Awareness and Knowledge of Developmental Coordination Disorder Among Healthcare Professionals in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics/Sociodemographic

3.2. Participants Familiarity with Neurodevelopmental Disorders

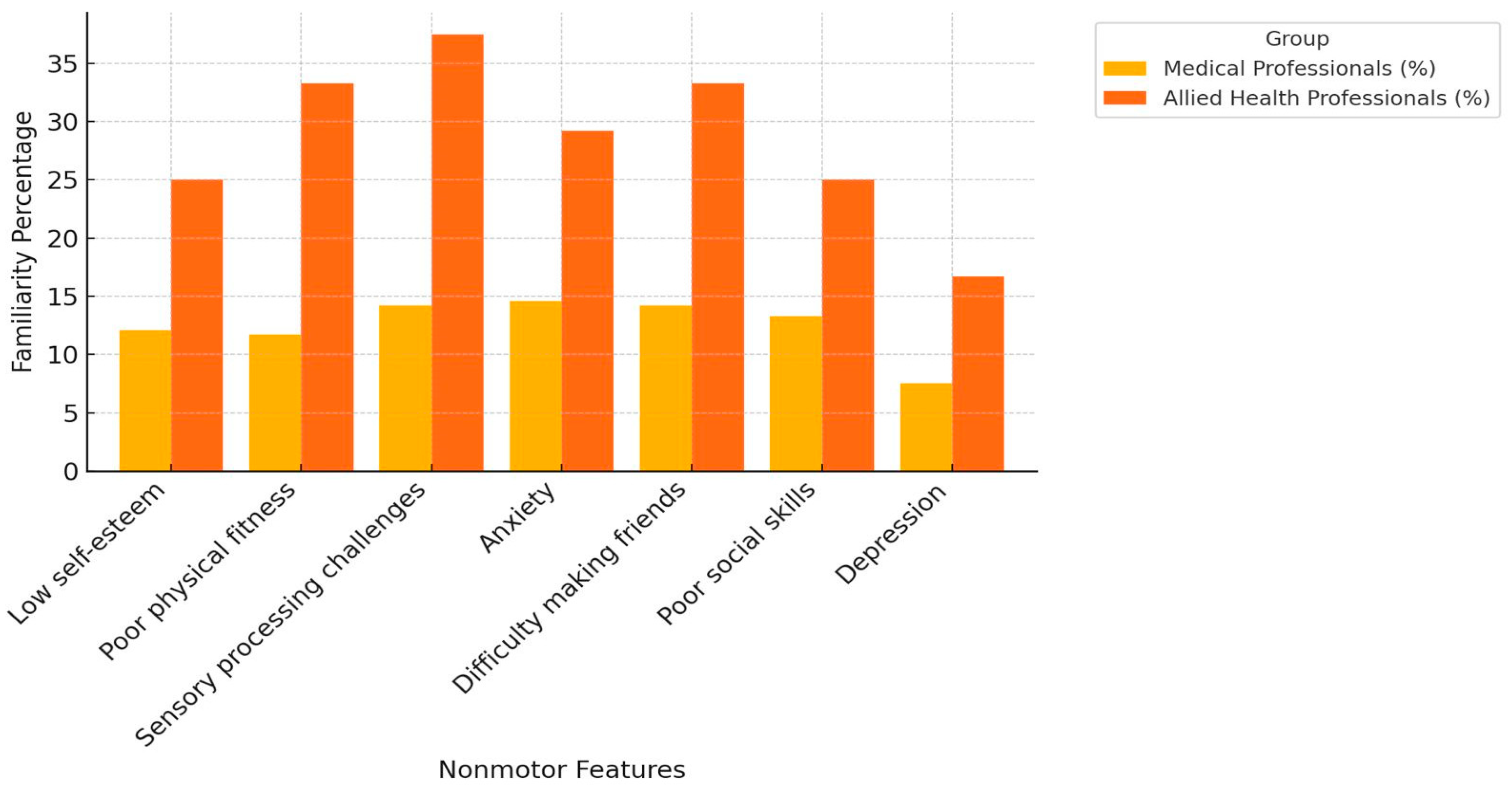

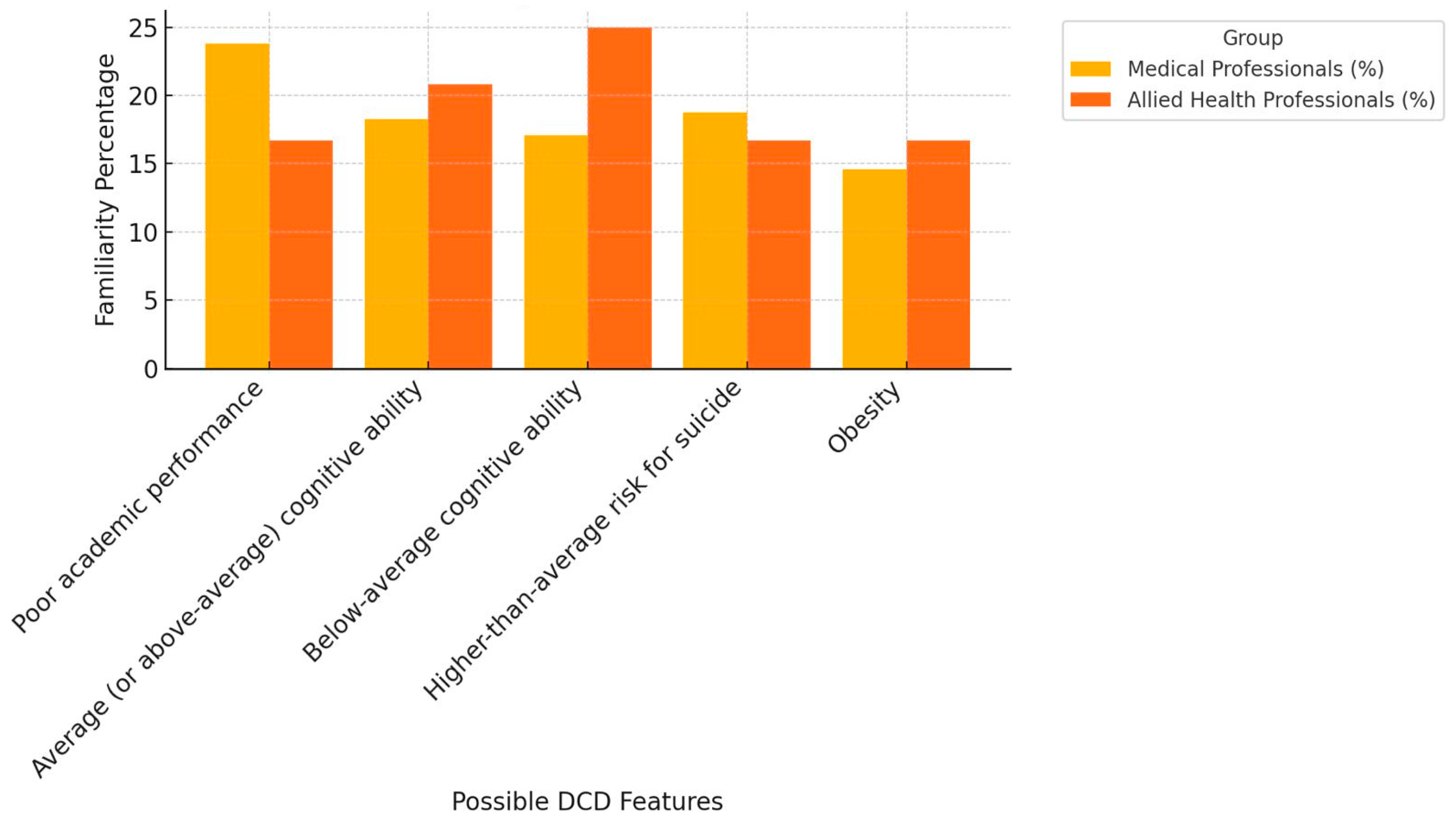

3.3. Participants Familiarity with DCD Features

3.4. Participants Views on DCD Management Strategies

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with International Findings

4.2. Medical Professionals vs. Allied Health Professionals

4.3. Knowledge of DCD’s Symptoms

4.4. Knowledge Deficits

4.5. Recommendations to Raise Awareness

4.6. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (DSM-5), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, R.; Barnett, A.L.; Cairney, J.; Green, D.; Kirby, A.; Polatajko, H.; Rosenblum, S.; Smits-Engelsman, B.; Sugden, D.; Wilson, P.; et al. International clinical practice recommendations on the definition, diagnosis, assessment, intervention, and psychosocial aspects of developmental coordination disorder. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2019, 61, 242–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- British Association of Community Child Health (Child Development and Disability Group). Standards for Child Development Services: A Guide to Commissioners and Providers; Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Karkling, M.; Paul, A.; Zwicker, J.G. Occupational therapists’ awareness of guidelines for assessment and diagnosis of developmental coordination disorder: Mesure selon laquelle les ergothérapeutes connaissent les lignes directrices relatives à l’évaluation et au diagnostic du trouble du développement de la coordination. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 84, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, J.; Appleton, J.; Appleton, R. Dyspraxia or developmental coordination disorder? Unravelling the enigma. Arch. Dis. Child. 2007, 92, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, R. Developmental dyspraxia: Or just plain clumsy? Early Years 1991, 12, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.L.; Hill, E.L. Anxiety profiles in children with and without developmental coordination disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel-Yeger, B.; Engel, A. Emotional distress and quality of life among adults with developmental coordination disorder during COVID-19. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2023, 86, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, R.; Smits-Engelsman, B.; Polatajko, H.; Wilson, P. European Academy for Childhood Disability. European Academy for Childhood Disability (EACD): Recommendations on the definition, diagnosis and intervention of developmental coordination disorder (long version). Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2012, 54, 54–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.N.; Neil, K.; Kamps, P.H.; Babcock, S. Awareness and knowledge of developmental co-ordination disorder among physicians, teachers and parents. Child. Care. Health Dev. 2013, 39, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghadier, M.; Alhusayni, A.I. Evaluating the Efficacy of Gross-Motor-Based Interventions for Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, A.G.; Sullivan, K.M.; Soe, M.M. OpenEpi: Open-Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health. Available online: www.OpenEpi.com (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Hunt, J.; Zwicker, J.G.; Godecke, E.; Raynor, A. Awareness and knowledge of developmental coordination disorder: A survey of caregivers, teachers, allied health professionals and medical professionals in Australia. Child Care Health Dev. 2021, 47, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meachon, E.J.; Melching, H.; Alpers, G.W. The overlooked disorder: (Un)awareness of developmental coordination disorder across clinical professions. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2024, 8, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missiuna, C.; Cairney, J.; Pollock, N.; Campbell, W.; Russell, D.J.; Macdonald, K.; Schmidt, L.; Heath, N.; Veldhuizen, S.; Cousins, M. Psychological distress in children with developmental coordination disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 1198–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnon-Roy, M.; Jasmin, E.; Camden, C. Social participation of teenagers and young adults with developmental co-ordination disorder and strategies that could help them: Results from a scoping review. Child Care Health Dev. 2016, 42, 840–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwicker, J.G.; Suto, M.; Harris, S.R.; Vlasakova, N.; Missiuna, C. Developmental coordination disorder is more than a motor problem: Children describe the impact of daily struggles on their quality of life. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 81, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS Choices. Treatment—Developmental Co-Ordination Disorder (Dyspraxia) in Children. 2019. Available online: www.nhs.uk/conditions/developmental-coordination-disorder-dyspraxia/treatment/ (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Developmental Coordination Disorder|CanChild. 2000. Available online: www.canchild.ca/en/diagnoses/developmental-coordination-disorder (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Graham, I.D.; Logan, J.; Harrison, M.B.; Straus, S.E.; Tetroe, J.; Caswell, W.; Robinson, N. Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2006, 26, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Section | Questions | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic data |

| All answer options were in categorical values. |

| Professional experience |

| All answer options were in categorical values. |

| Knowledge about DCD |

| Answers: I have not heard of this condition at all, Very unfamiliar, Somewhat unfamiliar, Somewhat familiar, Very familiar. |

| Answers: Yes, No. | |

| Answers: Yes, No. | |

| Answers: Common feature of the condition, May be a feature of the condition, Not part of the condition, Unsure. | |

| Answers: Agree, Disagree, Unsure | |

| Answers: More boys than girls, More girls than boys, Equal between boys and girls, I don’t know. |

| Item | Description | Frequency | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20–30 years 31–40 years 41–50 years 51–60 years Above 60 years Total | 146 78 34 4 2 264 | 55.3% 29.5% 12.8% 1.5% 0.75% 100% |

| Gender | Female Male Total | 151 113 264 | 57.1% 42.8% 100% |

| Marital status | Single Married Divorced Widow/er Total | 129 124 10 1 264 | 48.8% 46.9% 3.7% 0.4% 100% |

| Number of children | 0 1 2 3 4 More than five Total | 160 28 32 20 14 10 264 | 60.6% 10.6% 12.1% 7.5% 5.3% 3.7% 100% |

| Nationality | Saudi Non-Saudi Total | 245 19 264 | 92.8% 7.2% 100% |

| Current profession | General practitioner Pediatrician Family physician Occupational therapist Physical therapist Nurse Surgical subspeciality Radiology Total | 87 38 45 9 15 58 7 5 264 | 32.9% 14.3% 17% 3.4% 5.7% 21.9% 2.6% 1.9% 100% |

| Years of experience | Less than 1 year 1–5 years 6–10 years 11–15 years 16–20 years More than 20 years Total | 43 126 44 29 12 8 264 | 16.2% 47.7% 16.6% 10.9% 4.5% 3% 100% |

| Employment type | Full time Part time Total | 235 29 264 | 89% 11% 100% |

| Highest degree/qualification | Diploma Bachelor Master Specialist/Specialty Certification Consultant/Fellowship PhD Total | 6 170 14 41 26 7 264 | 2.3% 64.3% 5.3% 15.5% 9.8% 2.6% 100% |

| Age groups covered in practice | Infants (0–1 years) Toddlers (1–3 years) Preschool-aged children (4–5 years) School-aged children (6–14 years) Adolescents (15–18 years) Adults Elderly | 96 113 122 128 102 117 73 | 36.3% 42.8% 46.2% 48.4% 38.6% 44.3% 27.6% |

| Pediatric patients seen per week | None 1–10 11–20 21–30 31–40 More than 40 Total | 64 18 70 51 35 26 264 | 24.2% 6.8% 26.5% 19.3% 13.2% 9.8% 100% |

| Patients with developmental motor delays seen in the past six months | None 1–10 11–20 21–30 31–40 More than 40 Total | 116 85 32 15 4 12 264 | 43.9% 32.1% 12.1% 5.7% 1.5% 4.5% 100% |

| Previous assignment of the DCD diagnosis | Yes No Total | 56 208 264 | 21.2% 78.8% 100% |

| Condition * | Total n = 264 | MP n = 240 | AHP n = 40 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Global developmental delay | 97 | 36.7% | 87 | 36.2% | 10 | 41.6% |

| Speech and language disorders | 125 | 74.3% | 115 | 48% | 10 | 41.6% |

| Intellectual disability | 121 | 45.8% | 111 | 46.2% | 10 | 41.6% |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 127 | 48.1% | 117 | 49% | 10 | 41.6% |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 139 | 52.6% | 128 | 53.3% | 11 | 45.8% |

| Developmental coordination disorder | 91 | 34.4% | 80 | 33.3% | 11 | 45.8% |

| Tourette’s disorder | 104 | 39.3% | 97 | 40.4% | 7 | 29.1% |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 128 | 48.4% | 121 | 50.4% | 7 | 29.1% |

| Conduct disorder | 84 | 31.8% | 77 | 32% | 7 | 29.1% |

| Childhood-onset fluency disorder (Stuttering) | 96 | 36.3% | 85 | 35.4% | 11 | 45.8% |

| Clumsy child syndrome | 59 | 22.3% | 51 | 21.2% | 8 | 33.3% |

| Dyspraxia | 81 | 30.6% | 70 | 29.1% | 11 | 45.8% |

| Asperger’s syndrome | 74 | 28% | 65 | 27% | 9 | 37.5% |

| Spina bifida | 119 | 45% | 107 | 44.5% | 12 | 50% |

| Dyslexia | 95 | 35.9% | 83 | 34.5% | 12 | 50% |

| Oppositional defiance disorder | 77 | 29.1% | 69 | 28.7% | 8 | 33.3% |

| Motor learning disability | 91 | 34.4% | 80 | 33.3% | 11 | 45.8% |

| Chromosomal disorders | 123 | 46.5% | 112 | 46.6% | 11 | 45.8% |

| Learning disability | 125 | 47.3% | 116 | 48.3% | 9 | 37.5% |

| Statement | Number of Agree Responses (n = 264) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Further research is needed on DCD. | 120 | 45.45% |

| I feel I need more education/information regarding the condition of DCD. | 112 | 42.4% |

| I believe there are significant benefits from an accurate diagnosis of DCD being given early. | 119 | 45.1% |

| Learning that the estimated incidence of DCD is between 5% and 6% in children would surprise me. | 91 | 34.5% |

| The DSM-5 contains enough information about DCD for an accurate diagnosis to be made. | 60 | 22.7% |

| DCD would be relatively easy to identify. | 50 | 18.9% |

| There are adequate support professionals for children with DCD in the school system. | 52 | 19.7% |

| Accurate diagnoses and classifications are critical for educators to know how to help children with DCD. | 100 | 37.9% |

| I believe educators should play a role in identifying early warning signs that can help to diagnose DCD. | 117 | 44.3% |

| There are too many conditions for educators to keep up with. | 89 | 33.7% |

| Currently, the education system would not be able to adequately support children with DCD given the lack of knowledge and perceptions about the condition. | 95 | 36% |

| I believe there are children in the school system labeled as lazy or defiant that, in fact, have gross and/or fine motor skill impairments. | 105 | 39.8% |

| There are adequate support professionals for children with DCD in the school system. | 60 | 22.7% |

| Item # | Saudi Arabia (Eastern Region)—MP (%) | Saudi Arabia (Eastern Region)—AHP (%) | Australian—MP (%) [13] | Australian—AHP (%) [13] | Canada, UK, US Study—Physicians (%) [10] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common motor features of DCD | |||||

| Motor learning difficulties | 20.4 | 45.8 | 52 | 85 | 79 |

| Difficulty printing and/or writing | 17.9 | 41.7 | 56 | 75 | 77 |

| Gross motor and/or fine motor skills delay | 18.3 | 62.5 | 52 | 81 | 70 |

| Mean knowledge score | 18.87 | 50 | 53.3 | 80.3 | 75.3 |

| Common nonmotor features of DCD | |||||

| Low self-esteem | 12.1 | 25 | 33 | 50 | 59 |

| Poor physical fitness | 11.7 | 33.3 | 22 | 38 | 49 |

| Sensory processing challenges | 14.2 | 37.5 | 19 | 22 | 42 |

| Anxiety | 14.6 | 29.2 | 22 | 23 | 40 |

| Difficulty making friends | 14.2 | 33.3 | 15 | 13 | 40 |

| Poor social skills | 13.3 | 25 | 13 | 11 | 37 |

| Depression | 7.5 | 16.7 | 7 | 7 | 28 |

| Mean knowledge score | 12.9 | 28.5 | 18.71 | 27.71 | 42.14 |

| May be a feature of DCD | |||||

| Poor academic performance | 23.8 | 16.7 | 19 | 55 | 41 |

| Average cognitive ability | 18.3 | 20.8 | 11 | 36 | 48 |

| Below-average cognitive ability | 17.1 | 25 | 4 | 41 | 16 |

| Higher risk for suicide | 18.75 | 16.7 | 4 | 49 | 20 |

| Obesity | 14.6 | 16.7 | 4 | 44 | 17 |

| Mean knowledge score | 18.11 | 19.18 | 8.4 | 45 | 28.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Ahmari, A.A.; Alshabaan, A.A.; Almeer, A.A.; AlKhater, M.N.; Al-Ibrahim, M.A.; Altuwal, H.H.; Al-Dajani, A.A.; Alqahtani, S.A.; Al-Omari, M.A.; Almutairi, A.K.; et al. Awareness and Knowledge of Developmental Coordination Disorder Among Healthcare Professionals in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21121602

Al-Ahmari AA, Alshabaan AA, Almeer AA, AlKhater MN, Al-Ibrahim MA, Altuwal HH, Al-Dajani AA, Alqahtani SA, Al-Omari MA, Almutairi AK, et al. Awareness and Knowledge of Developmental Coordination Disorder Among Healthcare Professionals in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(12):1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21121602

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Ahmari, Abdulaziz A., Abdullah A. Alshabaan, Ali A. Almeer, Mohammed N. AlKhater, Mohammed A. Al-Ibrahim, Hassan H. Altuwal, Alaeddin A. Al-Dajani, Saleh A. Alqahtani, Mohammed A. Al-Omari, Abdullah K. Almutairi, and et al. 2024. "Awareness and Knowledge of Developmental Coordination Disorder Among Healthcare Professionals in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 12: 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21121602

APA StyleAl-Ahmari, A. A., Alshabaan, A. A., Almeer, A. A., AlKhater, M. N., Al-Ibrahim, M. A., Altuwal, H. H., Al-Dajani, A. A., Alqahtani, S. A., Al-Omari, M. A., Almutairi, A. K., & AlQurashi, F. O. (2024). Awareness and Knowledge of Developmental Coordination Disorder Among Healthcare Professionals in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(12), 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21121602