Examining Disparities in Current E-Cigarette Use among U.S. Adults before and after the WHO Declaration of the COVID-19 Pandemic in March 2020

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Multivariable Logistic Regression Analyses

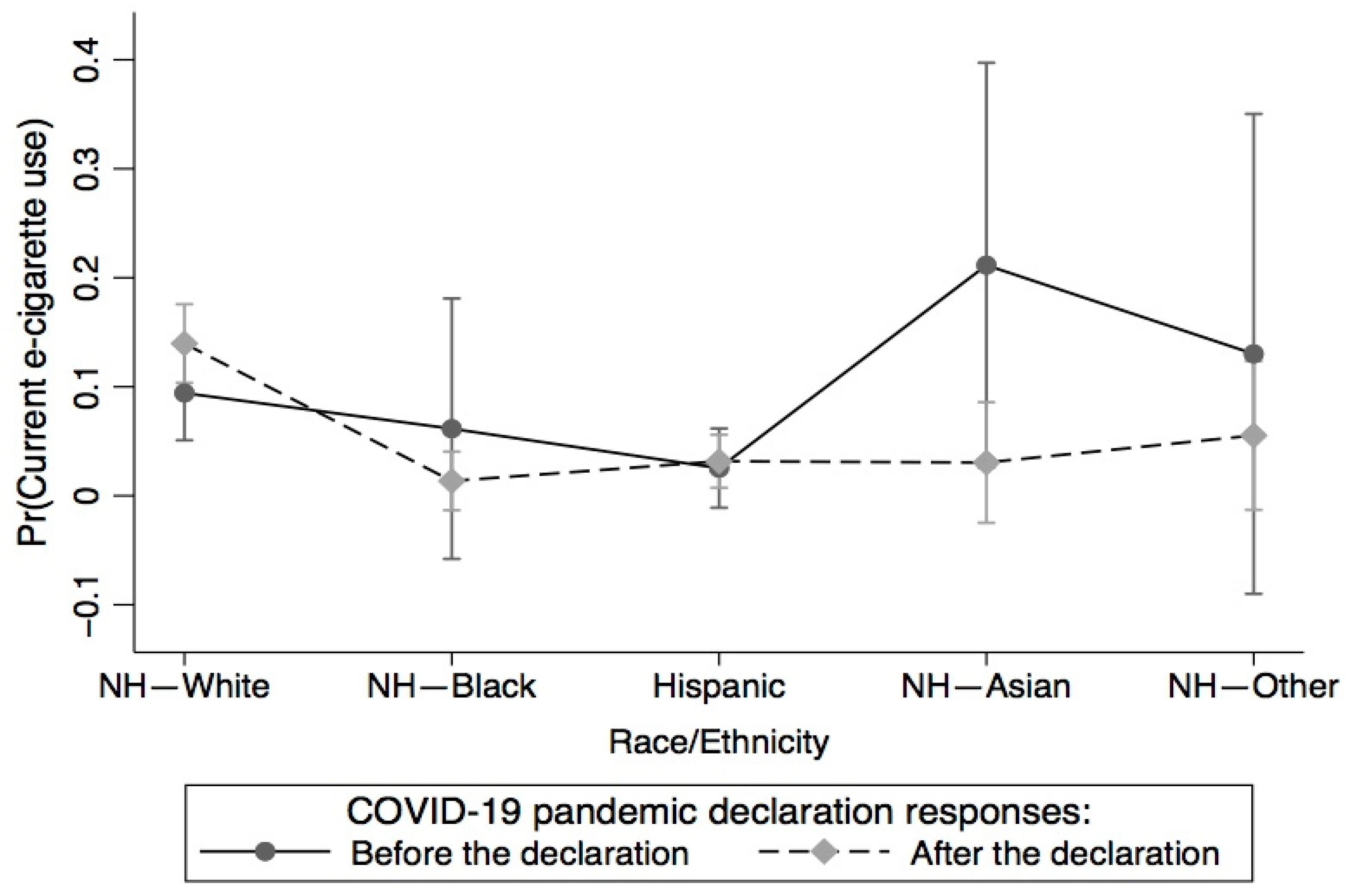

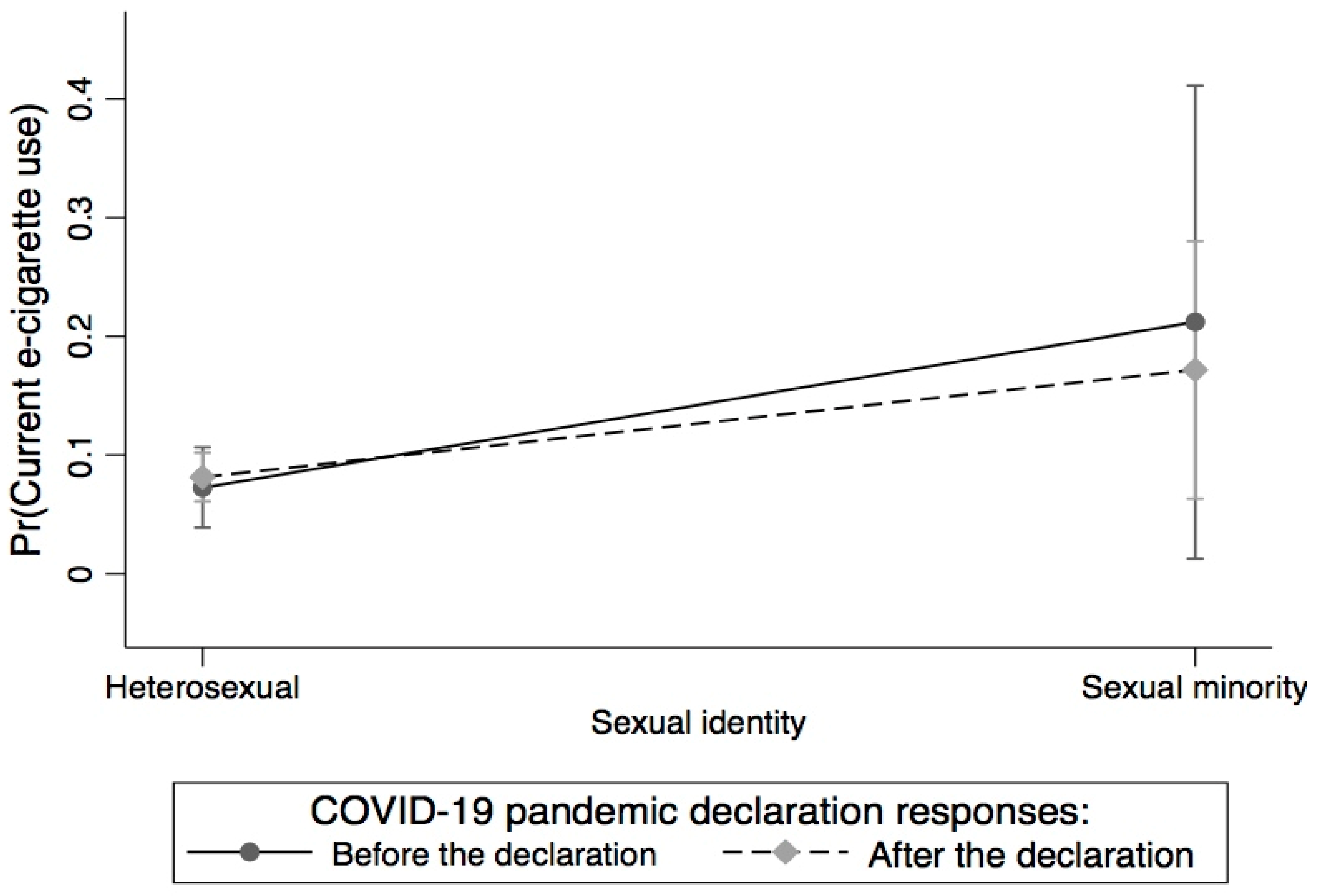

3.3. Between and within-Group Analyses

4. Discussion

Implications for Study Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CDC. Basics of COVID-19. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/your-health/about-covid-19/basics-covid-19.html (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, O.; Ogunyiola, A. A preliminary impact assessment of social distancing on food systems and greenhouse gas emissions. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2021, 31, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapru, S.; Vardhan, M.; Li, Q.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Saxena, D. E-cigarettes use in the United States: Reasons for use, perceptions, and effects on health. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette Use among Youth and Young Adults. A Report of the Surgeon General; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2016.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking Cessation. A Report of the Surgeon General; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020.

- Khadka, S.; Awasthi, M.; Lamichhane, R.R.; Ojha, C.; Mamudu, H.M.; Lavie, C.J.; Daggubati, R.; Paul, T.K. The Cardiovascular Effects of Electronic Cigarettes. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2021, 23, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan-Lyon, P. Electronic cigarettes: Human health effects. Tob. Control 2014, 23 (Suppl. S2), ii36–ii40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsalinos, K.E.; Kistler, K.A.; Pennington, A.; Spyrou, A.; Kouretas, D.; Gillman, G. Aldehyde levels in e-cigarette aerosol: Findings from a replication study and from use of a new-generation device. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 111, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polosa, R.; Morjaria, J.B.; Caponnetto, P.; Campagna, D.; Russo, C.; Alamo, A.; Amaradio, M.; Fisichella, A. Effectiveness and tolerability of electronic cigarette in real-life: A 24-month prospective observational study. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2014, 9, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardavas, C.I.; Anagnostopoulos, N.; Kougias, M.; Evangelopoulou, V.; Connolly, G.N.; Behrakis, P.K. Short-term pulmonary effects of using an electronic cigarette: Impact on respiratory flow resistance, impedance, and exhaled nitric oxide. Chest 2012, 141, 1400–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, T.; Pena, I.; Temesgen, N.; Glantz, S.A. Association Between Electronic Cigarette Use and Myocardial Infarction. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhukhan, P.; Ugurlu, M.T.; Hoque, M.O. Effect of COVID-19 on Lungs: Focusing on Prospective Malignant Phenotypes. Cancers 2020, 12, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polverino, F. Cigarette Smoking and COVID-19: A Complex Interaction. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 471–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossato, M.; Russo, L.; Mazzocut, S.; Di Vincenzo, A.; Fioretto, P.; Vettor, R. Current smoking is not associated with COVID-19. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 2001290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Zeki, A.A. Does Vaping Increase Susceptibility to COVID-19? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 1055–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, D.; Shahab, L.; Brown, J.; Perski, O. The association of smoking status with SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalization and mortality from COVID-19: A living rapid evidence review with Bayesian meta-analyses (version 7). Addiction 2021, 116, 1319–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardavas, C.I.; Nikitara, K. COVID-19 and smoking: A systematic review of the evidence. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2020, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.E.; Brown, J.; Shahab, L.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. COVID-19, smoking and inequalities: A study of 53 002 adults in the UK. Tob. Control 2020, 30, e111–e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsigaris, P.; da Silva, J.A.T. Smoking Prevalence and COVID-19 in Europe. Nicotine Tob. Res. Off. J. Soc. Res. Nicotine Tob. 2020, 22, 1646–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Certain Medical Conditions and Risk for Severe COVID-19 Illness. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- WHO. Smoking and COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/smoking-and-covid-19 (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Gaiha, S.M.; Lempert, L.K.; Halpern-Felsher, B. Underage Youth and Young Adult e-Cigarette Use and Access Before and During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2027572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroel, M.A.; Cha, A.E.; Vahratian, A. Electronic Cigarette Use among U.S. Adults, 2018; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Ed.; NCHS Data Brief; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8.

- Koyama, S.; Tabuchi, T.; Okawa, S.; Kadobayashi, T.; Shirai, H.; Nakatani, T.; Miyashiro, I. Changes in Smoking Behavior Since the Declaration of the COVID-19 State of Emergency in Japan: A Cross-sectional Study From the Osaka Health App. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 31, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, R.; To, Q.G.; Khalesi, S.; Williams, S.L.; Alley, S.J.; Thwaite, T.L.; Fenning, A.S.; Vandelanotte, C. Depression, Anxiety and Stress during COVID-19: Associations with Changes in Physical Activity, Sleep, Tobacco and Alcohol Use in Australian Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Rzymski, P. Dietary Choices and Habits during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from Poland. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravely, S.; Craig, L.V.; Cummings, K.M.; Ouimet, J.; Loewen, R.; Martin, N.; Chung-Hall, J.; Driezen, P.; Hitchman, S.C.; McNeill, A.; et al. Smokers’ cognitive and behavioural reactions during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from the 2020 ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, D.B.; Al-Hamdani, M. Young Canadian e-Cigarette Users and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Examining Vaping Behaviors by Pandemic Onset and Gender. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 620748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreslake, J.M.; Simard, B.J.; O’Connor, K.M.; Patel, M.; Vallone, D.M.; Hair, E.C. E-Cigarette Use Among Youths and Young Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic: United States, 2020. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkhoran, S.; Levy, D.E.; Rigotti, N.A. Smoking and E-Cigarette Use among U.S. Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2022, 62, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.; Epperson, A.E.; Halpern-Felsher, B.; Halliday, D.M.; Song, A.V. Smokers Are More Likely to Smoke More after the COVID-19 California Lockdown Order. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HINTS 5 Cycle 4. Health Information National Trends Survey 5 (HINTS 5) Cycle 4 Methodology Report. Published Online 2020. Available online: https://hints.cancer.gov/docs/methodologyreports/HINTS5_Cycle4_MethodologyReport.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Finney Rutten, L.J.; Blake, K.D.; Skolnick, V.G.; Davis, T.; Moser, R.P.; Hesse, B.W. Data Resource Profile: The National Cancer Institute’s Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 49, 17–17j. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Wahl, I.; Rose, M.; Spitzer, C.; Glaesmer, H.; Wingenfeld, K.; Schneider, A.; Brähler, E. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: Validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 122, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 2009, 50, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. Why Stata. Available online: https://www.stata.com/why-use-stata/ (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- Yach, D. Tobacco Use Patterns in Five Countries During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020, 22, 1671–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemperer, E.M.; West, J.C.; Peasley-Miklus, C.; Villanti, A.C. Change in Tobacco and Electronic Cigarette Use and Motivation to Quit in Response to COVID-19. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020, 22, 1662–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Zyl-Smit, R.N.; Richards, G.; Leone, F.T. Tobacco smoking and COVID-19 infection. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 664–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, M.R.; Tamura, K.; Claudel, S.E.; Xu, S.; Ceasar, J.N.; Collins, B.S.; Langerman, S.; Mitchell, V.M.; Baumer, Y.; Powell-Wiley, T.M. Geospatial Analysis of Neighborhood Deprivation Index (NDI) for the United States by County. J. Maps 2020, 16, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harlow, A.F.; Stokes, A.; Brooks, D.R. Socioeconomic and Racial/Ethnic Differences in E-Cigarette Uptake Among Cigarette Smokers: Longitudinal Analysis of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 21, 1385–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelius, M.E.; Wang, T.W.; Jamal, A.; Loretan, C.G.; Neff, L.J. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1736–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, B.M.; Abraham, I. The Decline in e-Cigarette Use Among Youth in the United States-An Encouraging Trend but an Ongoing Public Health Challenge. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2112464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindelar, J.L. Regulating Vaping—Policies, Possibilities, and Perils. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walley, S.C.; Wilson, K.M.; Winickoff, J.P.; Groner, J. A Public Health Crisis: Electronic Cigarettes, Vape, and JUUL. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20182741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.; Glasser, A.M.; Abudayyeh, H.; Pearson, J.L.; Villanti, A.C. E-Cigarette Marketing and Communication: How E-Cigarette Companies Market E-Cigarettes and the Public Engages with E-cigarette Information. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 21, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syamlal, G.; Clark, K.A.; Blackley, D.J.; King, B.A. Prevalence of Electronic Cigarette Use Among Adult Workers—United States, 2017–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S.; Mistry, R.; Bazargan, M. Race, Educational Attainment, and E-Cigarette Use. J. Med. Res. Innov. 2020, 4, e000185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Markets. What You Need to Know about Smoking and Health Insurance. Available online: https://www.healthmarkets.com/content/smoking-and-health-insurance (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Center for Public Health Systems Science. Pricing Policy: A Tobacco Control Guide. Available online: https://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/tclc-guide-pricing-policy-WashU-2014.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Public Health Law Center. Taxation. Available online: https://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/topics/commercial-tobacco-control/taxation-and-product-pricing/taxation (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Truth Initiative. The Importance of Tobacco Taxes. Available online: https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/tobacco-prevention-efforts/importance-tobacco-taxes (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Logie, C. The case for the World Health Organization’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Health to address sexual orientation. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1243–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heslin, K.C.; Hall, J.E. Sexual Orientation Disparities in Risk Factors for Adverse COVID-19-Related Outcomes, by Race/Ethnicity—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2017–2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, L.S.; Reisner, S.L.; Findling, M.G.; Blendon, R.J.; Benson, J.M.; Sayde, J.M.; Miller, C. Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health Serv. Res. 2019, 54 (Suppl. S2), 1454–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, J.N.; Salerno, J.; Williams, N.D.; Rinderknecht, R.G.; Drotning, K.J.; Sayer, L.; Doan, L. Sexual Minority Disparities in Health and Well-Being as a Consequence of the COVID-19 Pandemic Differ by Sexual Identity. LGBT Health 2021, 8, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emory, K.; Buchting, F.O.; Trinidad, D.R.; Vera, L.; Emery, S.L. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) View it Differently Than Non-LGBT: Exposure to Tobacco-related Couponing, E-cigarette Advertisements, and Anti-tobacco Messages on Social and Traditional Media. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 21, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchting, F.O.; Emory, K.T.; Scout; Kim, Y.; Fagan, P.; Vera, L.E.; Emery, S. Transgender Use of Cigarettes, Cigars, and E-Cigarettes in a National Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaalema, D.E.; Pericot-Valverde, I.; Bunn, J.Y.; Villanti, A.C.; Cepeda-Benito, A.; Doogan, N.J.; Keith, D.R.; Kurti, A.N.; Lopez, A.A.; Nighbor, T.; et al. Tobacco use in cardiac patients: Perceptions, use, and changes after a recent myocardial infarction among US adults in the PATH study (2013–2015). Prev. Med. 2018, 117, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critcher, C.R.; Siegel, M. Re-examining the Association Between E-Cigarette Use and Myocardial Infarction: A Cautionary Tale. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 61, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigotti, N.A. Balancing the Benefits and Harms of E-Cigarettes: A National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine Report. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 168, 666–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall Sample | Responses before the COVID-19 Pandemic Declaration | Responses after the COVID-19 Pandemic Declaration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| 3865 (100%) | 1437 (35.31%) | 2428 (64.69%) | |

| Age | |||

| 18–25 | 147 (13.27) | 41 (10.22) | 106 (14.92) |

| 26–34 | 337 (12.93) | 110 (9.67) | 227 (14.69) |

| 35–49 | 703 (25.52) | 212 (22.71) | 491 (27.04) |

| 50–64 | 1142 (27.72) | 433 (33.01) | 709 (24.87) |

| 65 or older | 1409 (20.56) | 598 (24.39) | 811 (18.48) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 2204 (51.35) | 804 (49.00) | 1400 (52.63) |

| Male | 1561 (48.65) | 598 (51.00) | 963 (47.37) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2133 (63.35) | 904 (70.15) | 1229 (59.63) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 481 (11.14) | 135 (8.31) | 346 (12.68) |

| Hispanic | 596 (16.97) | 170 (12.81) | 426 (19.25) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 161 (5.21) | 51 (4.14) | 110 (5.80) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 119 (3.33) | 49 (4.59) | 70 (2.64) |

| Sexual identity | |||

| Heterosexual | 3402 (94.58) | 2113 (95.36) | 1289 (94.16) |

| Sexual and gender minority | 163 (5.42) | 56 (4.64) | 107 (5.84) |

| Level of education completed | |||

| Less than High School | 273 (8.03) | 90 (7.20) | 183 (8.49) |

| High School graduate | 705 (22.51) | 251 (20.23) | 454 (23.76) |

| Some college | 1081 (39.18) | 415 (39.66) | 666 (38.92) |

| College graduate or higher | 1663 (30.27) | 643 (32.90) | 1020 (28.84) |

| Total annual family income | |||

| Less than $20,000 | 624 (15.15) | 216 (14.15) | 408 (15.60) |

| $20,000 to <$35,000 | 451 (11.46) | 170 (10.85) | 281 (11.80) |

| $35,000 to <$50,000 | 460 (12.67) | 166 (12.03) | 294 (13.01) |

| $50,000 to <$75,000 | 592 (18.26) | 229 (17.47) | 363 (18.70) |

| $75,000 or more | 1321 (42.46) | 514 (45.50) | 807 (40.80) |

| Employment status | |||

| Unemployed | 1888 (40.89) | 756 (41.31) | 1132 (40.67) |

| Employed | 1890 (59.11) | 652 (58.70) | 1238 (59.33) |

| Health insurance | |||

| No | 203 (9.00) | 63 (8.21) | 140 (9.43) |

| Yes | 3604 (91.00) | 1352 (91.79) | 2252 (90.57) |

| Rural-urban commuting area | |||

| Metropolitan | 3387 (87.16) | 1217 (84.82) | 2170 (88.44) |

| Micropolitan/Small town/rural | 478 (12.84) | 220 (15.18) | 258 (11.56) |

| U.S. Census region | |||

| Northeast | 581 (17.54) | 225 (18.03) | 356 (17.28) |

| Midwest | 645 (20.83) | 251 (21.81) | 394 (20.30) |

| South | 1728 (37.92) | 634 (36.67) | 1094 (38.61) |

| West | 911 (23.71) | 584 (23.50) | 327 (23.82) |

| Number of adult household members | |||

| At least two persons | 2509 (79.00) | 938 (80.50) | 1571 (78.19) |

| Less than two persons | 1356 (21.00) | 499 (19.50) | 857 (21.81) |

| General health status | |||

| Excellent/very good/good | 3192 (85.89) | 1200 (86.70) | 1992 (85.45) |

| Fair or poor | 627 (14.11) | 221 (13.30) | 406 (14.55) |

| Current anxiety/depression status | |||

| None | 2670 (68.57) | 1003 (70.03) | 1667 (67.78) |

| Mild | 629 (17.48) | 246 (17.97) | 383 (17.21) |

| Moderate | 258 (7.93) | 76 (6.44) | 182 (8.75) |

| Severe | 173 (6.02) | 65 (5.56) | 108 (6.27) |

| BMI (Mean, SD) | 28.42 (6.71) | 28.18 (6.43) | 28.54 (6.84) |

| Moderate physical activity intensity | |||

| None | 1048 (27.11) | 392 (28.93) | 656 (26.12) |

| At least one day per week | 2750 (72.89) | 1729 (71.07) | 1021 (73.88) |

| CVD Condition status | |||

| None | 3395 (91.88) | 1247 (90.97) | 2148 (92.38) |

| Yes | 407 (8.12) | 172 (9.03) | 235 (7.62) |

| Current e-cigarette use status | |||

| Never user | 3314 (92.70) | 1245 (95.21) | 2069 (91.37) |

| Current user | 114 (7.30) | 40 (4.79) | 74 (8.63) |

| Model 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | |

| Age | ||

| 35–49 | Ref | |

| 18–25 | 7.58 *** | (2.96, 19.44) |

| 26–34 | 2.36 | (0.93, 5.97) |

| 50–64 | 0.55 | (0.242, 1.25) |

| 65+ | 0.19 ** | (0.06, 0.62) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | Ref | |

| Male | 1.17 | (0.63, 2.19) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.14 * | (0.03, 0.79) |

| Hispanic | 0.13 *** | (0.05, 0.38) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.66 | (0.17, 2.48) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 0.45 | (0.09, 2.36) |

| Sexual identity | ||

| Heterosexual | Ref | |

| Sexual and gender minority | 3.58 ** | (1.32, 9.73) |

| Level of education completed | ||

| High School graduate | Ref | |

| Less than High School | 1.95 | (0.51, 7.50) |

| Some college | 0.89 | (0.40, 1.98) |

| College graduate or higher | 0.33 * | (0.14, 0.79) |

| Total family annual income | ||

| $50,000 to <$75,000 | Ref | |

| Less than $20,000 | 0.36 | (0.12, 1.07) |

| $20,000 to <$35,000 | 0.87 | (0.33, 2.30) |

| $35,000 to <$50,000 | 0.74 | (0.26, 2.09) |

| $75,000 or more | 0.67 | (0.32, 1.38) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | Ref | |

| Unemployed | 0.8 | (0.38, 1.68) |

| Health insurance | ||

| Yes | Ref | |

| No | 3.23 * | (1.20, 8.66) |

| Rural-urban commuting area | ||

| Metropolitan | Ref | |

| Micropolitan/Small town/rural | 1.12 | (0.44, 2.88) |

| U.S. Census region | ||

| South | Ref | |

| Northeast | 0.82 | (0.32, 2.09) |

| Midwest | 0.78 | (0.26, 2.31) |

| West | 1.61 | (0.71, 3.63) |

| Number of adult household members | ||

| At least two persons | Ref | |

| Less than two persons | 1.21 | (0.69, 2.13) |

| General health status | ||

| Excellent/very good/good | Ref | |

| Fair or poor | 0.91 | (0.35, 2.41) |

| Current anxiety/depression status | ||

| None | Ref | |

| Mild | 1.61 | (0.69, 3.72) |

| Moderate | 1.49 | (0.60, 3.69) |

| Severe | 1.66 | (0.46, 5.94) |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 0.97 | (0.93, 1.02) |

| Moderate physical activity intensity | ||

| At least one day per week | Ref | |

| None | 1.08 | (0.55, 2.11) |

| CVD Condition status | ||

| None | Ref | |

| Yes | 1.85 | (0.66, 5.16) |

| COVID-19 pandemic declaration | ||

| Responses before the declaration | Ref | |

| Responses after the declaration | 1.13 | (0.56, 2.30) |

| Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |

| Age | ||||

| 35–49 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 18–25 | 4.63 | (0.77, 27.74) | 9.91 *** | (3.29, 29.86) |

| 26–34 | 0.84 | (0.20, 3.47) | 3.67 * | (1.08, 12.45) |

| 50–64 | 0.31 * | (0.10, 0.91) | 0.58 | (0.21, 1.64) |

| 65+ | 0.01 *** | (0.01, 0.09) | 0.24 | (0.05, 1.22) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Ref | Ref | ||

| Male | 0.69 | (0.25, 1.92) | 1.59 | (0.77, 3.29) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.22 | (0.05, 1.02) | 0.05 * | (0.01, 0.69) |

| Hispanic | 0.28 | (0.06, 1.30) | 0.12 ** | (0.03, 0.47) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 2.12 | (0.48, 9.36) | 0.15 | (0.02, 1.49) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 2.48 | (0.28, 21.73) | 0.21 | (0.03, 1.44) |

| Sexual identity | ||||

| Heterosexual | Ref | Ref | ||

| Sexual and gender minority | 4.54 | (0.88, 23.25) | 3.51 * | (1.10, 11.16) |

| Level of education completed | ||||

| High School graduate | Ref | Ref | ||

| Less than High School | 2.04 | (0.50, 8.37) | 2.04 | (0.43, 9.73) |

| Some college | 0.73 | (0.25, 2.14) | 0.99 | (0.41, 2.38) |

| College graduate or higher | 0.62 | (0.15, 2.57) | 0.29 * | (0.09, 0.97) |

| Total family annual income | ||||

| $50,000 to <$75,000 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 2.53 | (0.52, 12.37) | 0.20 * | (0.05, 0.84) |

| $20,000 to <$35,000 | 3.07 | (0.59, 15.92) | 0.5 | (0.13, 1.82) |

| $35,000 to <$50,000 | 3.45 | (0.47, 25.55) | 0.42 | (0.13, 1.33) |

| $75,000 or more | 0.6 | (0.17, 2.16) | 0.64 | (0.27, 1.49) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | Ref | Ref | ||

| Unemployed | 0.41 | (0.10, 1.65) | 0.82 | (0.36, 1.87) |

| Health insurance | ||||

| Yes | Ref | Ref | ||

| No | 1.27 | (0.14, 11.21) | 4.57 * | (1.42, 14.67) |

| Rural-urban commuting area | ||||

| Metropolitan | Ref | Ref | ||

| Micropolitan/Small town/rural | 0.20 * | (0.04, 0.99) | 2.34 | (0.85, 6.43) |

| US Census region | ||||

| South | Ref | Ref | ||

| Northeast | 1.06 | (0.40, 2.80) | 0.41 | (0.12, 1.37) |

| Midwest | 0.87 | (0.18, 4.31) | 0.67 | (0.18, 2.43) |

| West | 0.45 | (0.09, 2.20) | 2.08 | (0.79, 5.46) |

| Number of adult household members | ||||

| At least two persons | Ref | Ref | ||

| Less than two persons | 0.35 | (0.06, 1.92) | 1.81 | (0.87, 3.75) |

| General health status | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good | Ref | Ref | ||

| Fair or poor | 0.77 | (0.07, 8.84) | 0.86 | (0.30, 2.48) |

| Current anxiety/depression status | ||||

| None | Ref | Ref | ||

| Mild | 1.36 | (0.30, 6.12) | 1.9 | (0.66, 5.42) |

| Moderate | 0.4 | (0.05, 2.97) | 2.16 | (0.80, 5.85) |

| Severe | 1.1 | (0.12, 9.95) | 2.27 | (0.50, 10.38) |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 0.99 | (0.93, 1.07) | 0.95 * | (0.90, 0.99) |

| Moderate physical activity intensity | ||||

| At least one day per week | Ref | Ref | ||

| None | 2.11 | (0.84, 5.31) | 0.85 | (0.33, 2.18) |

| CVD Condition status | ||||

| None | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.18 | (0.01, 3.33) | 4.71 *** | (1.88, 11.81) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mamudu, H.M.; Adzrago, D.; Dada, O.; Odame, E.A.; Ahuja, M.; Awasthi, M.; Weierbach, F.M.; Williams, F.; Stewart, D.W.; Paul, T.K. Examining Disparities in Current E-Cigarette Use among U.S. Adults before and after the WHO Declaration of the COVID-19 Pandemic in March 2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095649

Mamudu HM, Adzrago D, Dada O, Odame EA, Ahuja M, Awasthi M, Weierbach FM, Williams F, Stewart DW, Paul TK. Examining Disparities in Current E-Cigarette Use among U.S. Adults before and after the WHO Declaration of the COVID-19 Pandemic in March 2020. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(9):5649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095649

Chicago/Turabian StyleMamudu, Hadii M., David Adzrago, Oluwabunmi Dada, Emmanuel A. Odame, Manik Ahuja, Manul Awasthi, Florence M. Weierbach, Faustine Williams, David W. Stewart, and Timir K. Paul. 2023. "Examining Disparities in Current E-Cigarette Use among U.S. Adults before and after the WHO Declaration of the COVID-19 Pandemic in March 2020" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 9: 5649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095649

APA StyleMamudu, H. M., Adzrago, D., Dada, O., Odame, E. A., Ahuja, M., Awasthi, M., Weierbach, F. M., Williams, F., Stewart, D. W., & Paul, T. K. (2023). Examining Disparities in Current E-Cigarette Use among U.S. Adults before and after the WHO Declaration of the COVID-19 Pandemic in March 2020. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(9), 5649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20095649