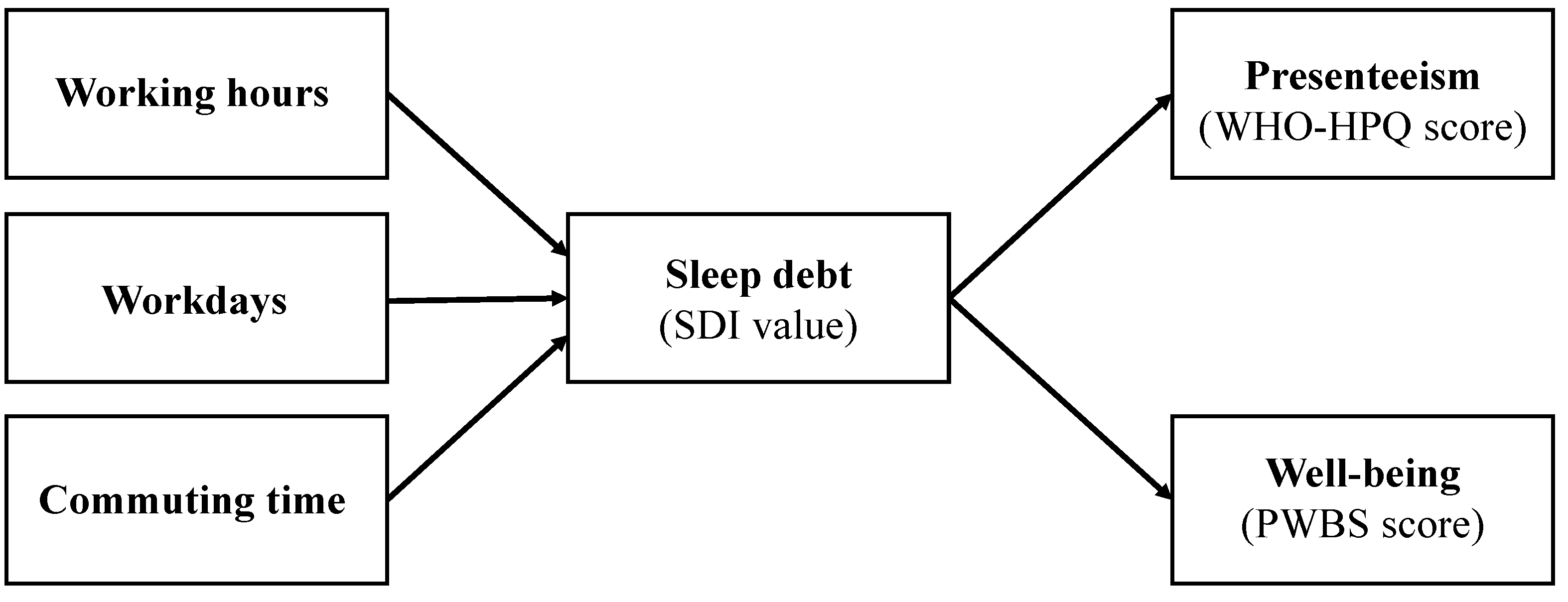

Sleep Debt Mediates the Relationship between Work-Related Social Factors, Presenteeism, and Well-Being in Japanese Workers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

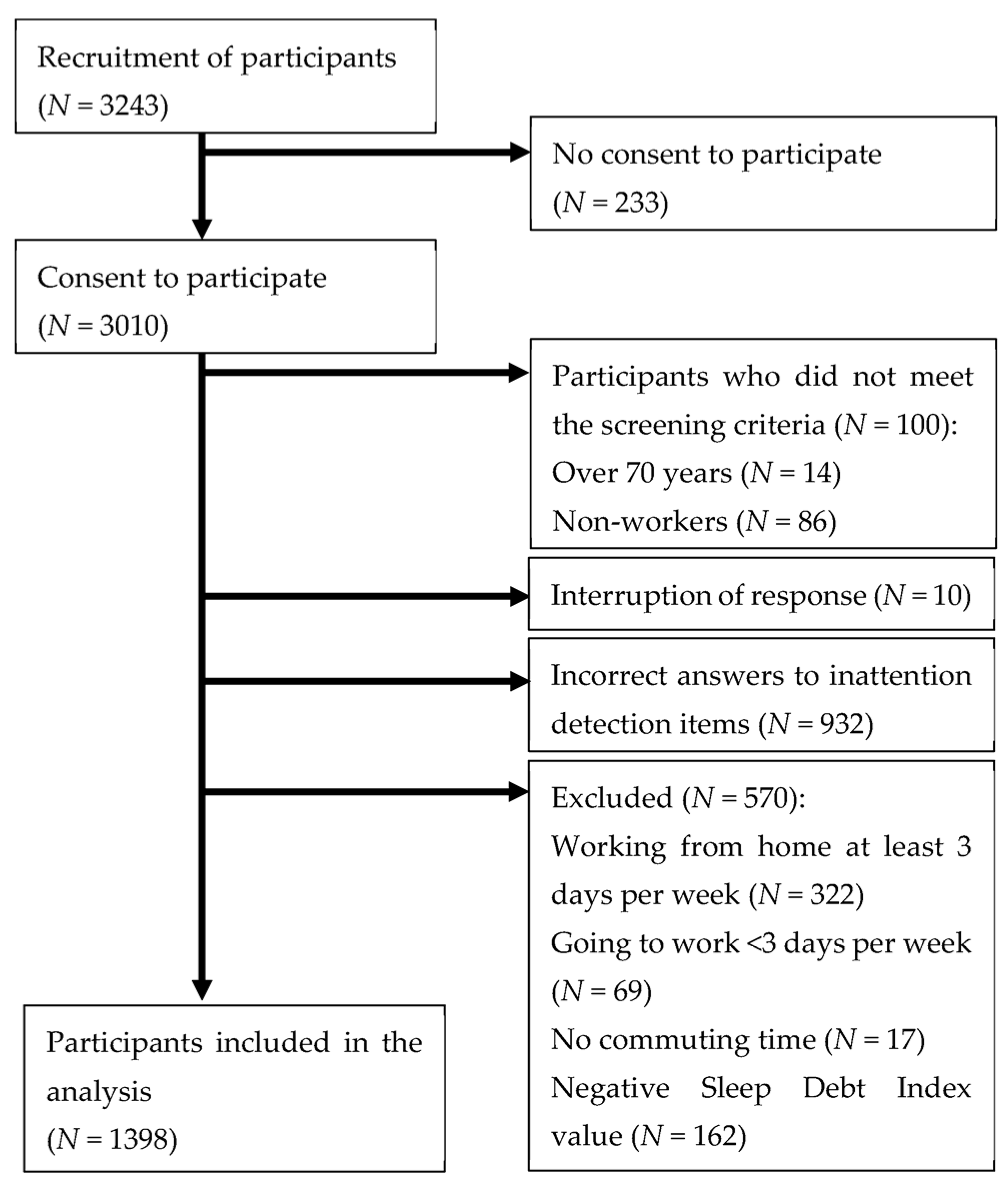

2.1. Procedures and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burton, W.N.; Pransky, G.; Conti, D.J.; Chen, C.Y.; Edington, D.W. The association of medical conditions and presenteeism. J Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 46, S38–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, W.N.; Chen, C.Y.; Schultz, A.B.; Li, X. Association between employee sleep with workplace health and economic outcomes. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guertler, D.; Vandelanotte, C.; Short, C.; Alley, S.; Schoeppe, S.; Duncan, M.J. The association between physical activity, sitting time, sleep duration, and sleep quality as correlates of presenteeism. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 57, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Xie, Y.; Zou, X. Association between sleep duration and depression in US adults: A cross-sectional study. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 296, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okajima, I.; Komada, Y.; Ito, W.; Inoue, Y. Sleep debt and social jetlag associated with sleepiness, mood, and work performance among workers in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, Y.; Ibata, R.; Nakano, N.; Sakano, Y. Impact of sleep debt, social jetlag, and insomnia symptoms on presenteeism and psychological distress of workers in Japan: A cross-sectional study. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2022, 16, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basner, M.; Fomberstein, K.M.; Razavi, F.M.; Banks, S.; William, J.H.; Rosa, R.R.; Dinges, D.F. American Time Use Survey: Sleep time and its relationship to waking activities. Sleep 2007, 30, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsu, T.; Kaneita, Y.; Aritake, S.; Mishima, K.; Uchiyama, M.; Akashiba, T.; Uchimura, N.; Nakaji, S.; Munezawa, T.; Kokaze, A.; et al. A cross-sectional study of the association between working hours and sleep duration among the Japanese working population. J. Occup. Health 2013, 55, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; He, J.; Ouyang, F.; Luo, D.; Xiao, S. Long working hours, work-related stressors and sleep disturbances among Chinese government employees: A large population-based follow-up study. Sleep Med. 2022, 96, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, M.E.; Weng, J.; Reid, K.J.; Wang, R.; Ramos, A.R.; Wallace, D.M.; Alcantara, C.; Cai, J.; Perreira, K.; Espinoza Giacinto, R.A.; et al. Commuting and sleep: Results from the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos Sueño Ancillary Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 54, e49–e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, T.J. Trade-offs between commuting time and health-related activities. J. Urban Health. 2012, 89, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okajima, I.; Akitomi, J.; Murakami, H.; Tanizawa, N.; Kajiyama, I. Sleep changes during COVID-19: A study with sleep recording app users. Jpn. J. Behav. Cogn. Ther. 2021, 47, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roitblat, Y.; Burger, J.; Leit, A.; Nehuliaieva, L.; Umarova, G.S.; Kaliberdenko, V.; Kulanthaivel, S.; Buchris, N.; Shterenshis, M. Stay-at-home circumstances do not produce sleep disorders: An international survey during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 139, 110282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishimaru, T.; Fujino, Y. Association between work style and presenteeism in the Japanese service sector. J. Occup. Health 2021, 63, e12211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Bureau of Japan. In Labor Force Survey. 2021, Volume 2022. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/data/roudou/sokuhou/nen/ft/index.htm (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Maniaci, M.R.; Rogge, R.D. Caring about carelessness: Participant inattention and its effects on research. J. Res. Pers. 2014, 48, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications 2009. Japan Standard Occupational Classification Structure and Explanatory Notes. 2021. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/english/dgpp_ss/seido/shokgyou/co09-4.htm (accessed on 5 December 2009).

- Harvard Medical School. The World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire. Translated Versions of the HPQ Survey: HPQ Short Form (Japanese). 2013. Available online: https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/hpq/ftpdir/WMHJ-HPQ-SF_2018.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Kessler, R.C.; Barber, C.; Beck, A.; Berglund, P.; Cleary, P.D.; McKenas, D.; Pronk, N.; Simon, G.; Stang, P.; Ustun, T.B.; et al. The World Health Organization health and work performance questionnaire (HPQ). J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 45, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Miyaki, K.; Sasaki, Y.; Song, Y.; Tsutsumi, A.; Kawakami, N.; Shimazu, A.; Takahashi, M.; Inoue, A.; Kurioka, S.; et al. Optimal Cutoff values of WHO-HPQ presenteeism scores by ROC analysis for preventing mental sickness absence in Japanese prospective cohort. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwano, S.; Shinkawa, H.; Aoki, S.; Monden, R.; Horiuchi, S.; Sakano, Y. Development of a brief Psychological Well-Being Scale. Behav. Sci. Res. 2015, 54, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M.R. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Smithies, T.D.; Toth, A.J.; Dunican, I.C.; Caldwell, J.A.; Kowal, M.; Campbell, M.J. The effect of sleep restriction on cognitive performance in elite cognitive performers: A systematic review. Sleep 2021, 44, zsab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHill, A.W.; Hull, J.T.; Cohen, D.A.; Wang, W.; Czeisler, C.A.; Klerman, E.B. Chronic sleep restriction greatly magnifies performance decrements immediately after awakening. Sleep 2019, 42, zsz032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dongen, H.P.A.; Maislin, G.; Mullington, J.M.; Dinges, D.F. The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: Dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep 2003, 26, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaso, C.C.; Johnson, A.B.; Nelson, T.D. The effect of sleep deprivation and restriction on mood, emotion, and emotion regulation: Three meta-analyses in one. Sleep 2021, 44, zsaa289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempesta, D.; Salfi, F.; De Gennaro, L.D.; Ferrara, M. The impact of five nights of sleep restriction on emotional reactivity. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 29, e13022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M.; Ferrie, J.E.; Gimeno, D.; Vahtera, J.; Elovainio, M.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Marmot, M.G.; Kivimäki, M. Long working hours and sleep disturbances: The Whitehall II Prospective Cohort Study. Sleep 2009, 32, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, Y.; Iwano, S.; Aoki, S.; Nakano, N.; Sakano, Y. A systematic review of the effect of sleep interventions on presenteeism. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2021, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, H.; Kubo, T.; Sasaki, T.; Nishimura, Y.; Liu, X.; Matsuo, T.; So, R.; Matsumoto, S.; Takahashi, M. Prospective changes in sleep problems in response to the daily rest period among Japanese daytime workers: A longitudinal web survey. J. Sleep Res. 2022, 31, e13449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Pulakka, A.; Hanson, L.L.M.; Westerlund, H.; Halonen, J.I. Commuting distance and behavior-related health: A longitudinal study. Prev. Med. 2021, 150, 10665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Who Chooses Part-Time Work and Why? Available online: https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2018/article/who-Chooses-part-time-work-and-why.htm (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Martin, A.; Goryakin, Y.; Suhrcke, M. Does active commuting improve psychological wellbeing? Longitudinal evidence from eighteen waves of the British Household Panel Survey. Prev. Med. 2014, 69, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All Workers (N = 1398) | Full-Time Workers (N = 872) | Part-Time Workers (N = 526) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 660 (47.2) | 347 (39.8) | 384 (73.0) |

| Female | 731 (52.3) | 520 (59.6) | 140 (26.6) |

| Other | 7 (0.5) | 5 (0.6) | 2 (0.4) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 641 (45.9) | 407 (46.7) | 234 (44.5) |

| Married | 757 (54.1) | 465 (53.3) | 292 (55.5) |

| Occupation, n (%) | |||

| Administrative and managerial | 101 (7.2) | 98 (11.2) | 3 (0.6) |

| Professional and engineering | 266 (19.0) | 217 (24.9) | 49 (9.3) |

| Clerical | 379 (27.1) | 261(29.9) | 118 (22.4) |

| Sales | 112 (8.0) | 46 (5.3) | 66 (12.5) |

| Service | 210 (15.0) | 91 (10.4) | 119 (22.6) |

| Security | 16 (1.1) | 14 (1.6) | 2 (0.4) |

| Agriculture, forestry, and fishery | 12 (0.9) | 5 (0.6) | 7 (1.3) |

| Manufacturing process | 107 (7.7) | 63 (7.2) | 44 (8.4) |

| Transport and machine operation | 25 (1.8) | 17 (1.9) | 8 (1.5) |

| Construction and mining | 18 (1.3) | 16 (1.8) | 2 (0.4) |

| Carrying, cleaning, and packaging | 47 (3.4) | 9 (1.0) | 38 (7.2) |

| Workers not classified by occupation | 105 (7.5) | 35 (4.0) | 70 (13.3) |

| All Workers (N = 1398) | Full-Time Workers (N = 872) | Part-Time Workers (N = 526) | Hedges’ g [95% CI] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Age (years) | 46.09 | 12.72 | 44.65 | 12.37 | 48.47 | 12.93 | −0.30 [−0.41, −0.19] |

| Workdays per week | 4.92 | 0.70 | 5.15 | 0.48 | 4.56 | 0.83 | 0.93 [0.82, 1.04] |

| Working hours per week (h) | 29.68 | 13.66 | 34.44 | 16.47 | 21.78 | 13.66 | 0.82 [0.71, 0.93] |

| Commuting time per week (h) | 4.87 | 4.14 | 5.62 | 4.35 | 3.62 | 3.41 | 0.50 [0.39, 0.61] |

| SDI (h) | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.01 | 1.11 | 0.09 [−0.02, 0.20] |

| WHO-HPQ score | 59.94 | 18.82 | 59.07 | 18.35 | 61.37 | 19.50 | −0.12 [−0.23, −0.01] |

| PWBS score | 89.52 | 16.44 | 90.32 | 15.99 | 88.18 | 17.10 | 0.13 [0.02, 0.24] |

| Worktime | Workday | Commuting Time | Sleep Debt | Presenteeism | Well-Being | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worktime | 1 | 0.20 [0.14, 0.26] | 0.05 [−0.01, 0.12] | 0.01 [−0.06, 0.07] | −0.05 [−0.11, 0.02] | −0.02 [−0.09, 0.05] |

| Workday | 0.31 [0.23, 0.38] | 1 | −0.02 [−0.08, 0.05] | 0.04 [−0.03, 0.10] | −0.01 [−0.07, 0.06] | 0.00 [−0.07, 0.07] |

| Commuting time | 0.18 [0.10, 0.26] | 0.24 [0.16, 0.32] | 1 | 0.09 [0.02, 0.15] | −0.05 [−0.12, 0.01] | −0.04 [−0.11, 0.03] |

| Sleep debt | 0.02 [−0.07, 0.11] | 0.11 [0.02, 0.19] | 0.07 [−0.02, 0.15] | 1 | −0.17 [−0.23, −0.11] | −0.14 [−0.20, −0.07] |

| Presenteeism | −0.10 [−0.18, −0.01] | −0.09 [−0.17, 0.00] | −0.08 [−0.16, 0.01] | −0.16 [−0.24, −0.08] | 1 | 0.41 [0.35, 0.46] |

| Well-being | −0.16 [−0.24, −0.08] | −0.05 [−0.13, 0.04] | −0.03 [−0.12, 0.06] | −0.15 [−0.24, −0.07] | 0.46 [0.39, 0.53] | 1 |

| Worktime | → | Sleep Debt | Sleep Debt → Presenteeism | Sleep Debt → Well-Being | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workday | → | Sleep Debt | |||||||

| Commuting Time | → | Sleep Debt | |||||||

| Group | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |||

| All workers | −0.001 | 0.002 | −0.013 | −2.954 | 0.461 | −0.169 *** | −2.133 | 0.405 | −0.140 *** |

| 0.111 | 0.044 | 0.072 ** | |||||||

| 0.020 | 0.007 | 0.077 ** | |||||||

| Full-time workers | −0.000 | 0.002 | −0.006 | −2.980 | 0.581 | −0.171 *** | −2.051 | 0.509 | −0.135 *** |

| 0.082 | 0.075 | 0.038 | |||||||

| 0.022 | 0.008 | 0.090 ** | |||||||

| Part-time workers | −0.002 | 0.004 | −0.020 | −2.817 | 0.758 | −0.160 *** | −2.369 | 0.665 | −0.153 *** |

| 0.136 | 0.062 | 0.102 * | |||||||

| 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.045 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Takano, Y.; Iwano, S.; Ando, T.; Okajima, I. Sleep Debt Mediates the Relationship between Work-Related Social Factors, Presenteeism, and Well-Being in Japanese Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5310. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075310

Takano Y, Iwano S, Ando T, Okajima I. Sleep Debt Mediates the Relationship between Work-Related Social Factors, Presenteeism, and Well-Being in Japanese Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(7):5310. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075310

Chicago/Turabian StyleTakano, Yuta, Suguru Iwano, Takeshi Ando, and Isa Okajima. 2023. "Sleep Debt Mediates the Relationship between Work-Related Social Factors, Presenteeism, and Well-Being in Japanese Workers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 7: 5310. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075310

APA StyleTakano, Y., Iwano, S., Ando, T., & Okajima, I. (2023). Sleep Debt Mediates the Relationship between Work-Related Social Factors, Presenteeism, and Well-Being in Japanese Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(7), 5310. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075310