The Social Ecology of Caregiving: Applying the Social–Ecological Model across the Life Course

Abstract

1. Introduction

State of Caregiving in the US

2. Public Health and the Ecological Turn

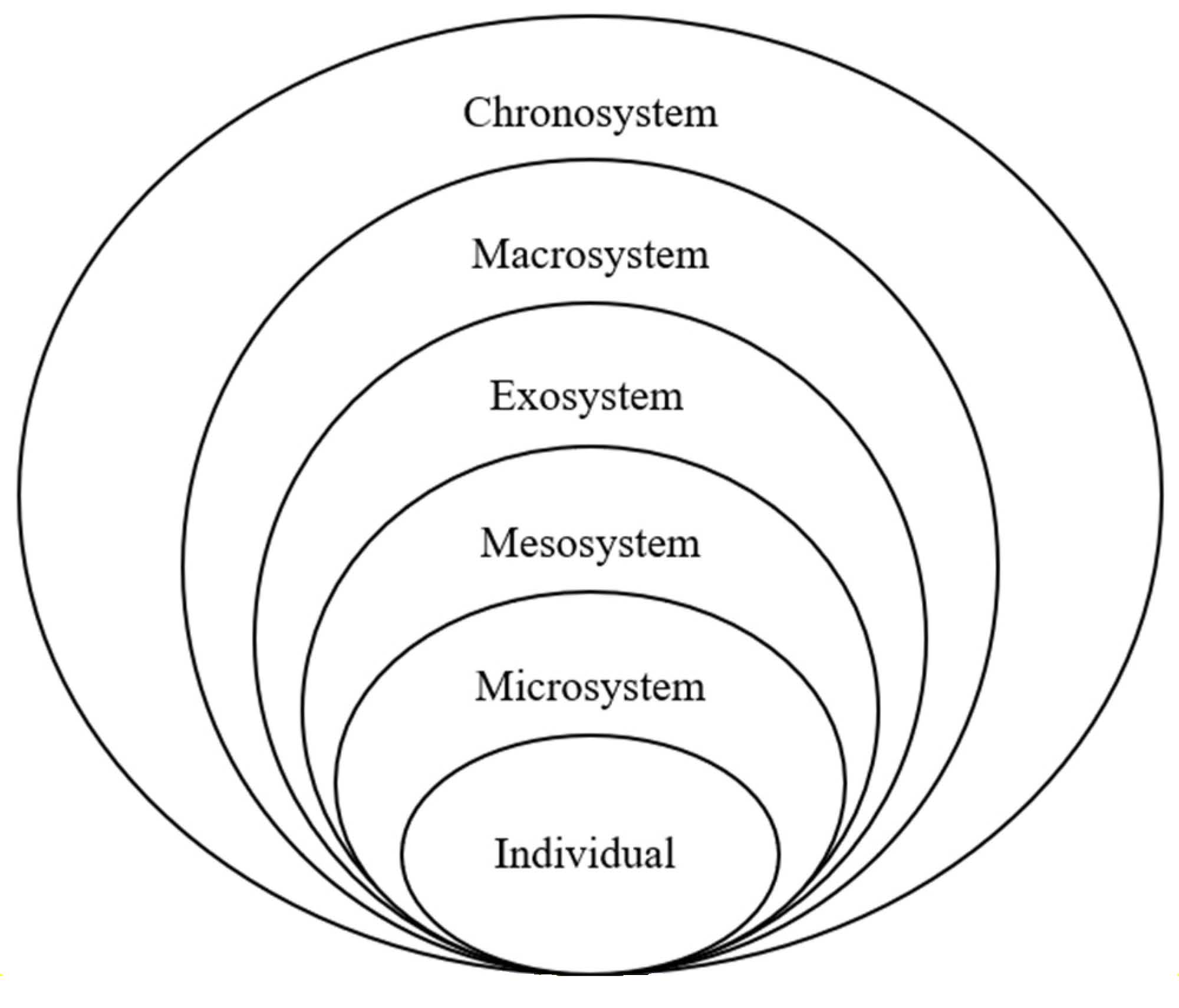

3. Ecological Systems Theory

4. Methods

Vignette-Caregiving in the Time of COVID

5. Caregiving and the Social–Ecological Model

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gibson Hunt, G.; Reinhard, S.; Greene, R.; Whiting, C.G.; Feinberg, L.F.; Choula, R.; Green, J.; Houser, A. Caregiving in the U.S. 2015 Report; National Alliance for Caregiving, AARP Public Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving. Caregiving in the United States 2020; National Alliance for Caregiving: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Eden, J. Families Caring for an Aging America; Schulz, R., Eden, J., Eds.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; ISBN-13: 978-0-309-44806-2. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For Caregivers, Family and Friends. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/aging/caregiving/index.htm (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- Parker, K.; Patten, E. The Sandwich Generation. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2013/01/30/the-sandwich-generation/ (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- Versey, H.S. Caregiving and Women’s Health: Toward an Intersectional Approach. Women’s Health Issues 2017, 27, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Reinhard, S.C.; Caldera, S.; Houser, A.; Choula, R. Valuing the Invaluable: 2023 Update: Strengthening Supports for Family Caregivers; AARP Public Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, C.; Hunt, G.G.; Halper, D.; Hart, A.Y.; Lautz, J.; Gould, D.A. Young adult caregivers: A first look at an unstudied population. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 2071–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viola, D.; Arno, P.; Siskowski, C.; Cohen, D.; Gusmano, M. The Economic Value of Youth Caregiving in the United States. Relational Child Youth Care Pract. 2012, 25, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Leu, A.; Becker, S. A cross-national and comparative classification of in-country awareness and policy responses to ‘young carers’. J. Youth Stud. 2017, 20, 750–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metlife Mature Market Institute. The MetLife Study of Caregiving Costs to Caregivers the MetLife Study of Caregiving Costs to Working Caregivers Double Jeopardy for Baby Boomers Caring for Their Parents; Mature Market Institute: Westport, CT, USA, 2011; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Eckenwiler, L.A. An ecological framework for caregiving. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 1930–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, E.E. Time to Recognize and Support Emerging Adult Caregivers in Public Health. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 1720–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plichta, S.B. Paying the hidden bill: How public health can support older adults and informal caregivers. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 1282–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talley, R.C.; Crews, J.E. Framing the Public Health of Caregiving. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, G.C.; Perrin, N.A.; Moss, H.; Laharnar, N.; Glass, N. Workplace violence against homecare workers and its relationship with workers health outcomes: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.; Thompson, S.V.; Elliot, D.L.; Hess, J.A.; Rhoten, K.L.; Parker, K.N.; Wright, R.R.; Wipfli, B.; Bettencourt, K.M.; Buckmaster, A.; et al. Safety and health support for home care workers: The COMPASS randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1823–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckrey, J.M.; Tsui, E.K.; Morrison, R.S.; Geduldig, E.T.; Stone, R.I.; Ornstein, K.A.; Federman, A.D. Beyond functional support: The range of health-related tasks performed in the home by paid caregivers in New York. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacey, C.L. The Caring Self: The Work Experiences of Home Care Aides; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 13: 9780801476990. [Google Scholar]

- Mong, S.H. Taking Care of Our Own; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 13: 9781501751455. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, M.; Van Tilburg, T.; Groenewegen, P.; Van Groenou, M.B. Linkages between informal and formal care-givers in home-care networks of frail older adults. Ageing Soc. 2016, 36, 1604–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckrey, J.M.; Geduldig, E.T.; Lindquist, L.A.; Sean Morrison, R.; Boerner, K.; Federman, A.D.; Brody, A.A. Paid caregiver communication with homebound older adults, their families, and the health careteam. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitlatch, C.J.; Judge, K.; Zarit, S.H.; Femia, E. Dyadic intervention for family caregivers and care receivers in early-stage dementia. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piercy, K.W.; Dunkley, G.J. What quality paid home care means to family caregivers. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2004, 23, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M.; Armenia, A.; Stacey, C.L. Caring on the Clock: The Complexities and Contradictions of Paid Care Work; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 9780813563114. [Google Scholar]

- Hokenstad, A.; Hart, A.Y.; Gould, D.A.; Halper, D.; Levine, C. Closing the home care case: Home health aides’ perspectives on family caregiving. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2006, 18, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Matthews, A.; Sims-Gould, J.; Tong, E. Canada’s Complex and Fractionalized Home Care Context: Perspectives of Workers, Elderly Clients, Family Carers, and Home Care Managers. Can. Rev. Soc. Policy 2012, 68/69, 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier, D.S.; Martin-Matthews, A.; Byrne, K.; Wolse, F. The space between: Using ‘relational ethics’ and ‘relational space’ to explore relationship-building between care providers and care recipients in the home space. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2015, 16, 764–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranford, C.J. Home Care Fault Lines; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN -10 1501749250. [Google Scholar]

- Delp, L.; Wallace, S.P.; Geiger-Brown, J.; Muntaner, C. Job stress and job satisfaction: Home care workers in a consumer-directed model of care. Health Serv. Res. 2010, 45, 922–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Matthews, A.; Cloutier, D.S. Household spaces of ageing: When care comes home. In Geographical Gerontology: Perspectives, Concepts, Approaches; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, C.L. Commentary: Addressing Inequities in the Era of COVID-19: The Pandemic and the Urgent Need for Critical Race Theory. Fam. Community Health 2020, 43, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, F. Youth Caregivers: Before, During, and After the Pandemic. Generations, 20, October, 2021. Available online: https://generations.asaging.org/youth-caregivers-and-pandemic (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological Models of Human Development. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 2nd ed.; Postlethwaite, T., Husen, T., Eds.; Elsevier Sciences, LTD: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 1643–1647. [Google Scholar]

- Tebb, S.; Jivanjee, P. Caregiver Isolation: An Ecological Model. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2000, 34, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Justice. Olmstead: Community Integration for Everyone. Available online: https://archive.ada.gov/olmstead/index.html (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- Levine, C.; Snyder, R. Family Caregivers: The Unrecognized Strength Behind Hospital at Home. Health Affairs 2021. Available online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/family-caregivers-unrecognized-strength-behind-hospital-home (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving. Caregivers in Crisis: Caregiving in the Time of COVID-19; Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving: Americus, GA, USA, 2020; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- University of Pittsburgh. Effects of COVID-19 on Family Caregivers; University of Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, J. Food deserts: Governing obesity in the neoliberal city. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2014, 38, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Balcazar, Y.; Redmond, L.; Kouba, J.; Hellwig, M.; Davis, R.; Martinez, L.I.; Jones, L. Introducing systems change in the schools: The case of school luncheons and vending machines. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007, 39, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokols, D. Establishing and Maintaining Healthy Environments toward a Social Ecology of Health Promotion. Am. Psychol. 1992, 47, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokols, D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996, 10, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcleroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs. Health Educ. Behav. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N. Measures of racism, sexism, heterosexism, and gender binarism for health equity research: From structural injustice to embodied harm-an ecosocial analysis. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 41, 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noursi, S.; Saluja, B.; Richey, L. Using the Ecological Systems Theory to Understand Black/White Disparities in Maternal Morbidity and Mortality in the United States. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2021, 8, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, N.; Davison, C. Strengthening Communities with a Socio-Ecological Approach: Local and International Lessons in Whole Systems. In Ecosystems, Society and Health: Pathways through Diversity, Convergence, and Integration; Hallström, L., Guehlstorf, N.P., Parkes, M.W., Eds.; McGill-Queens University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2015; pp. 33–67. ISBN 9780773544796. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, T.; Kreuter, M. Using Written Narratives in Public Health Practice: A Creative Writing Perspective. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, E94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertz, M.; Nosek, M.; McNiesh, S.; Marlow, E. The composite first person narrative: Texture, structure, and meaning in writing phenomenological descriptions. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2011, 6, 5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, C.C.; Flores, L.; Rosenthal, A. What a Story Can Do: Building Empathy to Change School Food Policy & Practice. In Transforming School Food Politics around the World; Gaddis, J.E., Robert, S.A., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; ISBN 9780262548113. [Google Scholar]

- Ornstein-Sloan, M.T. Re-framing Informal Family Caregiving. Ph.D. Dissertation, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA, 2016. Available online: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1723&context=gc_etds (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- Morris, J.C.; Greentree, V.W.; Taylor, J.A. The Myth of the Rugged Individual: Implications for Public Administration, Civic Engagement, And Civil Society. Va. Soc. Sci. J. 2014, 49, 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, C.R.; Rhames, K. In their own words: The experience and needs of children in younger-onset Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias families. Dementia 2018, 17, 337–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendricks, B.A.; Kavanaugh, M.S.; Bakitas, M.A. How Far Have We Come? An Updated Scoping Review of Young Carers in the U.S. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2021, 38, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh, M.S.; Stamatopoulos, V.; Cohen, D.; Zhang, L. Unacknowledged Caregivers: A Scoping Review of Research on Caregiving youth in the United States. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2016, 1, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastawrous, M.; Gignac, M.A.; Kapral, M.K.; Cameron, J.I. Factors that contribute to adult children caregivers’ well-being: A scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community 2015, 23, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Security Caregiver Credit Act, S.1211, 118th Cong. 2023. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/1211/text?s=1&r=1 (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- Arno, P.S.; Levine, C.; Memmott, M.M. The economic value of informal caregiving. Health Aff. 1999, 18, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Family Support. COVID-19 Vaccine Eligibility for Caregivers. Available online: https://www.caregiving.pitt.edu/covid-19-vaccine-eligibility-for-caregivers/ (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Caregiving Youth Research Collaborative. Report on Caregiving Youth in the U.S. 2023. Available online: https://aacy.org/what-we-do/caregiving-youth-institute/research-collaboration/ (accessed on 6 January 2024).

- Clark, M.; Standard, P.L. Caregiver burden and the structural family model. Fam. Community Health 1996, 18, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bronfenbrenner | Current Conceptualization | SEM Application | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Child (theory of development) | Care receiver | Caregiving unit (care receiver, family caregivers, paid caregivers) |

| Microsystem | Family, peers, schools, services, church | Family, home, delivery of services in the home (paid caregivers) | Reconfiguration of households and families of choice who fill roles in a variety of ways; paid care |

| Mesosystem | Neighborhood, social organizations, physical environment (urban, suburban, rural) | Same, with a focus on home and community-based service providers (i.e., home care agencies) | Universal and participatory family-centered design of services, which are flexible, inclusive, and responsive |

| Exosystem | Social services (organization of services), local politics, industry, mass media, government | Limited welfare state (SSD, SNAP (Social Security Disability and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program)); for-profit social services (i.e., respite); invisibility of care/limited coverage of care in media | Universal care policies, including paid family leave; workplace policies; Universal Basic Income (UBI); SS Caregiver Credit Act; state and federal policies |

| Macrosystem | Cultural and political ideologies; regulatory and constitutional frameworks | Personal responsibility (i.e., individualism, neoliberalism); care as women’s work | Collectivism; interdependence; gender equity in relation to caregiving |

| Chronosystem | Change over time: socio-historical conditions or patterns of events and transitions over a life course | Caregiving is present from onset through the life course with no accounting for different life stages | Responses to care are life course sensitive (caregiving youth: 8–18 years, young adult caregivers: 18–25) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ornstein, M.T.; Caruso, C.C. The Social Ecology of Caregiving: Applying the Social–Ecological Model across the Life Course. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010119

Ornstein MT, Caruso CC. The Social Ecology of Caregiving: Applying the Social–Ecological Model across the Life Course. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(1):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010119

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrnstein, Maggie T., and Christine C. Caruso. 2024. "The Social Ecology of Caregiving: Applying the Social–Ecological Model across the Life Course" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 1: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010119

APA StyleOrnstein, M. T., & Caruso, C. C. (2024). The Social Ecology of Caregiving: Applying the Social–Ecological Model across the Life Course. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(1), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010119