Abstract

This systematic review identifies and describes the use of the Expert Recommendation for Implementing Change (ERIC) concepts and strategies using public health approaches to drowning prevention interventions as a case study. International calls for action have identified the need to better understand the implementation of drowning prevention interventions so that intervention design and implementation is improved. In high-income countries (HICs), interventions are sophisticated but still little is known or written about their implementation. The review was registered on PROSPERO (number CRD42022347789) and followed the PRISMA guidelines. Eight databases were searched. Articles were assessed using the Public Health Ontario Meta-tool for quality appraisal of public health evidence. Forty-nine articles were included. Where ERIC strategies were reported, the focus was on evaluative and iterative strategies, developing partnerships and engaging the target group. The review identified few articles that discussed intervention development and implementation sufficiently for strategies to be replicated. Findings will inform further research into the use and measurement of implementation strategies by practitioners and researchers undertaking work in drowning prevention in HICs and supports a call to action for better documentation of implementation in public health interventions.

1. Introduction

The generation and use of knowledge is critical for evidence-informed public health practice. There is recognition of the need to address the challenges that hinder closing the “know–do” gap in public health implementation [1,2]. Implementation science seeks to address these barriers using methods and strategies that facilitate the uptake of evidence-based practice and research into regular use by practitioners and policymakers [3]. There are several considerations inherent in this sentiment. When interventions are assessed as being effective, if others do not utilise them, they will not become widely accepted [4]. Intervention implementation requires active consideration to ensure that programs are deployed with and into communities more efficiently and effectively.

A range of frameworks and tools have been developed to guide implementation, for example, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [5] and Theoretical Domains Framework [6]. Common to these frameworks is the use of domains and constructs to explain and measure implementation and describe the interplay of the intervention content and context to effect behaviour change. However, there are few frameworks specific to public health [1,7], despite growing interest in the use and impact of implementation science for public health interventions [7,8,9,10]. The Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project identified nine concepts and 73 strategies that aid in the development [11] of implementation strategies and can serve as a tool to assess the strategies used in implementation. This tool was initially designed for a clinical setting [11,12]; it has been refined and used to reflect public health practice within a community setting [7]. There are examples of implementation science being used in some health and community settings [7,11,13] across mental health [4,11,12,14,15] and substance use [16]. However, in other public health areas, such as drowning prevention, which is the case study for this review, the application of implementation science is limited [7].

Drowning is a leading cause of unintentional injury [17,18], resulting in over 2.5 million deaths worldwide over the last decade [19]. Drowning is a complex global public health issue with different drivers across low-, middle- and high-income contexts [20,21,22,23]. In HICs, drowning events tend to occur during recreational activities [17,24] around the water and around the home [25]. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), there is a higher prevalence of children drowning close to home due to issues of supervision, barriers to water sources and water safety skills, while older children and adults drown when undertaking work or during travel on water [21,26]. While there is evidence of community-led interventions [22,23] and institutional guidance around effective strategies to reduce drowning [27], the literature also highlights gaps in the quality, consistency and reporting of programs [22,23,28]. There are also differences in the number of drowning prevention-related peer-reviewed publications published [22,23] and the types of interventions [29] relevant for LMICs compared to HICs. Of the limited published interventions from LMICs, most were delivered by agencies without the capacity to include large-scale evaluation or knowledge translation [17,23]; thus, implementation in the two settings (HIC and LMIC) is not directly applicable [29].

Consequently, there have been international calls for action to establish processes to better understand the implementation of drowning prevention interventions in community settings [19,26,30] and several resources have been developed to aid in the implementation of drowning prevention interventions [31,32,33]. However, these resources have concentrated on the activities of interventions (e.g., the WHO implementation guide focusses on ten evidence-based interventions and strategies [31]) rather than the process of implementation and tend to be conducted in LMICs. In HICs, there is a growing focus on the use of evidence to strengthen the design, delivery and evaluation of interventions [23], with calls for practitioners and researchers to learn from each other [26]. Recent advancements in the publication of more sophisticated approaches to the development of drowning prevention interventions [23] lend themselves to further exploration of context of intervention implementation.

This systematic review aims to identify drowning prevention studies undertaken in HICs as a public health case study of implementation science and describe and assess the use of implementation science ERIC concepts and strategies. The review asks:

- What are the implementation strategies used in drowning prevention interventions in high-income countries and how are they described?

- What are the gaps in the use and reporting of implementation strategies in drowning prevention interventions in high-income countries?

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [34] and registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (ID CRD42022347789) [35]. The search strategy for included articles and the PRISMA checklists for abstracts and manuscripts were completed (Supplementary Tables S1, S2 and S3, respectively).

2.1. Criteria for Inclusion

Included articles were primary studies, addressed drowning prevention interventions in HICs, were written in English and were published between 2002 and 2022 (see Table 1). HICs are defined as economies with a gross national income (GNI) of USD12,696 or more per capita [36]. Exclusion criteria included articles that focus on clinical aspects of drowning events; specific target groups or locations not relevant to the wider population (i.e., those with water phobia, working on specific construction sites); simulation studies (i.e., studies of cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or rescue delivery in specific settings) or other injury prevention (i.e., not solely drowning prevention). Articles addressing the development of recommendations and/or guidelines, where no intervention was described, were also excluded.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.2. Search Strategy

In consultation with the university health sciences faculty librarian, the initial literature search strategy was developed using medical subject heading (MESH) and text words related to implementation and drowning prevention. Once an initial Medline search was completed, the strategy was adapted to the subject headings of seven additional databases (see Supplementary Table S1 for full search strategy): PubMed, PsycINFO, ProQuest, Scopus, Web of Science, Global health and SPORTDiscus.

2.3. Screening and Quality Appraisal

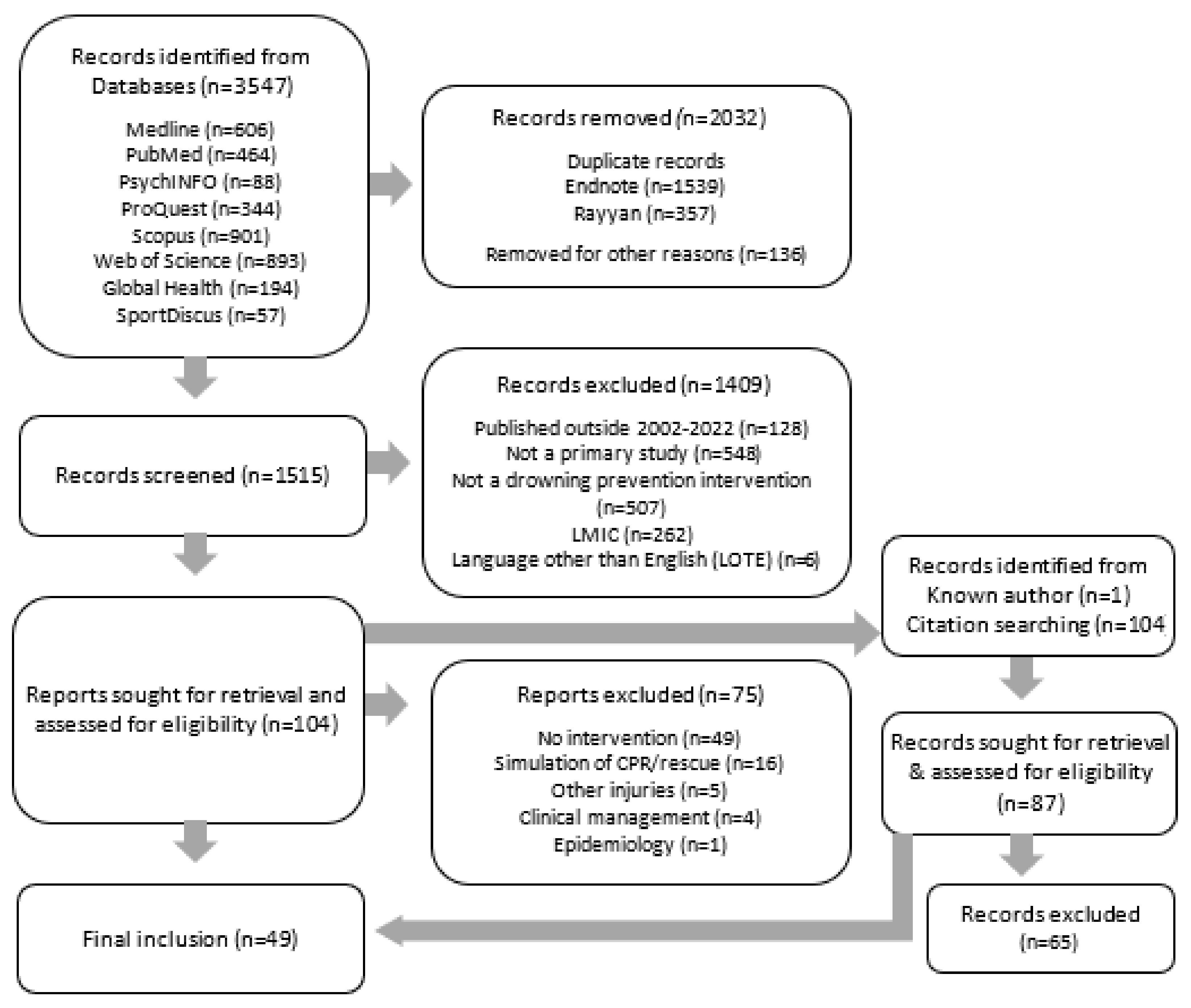

The initial database search identified 3547 articles. All citations from the initial search were imported into Endnote 20 [37] referencing management software. Using the Endnote and Rayyan software [38] “find duplicates” tool, 1539 articles were removed. Two reviewers (MDB and BR) individually screened the identified articles by title and abstract using Rayyan [38] to determine the relevance of the remaining articles (n = 1515). Articles were categorized as “possibly relevant”, “maybe” (where the reviewer was unsure if the article met the criteria) and “excluded”. The systematic review PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [34] is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for review of implementation concepts and strategies identified in drowning prevention literature from 2002–2022.

Articles identified as “maybe” during the title and abstract search were re-classified through discussion amongst two research team members (MDB and BR) and. where there was disagreement, with a third member of the team (JL). The full text articles identified as “possibly relevant” were retrieved and assessed by one reviewer (MDB) using a standardized exclusion list. A second researcher (BR) randomly cross-checked 10% of articles to identify any selection anomalies. Any full-text articles classified as “maybe” were resolved with a co-author (GC). To ensure coverage, the reference lists of “possible inclusion” articles (n = 104) were hand-searched for any articles not previously identified; 22 further articles were identified (see Figure 1).

All included articles (n = 49) were assessed for quality using the Public Health Ontario Meta-tool for quality appraisal of public health evidence (PHO META QAT) [39] by one reviewer (BR). Another reviewer (MDB) randomly cross-checked 10% of the appraisals to ensure accuracy. Articles were analysed and scored using four domains (relevance, reliability, validity and applicability) containing nine categories [40] and were scored as met the criteria = 2, not sure/unclear = 1 and did not meet the criteria = 0. As in previous reviews [23], articles were categorized on their summed score, where ≤9 = low quality (n = 11), 10–14 = medium quality (n = 17) and 15–18 = high quality (n = 21). All 49 articles met the criteria for inclusion based on the quality appraisal.

2.4. Outcome Measure (Implementation)

Included drowning prevention intervention articles were assessed for inclusion using the refined Expert Recommendations of Implementing Change (ERIC) project concepts and strategies for use in community settings [7,11,41]. Refinement was made to the criteria by the first author (MDB). Changes are described in Supplementary Table S4. In summary, refinements included terminology changes to reflect drowning prevention “interventions” in place of “clinical innovations” [11], “target group and support networks” in place of “patient/consumers and families” [11] or “priority populations” [7], and “providers” in place of “clinicians” [11]. These modifications were verified with a practitioner with over 10 years’ experience in the drowning prevention sector. The final list of nine ERIC concepts and 73 strategies are described in Table 2. The nine concepts include: c1 use evaluative and iterative strategies, c2 provide iterative assistance, c3 adapt and tailor context, c4 develop partner relationships, c5 train and educate stakeholders, c6 support providers, c7 engage target group, c8 financial strategies and c9 change infrastructure.

Table 2.

ERIC strategy definitions.

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

The following data were extracted from the drowning prevention articles:

- Author; year; aim; location; sample (n); recruitment; response rate.

- Intervention: level (i.e., who the intervention involved—individual, group, population); type (behavioral—actions taken by individuals to prevent drowning [42]; socio-ecological—social, physical, policy or environmental; or mixed (behavioral and socio-ecological) [43]); activity; duration; use of theory (theory); formative research.

- Evaluation: design; measures; human research ethical approval (HREC); findings.

- Implementation: level (i.e., systemic, organizational, provider, target group); concepts [41]; strategies [7,11,44] (used and recommended).

3. Results

A total of 49 peer-reviewed articles were included [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93]. Table 3 presents the extracted data.

Table 3.

General study characteristics, intervention, evaluation and implementation (n = 49).

3.1. Overview of Case Studies (Intervention and Evaluation)

Twenty articles were from Australia (n = 20, 40.8%), 19 (38.8%) from the United States of America (USA), and the remaining articles were from Canada (n = 3, 6.1%), New Zealand (n = 3, 6.1%), the United Kingdom (n = 1, 2.0%), Greece (n = 1, 2.0%), Uruguay (n = 1, 2.0%) and Italy (n = 1, 2.0%). Most articles (n = 42, 85.7%) were published from 2012 onwards, with half of those (n = 22) published in the last five years (2017–2022). Ethical approval was reported in 32 articles (65.3%), with the remaining not recorded (n = 16, 32.6%) or identified as not required (n = 1, 2.0%) due to the clinical environment of the data collection. Participation ranged in size, with samples taken from clinical settings (n = 7) such as patients’ attending physicians’ rooms to state-wide initiatives (n = 14,842) and ranged in duration from one-week to 20-year interventions.

Most interventions (n = 48, 98.0%) were delivered at the population or group level, with only one at the individual level. Intervention types were mostly behavioral (n = 31, 63.3%), with the remainder identified as a combination of both behavioral and socio-ecological (n = 10, 20.4%) or socio-ecological only (n = 8, 16.3%). Study activities included pool-based swimming or water safety lessons (n = 12, 24.5%), training for parents (n = 12, 24.5%), beach safety education (n = 5, 10.2%), cardiopulmonary resuscitation first aid or bystander training (n = 5, 10.2%). Other activities included lifejacket use (n = 4, 8.2%) and pool fencing (n = 2, 4.1%). Twenty-seven articles did not identify the use of theory (55.1%). The uses of theory most identified were the Health Belief Model (n = 6) and Theory of Planned Behaviour (n = 4). The remaining articles identified educational, behavioral and social marketing theories.

The evaluation design methodology included observational studies (n = 7, 14.2%), quantitative (n = 27, 55.1%), qualitative (n = 1, 2.0%) and mixed methods (n = 9, 18.4%). In addition, four articles (8.1%) included process evaluation only and one educational article did not discuss evaluation. The most frequently recorded measures included knowledge (n = 20), attitudes and beliefs (n = 14), risk perception (n = 11), water-based activities undertaken (n = 10), behavioral intent (n = 9) and intervention awareness (n = 9). In observational studies, the main measure recorded was swim skills (n = 6) or personal flotation device use (n = 2).

3.2. Implementation Key Concepts and Strategies

Table 4 summarizes the identified ERIC concepts and strategies. Throughout the tables and text, the concepts and strategies have been identified in brackets, where “cX” identifies the concept and the underscore number “_XX” identifies the strategy. All nine concepts were identified across the 49 articles, with developing partner relationships (c4) (n = 32, 65.3%), evaluative and iterative strategies (c1) (n = 29, 59.2%) and engaging with the target group (c7) (n = 22, 44.9%) the most common concepts. Four articles reported the concept change infrastructure (c9) (8.2%). One included study [76] did not identify any implementation strategies.

Table 4.

Summary of implementation concepts and strategies identified in the drowning prevention literature.

Forty-three ERIC strategies (58.9%) were identified. The most frequently identified strategies were develop academic partnerships (c4_04) (n = 18, 36.7%), promote network collaboration (c4_13) (n = 14, 28.6%), intervene with the target group to enhance uptake and adherence (c7_02) (n = 14, 28.6%) and conducting local needs assessment (c1_04) (n = 11, 22.4%). Twenty-five (34.2%) ERIC strategies were identified four times or fewer (see Table 4).

Concepts and strategies identified in the intervention articles are detailed below, in order of frequency.

3.2.1. Developing Partner Relationships (c4)

Partnerships were developed with a range of groups, including academic institutions (n = 18) [46,50,51,52,53,54,60,61,64,67,75,77,78,85,86,87,88,89], community groups (n = 5) [66,73,83,86,89], local councils (n = 2) [72,91] and public health organizations (n = 1) [83]. For example, Mitchell and Haddrill [73] worked closely with local groups to implement the SafeWaters campaign for the Chinese community in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Quan and colleagues worked with the Vietnamese community in Washington, USA to develop and evaluate an intervention to combat a spate of local drownings in the community. Van Weerdenburg and colleagues [49] identified the importance of local council support for implementing pool fencing inspection programs.

Develop Academic Partnerships (c4_04)

Partnerships with university academics (n = 18) were identified as human research ethics committee (HREC) approvals and research–practitioner collaborations. More than half the examples of developing academic partnerships (55.6%) involved the use of university or research group ethics boards [46,51,53,75,77,85,86,87,88,89], whilst almost two-thirds of articles (n = 31, 63.3%) indicated they had received ethical approval. HREC approval within the strategy develop academic partnerships were recorded if it was clear where the ethics approval was obtained, with an approval number included. For example, an intervention designed by Koon and colleagues [64] was undertaken by the Lake Macquarie City Council and the University of New South Wales Beach Safety Research Group, obtained HREC approval and aided in developing tools for the intervention. In another study, Hamilton and colleagues [61] reported the development of resources in partnership with university academics.

Promote Network Collaboration (c4_13)

Network collaborations involved identifying and expanding existing networks within and outside the lead organization to promote information sharing, collaborative problem solving and a shared vision/goal for implementing the intervention [11]. The collaboration took the form of involvement of organization staff with expertise from a variety of backgrounds [48,79,84,90,92], working with not-for profit organizations [59,83], development of multi-sectorial partnerships [49,83,89], expert input into the campaign [73,94] and the development of evaluation tools [59,90]. For example, Quan, Shepard and Bennett [83] worked with community groups, the parks department and public health organizations to limit barriers to uptake by the Vietnamese community by reinstating lifeguards at beach and lake sites, providing low-cost swim lessons and the development of translated material for services. In another study, Sandomierski and colleagues [85] reported that linking programs with a broader drowning prevention initiative may have created more opportunities for collaboration and consistency of messaging regarding child water safety.

3.2.2. Engage the Target Group (c7)

Target group engagement included improving participation in an intervention by using existing networks and events [52,57,58,64,67,74,81]. For example, Franklin and colleagues [57] used schools to engage children, and Giresek [58] used pre-natal classes to engage new parents. Moran and Stanley [74] provided poolside education for parents while their children undertook swimming lessons. Mass media were used to disseminate information, such as updated boating safety regulations, to the general community in the study by Bugeja and colleagues [52].

Intervene with the Target Group to Enhance Uptake and Adherence (c7_02)

In the study by Petrass and colleagues [82], the community provided feedback on the timing of interventions, whilst Beattie, Shaw and Larson [50] received feedback on their intervention location, and Yusef and colleagues [93] reviewed evaluation tools used by pediatricians to educate parents.

3.2.3. Evaluative and Iterative Strategies (c1)

Several (n = 6) drowning prevention pilot study interventions were identified [50,67,74,84,90,92]. The ongoing examination and refinement of implementation strategies by the intervention teams were also common in four studies [70,80,82,93]. Koon and colleagues [64] piloted school-based intervention materials based on lifeguards’ expertise in delivering an intervention and used focus groups with high school children to refine the program content and delivery [64].

Conducting Local Needs Assessment (c1_04)

Several articles (n = 11) described the use of local needs assessments to understand the target group. This included the use of focus groups (n = 6) [64,73,83,84,86,89], identification of barriers by experts (n = 2) via existing knowledge [75,92], review of the literature (n = 2) [77,81] and drowning trend data [95]. Morrongiello and colleagues [77] described using a review of the literature, local drowning trends and the National Water Safety Framework to inform the content for an awareness-raising program for parents on supervision of children around the water. Intervention locations were also purposively selected by need based on the formative findings [77]. In other articles, Mitchell and Haddrill [73] and Quan and colleagues [83] conducted focus groups with the local Chinese and Vietnamese–American communities, respectively. Savage and Franklin [86] conducted focus groups with culturally and linguistically diverse people regarding barriers to participating in water safety programs.

3.2.4. Adapting and Tailoring the Context (c3)

Examples of ways in which interventions were adapted to suit local conditions included adaption to the availability of swimming facilities [80] and the swim ability of the target group [48,80,81]. The needs of the target group [79] and providers [64] and the accessibility and relevance of the interventions for specific communities [73,90] were considered. For example, Olaisen and colleagues [79] offered a variety of enrolment options for swimming lessons, providing between one and three swimming lessons. Petrass and Blitvich [81] tested perceived swim ability against actual swim ability in the first four lessons of their water-based intervention and then introduced specific skills relevant to the participants.

3.2.5. Train and Educate Stakeholders (c5)

Stakeholder training and education were included in initial drowning prevention sessions (conduct educational meetings (c5_01)) to ensure key community leaders [66] and staff [69,79,82,91] understood the intervention before it was delivered to the wider community, as well as ongoing implementation meetings (create a learning collaborative (c5_04)) to ensure providers were learning from each other [93]. Other strategies included the development and distribution of resources for providers to support implementation [67,82,93] and the use of [45,79] and recommendations for [73,75] dynamic training delivery methods. For example, Love-Smith and colleagues [67] developed a presentation script and talking points for presenters at educational sessions, while Petrass and colleagues [82] developed lesson plans and other resources for providers to ensure the consistency of content delivery and lesson progression. The strategy to provide ongoing consultation (C5_08) was not identified in any articles.

3.2.6. Provide Interactive Assistance (c2) and Support Providers (c6)

Only one strategy, facilitation (c2_02), was identified [45,48,75,80,86]. Examples of facilitation included interactive problem solving undertaken with the target group, their support network and/or providers. For example, Olivar [80] identified that the swim teacher’s role was to identify issues in swimming skills with teaching styles focused on learner-centered problem solving with the participants. Teachers were considered active participants in the learning process and prioritized creating a supportive environment and opportunities were offered for participants to complete tasks at their own readiness and competency levels. The strategies providing supervision (c2_04), remind providers (C6_04) and revising professional roles (c6_05) were not identified in the articles.

3.2.7. Financial Strategies (c8) and Change Infrastructure (c9)

The concepts addressing financial strategies (c8) and change infrastructure (c9) were the least-frequently identified in the articles, with neither concept including strategies identified more than five times (key strategies).

Fund and contract for the evidence-informed intervention (c8_05) was identified in two articles. Franklin and colleagues [57] identified the Swim and Survive Program as being subsidized by the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), and the Water Safety in the Bush project was funded by community organizations [50].

Van Weerdenburg, Mitchell and Wallner’s study [91] into pool fence compliance with the state’s Swimming Pools Act of 1992 in Australia described financial strategies (c8) and change infrastructure (c9). Changes were made to liability laws and enforcement (c9_03) by granting authority to councils to access properties to inspect pools. Recommendations were made to correct or make explicit inconsistencies between the Act and other regulations and related Australian standards (change liability laws or enforcement (c8_02) and introduce a provision within the Act for inspection fees to assist with the cost of managing compliance, record systems and inspections (place interventions on a fee-for-service list (c8_07)).

4. Discussion

This review sought to identify, describe and categorize the drowning prevention implementation strategies used in HIC settings. The findings were mapped to ERIC implementation concepts and strategies [7,11,41] to capture the breadth of implementation of drowning prevention interventions in HICs published in the peer-reviewed literature. It included 49 articles about drowning prevention interventions in HICs published between 2002 and 2022. The review found that articles were mostly from Australia and the USA, varying by sample and intervention level, with most interventions delivered at the group (e.g., school classroom, expectant parents) and population levels. Interventions most frequently used behavioral [42] strategies or a combination of behavioral and socio-ecological strategies [43]. Interventions covered the drowning prevention activities identified by the International Life Saving Federation [27], including environmental modifications, promoting swimming and lifesaving skills, cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills, surveillance and supervision. Evaluation designs were mostly quantitative, with several mixed-method and observational studies also included. All nine ERIC concepts and forty-two ERIC strategies were identified within the intervention studies. Fifteen strategies across six concepts were identified five times or more (key strategies).

4.1. Understanding the Use of Implementation Strategies in Drowning Prevention Interventions

Three concepts were consistently identified: developing partner relationships, engage target group and iterative and evaluative strategies. This indicates that “developing relationships, engaging with the target group and checking what works as programs progress” are at the forefront for researchers and practitioners when reporting on drowning prevention activities. These strategies are also core competencies for those working in public health, health promotion [42,96], injury prevention [97] and advocacy [98], indicating that a complementary public health and injury prevention lens is used to frame drowning prevention interventions in HICs. This aligns with the way drowning prevention is framed as a public health issue by the World Health Organization [30,31,32,33,99]. The development of skills related to relationship building, target-group engagement and advocacy are a priority for the public health workforce, as central capabilities highlighted in the Global Charter for Public Health [100] and the Council of Academic Public Health Institutions Australasia (CAPHIA) Master of Public Health competencies [101].

Our review highlights that the fundamental principles of planning and evaluating programs (i.e., the concepts of formative research and stakeholder and target group engagement) are clearly identifiable components of the peer-reviewed drowning prevention literature in HICs. However, while these concepts were consistently identified, there was not always sufficient detail [102] available to support those implementing future interventions to replicate or decide [103] to use similar strategies and limited examples of implementation strategies described in the context of recommendations for similar programs. For example, Stempski and colleagues [89] stated that partner organizations identified a representative (project champion) who shared survey learnings at bimonthly meeting to help foster change among others as a collaborative and iterative process of improvement highlighting success and barriers, but did not explain how project champions were identified or engaged. To build practitioner implementation capacity, understanding what was carried out may not always be enough [104]. The implementation strategies used need to be compared and/or assessed against current practice to improve uptake [7].

This review highlights a need for the processes related to the transformation and adaptation of implementation strategies used in practice to be better understood [104]. One way to do this may be through the use of causal loop diagrams and system modelling [103] in drowning prevention interventions to better explore the interactions influencing decision making [104] and allow for an exploration of factors, such as organizational and evaluation capacity [102], affecting implementation decision making [7]. Alternatively, exploration of the gaps and factors affecting the uptake of implementation strategies [105] with practitioners and researchers would also be beneficial.

Developing partner relationships was the most frequently identified ERIC concept; developing academic partnerships was the most cited ERIC strategy. It is posited that the requirement for HREC approval when publishing in peer-reviewed journals may mean the impact of academic partnerships in the implementation of drowning prevention interventions in HICs is over-estimated in the literature. Research has found that practitioners often feel intimidated by the term “ethics”, equating oversight processes to research, and feel that the process of gaining ethics approval has limited benefit to service delivery [106,107]. Other identified barriers to the use of institutional ethical approval include organizational capacity, competing priorities and access [106]. These perceptions have the consequent effect of limiting the integration of ethical oversight into policy and practice [108] and further, reducing the likelihood of practitioners and policy makers publishing in the peer-reviewed literature, as ethical oversight is a requirement for most journals [109]. Being explicit about the ethical foundations of public health interventions are important to ensure they are informed by evidence, do what was intended, avoid iatrogenic effects and follow agreed guidelines and principles related to the ethical conduct of human research [107].

Drowning prevention interventions are designed and delivered by water safety practitioners, who have varying capacity and skills [97,110] in designing, implementing and evaluating programs. For example, practitioners in the water safety space are often lifeguards, fishers and swim instructors [110] working in complex settings and impacted by system factors that affect the intervention, provider and community [111,112], with variations in organizational capacity, staff skills and technical components [113]. Thus, consistent with findings in community health promotion more broadly [106], it is likely that drowning prevention practitioners may feel ethical approval has a limited benefit to service delivery. Enhancing knowledge of ethical practice and streamlining access to ethical oversight by making research–practice partnerships more common may facilitate greater participation in formal ethical oversight processes and greater contribution to the peer-reviewed literature by a broader range of practitioners.

Community and academic partnerships have the greatest potential to improve the successful implementation of evidence-informed practice [114]. Community and academic partnerships ensure that decision-making processes and subsequent interventions are feasible and sustainable [115,116] by utilizing a shared vision and impact benchmarking. To ensure that researchers consider interesting, important research questions and use effective methodology [114], practitioners develop evaluation practices and skills [117] and knowledge translation [106] within the industry occurs in a timely manner, there is a need to further develop strategies that truly enhance research–practice partnerships.

Overall, the review identified a lack of consistent language used to describe implementation of the interventions. For example, in the five articles [45,48,75,80,86] where examples of facilitation (c2_02) (a process of interactive problem solving and support that occurs in the context of a recognised need for improvement and a supportive interpersonal relationship [11]) were identified, the terms facilitation or problem solving were not used. Instead, examples described how the participants “engaged in tasks that targeted their underlying deficit” [45], described how “factors such as personal instructor qualities, program structure and support and day-to-day interactions with students were important” [48] and iterated that “time was allowed for the pool-side parents to seek advice from the instructor” [75]. Similar issues of inconsistent terminology have been identified by other authors when reviewing the obesity literature [118] and implementation guidelines more broadly [119]. More consistent use of implementation terminology in the drowning prevention literature would be useful to ensure that the implementation strategies are easier to identify and better understood. This could be achieved with the development and use of a framework guide for the implementation of drowning prevention interventions for use by practitioners, researchers, funding bodies and decision makers.

4.2. Gaps in the Use and Reporting of Implementation Strategies

Approximately 40% of the ERIC implementation strategies (n = 30) were not identified in included articles. This result is consistent with observational and qualitative research into the use of ERIC strategies in general practice across the USA [120]. We speculate that some non-identified ERIC strategies are likely to be undertaken but are limited in detail or not formally captured and reported in the peer-reviewed literature. This is highlighted by the limited reporting of informing local opinion leaders (c4_08) (n = 2) and identifying and preparing champions (c4_06) (n = 1) and no cases of identifying early adopters (c4_07), despite community groups identified as partners and collaborators in multiple articles [48,49,73,83,84] and included in pre-delivery training to provider and community members [66]. The limited detail included in the literature, whereby the definitions for the ERIC strategies have not been met (e.g., identify and prepare champions), has been noted by other studies discussing the use of implementation strategies in community settings [7] and may also be the case for other strategies such as remind providers (c6_04) and provide ongoing consultation (C5_08).

The concepts of financial strategies and change infrastructure did not include any key strategies and were largely absent from the reviewed literature. Drowning prevention interventions tend to focus on education, the physical environment or community and social context, with financial strategies (c8) mainly utilized by interventions undertaken by local councils (in the case of pool fencing requirements) [91] and involving service delivery (i.e., access to pool facilities [83] or subsidized swim lesson participation [57]). In the case of financial strategies, it may be that the use of public health [26,31,99] rather than implementation science [7] to frame drowning prevention means that the economic impacts on behaviour change [121] and financial indicators of organizational capacity [122] have been somewhat overlooked [121].

4.3. What Was Learnt?

In general, the current use and reporting of implementation strategies in the published literature highlights that various implementation strategies are likely over-reported (reported in the literature at a higher proportion than they are used), under-reported (used more often than they are reported in the literature) and in some cases, overlooked (neither likely used nor reported in the literature). The consequence of over-reporting implementation strategies is a false sense of what is occurring in the field whilst under-reporting means interventions are difficult to replicate. Those publishing drowning prevention interventions in the peer-reviewed literature could refocus efforts towards intervention implementation. Further exploration of the use and adaptation of existing resources and systems (e.g., databases, provider training) to support providers to deliver interventions could go some way to support and strengthen the implementation of drowning prevention interventions.

5. Strengths and Limitations

Whilst the call for methodologically sound reviews of implementation in public health interventions has been made [7,119], this review is the first to report on ERIC implementation concepts and strategies using the HIC drowning prevention literature as a case study. Strengths include searching eight databases, a purposefully broad scope (i.e., did not include “interventions” in the search terms), following procedures for previously published systematic reviews [22,23,24] and the use of a public health-specific quality-appraisal tool (Meta QAT) [39]. Several limitations included the restriction to English language and the exclusion of the grey literature. The grey literature may have yielded a wider range of interventions; however, technical reports [123], annual reports [124] and websites [125] were more likely to describe interventions for funders and the general community and were deemed unlikely to describe implementation strategies. An over-representation of from Australia and the USA may reflect that drowning prevention efforts have attracted funding and resources, which has allowed for a research–practice nexus to be established and afforded peer-reviewed publications. In contrast, there were few non-English articles, suggesting drowning prevention may be a lower priority for research funding in some countries and the opportunity to publish becomes limited. As with other reviews of public health intervention implementation [118], the lack of consistent terminology to describe implementation strategies in the drowning prevention literature may mean some articles were missed. Despite these limitations, this study begins a discussion of the use of implementation science in drowning prevention interventions and adds to the small but growing evidence base on how drowning prevention interventions are implemented.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this systematic review serve as a starting point for further exploration of the implementation strategies used in drowning prevention interventions. The review highlights the need for more detailed, accurate reporting of the implementation of interventions to aid in the replication and refinement of evidence-informed interventions. The use and reporting of implementation strategies in published, peer-reviewed drowning prevention interventions in HICs is varied and lacks depth, making interventions difficult to replicate or making it difficult to know which implementation strategies add to the success of an intervention and why. The concepts of evaluative and iterative strategies and adapting to the context are relatively well-developed. However, there is a paucity of evidence on other concepts such as how providers and stakeholders are supported, trained and educated.

Potential improvements that may support better capture of the implementation strategies include increased articles in the peer-reviewed literature that describe the process of program planning, implementation and evaluation and the use of consistent drowning prevention implementation language. Supporting practitioners to identify and apply implementation strategies in their day-to-day work can facilitate real-world enhancements in public health action for drowning prevention in HICs.

Future endeavors include an exploration of intervention implementation with drowning prevention practitioners and researchers, which will allow for the gaps identified in this review to be further understood. We anticipate that this will go some way to better describe the use of implementation strategies, which has theoretical, methodological and practical implications, thus strengthening the implementation of evidence-informed interventions in HICs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph21010045/s1, Supplementary Table S1: Systematic review search strategy (October 2022); Supplementary Table S2: PRISMA checklist abstract; Supplementary Table S3: PRISMA checklist manuscript; Supplementary Table S4: Refinement of ERIC strategies.

Author Contributions

M.D.B. conceived the study design with input from J.E.L., G.C. and J.J. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by M.D.B. and B.R.; J.E.L. and G.C. acted as third reviewers where there were discrepancies. Additional data analysis was performed by M.D.B. The draft manuscript was written by M.D.B., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge the financial support from a Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship provided to Malena Della Bona for this PhD project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Rachel Murray for aiding in the modification of ERIC concepts and strategies as they relate to drowning prevention interventions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Estabrooks, P.A.; Brownson, R.C.; Pronk, N.P. Dissemination and implementation science for public health professionals: An overview and call to action. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2018, 15, E162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escoffery, C.; Lebow-Skelley, E.; Udelson, H.; Böing, E.A.; Wood, R.; Fernandez, M.E.; Mullen, P.D. A scoping study of frameworks for adapting public health evidence-based interventions. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinson, C.A.; Stamatakis, K.A.; Kerner, J.F. Dissemination and implementation research in community and public health settings. In Dissemination and Implementation Research om Health: Translating Science to Practice; Brownson, R.C., Colditz, G.A., Proctor, E., Eds.; Oxford Scholarship Online: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M.S.; Kirchner, J. Implementation science: What is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Res. 2020, 283, 112376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhal, E.; Arena, A.; Sockalingam, S.; Mohri, L.; Crawford, A. Adapting the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to Create Organizational Readiness and Implementation Tools for Project ECHO. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2018, 38, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, L.; Francis, J.; Islam, R.; O’Connor, D.; Patey, A.; Ivers, N.; Foy, R.; Duncan, E.M.; Colquhoun, H.; Grimshaw, J.M.; et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balis, L.E.; Houghtaling, B.; Harden, S.M. Using implementation strategies in community settings: An introduction to the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) compilation and future directions. Transl. Behav. Med. 2022, 12, 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownson, R.C.; Fielding, J.E.; Green, L.W. Building Capacity for Evidence-Based Public Health: Reconciling the Pulls of Practice and the Push of Research. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2018, 39, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, R.C.; Cooper, B.R.; Stirman, S.W. The Sustainability of Evidence-Based Interventions and Practices in Public Health and Health Care. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2018, 39, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, R.C.; Lee, M.; Brotzman, L.E.; Wolfenden, L.; Nathan, N.; Wainberg, M.L. What Is Dissemination and Implementation Science?: An Introduction and Opportunities to Advance Behavioral Medicine and Public Health Globally. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2020, 27, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, B.J.; Waltz, T.J.; Chinman, M.J.; Damschroder, L.J.; Smith, J.L.; Matthieu, M.M.; Proctor, E.K.; Kirchner, J.E. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, B.J.; McMillen, J.C.; Proctor, E.K.; Carpenter, C.R.; Griffey, R.T.; Bunger, A.C.; Glass, J.E.; York, J.L. A Compilation of Strategies for Implementing Clinical Innovations in Health and Mental Health. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2012, 69, 123–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, D.C.; Durlak, J.A.; Wandersman, A. The quality implementation framework: A synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 50, 462–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, M.S.; Rusch, D.; Mehta, T.G.; Lakind, D. Future directions for Dissemination and Implementation Science: Aligning Ecological Theory and Public Health to close the research to practice gap. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2016, 45, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchner, J.E.; Ritchie, M.J.; Pitcock, J.A.; Parker, L.E.; Curran, G.M.; Fortney, J.C. Outcomes of a Partnered Facilitation Strategy to Implement Primary Care–Mental Health. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinman, M.; Imm, P.; Wandersman, A. Getting to Outcomes&Trade: 2004: Promoting Accountability through Methods and Tools for Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Scarr, J.-P.; Jagnoor, J. Mapping trends in drowning research: A bibliometric analysis 1995–2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beeck, E.F.; Branche, C.M.; Szpilman, D.; Modell, J.H.; Bierens, J.J.L.M. A new definition of drowning: Towards documentation and prevention of a global public health problem. Bull. World Health Organ. 2005, 83, 853–856. [Google Scholar]

- United Nation General Assembly. Global Drowning Prevention: Resolution A/RES/75/273; United Nation General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, R.; Peden, A.E.; Hamilton, E.B.; Bisignano, C.; Castle, C.D.; Dingels, Z.V.; Hay, S.I.; Liu, Z.; Mokdad, A.H.; Roberts, N.L.S.; et al. The burden of unintentional drowning: Global, regional and national estimates of mortality from the Global Burden of Disease 2017 Study. Inj. Prev. 2020, 26, i83–i95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, M.D.; Richards, D.B.; Reske-Nielsen, C.; Saghafi, O.; Morse, E.A.; Carey, R.; Jacquet, G.A. The epidemiology of drowning in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, J.E.; Crawford, G.; Leaversuch, F.; Nimmo, L.; McCausland, K.; Jancey, J. A review of drowning prevention interventions for children and young people in high, low and middle income countries. J. Community Health 2016, 41, 424–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, J.E.; Gray, C.; Della Bona, M.; D’Orazio, N.; Crawford, G. A Review of Interventions for Drowning Prevention Among Adults. J. Community Health 2023, 48, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, J.E.; Crawford, G.; Portsmouth, L.; Jancey, J.; Leaversuch, F.; Nimmo, L.; Hunt, K. Recreational drowning prevention interventions for adults, 1990–2012: A review. J. Community Health 2015, 40, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaida, F.J.; Gaida, J.E. Infant and toddler drowning in Australia: Patterns, risk factors and prevention recommendations. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2016, 52, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meddings, D.R.; Scarr, J.-P.; Larson, K.; Vaughan, J.; Krug, E.G. Drowning prevention: Turning the tide on a leading killer. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e692–e695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Life Saving Federation (ILSF). Drowning Prevention Strategies: A Framework to Reduce Drowning Deaths in the Aquatic Environment for Nations/Regions Engaged in Lifesaving; International Life Saving Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Peden, A.E.; Franklin, R.C.; Leggat, P.A. Fatal river drowning: The identification of research gaps through a systematic literature review. Inj. Prev. 2016, 22, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyder, A.A.; Alonge, O.; He, S.; Wadhwaniya, S.; Rahman, F.; El Arifeen, S. A framework for addressing implementation gap in global drowning prevention interventions: Experiences from Bangladesh. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2014, 32, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Assembly. Resolution WHA 76.18 Accelerating action on global drowning prevention. In Proceedings of the 76th World Health Assembly, Geneva, Switzerland, 29 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Preventing Drowning: An Implementation Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on the Prevention of Drowning through Provision of Day-Care and Basic Swimming and Water Safety Skills; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Preventing Drowning: Practical Guidance for the Provision of Day-Care, Basic Swimming and Water Skills, and Safe Rescure and Resuscitation Training; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, A.; Clarke, M.; Dooley, G.; Ghersi, D.; Moher, D.; Petticrew, M.; Stewart, L. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: An international prospective register of systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2012, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- The Endnote Team. Endnote; Endnote 20; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario); Rosells, L.C.; Pach, B.; Morgan, S.; Bowman, C. Meta-Tool for Quality Appraisal of Public Health Evidence: PHO MetaQAT; Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rosella, L.; Bowman, C.; Pach, B.; Morgan, S.; Fitzpatrick, T.; Goel, V. The development and validation of a meta-tool for quality appraisal of public health evidence: Meta Quality Appraisal Tool (MetaQAT). Public Health 2016, 136, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltz, T.J.; Powell, B.J.; Matthieu, M.M.; Damschroder, L.J.; Chinman, M.J.; Smith, J.L.; Proctor, E.K.; Kirchner, J.E. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D.; Muscat, D.M. Health Promotion Glossary 2021. Health Promot. Int. 2021, 36, 1578–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokols, D. Translating Social Ecological Theory into Guidelines for Community Health Promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996, 10, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, C.R.; Lyon, A.R.; Locke, J.; Waltz, T.; Powell, B.J. Adapting a Compilation of Implementation Strategies to Advance School-Based Implementation Research and Practice. Prev. Sci. 2019, 20, 914–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaniz, M.L.; Rosenberg, S.S.; Beard, N.R.; Rosario, E.R. The Effectiveness of Aquatic Group Therapy for Improving Water Safety and Social Interactions in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Program. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 4006–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araiza-Alba, P.; Keane, T.; Matthews, B.; Simpson, K.; Strugnell, G.; Chen, W.S.; Kaufman, J. The potential of 360-degree virtual reality videos to teach water-safety skills to children. Comput. Educ. 2021, 163, 104096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.E.E.; Giles, A.R.; Marianayagam, J.; Toth, K.M. Kids don’t float…and their parents don’t either: Using a family-centered approach in Alaska’s kids don’t float program. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2020, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beale, A.K. Fulfilling the Promise of Making a Difference: Creating Guards of Life with TPSR. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2012, 6, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Beale-Tawfeeq, A.K.; Anderson, A.; Ramos, W.D. A cause to action: Learning to develop a culturally responsive/relevant approach to 21st century water safety messaging through collaborative partnerships. (Special Issue: Diversity in aquatics). Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2018, 11, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Beattie, N.; Shaw, P.; Larson, A. Water safety in the bush: Strategies for addressing training needs in remote areas. Rural Remote Health 2008, 8, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brander, R.W.; Williamson, A.; Dunn, N.; Hatfield, J.; Sherker, S.; Hayen, A. Evaluating the effectiveness of a science-based community beach safety intervention: The Science of the Surf (SOS) presentation. Cont. Shelf Res. 2022, 241, 104722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugeja, L.; Cassell, E.; Brodie, L.R.; Walter, S.J. Effectiveness of the 2005 compulsory personal flotation device (PFD) wearing regulations in reducing drowning deaths among recreational boaters in Victoria, Australia. Inj. Prev. 2014, 20, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassell, E.; Newstead, S. Did compulsory wear regulations increase personal flotation device (PFD) use by boaters in small power recreational vessels? A before-after observational study conducted in Victoria, Australia. Inj. Prev. 2015, 21, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casten, M.; Crawford, G.; Jancey, J.; Bona, M.D.; French, S.; Nimmo, L.; Leavy, J.E. ‘Keep watch’ around water: Short-term impact of a Western Australian population-wide television commercial. J. Public Health 2022, 30, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.; Quan, L.; Bennett, E.; Kernic, M.A.; Ebel, B.E. Informing policy on open water drowning prevention: An observational survey of life jacket use in Washington state. Inj. Prev. 2014, 20, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, A.B.; Sleap, M. “Swim for Health”: Program evaluation of a multiagency aquatic activity intervention in the united kingdom. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2013, 7, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Franklin, R.C.; Peden, A.E.; Hodges, S.; Lloyd, N.; Larsen, P.; O’Connor, C.; Scarr, J. Learning to swim: What influences success? Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2015, 9, 220–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girasek, D.C. Evaluation of a brief intervention designed to increase CPR training among pregnant pool owners. Health Educ. Res. 2011, 26, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, T.J.; Castor, T.; Karmakar, M.; Blavos, A.; Dagenhard, P.; Domigan, J.; Sweeney, E.; Diehr, A.; Kucharewski, R. A Social Marketing Intervention to Prevent Drowning among Inner-City Youth. Health Promot. Pract. 2018, 19, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Keech, J.J.; Willcox-Pidgeon, S.; Peden, A.E. An evaluation of a video-based intervention targeting alcohol consumption during aquatic activities. Aust. J. Psychol. 2022, 74, 2029221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Peden, A.E.; Keech, J.J.; Hagger, M.S. Changing people’s attitudes and beliefs toward driving through floodwaters: Evaluation of a video infographic. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 53, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, J.; Williamson, A.; Sherker, S.; Brander, R.; Hayen, A. Development and evaluation of an intervention to reduce rip current related beach drowning. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2012, 46, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houser, C.; Trimble, S.; Brander, R.; Brewster, B.C.; Dusek, G.; Jones, D.; Kuhn, J. Public perceptions of a rip current hazard education program: “Break the Grip of the Rip!”. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 17, 1003–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koon, W.; Brander, R.W.; Alonzo, D.; Peden, A.E. Lessons learned from co-designing a high school beach safety education program with lifeguards and students. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2022, 34, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koon, W.A.; Bennett, E.; Stempski, S.; Blitvich, J. Water Safety Education Programs in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Seattle Communities: Program Design and Pilot Evaluation. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2021, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, K.A.; Duzinski, S.V.; Wheeler, T.; Yuma-Guerrero, P.J.; Johnson, K.M.; Maxson, R.T.; Schlechter, R. Teaching safety at a summer camp: Evaluation of a water safety curriculum in an urban community setting. Health Promot. Pract. 2012, 13, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love-Smith, R.; Koon, W.A.; Tabios, L.; Bartell, S.M. Eyes save lives water safety program for parents and caregivers: Program design and pilot evaluation from Southern California. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2021, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, B.; Andronaco, R.; Adams, A. Warning signs at beaches: Do they work? Saf. Sci. 2014, 62, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, B.L.; Franklin, R.C. Examination of a pilot intervention program to change parent supervision behaviour at Australian public swimming pools. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2018, 29, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallin, T.; Morgan, M.; Camp, E.A.; Yusuf, S. A Pilot Study on Water Safety Education of Providers and Caregivers in Outpatient Pediatric Clinical Settings to Increase Drowning Prevention Knowledge. Clin. Pediatr. 2020, 59, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarrison, R.; Ren, D.; Woomer, G.R.; Cassidy, B. Evaluation of a Self-Instructional CPR Program for Parents with Children Enrolled in Community Swim Lessons. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2017, 31, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Haddrill, K. Swimming pool fencing in New South Wales: Who is checking compliance? Health Promot. J. Aust. 2004, 15, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Haddrill, K. Working in partnership with the Chinese community in NSW to develop appropriate strategies to target water safety. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2004, 15, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, K.; Stanley, T. Toddler drowning prevention: Teaching parents about water safety in conjunction with their child’s in-water lessons. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2006, 13, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, K.; Stanley, T.; Rutherford, A. Toddler drowning prevention: Teaching parents about child CPR in conjunction with their child’s in-water lessons. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2012, 6, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moran, K.; Webber, J.; Stanley, T. The 4Rs of Aquatic Rescue: Educating the public about safety and risks of bystander rescue. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2017, 24, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrongiello, B.A.; Sandomierski, M.; Schwebel, D.C.; Hagel, B. Are parents just treading water? The impact of participation in swim lessons on parents’ judgments of children’s drowning risk, swimming ability, and supervision needs. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 50, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrongiello, B.A.; Sandomierski, M.; Spence, J.R. Changes over swim lessons in parents’ perceptions of children’s supervision needs in drowning risk situations: “His swimming has improved so now he can keep himself safe”. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaisen, R.H.; Flocke, S.; Love, T. Learning to swim: Role of gender, age and practice in Latino children, ages 3–14. Inj. Prev. 2018, 24, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivar, A.I.O. Creativity, Experience, and Reflflection: One Magic Formula to Develop Preventive Water Competences. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2019, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Petrass, L.A.; Blitvich, J.D. Preventing adolescent drowning: Understanding water safety knowledge, attitudes and swimming ability. The effect of a short water safety intervention. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 70, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrass, L.A.; Simpson, K.; Blitvich, J.; Birch, R.; Matthews, B. Exploring the impact of a student-centred survival swimming programme for primary school students in Australia: The perceptions of parents, children and teachers. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2021, 27, 684–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Shephard, E.; Bennett, E. Evaluation of a Drowning Prevention Campaign in a Vietnamese American Community. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2020, 12, 4. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Rawlins, K.C. Reestablishing a Culture of Water Competency at an HBCU. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2018, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandomierski, M.C.; Morrongiello, B.A.; Colwell, S.R. SAFER Near Water: An Intervention Targeting Parent Beliefs About Children’s Water Safety. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2019, 44, 1034–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, M.A.; Franklin, R.C. Exploring the delivery of swimming and water safety teacher training to culturally and linguistically diverse communities. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2015, 9, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurati, R.; Michielon, G.; Signorini, G.; Invernizzi, P.L. Towards a Safe Aquatic Literacy: Teaching the breaststroke swimming with mobile devices’ support. A preliminary study. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2019, 19, 1999–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, N.; Mangione, T.W.; Chow, W.; Quan, L.; Bennett, E. Parental Choices of Flotation Devices for Children and Teen Swimmers and Waders: A Survey at Beaches in Washington State. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2019, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stempski, S.; Liu, L.; Grow, H.M.; Pomietto, M.; Chung, C.; Shumann, A.; Bennett, E. Everyone swims: A community partnership and policy approach to address health disparities in drowning and obesity. (Special Issue: The evidence for policy and environmental approaches to promoting health). Health Educ. Behav. 2015, 42, 106S–114S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzidis, A.; Koutroumpa, A.; Skalkidis, I.; Matzavakis, I.; Malliori, M.; Frangakis, C.E.; Discala, C.; Petridou, E.T. Water safety: Age-specific changes in knowledge and attitudes following a school-based intervention. Inj. Prev. 2007, 13, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Weerdenburg, K.; Mitchell, R.; Wallner, F. Backyard swimming pool safety inspections: A comparison of management approaches and compliance levels in three local government areas in NSW. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2006, 17, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, J.; Kanasa, H.; Pendergast, D.; Clark, K. Beach safety education for primary school children. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2017, 24, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, S.; Jones, J.L.; Camp, E.A.; McCallin, T.E. Drowning prevention counselling by paediatricians to educate caregivers on water safety. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2022, 58, 1584–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, K.; Price, S.; Keech, J.J.; Peden, A.E.; Hagger, M.S. Drivers’ experiences during floods: Investigating the psychological influences underpinning decisions to avoid driving through floodwater. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 28, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Crispin, B.; Bennett, E.; Gomez, A. Beliefs and practices to prevent drowning among Vietnamese-American adolescents and parents. Inj. Prev. 2006, 12, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Ottowa Charter for Health Promotion; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Jancey, J.; Crawford, G.; Hunt, K.; Wold, C.; Leavy, J.; Hallett, J. The injury workforce in Western Australia: Findings from a cross-sectional survey. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2020, 31, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoneham, M.; Vidler, A.; Edmunds, M. Advocacy in Action: A Toolkit for Public Health Professionals; Public Health Advocacy Institute of Western Australia: Perth, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Drowning: Preventing a Leading Killer; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Federation of Public Health Associations. The Global Charter for the Public’s Health. Available online: https://www.wfpha.org/the-global-charter-for-the-publics-health/ (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Council of Academic Public Health Institutions Australasia. Council of Academic Public Health Institutions Australasia (CAPHIA). Available online: https://caphia.com.au/ (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Lobo, R.; Petrich, M.; Burns, S.K. Supporting health promotion practitioners to undertake evaluation for program development. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobin, R.; Crawford, G.; Hallett, J.; Maycock, B.R.; Lobo, R. Critical factors that affect the functioning of a research and evaluation capacity building partnership: A causal loop diagram. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kislov, R.; Waterman, H.; Harvey, G.; Boaden, R. Rethinking capacity building for knowledge mobilisation: Developing multilevel capabilities in healthcare organizations. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.E.; ten Hoor, G.A.; van Lieshout, S.; Rodriguez, S.A.; Beidas, R.S.; Parcel, G.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Markham, C.M.; Kok, G. Implementation Mapping: Using Intervention Mapping to Develop Implementation Strategies. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackford, K.; Leavy, J.; Taylor, J.; Connor, E.; Crawford, G. Towards an ethics framework for Australian health promotion practitioners: An exploratory mixed methods study. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2022, 33, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainsbury, P. Development and oversight of ethical health promotion quality assurance and evaluation activities involving human participants. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2015, 26, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viehbeck, S.M.; Melnychuk, R.; McDougall, C.W.; Greenwood, H.; Edwards, N.C. Population and Public Health Ethics in Canada: A Snapshot of Current National Initiatives and Future Issues. Can. J. Public Health 2011, 102, 410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newson, A.J.; Lipworth, W. Why should ethics approval be required prior to publication of health promotion research? Health Promot. J. Aust. 2015, 26, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Water Safety Council. Australian Water Safety Strategy 2030; Australian Water Safety Council: Sydney, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak, J.A.; DuPre, E.P. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitson, A.; Harvey, G.; McCormack, B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: A conceptual framework. BMJ Qual. Saf. 1998, 7, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wandersman, A.; Duffy, J.; Flaspohler, P.; Noonan, R.; Lubell, K.; Stillman, L.; Blachman, M.; Dunville, R.; Saul, J. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: The Interactive Systems Framework for dissemination and implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellecchia, M.; Mandell, D.S.; Nuske, H.J.; Azad, G.; Benjamin Wolk, C.; Maddox, B.B.; Reisinger, E.M.; Skriner, L.C.; Adams, D.R.; Stewart, R.; et al. Community-academic partnerships in implementation research. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 46, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drahota, A.; Aarons, G.A.; Stahmer, A.C. Developing the Autism Model of Implementation for Autism spectrum disorder community providers: Study protocol. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.M.; Maurana, C.; Nelson, D.; Meister, T.; Young, S.N.; Lucey, P. Opening the Black Box: Conceptualizing Community Engagement From 109 Community–Academic Partnership Programs. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2016, 10, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzman, J.; Bauman, A.; Gabbe, B.J.; Rissel, C.; Shilton, T.; Smith, B.J. How practitioner, organizational and system-level factors act to influence health promotion evaluation capacity: Validation of a conceptual framework. Eval. Program Plan. 2021, 91, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, L.; Barnes, C.; Jones, J.; Finch, M.; Wyse, R.J.; Kingsland, M.; Tzelepis, F.; Grady, A.; Hodder, R.K.; Booth, D.; et al. Strategies to improve the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes within childcare services. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 1465–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, C.; McCrabb, S.; Stacey, F.; Nathan, N.; Yoong, S.L.; Grady, A.; Sutherland, R.; Hodder, R.; Innes-Hughes, C.; Davies, M.; et al. Improving implementation of school-based healthy eating and physical activity policies, practices, and programs: A systematic review. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 1365–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, C.K.; Damschroder, L.J.; Hemler, J.R.; Woodson, T.T.; Ono, S.S.; Cohen, D.J. Specifying and comparing implementation strategies across seven large implementation interventions: A practical application of theory. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlaev, I.; King, D.; Darzi, A.; Dolan, P. Changing health behaviors using financial incentives: A review from behavioral economics. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, V.; Lesneski, C.; Denison, D. Making the Case for Using Financial Indicators in Local Public Health Agencies. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidance for Creating Impactful Health Reports; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- HLB Mann Judd. A Guide to Understanding Annual Reports; Charter Practicing Accountants (CPA): Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, F.; Lindenmeyer, A.; Powell, J.; Lowe, P.; Thorogood, M. Why Are Health Care Interventions Delivered Over the Internet? A Systematic Review of the Published Literature. J. Med. Internet Res. 2006, 8, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).