Self-Objectification, Disordered Eating and Sexual Orientation in Men

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Aim and Objectives

1.2. Hypotheses

- Heterosexual men will report lower levels of disordered eating, self-objectification and depressive symptoms than homosexual men.

- Significant, positive correlations will be observed between disordered eating, self-objectification and depressive symptoms in the entire sample.

- The association between sexual orientation (homosexual vs. heterosexual) and disordered eating will be mediated by self-objectification, depressive symptoms and BMI.

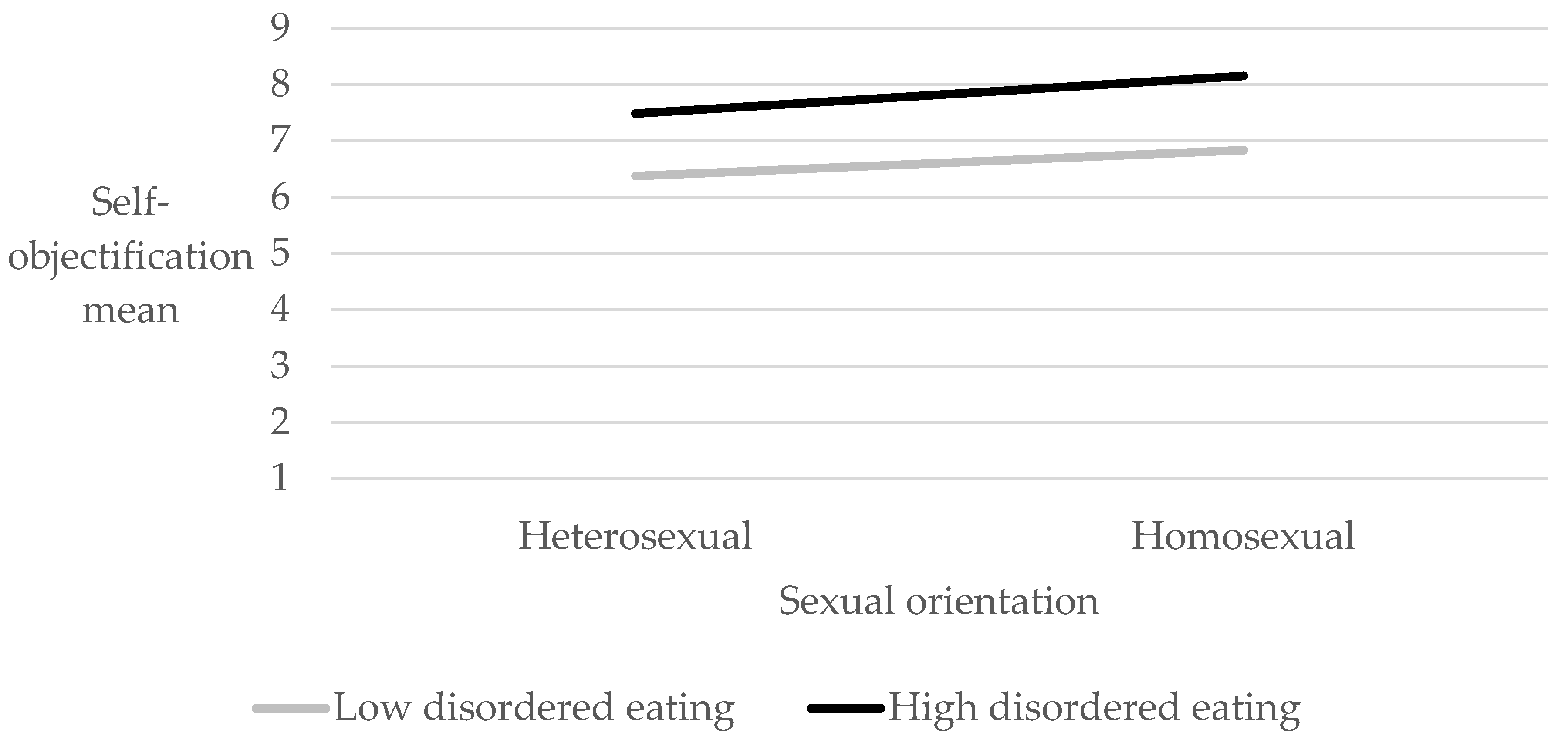

- Sexual orientation will moderate the association between disordered eating and self-objectification.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Demographic Variables

2.2.2. Sexual Orientation

2.2.3. Self-Objectification

2.2.4. Disordered Eating

2.2.5. Depressive Symptoms

2.3. Procedure

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disordered eating (EDE-Q-13) | 1. Total | 0.85 *** | 0.83 *** | 0.73 *** | 0.53 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.34 *** |

| 2. Eating restraint | 0.64 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.18 * | 0.25 *** | 0.17 * | 0.18 * | ||

| 3. Shape and weight concerns | 0.59 *** | 0.20 ** | 0.16 * | 0.40 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.22 ** | |||

| 4. Body dissatisfaction | 0.28 *** | 0.11 | 0.25 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.32 *** | ||||

| 5. Bingeing | 0.34 *** | 0.08 | 0.35 *** | 0.41 *** | |||||

| 6. Purging | 0.10 | 0.29 *** | 0.12 | ||||||

| 7. Self-objectification (LSOQ) | 0.13 | 0.11 | |||||||

| 8. Depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) | 0.17 * | ||||||||

| 9. BMI |

References

- Paxton, S.J.; Damiano, S.R. The development of body image and weight bias in childhood. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 2017, 52, 269–298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Slater, A.; Tiggemann, M. The contribution of physical activity and media use during childhood and adolescence to adult women’s body image. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendo-Lázaro, S.; Polo-del-Río, M.I.; Amado-Alonso, D.; Iglesias-Gallego, D.; León-del-Barco, B. Self-concept in childhood: The role of body image and sport practice. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostanski, M.; Gullone, E. The impact of teasing on children’s body image. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2007, 16, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, V.X.; Jackson, A.C.; McKenzie, V.L. The effects of teasing in childhood or adolescence on young adults’ body image. Aust. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 28, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Nichols, T.E.; Damiano, S.R.; Wertheim, E.H.; Paxton, S.J. Low body esteem and dietary restraint among 7-year old children: The role of perfectionism, low self-esteem, and belief in the rewards of thinness and muscularity. Eat. Behav. 2019, 32, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbert, R. Newman’s Complaint. Available online: https://www.esquire.com/news-politics/a21538/roger-ebert-paul-newman/2013 (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Pöhlmann, K.; Roth, M.; Brähler, E.; Joraschky, P. The Dresden Body Image Inventory (DKB-35): Validity in a clinical sample. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2013, 64, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M.; Frankenhauser, H.; Roberts, T.A. Objects of desire: Objectification as a function of male sexual orientation. Psychol. Men Masculinities 2009, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pennesi, J.L.; Wade, T.D. A systematic review of the existing models of disordered eating: Do they inform the development of effective interventions? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 43, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Roberts, T.A.; Noll, S.M.; Quinn, D.M.; Twenge, J.M. That swimsuit becomes you: Sex differences in self-objectification, restrained eating, and math performance. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.M.; Daniels, E.A.; Zurbriggen, E.L.; Rosenscruggs, D. The sources and consequences of sexual objectification. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 2, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L. A Review of Self-Objectification Research. World Sci. Res. 2022, 8, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, S.; Bridges, S.K.; Martens, M.P. The development and validation of the Male Assessment of Self-Objectification (MASO). Psychol. Men Masculinities 2014, 15, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehlhof, M.E.W.; Musher-Eizenman, D.R.; Neufeld, J.M.; Hauser, J.C. Self-objectification and ideal body shape for men and women. Body Image 2009, 6, 308–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelan, P.; Hargreaves, D. Reasons for exercise and body esteem: Men’s responses to self-objectification. Sex Roles 2005, 53, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogero, R.M.; Davis, W.N.; Thompson, J.K. The role of self-objectification in the experience of women with eating disorders. Sex Roles 2005, 52, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, S.M.; Fredrickson, B.L. A meditational model linking self- objectification, body-shame, and disordered eating. Psychol. Women Quart. 1998, 22, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M.; Kuring, J.K. The role of body objectification in disordered eating and depressed mood. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 43, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallsworth, L.; Wade, T.; Tiggemann, M. Individual differences in male body-image: An examination of self-objectification in recreational bodybuilders. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, J.S. Exposure to sexually objectifying media and body self-perceptions among college women: An examination of the selective exposure hypothesis and the role of moderating variables. Sex Roles 2006, 55, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choma, B.L.; Shove, C.; Busseri, M.A.; Sadava, S.W.; Hosker, A. Assessing the role of body image coping strategies as mediators or moderators of the links between self-objectification, body shame, and well-being. Sex Roles 2009, 61, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, Y.; Tiggemann, M.; Kirkbride, A. Those speedos become them: The role of self-objectification in gay and heterosexual men’s body image. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslow, A.S.; Sandil, R.; Brewster, M.E.; Parent, M.C.; Chan, A.; Yucel, A.; Bensmiller, N.; Glaeser, E. Adonis on the apps: Online objectification, self-esteem, and sexual minority men. Psychol. Men Masculinities 2020, 21, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naamani, M.; El Jamil, F. Correlates of disordered eating among gay men in Lebanon. Eat. Behav. 2021, 40, 101477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, M.E.; Erchull, M.J.; Liss, M.; Turner, D.L.; Nelson, J.A.; Ramsey, L.R.; Hurt, M. Predictors and effects of self-objectification in lesbians. Psychol. Women Quart. 2008, 32, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noffsinger-Frazier, N.A. Objectification Theory and Disordered Eating: The Impact of Feminist Identification, Internalization of Sociocultural Standards of Appearance, and Sexual Orientation; The University of Memphis: Memphis, TN, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Roberts, T.A. Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychol. Women Quart. 1997, 21, 173–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, D.M.R.; Santos, G.F.D.S.; Nardi, A.E. Binge eating disorder and depression: A systematic review. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 11, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, Y.L.; Samy, A.L.; Tong, W.T.; Islam, M.A.; Low, W.Y. Eating disorder among Malaysian University students and its associated factors. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2020, 32, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, J.; Moessner, M.; Bauer, S. Depression, anxiety and eating disorder-related impairment: Moderators in female adolescents and young adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.A.; Griffiths, K.M. Self-objectification and depression: An integrative systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 171, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabe, S.; Hyde, J.S.; Lindberg, S.M. Body objectification and depression in adolescents: The role of gender, shame, and rumination. Psychol. Women Quart. 2007, 31, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impett, E.A.; Henson, J.M.; Breines, J.G.; Schooler, D.; Tolman, D.L. Embodiment feels better: Girls’ body objectification and well-being across adolescence. Psychol. Women Quart. 2011, 35, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsey, A.C.; Pomeroy, W.B.; Martin, C.E. Sexual Behavior in the Human Male; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Gigi, I.; Bachner-Melman, R.; Lev-Ari, L. The association between sexual orientation, susceptibility to social messages and disordered eating in men. Appetite 2016, 99, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollast, R.; Klein, O.; VanLeeuwen, D.M.; Gervais, S.J.; Bernard, P. Does self-objectification entail an opposition between appearance and competence? The Likert version of the Self-Objectification Questionnaire (LSOQ). Psychol. Belg. 2021, 61, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lev-Ari, L.; Bachner-Melman, R.; Zohar, A.H. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q-13): Expanding on the short form. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Beglin, S.J. Eating disorder examination questionnaire. Cogn. Behav. Ther. Eat. Disord. 2008, 309, 313. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doi, S.; Ito, M.; Takebayashi, Y.; Muramatsu, K.; Horikoshi, M. Factorial validity and invariance of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 among clinical and non-clinical populations. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.E.; Lee, B. The psychometric properties of the patient health questionnaire-9 in a sample of Korean university students. Psychiatry Investig. 2019, 16, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melamed, S.; Shirom, A.; Toker, S.; Berliner, S.; Shapira, I. Association of fear of terror with low-grade inflammation among apparently healthy employed adults. Psychos. Med. 2004, 66, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Engeln-Maddox, R.; Miller, S.A.; Doyle, D.M. Tests of objectification theory in gay, lesbian, and heterosexual community samples: Mixed evidence for proposed pathways. Sex Roles 2011, 65, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, M.S.; Parent, M.C.; Moradi, B. Does exposure to muscularity-idealizing images have self-objectification consequences for heterosexual and sexual minority men? Psych. Men Masculinity 2013, 14, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siever, M.D. Sexual orientation and gender as factors in socioculturally acquired vulnerability to body dissatisfaction and eating disorders. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1994, 62, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, A.; Kaplan, J.A.; Austin, S.B.; Davison, K.; Lopez, G.; Agénor, M. “It’s all outward appearance-based attractions”: A qualitative study of body image among a sample of young gay and bisexual men. J. Gay Lesb. Ment. Health 2020, 24, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, M.; Semlyen, J.; Tai, S.; Killaspy, H.; Osborn, D.; Popelyuk, D.; Nazareth, I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self-harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psych. 2008, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenkman, G.; Stein, Y.; Bos, H. The mediating role of attachment avoidance in the association between sexual orientation and mental health. J. Homosex. 2021, 68, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, L.L.; Harriger, J.A. Eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors in the LGBT population: A review of the literature. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbaniang, I.; Rose, E.; Moodie, E.E.; Hart, T.A.; Cox, J. Mental health services use and depressive symptom scores among gay and bisexual men in Canada. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 2333–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpa, J.G. A New Measure of Body Dissatisfaction and Its Relation to Self-Objectification, Eating Disorders, and Depression in Gay and Heterosexual Men; Alliant International University: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Grabe, S.; Jackson, B. Self-objectification and depressive symptoms: Does their association vary among Asian American and White American men and women? Body Image 2009, 6, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.F.; Russo, N.F. Measurement invariance and the role of body consciousness in depressive symptoms. Psychol. Women Quart. 2010, 34, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakanalis, A.; Di Mattei, V.E.; Bagliacca, E.P.; Prunas, A.; Sarno, L.; Riva, G.; Zanetti, M.A. Disordered eating behaviors among Italian men: Objectifying media and sexual orientation differences. In Current Findings on Males with Eating Disorders; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, R. Adolescent body image: Relationships with self-objectification, shame, depressed mood and anxious symptoms. Diss. Abstr. Int. Sect. B Sci. Eng. 2009, 69, 6405. [Google Scholar]

- Gulec, H.; Torun, T.; Prado, A.D.S.; Bauer, S.; Rummel-Kluge, C.; Kohls, E. Eating attitudes and depressive symptoms in a LGBTIQ sample in Turkey. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1014253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis-Smith, H.; Bray, I.; Salmon, D.; Slater, A. Prospective pathways to depressive symptoms and disordered eating in adolescence: A 7-year longitudinal cohort study. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 2060–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahlan, R.N.; Williams, B.M.; Forrest, L.N.; Saunders, J.F.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Levinson, C.A. Disordered eating, self-esteem, and depression symptoms in Iranian adolescents and young adults: A network analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiggemann, M. Mental health risks of self-objectification: A review of the empirical evidence for disordered eating, depressed mood, and sexual dysfunction. In Self-Objectification in Women: Causes, Consequences, and Counteractions; Calogero, R.M., Tantleff-Dunn, S., Thompson, J.K., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschmidt, A.B.; Wall, M.; Choo, T.H.J.; Becker, C.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Shared risk factors for mood-, eating-, and weight-related health outcomes. Health Psychol. 2016, 35, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornioli, A.; Lewis-Smith, H.; Smith, A.; Slater, A.; Bray, I. Adolescent body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: Predictors of later risky health behaviours. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 238, 112458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.; Mellor, D.; Brann, P. Factors associated with dropout and diagnosis in child and adolescent mental health services. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2009, 43, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slane, J.D.; Burt, S.A.; Klump, K.L. Genetic and environmental influences on disordered eating and depressive symptoms. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2011, 44, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, M.C.; Moradi, B. Body image and eating disorder symptoms in sexual minority men: A test and extension of objectification theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2010, 57, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyders, G.C. Body image and attitudes toward eating: The influence of objectified body consciousness and variations by gender and sexual orientation. Diss. Abstr. Int. Sect. B Sci. Eng. 1999, 60, 1861. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, L.M.; Thompson, J.K. Self-objectification and disordered eating: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Heterosexual (n = 108) Mean (SD) | Homosexual (n = 107) Mean (SD) | F(1,212) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 33.59 (8.96) | 31.27 (6.75) | 4.56 * |

| BMI | 25.08 (3.96) | 23.75 (3.24) | 7.23 ** |

| Education (years) | 14.03 (3.04) | 14.38 (3.03) | 0.73 |

| Mother’s education | 13.75 (3.17) | 13.05 (3.41) | 2.42 |

| Father’s education | 13.51 (4.07) | 12.26 (4.11) | 5.02 * |

| Number of children | 0.85 (1.26) | 0.11 (0.50) | 31.50 *** |

| Variable | Heterosexual (n = 108) N (%) | Homosexual (n = 107) N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship status | |||

| Not in a relationship | 37 (35.9%) | 56 (53.8%) | |

| In a relationship | 37 (35.9%) | 41 (39.4%) | |

| Married | 29 (28.2%) | 7 (6.7%) | = 17.53 *** |

| Religiosity | |||

| Secular | 77 (71.3%) | 87 (81.3%) | |

| Traditional | 17 (16.2%) | 12 (11.9%) | |

| Orthodox | 11 (10.5%) | 2 (2.0%) | = 7.63 * |

| Self-Objectification (LSOQ) | Depressive Symptoms (PHQ-9) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disordered eating (EDE-Q-13) total | 0.35 *** | 0.40 *** | |

| Eating restraint | 0.26 *** | 0.20 ** | |

| Shape and weight concerns | 0.42 *** | 0.35 *** | |

| Body dissatisfaction | 0.27 *** | 0.31 *** | |

| Bingeing | 0.16 | 0.39 *** | |

| Purging | 0.11 | 0.30 *** | |

| Self-objectification (LSOQ) | 0.15 * | ||

| BMI | 0.11 | 0.17 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bachner-Melman, R.; Lev-Ari, L.; Tiram, H.; Zohar, A.H. Self-Objectification, Disordered Eating and Sexual Orientation in Men. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010106

Bachner-Melman R, Lev-Ari L, Tiram H, Zohar AH. Self-Objectification, Disordered Eating and Sexual Orientation in Men. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2024; 21(1):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010106

Chicago/Turabian StyleBachner-Melman, Rachel, Lilac Lev-Ari, Hadar Tiram, and Ada H. Zohar. 2024. "Self-Objectification, Disordered Eating and Sexual Orientation in Men" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 21, no. 1: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010106

APA StyleBachner-Melman, R., Lev-Ari, L., Tiram, H., & Zohar, A. H. (2024). Self-Objectification, Disordered Eating and Sexual Orientation in Men. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21010106