Factors Affecting Remote Workers’ Job Satisfaction in Utah: An Exploratory Study

Abstract

1. Introduction, Purpose, and Objectives

2. Literature Review

2.1. Work Environments

2.2. Work Redesign

2.3. Ability, Motivation, Opportunity Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Population and Sample

3.2. Instrument Design

3.3. Description of Study Constructs

3.4. Summary Statistics of Constructs

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

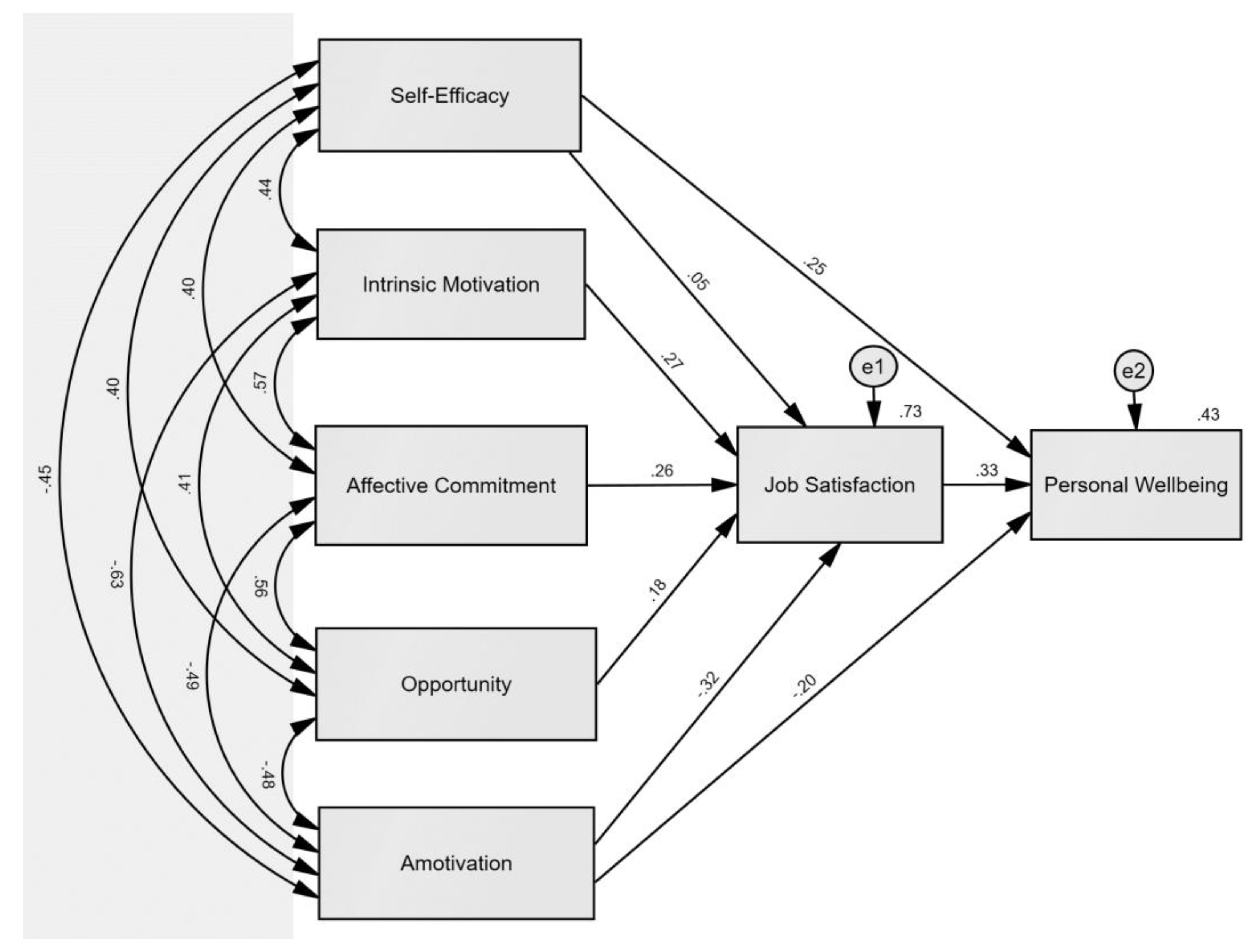

4.1. Objective (a): Predictors of Job Satisfaction

4.2. Objective (b): Predictors of Personal Wellbeing

4.3. Objective (c): Mapping Predictors of Job Satisfaction and Personal Wellbeing

4.4. Objective (d): The Role of HR Bundles and Organizational Culture

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Recommendations and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Domain | Construct (No. of Items) | Interpretation | Original Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ability (A) | Self-Efficacy (8) | One’s self-assessed capability to execute a behavior to produce certain outcomes. | [81] |

| Motivation (M) | Intrinsic Motivation (4) | Performing an activity for pleasure and satisfaction inherent in the activity itself. | [82] |

| External Regulation (4) | Performing an activity for external rewards or to avoid negative consequences. | ||

| Identified Regulation (4) | Performing an activity because it is perceived as valued/important and self-chosen. | ||

| Amotivation (4) | Performing an activity even though there is no sense of perceived purpose or expectation of its value. | ||

| Opportunity (O) | Opportunity (4) | One’s level of participation in the decision-making process of the organization, measured as ‘Employee Involvement’. | [48,83] |

| HR Bundles (Policies) | Ability-Enhancing (5) | HR policies to improve employees’ ability to perform in their roles (e.g., training opportunities). | [83] |

| Motivation-Enhancing (6) | HR policies to reward employees based on performance (e.g., internal rewards, bonuses). | ||

| Staffing Policies (4) | HR policies to screen and select the ‘right’ candidate for the role (e.g., structured interviews). | [84] | |

| Internal Mobility (3) | HR policies that facilitate an internal promotion process for the upward mobility of employees (e.g., career ladder). | ||

| Job Security (2) | HR policies that provide employees with a sense of longevity and security in the role (e.g., long-term contracts). | ||

| Job Description (3) | HR policies that provide employees with a clear and up-to-date description of their responsibilities. | ||

| Results-Oriented Appraisal (3) | HR policies that enable a fair and objective performance review system (e.g., annual reviews). | ||

| Organizational Culture | LMX: Supervisor Relationship (8) | Perceived quality of the relationship between an employee and their immediate supervisor (adaptation of the LMX-7). | [85] |

| Work Culture (9) | Perceived level of cohesion, support, and openness between organizational leaders and employees (adaptation of the Corporate Culture Scale—Short Form). | [86]; Original German version—[87] | |

| Teamwork (6) | Perceived level of teamworking between employees to effectively attain desired performance outcomes (adaptation of the Internal Participation Scale). | [88] | |

| Organizational Commitment | Affective Commitment (5) | One’s emotional attachment to the goals and values of the organization (i.e., ‘want to stay’). | [68] |

| Continuance Commitment (7) | One’s perception towards the personal cost of leaving the organization (i.e., ‘need to stay’). | ||

| Normative Commitment (6) | One’s perception of their moral obligation to stay with the organization (i.e., ‘ought to stay’). | ||

| Outcome 1 | Job Satisfaction (5) | One’s general level of satisfaction with their employment (Short Index of Job Satisfaction—SIJS) | [89] |

| Outcome 2 | Personal Wellbeing (12) | A measure of an individual’s level of psychological distress based on the GHQ-12. | [78] |

References

- Locke, E.A. What Is Job Satisfaction? Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1969, 4, 309–336. Available online: https://www.libs.uga.edu/reserves/docs/scans/job%20satisfaction.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- Locke, E.A. Job satisfaction and job performance: A theoretical analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1970, 5, 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćulibrk, J.; Delić, M.; Mitrović, S.; Ćulibrk, D. Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Job Involvement: The Mediating Role of Job Involvement. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motowidlo, S.J. Job Performance. In Handbook of Psychology: Industrial and Organizational Psychology; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siengthai, S.; Pila-Ngarm, P. The interaction effect of job redesign and job satisfaction on employee performance. Evid.-Based HRM Glob. Forum Empir. Sch. 2016, 4, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control. CDC Museum COVID-19 Timeline; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html#:~:text=March%2011%2C%202020,declares%20COVID%2D19%20a%20pandemic (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Bartik, A.W.; Bertrand, M.; Cullen, Z.; Glaeser, E.L.; Luca, M.; Stanton, C. The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 17656–17666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, L.D.; System, B.O.G.O.T.F.R.; Decker, R.A.; Flaaen, A.; Hamins-Puertolas, A.; Kurz, C. Business Exit During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Non-Traditional Measures in Historical Context. Finance Econ. Discuss. Ser. 2021, 2021, 103419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, S.; Schmidt, A.M.; Madjar, N. Working from home during COVID-19: A study of the interruption landscape. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 1448–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Wang, X.; Han, X.; Huang, S.; Huang, D. The dark side of remote working during pandemics: Examining its effects on work-family conflict and workplace wellbeing. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 79, 103174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, S.; Ipsen, C. In times of change: How distance managers can ensure employees’ wellbeing and organizational performance. Saf. Sci. 2017, 100, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N.; Han, R.; Liang, J. How Hybrid Working from Home Works out; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M. Gartner Survey Reveals 82% of Company Leaders Plan to Allow Employees to Work Remotely Some of the Time [Press Release]. 14 July 2020. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2020-07-14-gartner-survey-reveals-82-percent-of-company-leaders-plan-to-allow-employees-to-work-remotely-some-of-the-time (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Barrero, J.M.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S. Why Working from Home Will Stick; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, P.; Lipowska, K.; Smoter, M. Mismatch in Preferences for Working from Home—Evidence from Discrete Choice Experiments with Workers and Employers: Evidence from Poland, IBS Working Paper WP 05/2022. 2022. Available online: https://ibs.org.pl/en/publications/mismatch-in-preferences-for-working-from-home-evidence-from-discrete-choice-experiments/ (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Aksoy, C.G.; Barrero, J.M.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.; Dolls, M.; Zarate, P. Working from Home Around the World; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N.A.; Khazon, S.; Meyer, R.D.; Burrus, C.J. Situational Strength as a Moderator of the Relationship Between Job Satisfaction and Job Performance: A Meta-Analytic Examination. J. Bus. Psychol. 2013, 30, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.A.; Cropanzano, R.; Bonett, D.G. The moderating role of employee positive well being on the relation between job satisfaction and job performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, S.; Parumasur, S.B. The relationship between employee motivation and job involvement. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2010, 13, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.B. Effects of Human Resource Systems on Manufacturing Performance and Turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 670–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.B. The Link between Business Strategy and Industrial Relations Systems in American Steel Minimills. ILR Rev. 1992, 45, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Control: Organizational and Economic Approaches. Manag. Sci. 1985, 31, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.S.; Pearce, J.L.; Porter, L.W.; Hite, J.P. Choice of employee-organization relationship: Influence of external and internal organizational factors. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1995, 13, 117–151. Available online: https://escholarship.org/content/qt2nc1b8v9/qt2nc1b8v9_noSplash_02136d90982d8ef639c5684dafa441a3.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Tsui, A.S.; Pearce, J.L.; Porter, L.W.; Tripoli, A.M. Alternative Approaches to the Employee-Organization Relationship: Does Investment in Employees Pay Off? Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 1089–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Lepak, D.P.; Hu, J.; Baer, J.C. How Does Human Resource Management Influence Organizational Outcomes? A Meta-analytic Investigation of Mediating Mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1264–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G.C. Social Behavior as Exchange. Am. J. Sociol. 1958, 63, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.A. “Factors Explaining Remote Work Adoption in the United States”. All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 8087. 2021. Available online: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/8087 (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Qian, J.; Parker, S.K. Achieving Effective Remote Working During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Work Design Perspective. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 70, 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilles, J. Telecommunications and Organizational Decentralization. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1975, 23, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R. Work redesign and motivation. Prof. Psychol. 1980, 11, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Lawler, E.E. Employee reactions to job characteristics. J. Appl. Psychol. 1971, 55, 259–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmann, L.; Hübler, O. Working from home, job satisfaction and work–life balance—Robust or heterogeneous links? Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 42, 424–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulińska-Stangrecka, H.; Bagieńska, A. The Role of Employee Relations in Shaping Job Satisfaction as an Element Promoting Positive Mental Health at Work in the Era of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratowicz, B.; Godlewska-Werner, D.; Połomski, P.; Khosla, M. Satisfaction with job and life and remote work in the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of perceived stress, self-efficacy and self-esteem. Curr. Issues Pers. Psychol. 2021, 10, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, F.; Zappalà, S. Social Isolation and Stress as Predictors of Productivity Perception and Remote Work Satisfaction during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Concern about the Virus in a Moderated Double Mediation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmann, L.; Hübler, O. Job Satisfaction and Work-Life Balance: Differences between Homework and Work at the Workplace of the Company; IZA Discussion Paper No. 13504; Bonn Institute of Labor Economics: Bonn, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3660250 (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Golden, T.D. Telework and the Navigation of Work-Home Boundaries. Organ. Dyn. 2021, 50, 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrics. 2022 Employee Experience Trends. 2021. Available online: https://success.qualtrics.com/rs/542-FMF-412/images/Qualtrics%20-%202022%20Employee%20Experience%20Trends%20Report.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Bailey, T.R. Discretionary Effort and the Organization of Work: Employee Participation and Work Reform since Hawthorne; Teachers College and Conservation of Human Resources, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum, E.; Bailey, T.; Berg, P.; Kalleberg, A.L. Manufacturing Advantage: Why High Performance Systems Pay Off; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán-Martín, I.; Bou-Llusar, J.C. Examining the intermediate role of employee abilities, motivation and opportunities to participate in the relationship between HR bundles and employee performance. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2018, 21, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brayfield, A.H.; Crockett, W.H. Employee attitudes and employee performance. Psychol. Bull. 1955, 52, 396–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, M.; Pringle, C.D. The Missing Opportunity in Organizational Research: Some Implications for a Theory of Work Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, N.R.F. Psychology in Industry, 2nd ed.; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1955; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1955-09057-000 (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Vroom, V.H. Work and Motivation; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964; Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Work+and+Motivation-p-9780787900304 (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Choi, J.-H. The HR-performance link using two differently measured HR practices. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2014, 52, 370–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Garcia, J.A.; Martinez-Tomas, J. Deconstructing AMO framework: A systematic review. Intang. Cap. 2016, 12, 1040–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.; Berg, P.; Sandy, C. The Effect of High-Performance Work Practices on Employee Earnings in the Steel, Apparel, and Medical Electronics and Imaging Industries. ILR Rev. 2001, 54, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P.; Steeneveld, M. Human Resource Strategy and Competitive Advantage: A Longitudinal Study of Engineering Consultancies. J. Manag. Stud. 1999, 36, 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boselie, P. A Balanced Approach to Understanding the Shaping of Human Resource Management in Organisations. Manag. Rev. 2009, 20, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, C. Theoretic insights on the nature of performance synergies in human resource systems: Toward greater precision. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2010, 20, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, J.; Liu, Y.; Hall, A.; Ketchen, D. How much do high-performance work practices matter? A meta-analysis of their effects on organizational performance. Pers. Psychol. 2006, 59, 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, E.; Berg, P. High-Performance Work Systems and Labor Market Structures. In Sourcebook of Labor Markets; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delery, J.E.; Shaw, J.D. The strategic management of people in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and extension. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 165–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ary, D.; Jacobs, L.C.; Sorensen, C.K.; Walker, D. Introduction to Research in Education, 9th ed.; Wadsworth: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Serdar, C.C.; Cihan, M.; Yücel, D.; A Serdar, M. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: Simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem. Medica 2021, 31, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A. A Meta-Analysis of Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhachek, A.; Coughlan, A.T.; Iacobucci, D. Results on the Standard Error of the Coefficient Alpha Index of Reliability. Mark. Sci. 2005, 24, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, P.J.; West, S.G.; Finch, J.F. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. An Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling. Fam. Sci. Rev. 2021, 11, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, E. Effects of skewness and kurtosis on normal-theory based maximum likelihood test statistic in multilevel structural equation modeling. Behav. Res. Methods 2011, 43, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. The Jackknife, the Bootstrap and Other Resampling Plans; CBMS-NSF Regional Conference Series in Applied Mathematics, Monograph 38; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lola, M.S.; David, A.; Zainuddin, N.H. Bootstrap Approaches to Autoregressive Model on Exchange Rates Currency. Open J. Stat. 2016, 06, 1010–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stine, R. An Introduction to Bootstrap Methods. Sociol. Methods Res. 1989, 18, 243–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Lee, J.; Gupta, V.; Cho, G. Comparison of Bootstrap Confidence Interval Methods for GSCA Using a Monte Carlo Simulation. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picheny, V.; Kim, N.H.; Haftka, R.T. Application of bootstrap method in conservative estimation of reliability with limited samples. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2009, 41, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musek, J.; Polic, M. Personal Well-Being. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 4752–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.E. Applied Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, J.J. Structural Equation Modelling. In Application for Research and Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.P.; Gater, R.; Sartorius, N.; Ustun, T.B.; Piccinelli, M.; Gureje, O.; Rutter, C. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol. Med. 1997, 27, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsen, C.; Kirchner, K.; Andersone, N.; Karanika-Murray, M. Becoming a Distance Manager: Managerial Experiences, Perceived Organizational Support, and Job Satisfaction During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 916234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Parker, S.K. How Does the Use of Information Communication Technology Affect Individuals? A Work Design Perspective. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 695–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyns, B.; von Collani, G. A new occupational self-efficacy scale and its relation to personality constructs and organizational variables. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2002, 11, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, F.; Vallerand, R.J.; Blanchard, C. On the Assessment of Situational Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: The Situational Motivation Scale (SIMS). Motiv. Emot. 2000, 24, 175–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, T.M.; Moynihan, L.M.; Park, H.J.; Wright, P.M. Beginning to Unlock the Black Box in the HR Firm Performance Relationship: The Impact of HR Practices on Employee Attitudes and Employee Outcomes; Working Paper No. 01-12. Cornell University, School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2001. Available online: https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/77407 (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Sun, L.-Y.; Aryee, S.; Law, K.S. High-Performance Human Resource Practices, Citizenship Behavior, and Organizational Performance: A Relational Perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, M.; Wirtz, M.A.; Bengel, J.; Göritz, A.S. Relationship of organizational culture, teamwork and job satisfaction in interprofessional teams. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jöns, I.; Hodapp, M.; Weiss, K. Kurzskala zur Erfassung der Unternehmenskultur; Researchgate: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, M.; A Wirtz, M. Development and psychometric properties of a scale for measuring internal participation from a patient and health care professional perspective. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013, 13, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinval, J.; Marôco, J. Short Index of Job Satisfaction: Validity evidence from Portugal and Brazil. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Domain | Construct | Min. | Max. | Mean | SD 1 | A 2 | S 3 | K 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ability (A) | Self-Efficacy | 1 | 100 | 82.64 | 15.77 | 0.92 | 1.16 | 1.14 |

| Motivation (M) | Intrinsic Motivation | 1 | 5 | 3.68 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 0.64 | 0.04 |

| External Regulation | 1 | 5 | 3.76 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.32 | |

| Identified Regulation | 1 | 5 | 3.95 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 1.08 | 1.42 | |

| Amotivation | 1 | 5 | 2.07 | 1.02 | 0.90 | 0.58 | 0.84 | |

| Opportunity (O) | Opportunity | 1 | 5 | 3.56 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.42 | 0.20 |

| HR-Bundles (Policies) | Ability-Enhancing | 1 | 5 | 3.43 | 1.01 | 0.89 | 0.35 | 0.71 |

| Motivation-Enhancing | 1 | 5 | 3.16 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 0.30 | 0.82 | |

| Staffing Policies | 1 | 5 | 3.75 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.52 | 0.08 | |

| Internal Mobility | 1 | 5 | 3.57 | 0.88 | 0.74 | 0.18 | 0.52 | |

| Job Security | 1 | 5 | 3.93 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.24 | |

| Job Description | 1 | 5 | 3.83 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.47 | 0.58 | |

| Results-Oriented Appraisal | 1 | 5 | 3.63 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.21 | 0.28 | |

| Organizational Culture | LMX: Supervisor Relationship | 1 | 7 | 5.98 | 1.01 | 0.92 | 1.14 | 0.78 |

| Work Culture | 1 | 7 | 5.84 | 1.09 | 0.94 | 1.16 | 0.85 | |

| Teamwork | 1 | 5 | 4.15 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 1.20 | 2.00 | |

| Organizational Commitment | Affective Commitment | 1 | 7 | 4.79 | 1.63 | 0.91 | 0.44 | 0.77 |

| Continuance Commitment | 1 | 7 | 5.52 | 1.08 | 0.81 | 1.05 | 1.21 | |

| Normative Commitment | 1 | 7 | 4.07 | 1.44 | 0.89 | 0.02 | 0.69 | |

| Outcome 1 | Job Satisfaction | 1 | 7 | 4.76 | 1.44 | 0.90 | 0.55 | 0.28 |

| Outcome 2 | Personal Wellbeing: GHQ-12 | 1 | 5 | 3.57 | 0.72 | 0.90 | 0.27 | 0.20 |

| Factors | β | Bias | SE | p | 95% Confidence Interval [BC] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Income 1 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.60 | −0.18 | 0.10 |

| Self-Efficacy | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.52 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Intrinsic Motivation | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.00 *** | 0.21 | 0.74 |

| External Regulation | −0.09 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.23 | −0.24 | 0.05 |

| Identified Regulation | −0.12 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.43 | −0.44 | 0.24 |

| Amotivation | −0.39 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.00 *** | −0.63 | −0.15 |

| Opportunity | 0.39 | −0.01 | 0.15 | 0.01 * | 0.10 | 0.67 |

| Ability-Enhancing | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.54 | −0.15 | 0.26 |

| Motivation-Enhancing | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.22 | −0.07 | 0.33 |

| Staffing Policies | −0.19 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.11 | −0.43 | 0.04 |

| Internal Mobility | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 1.00 | −0.24 | 0.23 |

| Job Security | −0.09 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.37 | −0.28 | 0.10 |

| Job Description | −0.09 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.50 | −0.35 | 0.16 |

| Results-Oriented Appraisal | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.97 | −0.29 | 0.28 |

| LMX (Supervisor Relationship) | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.52 |

| Work Culture | −0.20 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.11 | −0.47 | 0.03 |

| Teamwork | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.27 | −0.13 | 0.53 |

| Affective Commitment | 0.22 | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.00 *** | 0.07 | 0.35 |

| Continuance Commitment | −0.10 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.22 | −0.27 | 0.08 |

| Normative Commitment | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.41 | −0.06 | 0.15 |

| Factors | β | Bias | SE | p | 95% Confidence Interval [BC] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Income 1 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.38 | −0.05 | 0.17 |

| Self-Efficacy | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 *** | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Intrinsic Motivation | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.12 | 0.85 | −0.27 | 0.16 |

| External Regulation | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.15 | −0.03 | 0.18 |

| Identified Regulation | −0.12 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.24 | −0.33 | 0.10 |

| Amotivation | −0.15 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.04 * | −0.30 | 0.00 |

| Opportunity | −0.11 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.29 | −0.31 | 0.14 |

| Ability-Enhancing | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.91 | −0.16 | 0.15 |

| Motivation-Enhancing | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.36 | −0.20 | 0.09 |

| Staffing Policies | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.16 | −0.04 | 0.28 |

| Internal Mobility | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.42 | −0.12 | 0.25 |

| Job Security | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.69 | −0.18 | 0.09 |

| Job Description | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.67 | −0.22 | 0.18 |

| Results-Oriented Appraisal | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.86 | −0.17 | 0.21 |

| LMX (Supervisor Relationship) | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.72 | −0.14 | 0.24 |

| Work Culture | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.67 | −0.12 | 0.17 |

| Teamwork | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.64 | −0.15 | 0.24 |

| Affective Commitment | −0.11 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.23 | 0.02 |

| Continuance Commitment | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.29 | −0.13 | 0.03 |

| Normative Commitment | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.55 | −0.06 | 0.10 |

| Job Satisfaction | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 *** | 0.10 | 0.41 |

| Self-Efficacy | Intrinsic Motivation | Affective Commitment | Opportunity | Amotivation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ability-Enhancing | 0.3 5*** | 0.36 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.44 *** | −0.32 *** |

| Motivation-Enhancing | 0.18 * | 0.18 * | 0.31 *** | 0.46 *** | −0.25 ** |

| Staffing Policies | 0.32 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.55 *** | 0.65 *** | −0.40 *** |

| Internal Mobility | 0.30 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.52 *** | −0.48 *** |

| Job Security | 0.26 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.42 *** | 0.50 *** | −0.35 *** |

| Job Description | 0.42 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.50 *** | −0.36 *** |

| Results-Oriented Appraisal | 0.41 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.55 *** | −0.31 *** |

| LMX: Supervisor Rel. | 0.50 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.46 *** | −0.46 *** |

| Work Culture | 0.47 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.62 *** | −0.45 *** |

| Teamwork | 0.43 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.58 *** | 0.61 *** | −0.51 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ali, A.D.; Narine, L.K.; Hill, P.A.; Bria, D.C. Factors Affecting Remote Workers’ Job Satisfaction in Utah: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095736

Ali AD, Narine LK, Hill PA, Bria DC. Factors Affecting Remote Workers’ Job Satisfaction in Utah: An Exploratory Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(9):5736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095736

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Amanda D., Lendel K. Narine, Paul A. Hill, and Dominic C. Bria. 2023. "Factors Affecting Remote Workers’ Job Satisfaction in Utah: An Exploratory Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 9: 5736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095736

APA StyleAli, A. D., Narine, L. K., Hill, P. A., & Bria, D. C. (2023). Factors Affecting Remote Workers’ Job Satisfaction in Utah: An Exploratory Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(9), 5736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095736