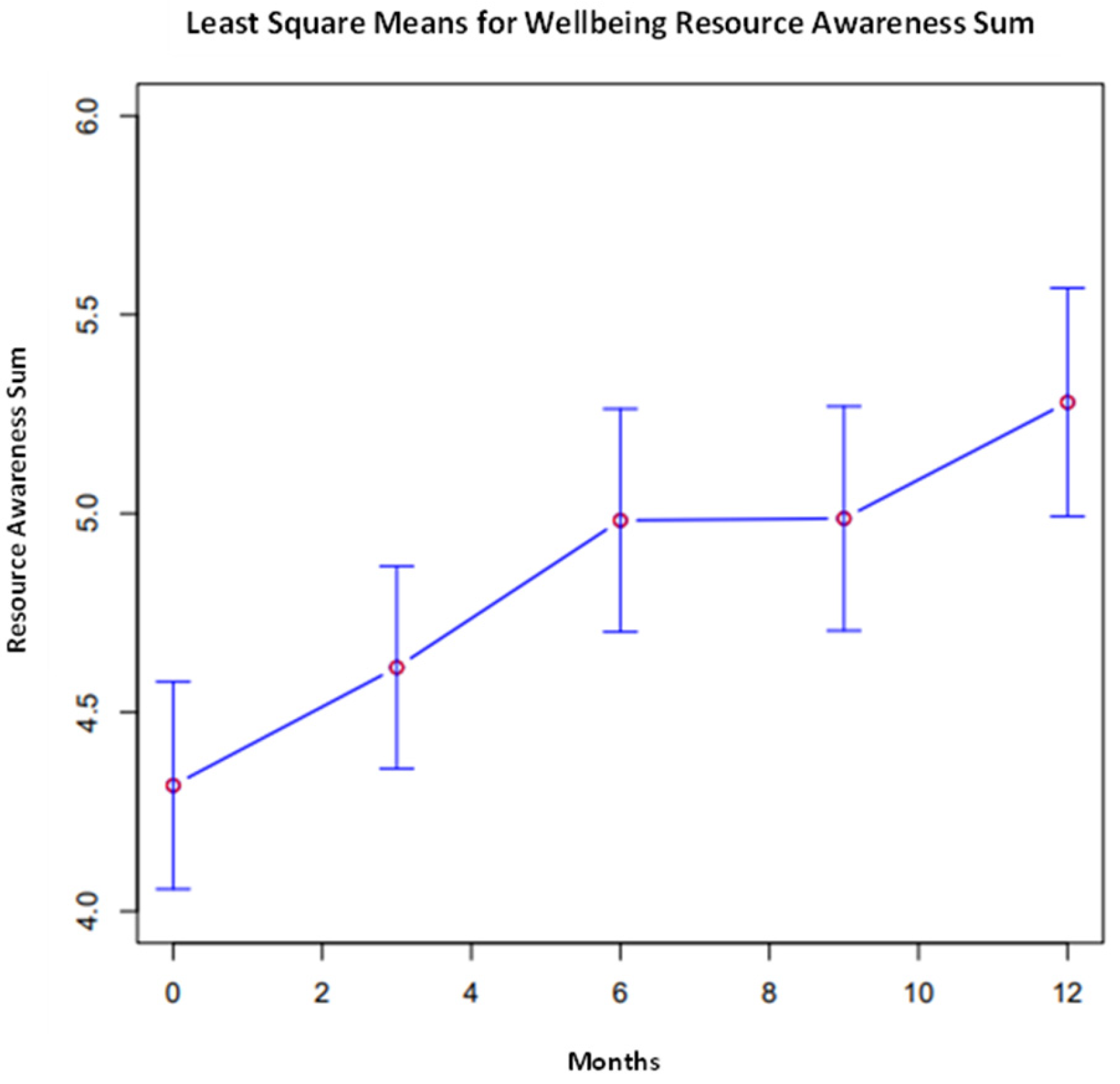

3.1. Longitudinal Descriptive of Study Variables

3.2. Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) Analysis of Study Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ripp, J.; Peccoralo, L.; Charney, D. Attending to the Emotional Well-Being of the Health Care Workforce in a New York City Health System During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 1136–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, M.L.R.; Almeida, H.G.; Esmeraldo, J.D.A.; Nobre, C.B.; Pinheiro, W.R.; de Oliveira, C.R.T.; da Costa Sousa, I.; Lima, O.M.M.L.; Lima, N.N.R.; Moreira, M.M.; et al. When Health Professionals Look Death in the Eye: The Mental Health of Professionals Who Deal Daily with the 2019 Coronavirus Outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushal, A.; Kumar, S.; Mehta, M.; Singh, M. Study of Stress among Health Care Professionals: A Systemic Review. Int. J. Res. Found. Hosp. Health Care Adm. 2018, 6, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-J. Psychological First-Aid Experiences of Disaster Health Care Workers: A Qualitative Analysis. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019, 14, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpacioglu, S.; Gurler, M.; Cakiroglu, S. Secondary Traumatization Outcomes and Associated Factors among the Health Care Workers Exposed to the COVID-19. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 67, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, C.; Foghi, C.; Dell’Oste, V.; Cordone, A.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Bui, E.; Dell’Osso, L. PTSD Symptoms in Healthcare Workers Facing the Three Coronavirus Outbreaks: What Can We Expect after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olfson, M.; Cosgrove, C.M.; Wall, M.M.; Blanco, C. Suicide Risks of Health Care Workers in the US. JAMA 2023, 330, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T.; Ripp, J.; Trockel, M. Understanding and Addressing Sources of Anxiety among Health Care Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA 2020, 323, 2133–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firew, T.; Sano, E.D.; Lee, J.W.; Flores, S.; Lang, K.; Salman, K.; Greene, M.C.; Chang, B.P. Protecting the Front Line: A Cross-Sectional Survey Analysis of the Occupational Factors Contributing to Healthcare Workers’ Infection and Psychological Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the USA. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fateminia, A.; Hasanvand, S.; Goudarzi, F.; Mohammadi, R. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Frontline Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Relationship with Occupational Burnout. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2022, 17, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Women Hold 76% of All Health Care Jobs, Gaining in Higher-Paying Occupations. Census.gov. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/08/your-health-care-in-womens-hands.html (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Labrague, L.J.; de Los Santos, J.A.A. Fear of COVID-19, Psychological Distress, Work Satisfaction and Turnover Intention among Frontline Nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 29, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrague, L.J.; De Los Santos, J.A.A. COVID-19 Anxiety among Front-Line Nurses: Predictive Role of Organisational Support, Personal Resilience and Social Support. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1653–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, R.M.; El-Shafei, D.A. Occupational Stress, Job Satisfaction, and Intent to Leave: Nurses Working on Front Lines during COVID-19 Pandemic in Zagazig City, Egypt. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 28, 8791–8801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perego, G.; Cugnata, F.; Brombin, C.; Milano, F.; Mazzetti, M.; Taranto, P.; Preti, E.; Di Pierro, R.; De Panfilis, C.; Madeddu, F.; et al. Analysis of Healthcare Workers’ Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from a Three-Wave Longitudinal Study. J. Health Psychol. 2023, 28, 1279–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacca, A.; Minò, M.V.; Longo, R.; Lucisani, G.; Solomita, B.; Franza, F. The Emotional Impact on Mental Health Workers in the Care of Patients with Mental Disorders in the Pandemic and Post COVID-19 Pandemic: A Measure of “Burnout” and “Compassion Fatigue”. Psychiatr. Danub. 2023, 35, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kang, L.; Ma, S.; Chen, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Yao, L.; Bai, H.; Cai, Z.; Xiang Yang, B.; et al. Impact on Mental Health and Perceptions of Psychological Care among Medical and Nursing Staff in Wuhan during the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease Outbreak: A Cross-Sectional Study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaffey, B.L.; Mackin, D.M.; Rosen, J.; Schwartz, R.M.; Taioli, E.; Gonzalez, A. The Disaster Worker Resiliency Training Program: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 94, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, R.M.; McCann-Pineo, M.; Bellehsen, M.; Singh, V.; Malhotra, P.; Rasul, R.; Corley, S.S.; Jan, S.; Parashar, N.; George, S.; et al. The Impact of Physicians’ COVID-19 Pandemic Occupational Experiences on Mental Health. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 64, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Young, J.Q.; Malhotra, P.; McCann-Pineo, M.; Rasul, R.; Corley, S.S.; Yacht, A.C.; Friedman, K.; Barone, S.; Schwartz, R.M. Evaluating Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Physicians in a Large Health System in New York. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2022, 77, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechter, A.; Diaz, F.; Moise, N.; Anstey, D.E.; Ye, S.; Agarwal, S.; Birk, J.L.; Brodie, D.; Cannone, D.E.; Chang, B.; et al. Psychological Distress, Coping Behaviors, and Preferences for Support among New York Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, A.; Ji, P.; Nackerud, L. Predictors of Secondary Traumatic Stress among Social Workers: Supervision, Income, and Caseload Size. J. Soc. Work 2018, 19, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.-L. Peer Support within a Health Care Context: A Concept Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2003, 40, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C.D.; Ling, J. “Are We Doing Enough”: An Examination of the Utilization of Employee Assistance Programs to Support the Mental Health Needs of Employees During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Insur. Regul. 2020, 39, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellins, C.A.; Mayer, L.E.S.; Glasofer, D.R.; Devlin, M.J.; Albano, A.M.; Nash, S.S.; Engle, E.; Cullen, C.; Ng, W.Y.K.; Allmann, A.E.; et al. Supporting the Well-Being of Health Care Providers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The CopeColumbia Response. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2020, 67, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albott, C.S.; Wozniak, J.R.; McGlinch, B.P.; Wall, M.H.; Gold, B.S.; Vinogradov, S. Battle Buddies: Rapid Deployment of a Psychological Resilience Intervention for Health Care Workers During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 131, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DePierro, J.; Katz, C.L.; Marin, D.; Feder, A.; Bevilacqua, L.; Sharma, V.; Hurtado, A.; Ripp, J.; Lim, S.; Charney, D. Mount Sinai’s Center for Stress, Resilience and Personal Growth as a Model for Responding to the Impact of COVID-19 on Health Care Workers. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, L.; Berna, F.; Nourry, N.; Severac, F.; Vidailhet, P.; Mengin, A.C. Efficacy of an Online Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Program Developed for Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The REduction of STress (REST) Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 2020, 21, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, A.R. Cultivating Deliberate Resilience during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.S.; Di Nota, P.M.; Groll, D.; Carleton, R.N. Peer Support and Crisis-Focused Psychological Interventions Designed to Mitigate Post-Traumatic Stress Injuries among Public Safety and Frontline Healthcare Personnel: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buselli, R.; Corsi, M.; Baldanzi, S.; Chiumiento, M.; Del Lupo, E.; Dell’Oste, V.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Massimetti, G.; Dell’Osso, L.; Cristaudo, A.; et al. Professional Quality of Life and Mental Health Outcomes among Health Care Workers Exposed to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, H.; Bermingham, F.; Johnson, G.; Tabner, A. Mitigating the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Workers: A Digital Learning Package. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine. Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. In Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, A.; Campbell, P.; Cheyne, J.; Cowie, J.; Davis, B.; McCallum, J.; McGill, K.; Elders, A.; Hagen, S.; McClurg, D.; et al. Interventions to Support the Resilience and Mental Health of Frontline Health and Social Care Professionals during and after a Disease Outbreak, Epidemic or Pandemic: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. Cochrane Libr. 2020, 11, CD013779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, W.P.; Westphal, R.J.; Watson, P.J.; Litz, B.T. Combat and Operational Stress First Aid: Caregiver Training Manual; U.S. Navy, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, P.; Taylor, V.; Gist, R.; Elvander, E.; Leto, F.; Martin, B.; Tanner, J.; Vaught, D.; Nash, W.; Westphal, R.; et al. Stress First Aid for Firefighters and Emergency Medical Services Personnel; National Fallen Firefighters Foundation: Emmitsburg, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, P.J.; Brymer, M.J.; Bonanno, G.A. Postdisaster Psychological Intervention since 9/11. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahnke, S.A.; Watson, P.; Leto, F.; Jitnarin, N.; Kaipust, C.M.; Hollerbach, B.S.; Haddock, C.K.; Poston, W.S.C.; Gist, R. Evaluation of the Implementation of the NFFF Stress First Aid Intervention in Career Fire Departments: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Meredith, L.S.; Farmer, C.M.; Ahluwalia, S.C.; Chen, P.G.; Bouskill, K.; Han, B.; Qureshi, N.; Dalton, S.; Watson, P.; et al. Protecting the Mental and Physical Well-Being of Frontline Health Care Workers during COVID-19: Study Protocol of a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2022, 117, 106768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, C.P.; Betsworth, D.; Bihday, C.; Daman, M.C.; Davis, C.A.; Kaysen, D.; Rosen, C.S.; Saxby, D.; Smith, A.E.; Spinelli, S.; et al. Helping the Helpers: Adaptation and Evaluation of Stress First Aid for Healthcare Workers in the Veterans Health Administration During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Workplace Health Saf. 2023, 71, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.J. Application of the Five Elements Framework to the Covid Pandemic. Psychiatry MMC 2021, 84, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Watson, P.; Bell, C.C.; Bryant, R.A.; Brymer, M.J.; Friedman, M.J.; Friedman, M.; Gersons, B.P.R.; de Jong, J.T.V.M.; Layne, C.M.; et al. Five Essential Elements of Immediate and Mid-Term Mass Trauma Intervention: Empirical Evidence. Psychiatry Interpers. Biol. Process. 2007, 70, 283–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fida, R.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Leiter, M.P. The Protective Role of Self-Efficacy against Workplace Incivility and Burnout in Nursing: A Time-Lagged Study. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Borgogni, L.; Consiglio, C.; Read, E. The Effects of Authentic Leadership, Six Areas of Worklife, and Occupational Coping Self-Efficacy on New Graduate Nurses’ Burnout and Mental Health: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero, M.D.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Gázquez, J.J. Analysis of the Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy and Self-Esteem on the Effect of Workload on Burnout’s Influence on Nurses’ Plans to Work Longer. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisanti, R.; van der Doef, M.; Maes, S.; Lombardo, C.; Lazzari, D.; Violani, C. Occupational Coping Self-Efficacy Explains Distress and Well-Being in Nurses beyond Psychosocial Job Characteristics. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, D.; Rancati, A. Managing Complexity (and Chaos) in Times of Crisis. A Field Guide for Decision Makers Inspired by the Cynefin Framework. Publ. Off. Eur. Union 2021, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a New Resilience Scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.-Y.; Zeger, S.L. Longitudinal Data Analysis Using Generalized Linear Models. Biometrika 1986, 73, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzmaurice, G.M.; Laird, N.M.; Ware, J.H. Applied Longitudinal Analysis, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Positive Tests over Time, by Region and County. Available online: https://coronavirus.health.ny.gov/positive-tests-over-time-region-and-county (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Ghanimi, H.M.A.; Yasear, S.A. A Cognitive Agent Model of Burnout for Front-Line Healthcare Professionals in Times of COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst. 2022, 15, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, L.E.; Medvedev, O.N. Investigating State and Trait Aspects of Resilience Using Generalizability Theory. Psychol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriharan, A.; Ratnapalan, S.; Tricco, A.C.; Lupea, D.; Ayala, A.P.; Pang, H.; Lee, D.D. Occupational Stress, Burnout, and Depression in Women in Healthcare During COVID-19 Pandemic: Rapid Scoping Review. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2020, 1, 596690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| RN—Registered Nurse | 96 | 36.1 |

| Mental Health Nursing Staff | 90 | 33.8 |

| Unit Receptionist | 20 | 7.5 |

| ANM—Assistant Nurse Manager | 14 | 5.3 |

| Other | 12 | 4.5 |

| Nursing Administrator | 9 | 3.4 |

| NM—Nurse Manager | 9 | 3.4 |

| Scheduler | 4 | 1.5 |

| PCA—Patient Care Associate | 3 | 1.1 |

| Director | 3 | 1.1 |

| Nursing Attendant | 2 | 0.8 |

| Nurse Educator | 2 | 0.8 |

| NA—Nursing Assistant | 1 | 0.4 |

| Certified Nursing Assistant | 1 | 0.4 |

| Total | 266 | 100 |

| Baseline | 3-Month Follow-Up | 6-Month Follow-Up | 9-Month Follow-Up | 12-Month Follow-Up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | |

| SFA Self-Efficacy * | 9.10 | 0.15 | 9.15 | 0.13 | 9.36 | 0.14 | 9.21 | 0.14 | 9.54 | 0.14 |

| Resilience ** | 8.28 | 0.11 | 8.13 | 0.12 | 8.13 | 0.13 | 8.17 | 0.12 | 8.47 | 0.11 |

| Perceptions of Organizational Support | 7.89 | 0.16 | 7.94 | 0.15 | 7.99 | 0.15 | 8.16 | 0.16 | 8.29 | 0.14 |

| Stress | 2.18 | 0.07 | 2.11 | 0.06 | 2.07 | 0.07 | 2.14 | 0.07 | 2.10 | 0.07 |

| Burnout | 5.11 | 0.13 | 4.99 | 0.14 | 5.20 | 0.17 | 5.85 | 0.15 | 4.82 | 0.14 |

| Resource Awareness ** | 4.32 | 0.26 | 4.61 | 0.25 | 4.98 | 0.28 | 4.99 | 0.28 | 5.28 | 0.29 |

| Any Resource Utilization (OR; 95% CI) | 0.27 | (0.18–0.40) | 0.28 | (0.19–0.43) | 0.31 | (0.20–0.48) | 0.33 | (0.21–0.53) | 0.40 | (0.27–0.60) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bellehsen, M.H.; Cook, H.M.; Shaam, P.; Burns, D.; D’Amico, P.; Goldberg, A.; McManus, M.B.; Sapra, M.; Thomas, L.; Wacha-Montes, A.; et al. Adapting the Stress First Aid Model for Frontline Healthcare Workers during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21020171

Bellehsen MH, Cook HM, Shaam P, Burns D, D’Amico P, Goldberg A, McManus MB, Sapra M, Thomas L, Wacha-Montes A, et al. Adapting the Stress First Aid Model for Frontline Healthcare Workers during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(2):171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21020171

Chicago/Turabian StyleBellehsen, Mayer H., Haley M. Cook, Pooja Shaam, Daniella Burns, Peter D’Amico, Arielle Goldberg, Mary Beth McManus, Manish Sapra, Lily Thomas, Annmarie Wacha-Montes, and et al. 2024. "Adapting the Stress First Aid Model for Frontline Healthcare Workers during COVID-19" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 2: 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21020171

APA StyleBellehsen, M. H., Cook, H. M., Shaam, P., Burns, D., D’Amico, P., Goldberg, A., McManus, M. B., Sapra, M., Thomas, L., Wacha-Montes, A., Zenzerovich, G., Watson, P., Westphal, R. J., & Schwartz, R. M. (2024). Adapting the Stress First Aid Model for Frontline Healthcare Workers during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(2), 171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21020171