Transforming Chronic Pain Care Through Telemedicine: An Italian Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Be cancer survivors with a history of chemotherapy or radiation treatment and diagnosed with complex chronic pain.

- Present a pain intensity greater than 4/10 on the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS).

- Agree to participate in the digital approach for remote monitoring.

- Be over 18 years of age.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Patients with NRS pain less than 4.

- Patients with metastatic neoplasms.

- Patients aged under 18 years.

2.3. Screening, Recruitment, and Verification Process

2.4. Demographic Characteristics and Data Collection

2.5. Telemedicine Interventions

- Secure patient access: Patients could access the platform through a dedicated link, and healthcare providers used personal credentials to ensure data privacy and security.

- Patient data management: The platform allowed for the creation of individualized patient profiles, where treatment plans and medical histories were regularly updated.

- Two-way communication and mobile app integration: The platform enabled two-way communication between patients and healthcare providers via email, and patients could use a mobile app to manage telehealth visits, send data, and receive updates.

- Caregiver support: Caregivers also had access to relevant information on the platform to support patient care.

2.6. Data Collection and Outcome Measures

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

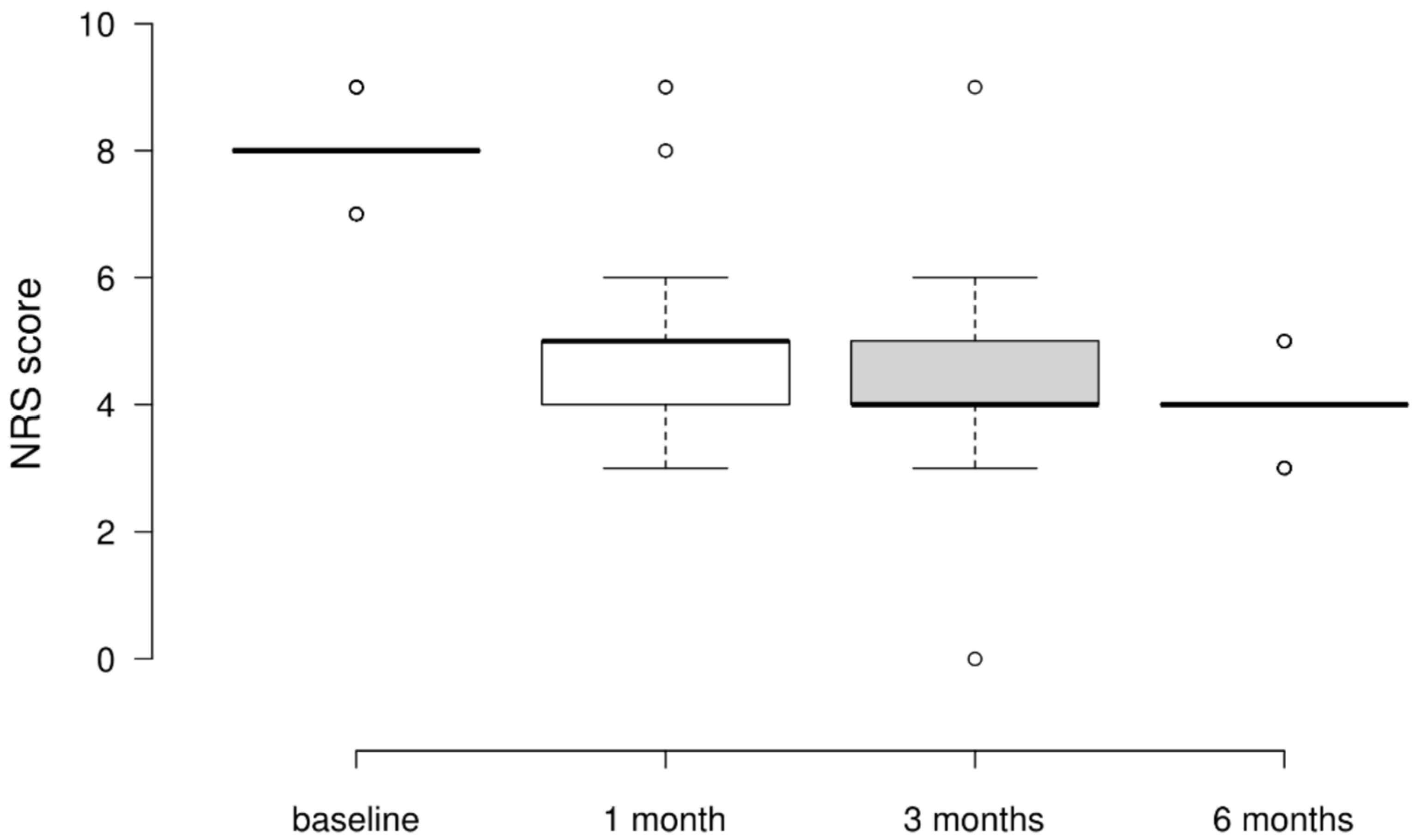

3.2. NRS Scores

3.3. BPI Worst Pain Scores

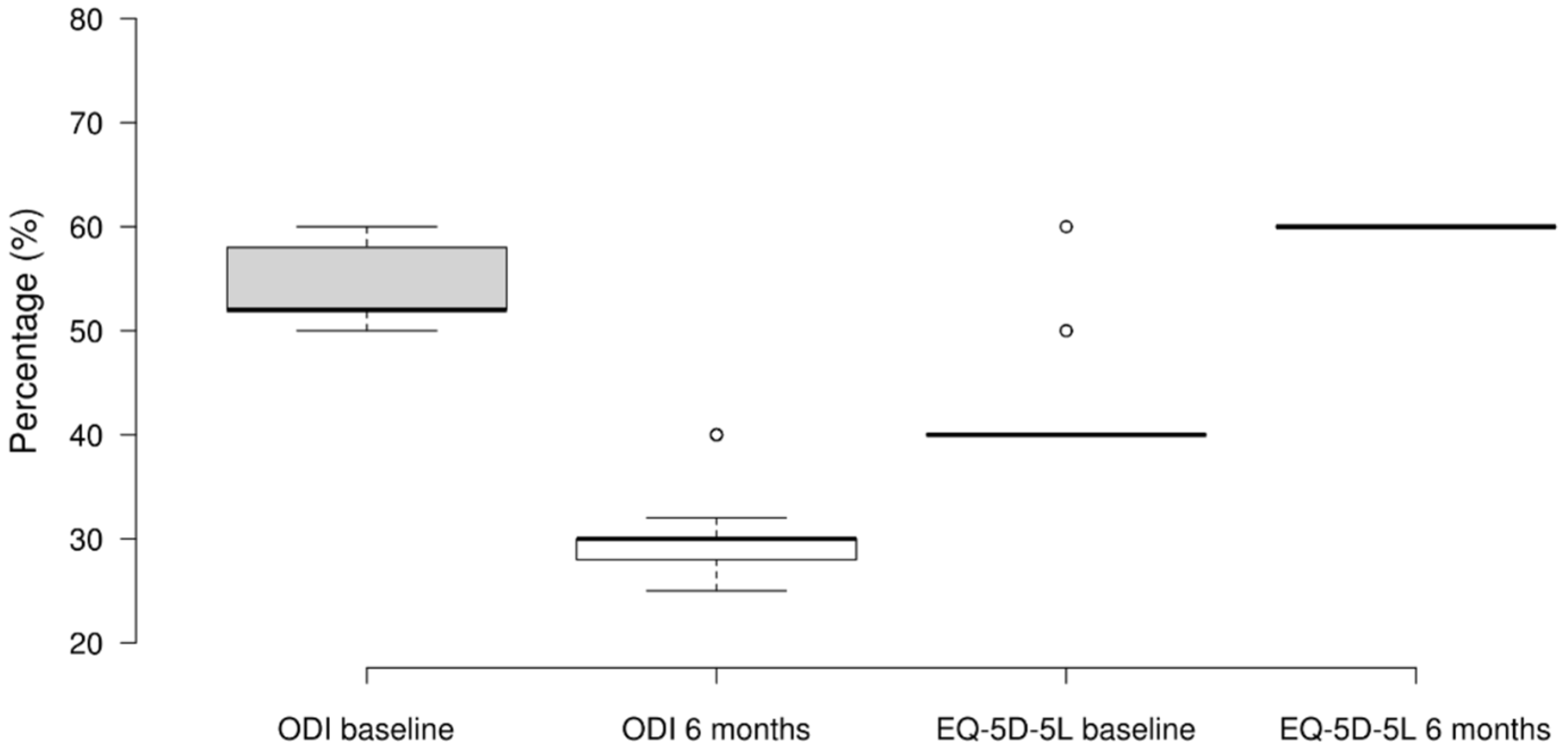

3.4. ODI and EQ-5D-5L

4. Discussion

- The heterogeneity of available solutions creates barriers to sharing common patient data, thereby engendering redundancy and escalating healthcare costs.

- The lack of interconnectivity among telemedicine services across different levels of care impedes a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach to patient treatment.

- An absence of evidence supporting clinical and cost-effectiveness results in suboptimal deployment and inefficiency.

- Privacy regulations, practical recommendations, and the lack of telemedicine services in the essential levels of care within the public health system present significant challenges.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Todd, K.H.; Cowan, P.; Kelly, N. 114: Chronic or Recurrent Pain in the Emergency Department: A National Telephone Survey of Patient Experience. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2007, 50, S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Treede, R.D.; Rief, W.; Barke, A.; Aziz, Q.; Bennett, M.I.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Evers, S.; Finnerup, N.B.; First, M.B.; et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain 2019, 160, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barke, A.; Korwisi, B.; Rief, W. Chronic Pain in the ICD-11: New Diagnoses That Clinical Psychologists Should Know About. Clin. Psychol. Eur. 2022, 4, e9933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Trewern, L.; Jackman, J.; McCartney, D.; Soni, A. Chronic pain: Definitions and diagnosis. BMJ 2023, 381, e076036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.P.; Vase, L.; Hooten, W.M. Chronic pain: An update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet 2021, 397, 2082–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.S.; McGee, S.J. Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borsook, D.; Kalso, E. Transforming pain medicine: Adapting to science and society. Eur. J. Pain 2013, 17, 1109–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.E.E.; Nicolson, K.P.; Smith, B.H. Chronic pain: A review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, e273–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikard, S.M.; Strahan, A.E.; Schmit, K.M.; Guy, G.P., Jr. Chronic Pain Among Adults—United States, 2019–2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Low Back Pain Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e316–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, G.; Gensini, G.; Canonico, P.L.; Delle Fave, G.; Aprile, P.L.; Mandelli, A.; Nicolosi, G. Dolore in Italia. Analisi della situazione. Proposte operative. Recent. Progress. Med. 2012, 103, 133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Latina, R.; De Marinis, M.G.; Giordano, F.; Osborn, J.F.; Giannarelli, D.; Di Biagio, E.; Varrassi, G.; Sansoni, J.; Bertini, L.; Baglio, G.; et al. Epidemiology of Chronic Pain in the Latium Region, Italy: A Cross-Sectional Study on the Clinical Characteristics of Patients Attending Pain Clinics. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2019, 20, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuercher, M.; D’Alessandro, L.N.; Brown, S.C.; Lorenzo, A.; Levin, D. Resolution of post-traumatic chronic testicular pain in a pediatric patient after microsurgical denervation of the spermatic cord: A case report. Can. J. Anaesth. 2021, 68, 1690–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilloni, A.; Nati, G.; Maggiolini, P.; Romanelli, A.; Carbone, G.; Giannarelli, D.; Terrenato, I.; Marinis, M.G.D.; Rossi, A.; D’Angelo, D.; et al. Chronic non-cancer pain in primary care: An Italian cross-sectional study. Signa Vitae 2020, 17, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koesling, D.; Kieselbach, K.; Bozzaro, C. Chronic pain and society: Sociological analysis of a complex interconnection. Schmerz 2019, 33, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Yamada, K.; Iseki, M.; Karasawa, Y.; Murakami, Y.; Enomoto, T.; Kikuchi, N.; Chiba, S.; Hara, A.; Yamaguchi, K.; et al. Insomnia and caregiver burden in chronic pain patients: A cross-sectional clinical study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suso-Ribera, C.; Yakobov, E.; Carriere, J.S.; Garcia-Palacios, A. The impact of chronic pain on patients and spouses: Consequences on occupational status, distribution of household chores and care-giving burden. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 1730–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H.; Tetsunaga, T.; Tetsunaga, T.; Misawa, H.; Oda, Y.; Takao, S.; Nishida, K.; Ozaki, T. Factors Influencing Caregiver Burden in Chronic Pain Patients: A Retrospective Study. Medicine 2022, 101, e30802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, D.J.; Dryland, A.; Rashid, U.; Tuck, N.L. The Determinants and Effects of Chronic Pain Stigma: A Mixed Methods Study and the Development of a Model. J. Pain 2022, 23, 1749–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunde, C.E.; Fisher, E.; Donovan, E.; Serbic, D.; Sieberg, C.B. Cutting the cord? Parenting emerging adults with chronic Pain. Paediatr. Neonatal Pain 2022, 4, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duenas, M.; Ojeda, B.; Salazar, A.; Mico, J.A.; Failde, I. A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. J. Pain Res. 2016, 9, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamse, C.; Dekker-Van Weering, M.G.; van Etten-Jamaludin, F.S.; Stuiver, M.M. The effectiveness of exercise-based telemedicine on pain, physical activity and quality of life in the treatment of chronic pain: A systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 2018, 24, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eze, N.D.; Mateus, C.; Cravo Oliveira Hashiguchi, T. Telemedicine in the OECD: An umbrella review of clinical and cost-effectiveness, patient experience and implementation. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmark, L.; Sunde, H.F.; Fors, E.A.; Kennair, L.E.O.; Sayadian, A.; Backelin, C.; Reme, S.E. Associations between pain intensity, psychosocial factors, and pain-related disability in 4285 patients with chronic pain. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, B.W.; Haugh, S.; O’Connor, L.; Francis, K.; Dwyer, C.P.; O’Higgins, S.; Egan, J.; McGuire, B.E. An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Modalities Used to Deliver Electronic Health Interventions for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review with Network Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e11086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stronge, A.J.; Rogers, W.A.; Fisk, A.D. Human factors considerations in implementing telemedicine systems to accommodate older adults. J. Telemed. Telecare 2007, 13, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M.; Marinangeli, F.; Vittori, A.; Scala, C.; Piccinini, M.; Braga, A.; Miceli, L.; Vellucci, R. Open Issues and Practical Suggestions for Telemedicine in Chronic Pain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M.; Schiavo, D.; Grizzuti, M.; Romano, M.C.; Coluccia, S.; Bimonte, S.; Cuomo, A. Implementation of a Hybrid Care Model for Telemedicine-based Cancer Pain Management at the Cancer Center of Naples, Italy: A Cohort Study. In Vivo 2023, 37, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasoon, J.; Urits, I.; Viswanath, O.; Kaye, A.D. Pain Management and Telemedicine: A Look at the COVID Experience and Beyond. Health Psychol. Res. 2022, 10, 38012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahezi, S.E.; Duarte, R.; Kim, C.; Sehgal, N.; Argoff, C.; Michaud, K.; Luu, M.; Gonnella, J.; Kohan, L. An Algorithmic Approach to the Physical Exam for the Pain Medicine Practitioner: A Review of the Literature with Multidisciplinary Consensus. Pain Med. 2022, 23, 1489–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, A.; O’Shea, D.; Power, C. Advanced clinical prioritisation in an Irish, tertiary, chronic pain management service: An audit of outcomes. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 192, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, T.M.; Mendoza, T.R.; Sit, L.; Passik, S.; Scher, H.I.; Cleeland, C.; Basch, E. The Brief Pain Inventory and its “pain at its worst in the last 24 hours” item: Clinical trial endpoint considerations. Pain Med. 2010, 11, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, G.; Jensen, M.P.; Thornby, J.I.; Shanti, B.F. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant Pain. J. Pain 2004, 5, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonezzi, C.; Nava, A.; Barbieri, M.; Bettaglio, R.; Demartini, L.; Miotti, D.; Paulin, L. Validazione della versione italiana del Brief Pain Inventory nei pazienti con dolore cronico. Minerva Anestesiol. 2002, 68, 607–611. [Google Scholar]

- Balestroni, G.; Bertolotti, G. EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D): An instrument for measuring quality of life. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2012, 78, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbank, J.C.; Pynsent, P.B. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine 2000, 25, 2940–2952; discussion 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birrenbach, T.; Buhlmann, F.; Exadaktylos, A.K.; Hautz, W.E.; Muller, M.; Sauter, T.C. Virtual Reality for Pain Relief in the Emergency Room (VIPER)—A prospective, interventional feasibility study. BMC Emerg. Med. 2022, 22, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikka, N.; Shu, L.; Ritchie, B.; Amdur, R.L.; Pourmand, A. Virtual Reality-Assisted Pain, Anxiety, and Anger Management in the Emergency Department. Telemed. J. E Health 2019, 25, 1207–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutledge, T.; Atkinson, J.H.; Holloway, R.; Chircop-Rollick, T.; D’Andrea, J.; Garfin, S.R.; Patel, S.; Penzien, D.B.; Wallace, M.; Weickgenant, A.L.; et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Nurse-Delivered Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Versus Supportive Psychotherapy Telehealth Interventions for Chronic Back Pain. J. Pain 2018, 19, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, J.; Atkinson, J.H.; Chircop-Rollick, T.; D’Andrea, J.; Garfin, S.; Patel, S.; Penzien, D.B.; Wallace, M.; Weickgenant, A.L.; Slater, M.; et al. Telehealth Therapy Effects of Nurses and Mental Health Professionals From 2 Randomized Controlled Trials for Chronic Back Pain. Clin. J. Pain 2019, 35, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suso-Ribera, C.; Castilla, D.; Zaragoza, I.; Mesas, A.; Server, A.; Medel, J.; Garcia-Palacios, A. Telemonitoring in Chronic Pain Management Using Smartphone Apps: A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Usual Assessment against App-Based Monitoring with and without Clinical Alarms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masiero, M.; Filipponi, C.; Fragale, E.; Pizzoli, S.F.M.; Munzone, E.; Milani, A.; Guido, L.; Guardamagna, V.; Marceglia, S.; Prandin, R.; et al. Support for Chronic Pain Management for Breast Cancer Survivors Through Novel Digital Health Ecosystems: Pilot Usability Study of the PainRELife Mobile App. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e51021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krkoska, P.; Vlazna, D.; Sladeckova, M.; Minarikova, J.; Barusova, T.; Batalik, L.; Dosbaba, F.; Vohanka, S.; Adamova, B. Adherence and Effect of Home-Based Rehabilitation with Telemonitoring Support in Patients with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccleston, C.; Blyth, F.M.; Dear, B.F.; Fisher, E.A.; Keefe, F.J.; Lynch, M.E.; Palermo, T.M.; Reid, M.C.; Williams, A.C.C. Managing patients with chronic pain during the COVID-19 outbreak: Considerations for the rapid introduction of remotely supported (eHealth) pain management services. Pain 2020, 161, 889–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghai, B.; Malhotra, N.; Bajwa, S.J.S. Telemedicine for chronic pain management during COVID-19 pandemic. Indian. J. Anaesth. 2020, 64, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanthanna, H.; Strand, N.H.; Provenzano, D.A.; Lobo, C.A.; Eldabe, S.; Bhatia, A.; Wegener, J.; Curtis, K.; Cohen, S.P.; Narouze, S. Caring for patients with pain during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consensus recommendations from an international expert panel. Anaesthesia 2020, 75, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes, E.B.; Santos Garcia, J.B.; de Macedo Antunes, J.; Daher, D.V.; Seixas, F.L.; Muniz Ferrari, M.F. Chronic Pain Management during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2021, 22, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Gutierrez, C.; Gil-Garcia, E.; Rivera-Sequeiros, A.; Lopez-Millan, J.M. Effectiveness of telemedicine psychoeducational interventions for adults with non-oncological chronic disease: A systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 1267–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner-Nix, J.; Barbati, J.; Grummitt, J.; Pukal, S.; Raponi Newton, R. Exploring the Effectiveness of a Mindfulness-Based Chronic Pain Management Course Delivered Simultaneously to On-Site and Off-Site Patients Using Telemedicine. Mindfulness 2012, 5, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, E.; Rosser, B.A.; Eccleston, C. e-Health and chronic pain management: Current status and developments. Pain 2010, 151, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokolo Anthony, J. Use of Telemedicine and Virtual Care for Remote Treatment in Response to COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Med. Syst. 2020, 44, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parretti, C.; La Regina, M.; Tortu, C.; Candido, G.; Tartaglia, R. Telemedicine in Italy, the starting point. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2023, 18, 949–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, L.; Marzorati, C.; Grasso, R.; Ferrucci, R.; Priori, A.; Mameli, F.; Ruggiero, F.; Pravettoni, G. Home-Based Treatment for Chronic Pain Combining Neuromodulation, Computer-Assisted Training, and Telemonitoring in Patients with Breast Cancer: Protocol for a Rehabilitative Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e49508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, S.; Rosafio, C.; Antodaro, F.; Argentiero, A.; Bassi, M.; Becherucci, P.; Bonsanto, F.; Cagliero, A.; Cannata, G.; Capello, F.; et al. Use of Telemedicine Healthcare Systems in Children and Adolescents with Chronic Disease or in Transition Stages of Life: Consensus Document of the Italian Society of Telemedicine (SIT), of the Italian Society of Preventive and Social Pediatrics (SIPPS), of the Italian Society of Pediatric Primary Care (SICuPP), of the Italian Federation of Pediatric Doctors (FIMP) and of the Syndicate of Family Pediatrician Doctors (SIMPeF). J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | ||

| Number of participants | 100 | 62 | 38 |

| Median | 65 | 64 | 66 |

| IQR | 13.75 | 16.75 | 10 |

| 25th percentile | 60.5 | 58 | 62.25 |

| 50th percentile | 65 | 64 | 66 |

| 75th percentile | 74.25 | 74.75 | 72.25 |

| Minimum | 24 | 40 | 24 |

| Maximum | 93 | 93 | 82 |

| Skewness | −0.513 | −0.026 | −1.496 |

| Std. error of skewness | 0.241 | 0.304 | 0.383 |

| Kurtosis | 0.977 | −0.291 | 4.204 |

| Std. error of Kurtosis | 0.478 | 0.599 | 0.75 |

| Shapiro–Wilk | 0.974 | 0.984 | 0.89 |

| p-value of Shapiro–Wilk | 0.045 | 0.576 | 0.001 |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Neuropathic pain | 54 (54%) | 36 (58.064%) | 18 (47.36850) |

| Complex chronic pain | 32 (32%) | 17 (27.419%) | 15 (83.333%) |

| Oncologic/neoplastic pain | 11 (11%) | 7 (11.290%) | 4 (10.526%) |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Hypertension | 30 (30%) | 24(38.710%) | 6 (15.789%) |

| Diabetes | 10 (10%) | 7 (11.290%) | 3 (7.894%) |

| Treatment | |||

| Buprenorphine | 90 (90%) | 58 (93.548%) | 32 (84.211%) |

| Surgery | 18 (18%) | 11 (17.742%) | 7 (18.421%) |

| T-Stat | Df | Wi | Wj | p | pBonf | pHolm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRS Baseline | NRS 1 month | 8.081 | 297 | 395 | 258.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| NRS 3 months | 11.78 | 297 | 395 | 196 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| NRS 6 months | 14.474 | 297 | 395 | 150.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| NRS 1 month | NRS 3 months | 3.7 | 297 | 258.5 | 196 | < 0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| NRS 6 months | 6.393 | 297 | 258.5 | 150.5 | < 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| NRS 3 months | NRS 6 months | 2.694 | 297 | 196 | 150.5 | 0.007 | 0.045 | 0.007 |

| T-Stat | Df | Wi | Wj | p | pBonf | pHolm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPI WP baseline | BPI WP 1 month | 11.092 | 297 | 399.000 | 226.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| BPI WP 3 months | 13.849 | 297 | 399.000 | 183.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| BPI WP 6 months | 13.272 | 297 | 399.000 | 192.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| BPI WP 1 month | BPI WP 3 months | 2.757 | 297 | 226.000 | 183.000 | 0.006 | 0.037 | 0.019 |

| BPI WP 6 months | 2.180 | 297 | 226.000 | 192.000 | 0.030 | 0.180 | 0.060 | |

| BPI WP 3 months | BPI WP 6 months | 0.577 | 297 | 183.000 | 192.000 | 0.564 | 1.000 | 0.564 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amato, F.; Monaco, M.C.; Ceniti, S. Transforming Chronic Pain Care Through Telemedicine: An Italian Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1626. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21121626

Amato F, Monaco MC, Ceniti S. Transforming Chronic Pain Care Through Telemedicine: An Italian Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(12):1626. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21121626

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmato, Francesco, Maria Carmela Monaco, and Silvia Ceniti. 2024. "Transforming Chronic Pain Care Through Telemedicine: An Italian Perspective" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 12: 1626. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21121626

APA StyleAmato, F., Monaco, M. C., & Ceniti, S. (2024). Transforming Chronic Pain Care Through Telemedicine: An Italian Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(12), 1626. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21121626