Lessons Learned—The Impact of the Third Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic on German Waldorf Parents’ Support Needs and Their Rating of Children’s Health-Related Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Study Instruments

2.3. Outcome Parameters

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

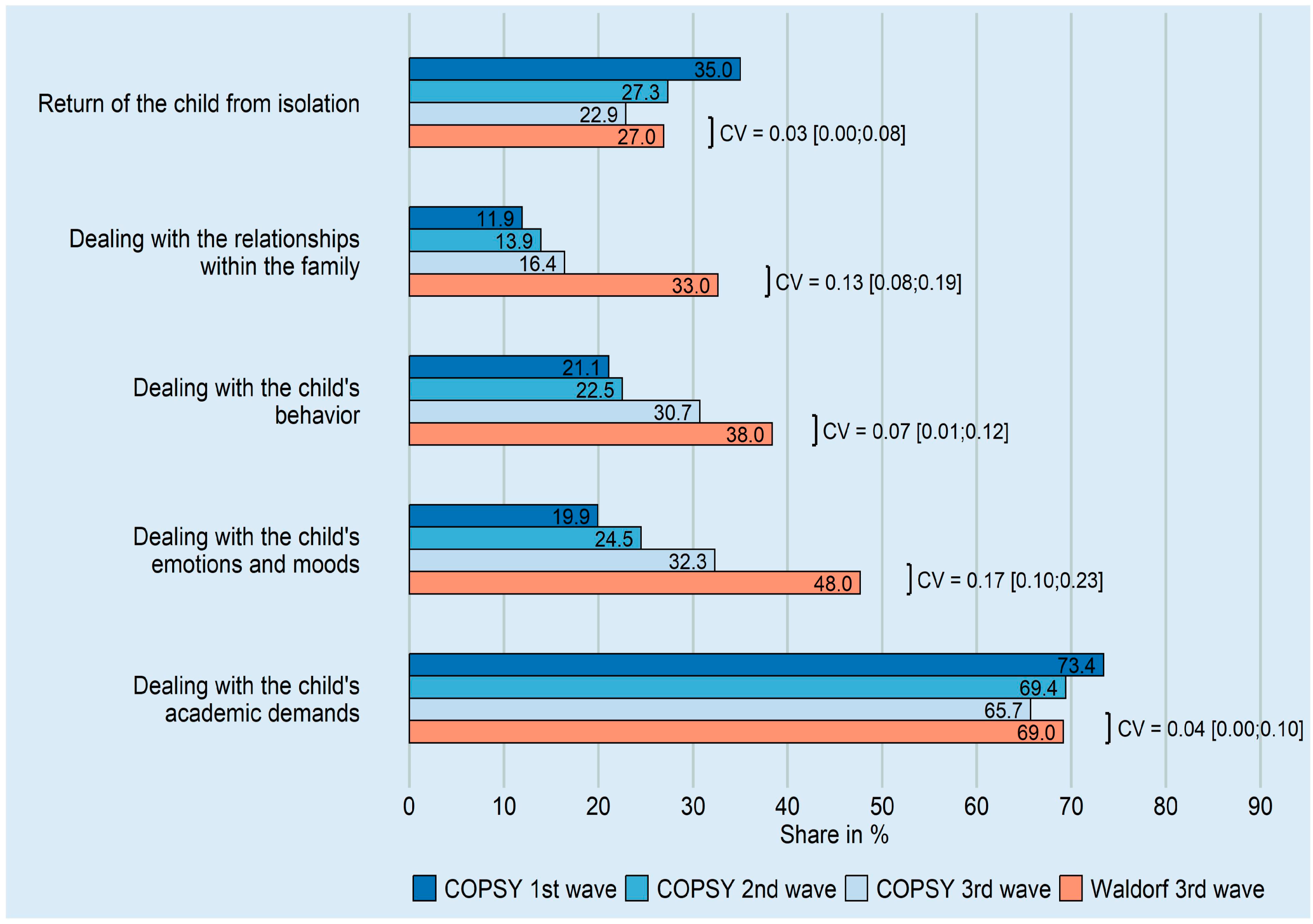

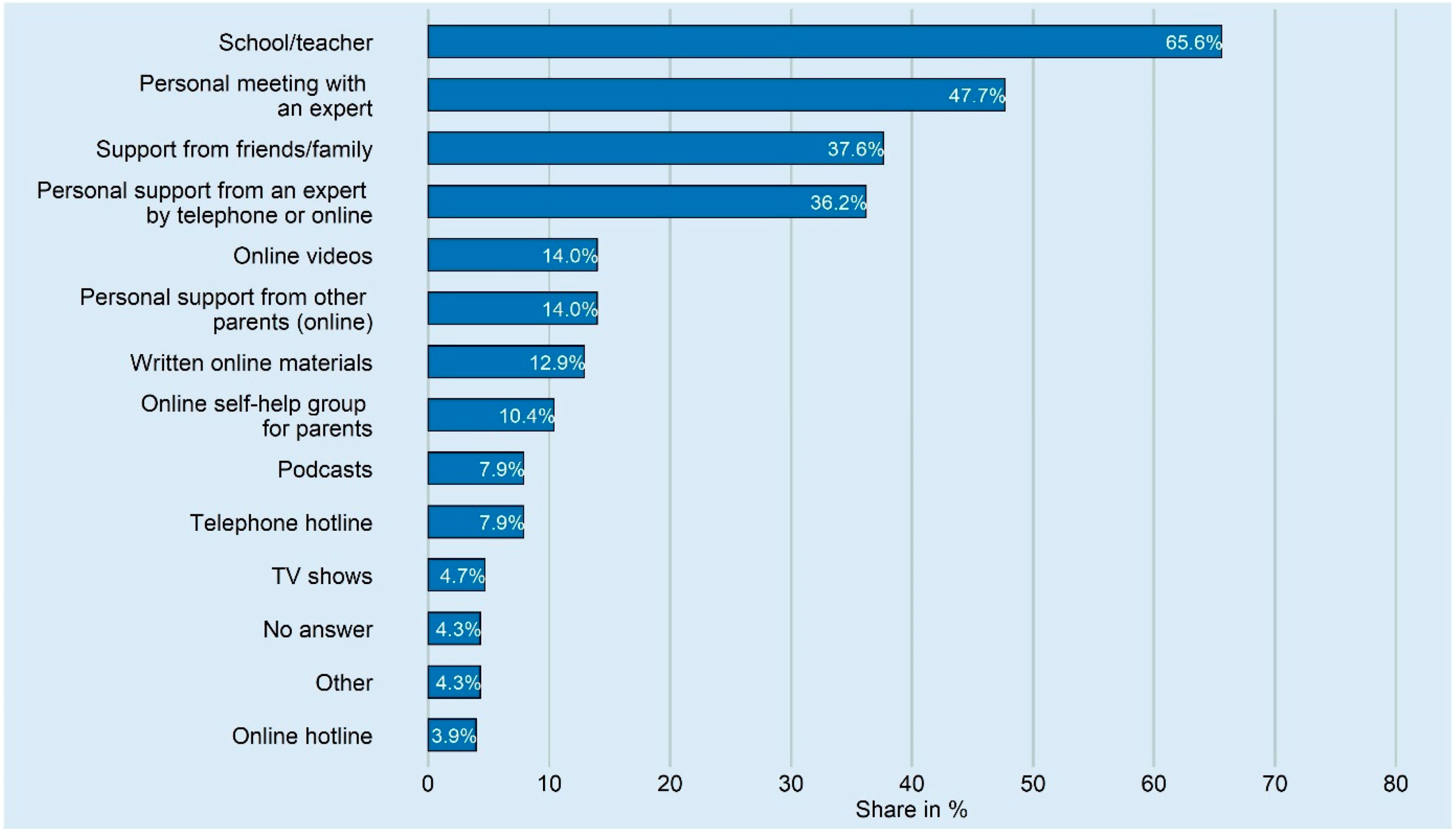

3.2. Support Needs of Parents

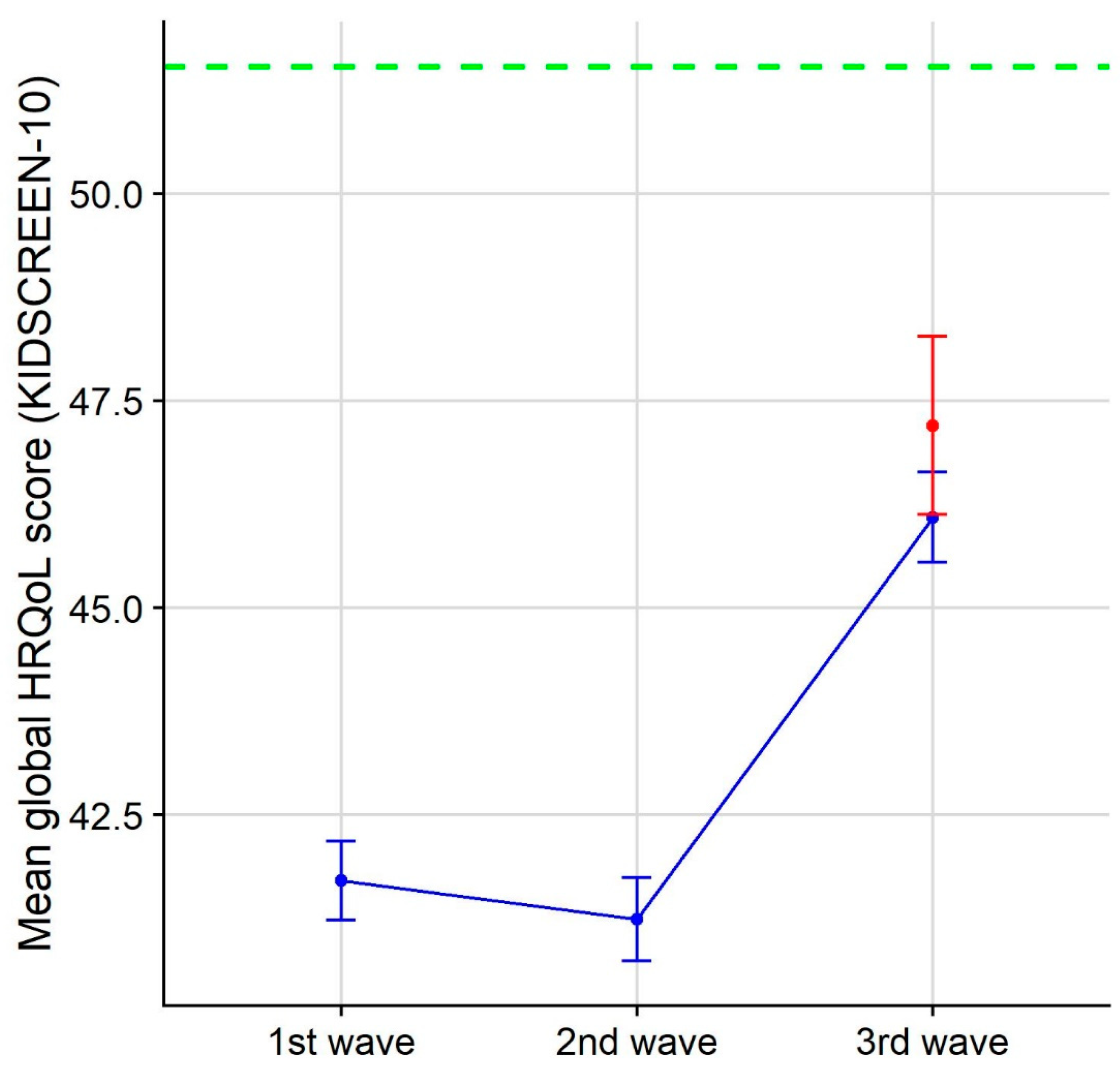

3.3. HRQoL of Children

3.4. Teaching during the Third Wave

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, S.; Lombardi, J.; Fisher, P.A. The COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Households of Young Children With Special Healthcare Needs. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2022, 47, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, P.; Bharti, B.; Sidhu, M. Stress and parenting during the COVID-19 pandemic: Psychosocial impact on children. Indian J. Pediatrics 2021, 88, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGoron, L.; Wargo Aikins, J.; Trentacosta, C.J.; Gómez, J.M.; Beeghly, M. School support, chaos, routines, and parents’ mental health during COVID-19 remote schooling. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 37, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Erhart, M.; Devine, J.; Gilbert, M.; Reiss, F.; Barkmann, C.; Siegel, N.A.; Simon, A.M.; Hurrelmann, K.; Schlack, R.; et al. Child and Adolescent Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results of the Three-Wave Longitudinal COPSY Study. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 71, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldus, C.; Franz, S.; Thomasius, R. Help Needs among Parents and Families in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vescovi, G.; Riter, H.S.; Azevedo, E.C.; Pedrotti, B.G.; Frizzo, G.B. Parenting, mental health, and COVID-19: A rapid systematic review. Psicol. Teor. Prática São Paulo 2021, 23, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, A.K. Parental burnout and child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Fam. Violence 2020, 37, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, S.W.; Henkhaus, L.E.; Zickafoose, J.S.; Lovell, K.; Halvorson, A.; Loch, S.; Letterie, M.; Davis, M.M. Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e2020016824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Ward, K.P.; Chang, O.D.; Downing, K.M. Parenting activities and the transition to home-based education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 122, 105585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brom, C.; Lukavský, J.; Greger, D.; Hannemann, T.; Straková, J.; Švaříček, R. Mandatory home education during the COVID-19 lockdown in the Czech Republic: A rapid survey of 1st–9th graders’ parents. In Frontiers in Education; Frontiers: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, M.H. “Parental burnout”: The state of the science. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2020, 2020, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.Y.H.; Li, J.-B. Hong Kong Children’s School Readiness in Times of COVID-19: The Contributions of Parent Perceived Social Support, Parent Competency, and Time Spent with Children. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluver, L.; Lachman, J.M.; Sherr, L.; Wessels, I.; Krug, E.; Rakotomalala, S.; Blight, S.; Hillis, S.; Bachman, G.; Green, O.; et al. Parenting in a time of COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 10231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, R.C. Dyadic associations between COVID-19-related stress and mental well-being among parents and children in Hong Kong: An actor–partner interdependence model approach. Fam. Process 2022, 61, 1730–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, B.; Fu, M.; Huang, N.; Hu, Q.; Guo, J. Associations of youth mental health, parental psychological distress, and family relationships during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prime, H.; Wade, M.; Browne, D.T. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calear, A.L.; McCallum, S.; Morse, A.R.; Banfield, M.; Gulliver, A.; Cherbuin, N.; Farrer, L.M.; Murray, K.; Rodney Harris, R.M.; Batterham, P.J. Psychosocial impacts of home-schooling on parents and caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubb, S.; Jones, M.-A. Learning from the COVID-19 home-schooling experience: Listening to pupils, parents/carers and teachers. Improv. Sch. 2020, 23, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorell, L.B.; Skoglund, C.; de la Peña, A.G.; Baeyens, D.; Fuermaier, A.; Groom, M.J.; Mammarella, I.C.; Van der Oord, S.; van den Hoofdakker, B.J.; Luman, M.; et al. Parental experiences of homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic: Differences between seven European countries and between children with and without mental health conditions. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Kaman, A.; Otto, C.; Adedeji, A.; Napp, A.K.; Becker, M.; Blanck-Stellmacher, U.; Löffler, C.; Schlack, R.; Hölling, H.; et al. Seelische Gesundheit und psychische Belastungen von Kindern und Jugendlichen in der ersten Welle der COVID-19-Pandemie–Ergebnisse der COPSY-Studie. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2021, 64, 1512–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Kaman, A.; Erhart, M.; Otto, C.; Devine, J.; Löffler, C.; Hurrelmann, K.; Bullinger, M.; Barkmann, C.; Siegel, N.A.; et al. Quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a two-wave nationwide population-based study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidley, J.M. Prospective youth visions through imaginative education. Futures 1998, 30, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paull, J.; Hennig, B. Rudolf Steiner Education and Waldorf Schools: Centenary World Maps of the Global Diffusion of “The School of the Future”. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 6, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, M. Education for Freedom: The Goal of Steiner/Waldorf Schools. Alternative Education for the 21st Century; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 209–255. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza, D.L. Learning and human development in Waldorf pedagogy and curriculum. Encount. Educ. Mean. Soc. Justice 2012, 25, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rawson, M. Steiner Waldorf Pedagogy in Schools: A Critical Introduction; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mavrelos, M.; Daradoumis, T. Exploring Multiple Intelligence Theory Prospects as a Vehicle for Discovering the Relationship of Neuroeducation with Imaginative/Waldorf Pedagogy: A Systematic Literature Review. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Herdman, M.; Devine, J.; Otto, C.; Bullinger, M.; Rose, M.; Klasen, F. The European KIDSCREEN approach to measure quality of life and well-being in children: Development, current application, and future advances. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Erhart, M.; Rajmil, L.; Herdman, M.; Auquier, P.; Bruil, J.; Power, M.; Duer, W.; Abel, T.; Czemy, L.; et al. Reliability, construct and criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score: A short measure for children and adolescents’ well-being and health-related quality of life. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 1487–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U. Kidscreen Group Europe. The Kidscreen Questionnaires: Quality of Life Questionnaires for Children and Adolescents; Handbook; Pabst Science Publishers: Lengerich, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Mangiafico, S. Rcompanion: Functions to Support Extension Education Program Evaluation. R package version 2.4.21. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rcompanion (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Ellis, P.D. The Essential Guide to Effect Sizes: Statistical Power, Meta-Analysis, and the Interpretation of Research Results; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Team RDC. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; Team RDC: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; RStudio: Boston, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbing, P.R. PAutilities: Streamline Physical Activity Research. 2022. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=PAutilities (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Lau, E.Y.H.; Lee, K. Parents’ views on young children’s distance learning and screen time during COVID-19 class suspension in Hong Kong. Early Educ. Dev. 2021, 32, 863–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathgeb, C.; Schillok, H.; Voss, S.; Coenen, M.; Schulte-Körne, G.; Merkel, C.; Eitze, S.; Jung-Sievers, C.; COSMO Study Team. Emotional Situation of Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany: Results from the COVID-19 Snapshot Monitoring Study (COSMO). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, J.E.; Schillok, H.; Merkel, C.; Voss, S.; Coenen, M.; De Bock, F.; von Rüden, U.; Bramesfeld, A.; Jung-Sievers, C. Belastung von Eltern mit Kindern im Schulalter während verschiedener Phasen der COVID-19-Pandemie in Deutschland: Eine Analyse der COVID-19-Snapshot-Monitoring-(COSMO-) Daten. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2021, 64, 1500–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassinat, J.R.; Whiteman, S.D.; Serang, S.; Dotterer, A.M.; Mustillo, S.A.; Maggs, J.L.; Kelly, B.C. Changes in family chaos and family relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 57, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, G.; Lanier, P.; Wong, P.Y.J. Mediating effects of parental stress on harsh parenting and parent-child relationship during coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Singapore. J. Fam. Violence 2020, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orgilés, M.; Morales, A.; Delvecchio, E.; Mazzeschi, C.; Espada, J.P. Immediate psychological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nöthig, W.; Klee, L.; Fabrice, A.; Eisenburger, N.; Feddern, S.; Kossow, A.; Niessen, J.; Schmidt, N.; Wiesmüller, G.A.; Grüne, B.; et al. Stay at Home Order—Psychological Stress in Children, Adolescents, and Parents during COVID-19 Quarantine—Data of the CoCo-Fakt Cohort Study, Cologne. Adolescents 2022, 2, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koolmann, S.; Petersen, L.; Ehrler, P. Waldorf-Eltern in Deutschland: Status, Motive, Einstellungen, Zukunftsideen; Beltz Juventa: Baden-Württemberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| COPSY Sample | Waldorf Sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Wave (n = 1586) [20] | 2nd Wave (n = 1923) [21] | 3rd Wave (n = 2097) [4] | 3rd Wave (n = 431 Parents, n = 511 Children) | 3rd Wave: Waldorf vs. COPSY Sample | ||

| Children | n (%)/M ± SD | Cohen’s d/Cramér’s V | ||||

| Age, in years a | - | 12.25 ± 3.30 | 12.67 ± 3.29 | 13.21 ± 3.30 | 11.66 ± 2.97 | 0.49 |

| Gender | Male | 791 (49.9) | 964 (50.1) | 1030 (49.1) | 240 (47.0) | 0.11 |

| Female | 793 (50.0) | 956 (49.7) | 1055 (50.3) | 257 (50.3) | ||

| Diverse | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 10 (0.5) | 7 (1.4) | ||

| No answer | 1 (0.1) | - | - | 7 (1.4) | ||

| BMI percentile b | - | - | - | - | 44.68 ± 30.01 | - |

| Migration background | No | 1332 (84.0) | 1608 (83.6) | 1741 (83.0) | 474 (92.8) | 0.19 |

| Yes | 254 (16.0) | 315 (16.4) | 356 (17.0) | 26 (5.1) | ||

| No answer | - | - | - | 11 (2.2) | ||

| Parents | ||||||

| Age c | - | 43.99 ± 7.36 | 44.05 ± 7.35 | 44.41 ± 7.44 | 46.25 ± 6.68 | 0.26 |

| Number of children d | - | - | - | - | 1.65 ± 0.78 | - |

| Marital status | Single | 140 (8.8) | - | - | 24 (5.6) | - |

| Married | 1097 (69.2) | - | - | 326 (75.6) | ||

| In a registered partnership | 13 (0.8) | - | - | 2 (0.5) | ||

| In a committed relationship | 216 (13.6) | - | - | 27 (6.3) | ||

| Divorced | 108 (6.8) | - | - | 40 (9.3) | ||

| Widowed | 12 (0.8) | - | - | 6 (1.4) | ||

| No answer | - | - | - | 6 (1.4) | ||

| Education e | Higher education entrance qualification/Abitur | - | - | - | 596 (69.1) | - |

| Advanced technical college certificate | - | - | - | 125 (14.5) | ||

| General certificate of secondary education | - | - | - | 92 (10.9) | ||

| Certificate of secondary education | - | - | - | 34 (3.9) | ||

| No school leaving certificate | - | - | - | 4 (0.5) | ||

| No answer | - | - | - | 9 (1.0) | ||

| Occupation e | Full-time employed | 820 (51.7) | 990 (51.5) | 1069 (51.0) | 313 (36.3) | 0.33 |

| Part-time employed | 453 (28.6) | 555 (28.9) | 616 (29.4) | 234 (27.1) | ||

| Self-employed | 67 (4.2) | 78 (4.1) | 81 (3.9) | 185 (21.5) | ||

| Other employment | 32 (2.0) | 34 (1.8) | 40 (1.9) | 30 (3.5) | ||

| Housewife, househusband | 109 (6.9) | 130 (6.8) | 142 (6.8) | 41 (4.8) | ||

| On parental leave | 29 (1.8) | 26 (1.4) | 31 (1.5) | 16 (1.9) | ||

| Unemployed | 42 (2.6) | 68 (3.5) | 66 (3.1) | 12 (1.4) | ||

| Retiree/pensioner | 34 (2.1) | 42 (2.2) | 52 (2.5) | 10 (1.2) | ||

| No answer | - | - | - | 21 (2.4) | ||

| COPSY Sample | Waldorf Sample | |||

| Answer Options | 1st Wave | 2nd Wave (n = 1625) | 3rd Wave (n = 1618) | 3rd Wave (n = 394) |

| Yes | 63.0% | 58.7% (n = 953) | 59.9% (n = 968) | 70.8% (n = 279) |

| …always | - | 3.6% (n = 58) | 3.2% (n = 52) | 9.9% (n = 39) |

| …rather often | - | 9.4% (n = 153) | 7.0% (n = 113) | 15.7% (n = 62) |

| …occasionally | - | 45.7% (n = 742) | 49.7% (n = 803) | 45.2% (n = 178) |

| Never | 37.0% | 41.3% (n = 671) | 40.1% (n = 650) | 29.2% (n = 115) |

| Split | Response Rate | Dealing with the Relationships within the Family | Dealing with the Child’s Emotions and Moods | Dealing with the Child’s Behavior | Return of the Child from Isolation | Dealing with the Child’s Academic Demands | Fisher. p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access to a garden or terrace | Yes | 223/350 (63.7%) | 71 (31.8%) | 110 (49.3%) | 84 (37.7%) | 60 (26.9%) | 152 (68.2%) | 0.954 |

| No | 34/48 (70.8%) | 12 (35.3%) | 16 (47.1%) | 16 (47.1%) | 9 (26.5%) | 23 (67.7%) | ||

| Number of persons in the household | ≥4 | 195/293 (66.6%) | 69 (35.4%) | 98 (50.3%) | 84 (43.1%) | 48 (24.6%) | 128 (65.6%) | 0.066 |

| <4 | 63/109 (57.8%) | 14 (22.2%) | 28 (44.4%) | 16 (25.4%) | 22 (34.9%) | 47 (74.6%) | ||

| Number of rooms in the house/apartment | ≥5 | 155/243 (63.8%) | 51 (32.9%) | 74 (47.8%) | 57 (36.8%) | 42 (27.1%) | 102 (65.8%) | 0.987 |

| <5 | 101/154 (65.6%) | 32 (31.7%) | 50 (49.5%) | 42 (41.6%) | 27 (26.7%) | 71 (70.3%) | ||

| Number of children aged between 7 and 17 years | >1 child | 121/181 (66.9%) | 36 (29.8%) | 57 (47.1%) | 48 (39.7%) | 31 (25.6%) | 84 (69.4%) | 0.944 |

| 1 child | 137/220 (62.3%) | 47 (34.3%) | 69 (50.4%) | 52 (37.96%) | 39 (28.5%) | 91 (66.4%) |

| COPSY Sample | Waldorf Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 3 | |

| n | 1586 | 1625 | 1618 | 413 |

| M ± SD | 41.70 ± 9.69 | 41.24 ± 10.33 | 46.09 ± 11.19 | 47.33 ± 11.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vagedes, J.; Michael, K.; Sobh, M.; Islam, M.O.A.; Kuderer, S.; Jeske, C.; Kaman, A.; Martin, D.; Vagedes, K.; Erhart, M.; et al. Lessons Learned—The Impact of the Third Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic on German Waldorf Parents’ Support Needs and Their Rating of Children’s Health-Related Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064756

Vagedes J, Michael K, Sobh M, Islam MOA, Kuderer S, Jeske C, Kaman A, Martin D, Vagedes K, Erhart M, et al. Lessons Learned—The Impact of the Third Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic on German Waldorf Parents’ Support Needs and Their Rating of Children’s Health-Related Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(6):4756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064756

Chicago/Turabian StyleVagedes, Jan, Karin Michael, Mohsen Sobh, Mohammad O. A. Islam, Silja Kuderer, Christian Jeske, Anne Kaman, David Martin, Katrin Vagedes, Michael Erhart, and et al. 2023. "Lessons Learned—The Impact of the Third Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic on German Waldorf Parents’ Support Needs and Their Rating of Children’s Health-Related Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 6: 4756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064756

APA StyleVagedes, J., Michael, K., Sobh, M., Islam, M. O. A., Kuderer, S., Jeske, C., Kaman, A., Martin, D., Vagedes, K., Erhart, M., Ravens-Sieberer, U., & Zdražil, T. (2023). Lessons Learned—The Impact of the Third Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic on German Waldorf Parents’ Support Needs and Their Rating of Children’s Health-Related Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 4756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064756