The Role of Emotional Responses in the VR Exhibition Continued Usage Intention: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis

2.1. Experience Economy Theory

2.2. The Impact of Escapist Experience on Continued Usage Intention

2.3. The Impact of Aesthetic Experience on Continued Usage Intention

2.4. The Mediating Impact of Presence

2.5. Moderating Role of Emotional Responses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Variable Measurement

3.2.1. Escapist Experience

3.2.2. Aesthetic Experience

3.2.3. Presence

3.2.4. Emotional Responses

3.2.5. Continued Usage Intention

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

Descriptive Statistics

5. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Items | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escapist experience | EE1 | Do you have a feeling of being in another place while experiencing the VR exhibition? | [59,60,61] |

| EE2 | In the process of experiencing the VR exhibition, there is a feeling of being out of touch with reality. | ||

| EE3 | Forgetting time while experiencing VR exhibition. | ||

| EE4 | In the process of experiencing the VR exhibition, there is a sense of being at different times. | ||

| EE5 | During the visit to the VR exhibition, you can temporarily forget about your daily life. | ||

| EE6 | During the visit to the VR exhibition, it was like stepping back in time. | ||

| EE7 | During the visit to the exhibition, the mood shifted. | ||

| EE8 | It feels like experiencing a new virtual world. | ||

| EE9 | In the process of virtual space experience, it feels like becoming another person. | ||

| EE10 | During the tour of the exhibition, I did not know that time was passing. | ||

| EE11 | During the VR exhibition experience, it felt different from your usual self. | ||

| EE12 | The experience of experiencing the VR exhibition gave me a break from my daily life and rest. | ||

| EE13 | I want to spend more time on VR exhibitions. | ||

| EE14 | Experiencing the VR exhibition immersed me in another art space for a moment. | ||

| EE15 | My experience in virtual space gave me a chance to see myself in a new way. | ||

| Aesthetic experience | AE1 | I am very satisfied with the design style of the VR exhibition experience showroom. | [60,62] |

| AE2 | My visit to the VR exhibition gave me a wonderful and sensual experience. | ||

| AE3 | The lighting in the VR exhibition experience exhibition hall is just right. | ||

| AE4 | The sound effects during the VR exhibition experience are just right. | ||

| AE5 | The video and music of the VR exhibition are well connected. | ||

| AE6 | Experience the VR exhibition, the real and the image perfect fusion. | ||

| AE7 | The environment of the exhibition space is very charming. | ||

| AE8 | The exhibition space is designed with an aesthetic sense. | ||

| AE9 | The atmosphere of the experience space is harmonious. | ||

| Presence | PS1 | I felt that the exhibits in these virtual spaces were like real exhibits in front of my eyes. | [2] |

| PS2 | I feel like I’m looking at artworks in the exhibition hall. | ||

| PS3 | I feel that I also participated in the exhibition. | ||

| PS4 | I feel that the VR exhibition screen exists in real life. | ||

| PS5 | VR exhibition works can bring a multi-sensory immersive experience. | ||

| PS6 | I feel that the exhibits are like being exhibited in front of my eyes. | ||

| PS7 | It feels like moving in the background of a VR exhibition. | ||

| Emotional responses | ER1 | I felt pleasure and satisfaction when I had an art experience in the environment of a VR exhibition. | [63] |

| ER2 | Visit the VR exhibition and feel very leisurely. | ||

| ER3 | I love watching VR exhibitions. | ||

| ER4 | Visiting the VR exhibition was both interesting and enjoyable. | ||

| Continued usage intention | CUI1 | I am currently using the VR exhibit and will continue to use it. | [64] |

| CUI2 | I hope to use VR exhibitions to visit often in the future. | ||

| CUI3 | I would recommend the VR exhibition to those around me. | ||

| CUI4 | I will always share wonderful VR exhibitions so that people around me can also see them. |

References

- Kim, B.; Yong, H. The types of online museum exhibitions on the post COVID-19 era. J. Korea Cult. Ind. 2020, 20, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L.; Lee, J.Y.; Liu, S.S. The Impact of the User Characteristics of the VR Exhibition on Space Participation and Immer sion. Int. J. Contents 2022, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J. The effect of 3D stereoscopic images: Realism, identification, and enjoyment of the movie Avatar. J. Korean J. 2010, 54, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C. Discussion on the Application of Virtual Reality Technology in Museums: Also talk about the creation process of virtual exhibition in Zhejiang Provincial Museum. China Inf. Ind. 2010, 7, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tinio, P.P.L.; Smith, J.K. (Eds.) The Cambridge Handbook of the Psychology of Aesthetics and the Arts; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; p. 620. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, B.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Koreanische, Z. Study on the Attributes of Building Online Exhibition Platforms: From the Organizer’s Point of View. Korean J. Econ. 2022, 40, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidianakis, E.; Partarakis, N.; Ntoa, S.; Dimopoulos, A.; Kopidaki, S.; Ntagianta, A.; Ntafotis, E.; Xhako, A.; Pervolarakis, Z.; Kontaki, E.; et al. The invisible museum: A user-centric platform for creating virtual 3D exhibitions with VR support. Electronics 2021, 10, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, N.; Gong, Q.; Zhou, J.P.; Chen, P.R.; Kong, W.Q.; Chai, C.L. Value-based model of user interaction design for virtual museum. CCF Trans. Pervasive Comput. Interact. 2021, 3, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.S.; Nam, Y.J. A study on the Influence of VR experience and the perception of service quality on the museum visitors satisfaction and revisit intention. Int. J. Tour. Manag. 2022, 37, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, A.; Cheung, C.M.K. Beyond hedonic enjoyment: Conceptualizing eudaimonic motivation for personal informatics technology usage. In Design, User Experience, and Usability: Designing Pleasurable Experiences, Proceedings of the 6th International Conference, DUXU 2017, Held as Part of HCI International 2017, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–14 July 2017; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmetkamp, S. Gaining Perspectives on Our Lives: Moods and Aesthetic Experience. Philosophia 2017, 45, 1681–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.G.; Fiore, A.M.; Zhang, L. Impact of website design features on experiential value and patronage intention toward online mass customization sites. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 25, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.H.; Yoon, E.J. The effect of exhibition experience factors on visitors’ quality of experience, satisfaction and behavioral intention. Int. J. Trad. Fairs. Exhib. Stud. 2019, 14, 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the experience economy. HBR 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, E.Y. The effects of augmented reality mobile app advertising: Viral marketing via shared social experience. JBR 2021, 122, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y. New orientation of study on economic psychology and behaviour. Transl. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montag, C.; Lachmann, B.; Herrlich, M.; Zweig, K. Addictive Features of Social Media/Messenger Platforms and Freemium Games against the Background of Psychological and Economic Theories. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Dieck, M.; Lee, H.; Chung, N. Effects of virtual reality and augmented reality on visitor experiences in museum. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Springer: Cham, The Netherland, 2016; pp. 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Wang, X.J. Automobile exhibition design in experience economy: Taking the beijing auto museum as an example. Art. Design. 2018, 305, 128–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bychkov, V.V.; Mankovskaya, N.B. Artistisity as metaphysical foundation of aesthetic experience and criterion of art authenticity identification. Vestn. Slavianskikh Kult. Bull. Slav. Cult. Sci. Inf. J. 2017, 43, 220–241. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, E.; Saker, M. Art museums and the incorporation of virtual reality: Examining the impact of VR on spatial and social norms. Convergence 2020, 26, 1159–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.S.; Lee, M.J. A study on the usability evaluation of online exhibitions incorporating VR technology: Focusing on ux design elements according to user experience. J. Korean Soc. Des. Cult 2022, 28, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.D. The tourist in the experience economy. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2007, 7, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, G.; Najmin, S.; Thirumoorthi, T.; Taha, A.Z. Examining visitors’ experience with Batu Cave, using the four realm experiential theory. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2017, 3, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Huang, L.X. Study on the path of public library webcast enhancement from the perspective of experience economy. Libr. Work. Study 2022, 312, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena, D.; Vlasios, K. Virtual Reality: A journey from vision to commodity. IEEE Ann. Hist. Comput. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Witham, M. Dimensions of cruisers’ experiences, satisfaction and intention to recommend. J. Travel. Res. 2009, 49, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzynski, S.E.; Jones, M.; Steele, J. A physically active experience: Setting the stage for a new approach to engage children in physical activity using themed entertainment experiences. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 2579–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluri, A. Mobile augmented reality (MAR) game as a travel guide: Insights from Pokemon GO. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2017, 8, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.; Mishra, S. Application of confirmatory factor analysis and structural modelling to measure experience economy of tourists. Nmims. Manag. Rev. 2022, 30, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Oh, S. The users’ intention to participate in a VR/AR sports experience by applying the extended technology acceptance model (ETAM). Healthcare 2022, 10, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.W.; Chung, J.E.; Ann, M.F. The effects of shopping motivation and an experiential marketing approach on consumer responses toward small apparel retailers. Fash. Ind. Educ. 2017, 15, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J. The transition of art exhibition in the age of immersive media. ICELA 2022, 5, 2352–5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annechini, C.; Menardo, E.; Hall, R.; Pasini, M. Aesthetic Attributes of Museum Environmental Experience: A Pilot Study with Children as Visitors. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 508300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genc, V.; Gulertekin, G.S. The effect of perceived authenticity in cultural heritage sites on tourist satisfaction: The moderating role of aesthetic experience. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannis, X.; Argyris, A. Ontological and conceptual challenges in the study of aesthetic experience. Philos. Psychol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diodato, R. Virtual reality and aesthetic experience. Philosophies. 2022, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, C.Q.; Robert, B. Self-discovery and redesign of immersive art aesthetic experience. Ind. Eng. Des. 2020, 2, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoos, M.; Glaser, M.; Schwan, S. Aesthetic experience of representational art: Liking Is affected by audio-information naming and explaining inaccuracies of historical paintings. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 613391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paolis, L.T.; De Luca, V. The effects of touchless interaction on usability and sense of presence in a virtual environment. Virtual Reality 2022, 26, 1551–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, R.Y.; Catheryn, K.L.; Leigh, E.P. VR the world: Experimenting with emotion and presence for tourism marketing. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, R.Y.; Catheryn, K.L.; Leigh, E.P. Virtual reality and tourism marketing: Conceptualizing a framework on presence, emotion, and intention. Curr. Issues. Tour. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federica, P.; Alessandro, P.; Ambra, F.; Giacomo, G.; Andrea, Z.; Fabrizia, M. What Is the relationship among positive emotions, sense of presence, and ease of interaction in virtual reality systems? An on-site evaluation of a commercial virtual experience. Presence 2018, 27, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, J.P.; Lee, H.W.; Han, J.W. Creating sense of presence in a virtual reality experience: Impact on neurophysiological arousal and attitude towards a winter sport. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 23, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.S.; Yu, H.S.; Shin, D.H. User experience in virtual reality games: The effect of presence on enjoyment. Inf. Commun. Policy Soc. 2017, 24, 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.Q. An analysis of the application of VR technology in thematic exhibitions in the new media era. Technol. Chin. Mass Media 2020, 12, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.L. Online virtual art exhibition helps scene proximity experience research. Beauty. Times 2021, 1, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.J.; Kwon, O.B. GImpact of presence, spatial ability, and esthetics on the continuance intention of use of augmented reality and virtual reality. Bus. Educ. Res. 2018, 33, 355–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.-L. Factors that influence virtual tourism holistic image: The moderating role of sense of presence. Sustainability 2022, 14, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, L.; Menon, K. Multiple roles of consumption emotions in post-purchase satisfaction with extended service transations. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2000, 11, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thüring, M.; Mahlke, S. Usability, aesthetics and emotions in human: Technology interaction. Int. J. Psychol. 2007, 42, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.K.; Lee, S.W.; Chung, B.D.; Park, C.S. Users’ emotional valence, arousal, and engagement based on perceived usability and aesthetics for web sites. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2014, 31, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creusen, M.E.H. Research opportunities related to consumer response to product design. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2011, 28, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.W.; Fiore, A.M.; Niehm, L.S.; Lorenz, F.O. The role of experiential value in online shopping: The impacts of product presentation on consumer responses towards an apparel website. Internet. Res. 2009, 19, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.R. The influence of Pilates participants’ empirical values on their emotional responses and behavioral intentions. JER 2019, 15, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, A.M.; Kim, J. An integrative framework capturing experiential and utilitarian shopping experience. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. 2007, 35, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.X.; Li, F.X. Travelers’ emotional experiences during the COVID-19 outbreak: The development of a conceptual model. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.K.; Yun, J.Y. User experience and preference study according to types of online exhibition platforms. Bull. Korean Soc. Basic Des. Art. 2021, 22, 481–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Park, Y.A. A study on the structural relationship between augmented reality experience, presence and visit intention: Focused on the moderating effect of visit experience. J. Mark. Stud. 2019, 27, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H. A Study of the Structural Relationships among Experience Value, Value Co-Creation Attitude, and Behavior Based on Museum Immersive Contents. Ph.D. Thesis, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.J.; Lee, C.K.; Park, J.A.; Hwang, Y.H.; Reisinger, Y. The Influence of Tourist Experience on Perceived Value and Satisfaction with Temple Stays: The Experience Economy Theory. J Travel. Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Chang, Y. The effect of teachers’ savoring on creative behaviors: Mediating effects of creative self-efficacy and aes thetic experience. Int. J. Educ. Methodol. 2019, 5, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Cho, K.M. The structural relationship among virtual reality sports users’ presence, emotional response, sports atti tude and behavioral intention. Korea. J. Sport. Manag. 2019, 24, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetu, S.N.; Islam, M.M.; Promi, S.I. An empirical investigation of the continued usage intention of digital wallets: The moderating role of perceived technological innovativeness. Future Bus. J. 2022, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.; Hayes, A. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H. The relationship among experience factors of social trytoursumer, emotional responses, citizenship behavior, and long-term relationship orientation. Tour. Leis. Res. 2016, 28, 253–272. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y.; Park, Y.A. A effects of augmented reality experience factors on emotional responses and intention to visit: A focus on the moderating, role of presence. Res. Netw. Electron. Commer 2019, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency | The Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 258 | 47.51 |

| Female | 285 | 52.49 | |

| Age | 18 years old and below | 119 | 21.92 |

| 18–26 years old | 293 | 53.96 | |

| 27–33 years old | 92 | 16.94 | |

| 34–40 years old | 26 | 4.79 | |

| 40 years old and above | 13 | 2.39 | |

| Education | Highschool graduation | 28 | 5.16 |

| Junior college degree | 173 | 31.86 | |

| Bachelor degree | 201 | 37.01 | |

| Master degree or above | 141 | 25.97 | |

| Frequency of use | Every day | 31 | 5.71 |

| Once every 1 to 3 days | 88 | 16.20 | |

| Every 4 to 7 days | 281 | 51.75 | |

| More than 7 days | 143 | 26.34 |

| Variables | M | SD | Cronbach’s α | EE | AE | PS | CUI | ER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE | 3.2252 | 0.68560 | 0.873 | 1 | ||||

| AE | 3.2533 | 0.81493 | 0.870 | 0.489 ** | 1 | |||

| PS | 3.2584 | 0.74852 | 0.880 | 0.633 ** | 0.548 ** | 1 | ||

| CUI | 3.2808 | 0.91980 | 0.921 | 0.480 ** | 0.392 ** | 0.593 * | 1 | |

| ER | 3.2205 | 1.02968 | 0.906 | 0.481 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.543 ** | 0.406 ** | 1 |

| Relationship | β | SE | 95% CI | p | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Direct effect | ||||||

| EE→CUI | 0.481 | 0.051 | 0.546 | 0.745 | 0.000 | Supported |

| AE→CUI | 0.374 | 0.045 | 0.334 | 0.511 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Indirect effect | ||||||

| EE→PS→CUI | 0.335 | 0.054 | 0.235 | 0.442 | 0.000 | Supported |

| AE→PS→CUI | 0.287 | 0.043 | 0.206 | 0.371 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Relationship | β | SE | 95% CI | t | p | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| EE × ER→CUI | –0.024 | 0.045 | –0.112 | 0.065 | –0.525 | 0.600 | Not supported |

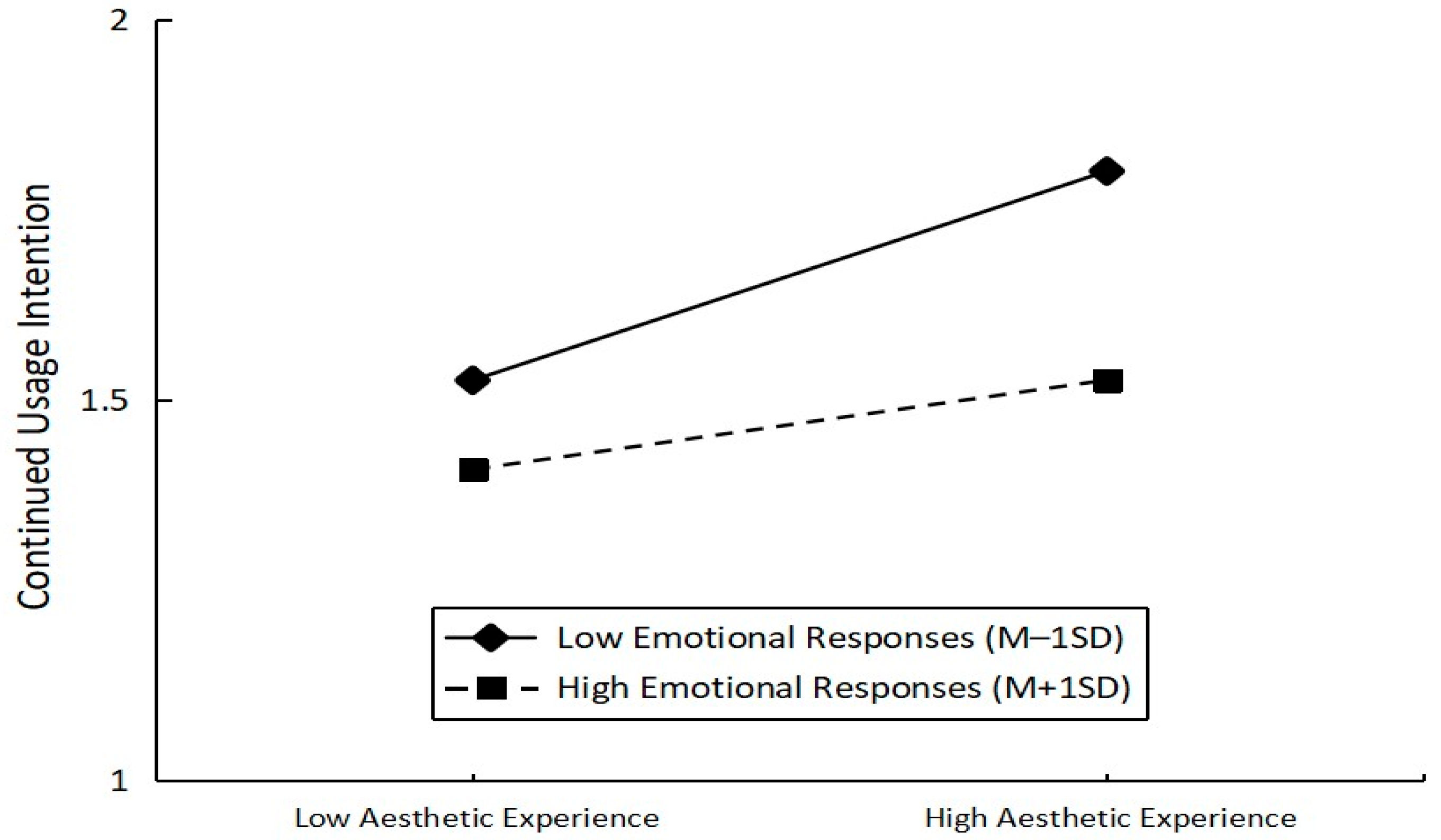

| AE × ER→CUI | 0.079 | 0.037 | 0.007 | 0.150 | 2.158 | 0.031 * | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Lee, J.-Y.; Liu, S.; Hu, L. The Role of Emotional Responses in the VR Exhibition Continued Usage Intention: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065001

Wang M, Lee J-Y, Liu S, Hu L. The Role of Emotional Responses in the VR Exhibition Continued Usage Intention: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(6):5001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065001

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Minglu, Jong-Yoon Lee, Shanshan Liu, and Lingling Hu. 2023. "The Role of Emotional Responses in the VR Exhibition Continued Usage Intention: A Moderated Mediation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 6: 5001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065001

APA StyleWang, M., Lee, J.-Y., Liu, S., & Hu, L. (2023). The Role of Emotional Responses in the VR Exhibition Continued Usage Intention: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 5001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065001