Dissemination and Implementation of a Text Messaging Campaign to Improve Health Disparities among Im/Migrant Workers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Text Messaging in Health Promotion

1.2. Occupational Health and Safety Promotion and Commercial Fishermen

2. Materials and Methods

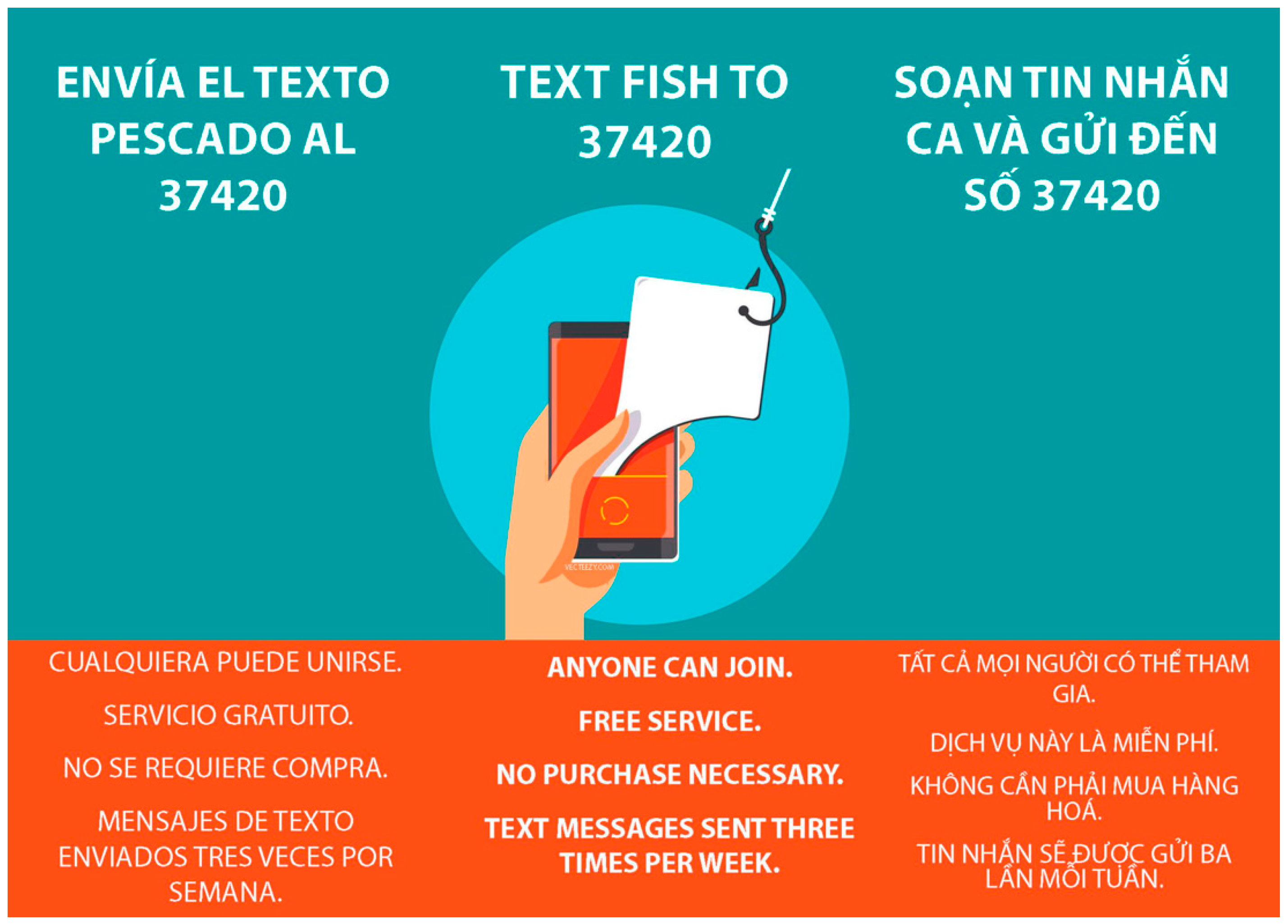

2.1. Text Messaging Campaign Design

2.2. Text Messaging Campaign Implementation

2.3. Text Message Design

2.4. Participants

3. Results

3.1. Trilingual Digital Communications and Navigating Federal Regulations

3.2. Technical Barriers

3.3. Generational Digital Skills

3.4. Migratory Considerations

3.5. Timing of Messages

4. Discussion

4.1. Short-Term Recommendations

4.2. Long-Term Policy Recommendations

4.2.1. Equitable Trainings

4.2.2. Equitable Health Care Options

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Congress. Magnuson–Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act; Public Law 94-265; U.S. Government: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 1801–1884.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Additional Actions Needed to Improve Commercial Fishing Vessel Safety Efforts; U.S. Government Accountability Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; p. 64.

- Marine Transportation. CDC—NIOSH Program Portfolio: Center for Maritime Safety and Health Studies. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/programs/cmshs/default.html (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Myers, M.L.; Durborow, R.M.; Kane, A.S. Gulf of Mexico Seafood Harvesters: Part 1. Occupational Injury and Fatigue Risk Factors. Safety 2018, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, S.L.; Lincoln, J.M.; Lucas, D.L. Fatal Falls Overboard in Commercial Fishing—United States, 2000–2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gander, P.; Berg, M.V.D.; Signal, L. Sleep and Sleepiness of Fishermen on Rotating Schedules. Chronobiol. Int. 2008, 25, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doza, S.; Bovbjerg, V.E.; Vaughan, A.; Nahorniak, J.S.; Case, S.; Kincl, L.D. Health-Related Exposures and Conditions among US Fishermen. J. Agromed. 2021, 27, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, S.W.; Kucera, K.; Loomis, D.; McDonald, M.A.; Lipscomb, H.J. Work related injuries in small scale commercial fishing. Inj. Prev. 2004, 10, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, C.; Baker, T.; Cherry, D. Chronic Health Risks in Commercial Fishermen: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from a Small Rural Fishing Village in Alaska. J. Agromed. 2018, 23, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot-Wright, S.; Cherryhomes, E.; Davis, L. The impact of economic deregulation for health disparities among Gulf of Mexico commercial fishermen. Mar. Policy 2022, 141, 105099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, M.; Rodríguez-Guzmán, J.; Watson, J.; van Wendel de Joode, B.; Mergler, D.; da Silva, A.S. Worker health and safety and climate change in the Americas: Issues and research needs. Rev. Panam Salud Publ. 2016, 40, 192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Guerin, R.J.; Harden, S.M.; Rabin, B.A.; Rohlman, D.S.; Cunningham, T.R.; TePoel, M.R.; Parish, M.; Glasgow, R.E. Dissemination and Implementation Science Approaches for Occupational Safety and Health Research: Implications for Advancing Total Worker Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J.L.; Gilmore, K.; Shepherd, S.; Bs, A.W.; Carruth, A.; Nalbone, J.T.; Aa, G.G.; Nonnenmann, M. Factors Influencing Safety Among a Group of Commercial Fishermen Along the Texas Gulf Coast. J. Agromed. 2010, 15, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, K.J.; Noar, S.M.; Iannarino, N.T.; Harrington, N.G. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: A meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 97, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot-Wright, S.; Farr, N.M.; Cherryhomes, E. A community-led mobile health clinic to improve structural and social determinants of health among (im)migrant workers. Int. J. Equity Health 2022, 21, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIA. Country Comparisons Telephones—Mobile Cellulare. 2022. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/telephones-mobile-cellular/country-comparison (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Neville, R.; Greene, A.G.; McLeod, J.; Tracy, A.; Surie, J. Mobile phone text messaging can help young people manage asthma. BMJ 2002, 325, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, M.L.M.; Rodriguez, K.M.M.; Fehmie, D.A.M.; Mojtabai, R.M.; Cullen, B.M. Acceptability of Texting 4 Relapse Prevention, Text Messaging-Based Relapse Prevention Program for People With Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective Disorder. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2021, 210, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, M.O.; Krantz, M.J.; Albright, K.; Beaty, B.; Coronel-Mockler, S.; Bull, S.; Estacio, R.O. A controlled trial of mobile short message service among participants in a rural cardiovascular disease prevention program. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 13, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, C.A.; Sparling, A.; Hardeman, G.; de Hernandez, B.U.; Pasupuleti, N.; Carr, J.; Coltman, K.; Neuwirth, Z. Development, Implementation, and Results from a COVID-19 Messaging Campaign to Promote Health Care Seeking Behaviors Among Community Clinic Patients. J. Community Health 2020, 46, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.D.; Wallace, J.L.; Snider, J. Pilot evaluation of the text4baby mobile health program. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.; McCright, J.; Dobkin, L.; Woodruff, A.J.; Klausner, J.D. SEXINFO: A Sexual Health Text Messaging Service for San Francisco Youth. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.; Aldoory, L.; Garza, M.A.; Fryer, C.S.; Sawyer, R.; Holt, C.L. A Spiritually-Based Text Messaging Program to Increase Cervical Cancer Awareness Among African American Women: Design and Development of the CervixCheck Pilot Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2018, 2, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot-Wright, S.P.; Lu, Y.; Torres, E.D.; Le, V.D.; Hall, H.R.; Temple, J.R. Design and Feasibility of a School-Based Text Message Campaign to Promote Healthy Relationships. Sch. Ment. Health 2018, 10, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready. Emergency Alerts. 2022. Available online: https://www.ready.gov/alerts#:~:text=WirelessEmergencyAlerts(WEAs)&text=WEAslookliketextmessages,theagencyissuingthealert (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Levin, J.L.; Gilmore, K.; Wickman, A.; Shepherd, S.; Shipp, E.; Nonnenmann, M.; Carruth, A. Workplace Safety Interventions for Commercial Fishermen of the Gulf. J. Agromed. 2016, 21, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorvaldsen, T.; Kaustell, K.O.; Mattila, T.E.; Høvdanum, A.; Christiansen, J.M.; Hovmand, S.; Snorrason, H.; Tomasson, K.; Holmen, I.M. What works? Results of a Nordic survey on fishers’ perceptions of safety measures. Mar. Policy 2018, 95, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siame, S.; Bygvraa, D.A.; Jensen, O.C. Facilitators and barriers to implementing occupational safety interventions in the fishing industry: A scoping review. Saf. Sci. 2021, 145, 105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruth, A.K.; Levin, J.L.; Gilmore, K.; Bui, T.; Aa, G.G.; Evert, W.; Sealey, L. Cultural Influences on Safety and Health Education Among Vietnamese Fishermen. J. Agromed. 2010, 15, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIOSH. Commercial Fishing Safety: Health Communication Solutions. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/fishing/healthcomm.html (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Dugan, A.G.; Punnett, L. Dissemination and Implementation Research for Occupational Safety and Health. Occup. Health Sci. 2017, 1, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, I.; Kite-Powell, H. Safety at sea and fisheries management: Fishermen’s attitudes and the need for co-management. Mar. Policy 2000, 24, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.E.; Hoor, G.A.T.; Van Lieshout, S.; Rodriguez, S.A.; Beidas, R.S.; Parcel, G.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Markham, C.M.; Kok, G. Implementation Mapping: Using Intervention Mapping to Develop Implementation Strategies. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farbenblum, B.; Berg, L.; Kintominas, A. Transformative Technology for Migrant Workers—Opportunities, Challenges, and Risks. 2018. Available online: https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/publications/transformative-technology-migrant-workers-opportunities-challenges-and-risks (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Rhee, K.; Dankwa-Mullan, I.; Brennan, V.; Clark, C. What is TechQuity? J. Heath Care Poor Underserved 2021, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Commercial Guard. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Fishing Vessel Safety Division (CG-CVC-3). 2022. Available online: https://www.dco.uscg.mil/Our-Organization/Assistant-Commandant-for-Prevention-Policy-CG-5P/Inspections-Compliance-CG-5PC-/Commercial-Vessel-Compliance/Fishing-Vessel-Safety-Division/CVC-3-Home-Page/ (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- NIOSH. Commercial Fishing Safety. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/fishing/default.html (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Herbers, J. U.S. Seamen’s hospitals still open in many cities. The New York Times, 27 October 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, Z.; Grader, Z. Health Care, Finally! The Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, D.; Lyons, B.; Edwards, J. Medicaid: Health Care for the Poor in the Reagan Era. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1988, 9, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J.; Taylor, J.; Krapels, J.; Sutherland, A.; Felician, M.F.; Liu, J.L.; Davis, L.M.; Rohr, C. Are Better Health Outcomes Related to Social Expenditure? A Cross-National Empirical Analysis of Social Expenditure and Population Health Measures; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Knowledge | Prevention | Resource-Based | |

| Message Content | Fact, explanation, or contained information | Information to protect oneself, community, or property | Advice and assisted people in locating resources |

| Example of an Initial message | ‘In preparation for a hurricane, assemble a Go-Kit with items you cannot do without during an emergency. For an example of a Go-kit, reply MORE.’ | ‘If you are going to move your boat prior to a hurricane, determine a safe place to go and how long it will take for you to get there ahead of time.’ | ‘Learn your docks Harbor of Safe Refugee Policy. In the event of a hurricane have a plan for where you can more your vessel. Reply MORE for details.’ |

| Example of a response Message | ‘Your kit should include water, nonperishable food, flashlights, a radio, first aid kid, batteries, whistle duct tape and moist towelettes’ | ‘Check with your dock manager for their policy for hurricanes. Violating the safety zone could result in a fine.’ | ‘Contact the Texas Sea Grant Program for a more specific program for what you can do in a hurricane’ with contact information included. |

| Implementation Predictors | |

|---|---|

| Structural factors | Federal Regulations |

| Innovation factors | Technical Barriers |

| End user factors | Generational Digital Skills, Cell Phone Ownership |

| Organizational factors | Migratory Considerations |

| Implementer factors | Timing of Messages |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cherryhomes, E.; Guillot-Wright, S. Dissemination and Implementation of a Text Messaging Campaign to Improve Health Disparities among Im/Migrant Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5311. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075311

Cherryhomes E, Guillot-Wright S. Dissemination and Implementation of a Text Messaging Campaign to Improve Health Disparities among Im/Migrant Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(7):5311. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075311

Chicago/Turabian StyleCherryhomes, Ellie, and Shannon Guillot-Wright. 2023. "Dissemination and Implementation of a Text Messaging Campaign to Improve Health Disparities among Im/Migrant Workers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 7: 5311. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075311

APA StyleCherryhomes, E., & Guillot-Wright, S. (2023). Dissemination and Implementation of a Text Messaging Campaign to Improve Health Disparities among Im/Migrant Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(7), 5311. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075311