Don’t Follow the Smoke—Listening to the Tobacco Experiences and Attitudes of Urban Aboriginal Adolescents in the Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health (SEARCH)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualitative Approach

2.2. Researcher Characteristics

2.3. Setting

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Sample & Recruitment

2.6. Data Collection Methods

2.6.1. Instruments

2.6.2. Data Processing

2.6.3. Data Analysis

2.6.4. Member Checking/Validation of Themes

3. Results

3.1. Results Overview

3.1.1. General Concepts of Health and Wellbeing

3.1.2. Personal Exposure and Experiences of Smoking/Non-Smoking

I think I only smoke due to my peace, that’s like my peace. You know. My little getaway from my little one and partner and yeah. And I think I smoke…I really do, I just can’t find myself to quit right now. When I become more stable, when I get my own house that I know I’m not going to get kicked out of. And when I get the kids settled, and like I can start focusing on my health again. I really want to quit, I just can’t right now. I think once I get more stable, and it’d be easier for me to quit.[11.F1]

3.2. Key Smoking/Non-Smoking Themes

3.2.1. Theme 1. Drawing Strength from Culture and Community

Community, Cultural Connections and Role Models

I reckon, just like if you’re someone that’s deeply connected with your culture, it gives you like um, I don’t know, just like a sense of belonging, and it just makes you not want to smoke because you’re more interested in, in your culture. But, like, so could be either studying, it could be working with the community. It could be um, studying your culture. Like yeah, and just, I feel that being connected to your culture, it does um make you want to smoke less, just because of wanting to fit in with the, the rest of your community and stuff like that.[11.F2]

Role models. Just don’t be a follower, be a leader. And then strong community, ah, connection to my community. So, keep everyone in the community strong, try and quit smoking. Be healthy. Yeah, live longer.[4.M1]

3.2.2. Theme 2. How the Smoking Environment Shapes Attitudes and Intentions

Role Models

Like role model, like it’s in there, but I feel like it can kind of be wrong, cos if your role model smokes, you’re going to kind of want to be like him.[7.F1]

Friends Who Smoke and Smoking at School

Yeah, it’s going through your mind “what are they going to think of me if I say no”.[2.F2]

Yeah, I’ve tried cigarettes but I don’t smoke, occasionally. Like when I’m around parties and all that, it’s kind of a social thing where you feel pressured to smoke, in front of everyone. And so obviously, I just usually do it at parties I think.[10.F1]

[RO] Do you think that your main reason for starting was just because of your friends? Yep?

And now I’ve got no friends I’ve only got me and my two kids[2.F1]

[RO] Kids. Yep.

It’s nothing to be proud about now.[2.F1]

But, when I became an adult and started working and stuff, and started hanging round people that did smoke, I did end up picking it up. So I shouldn’t even have started. I’ve only been smoking for about four or five years, but since I have been smoking, I’ve gotten pretty bad at it.[11.F2]

[I1] Um, how’d you feel after your first cigarette?

I started choking a lot. Like, I couldn’t really handle it, that was then, and then I started a lot. But, um, yeah. I started smoking probably only socially. So I’d go and just have a yarn with the girls, I’d have a smoke. And then soon it started me going out by myself to smoke. And then I just started going again and again, and I just never stopped.[11.F2]

Everyone just thinks like they’re wannabees. But, then they think to themselves “oh, we’re top shit” and all that…They think that they’re like seventeen, but they’re like twelve, fifteen[7.F1]

The teacher smokes, so…[8.F2]

It can really put an influence on the kids[8.F1]

But, the teachers go outside the school gate and, or some of them, or some of them wait until after school.[8.M1]

Smoking among Family Members

My mum’s a big smoker too. She started smoking when she was about twelve. Same with my brother. His father, he started smoking when he was about twelve. And my sister, she started smoking at a young age too. But, because I had health problems, I didn’t start smoking till later in life.[11.F2]

Yeah, Mum’s always been a smoker, since a young age, and so was her mother, well now me and my brother and sisters smoke, and my brother’s kids smoke.[11.F2]

But, my son, he’s only two, and his nan like came down from [Town2] and she just, she was staying at my house and she kept going out the back smoking. And after she left, he’d get up and be like “mum I want a moke”. That’s what he said…That’s what he said. And I was like “what?”. And then he’s like “I want a moke”. But, see, cos he noticed her smoking. Cos like nobody else in the house smokes, but seeing her kept, keep going outside, and then he probably thought he’d be able to go outside if he smoked. Like that’s, it shocked me when he said that.[1.F1]

[I1] What were your thoughts though when you seen your mum and that smoking?

Oh, I thought well “like, why do you smoke? Don’t do that, I don’t want you to die” or something, you know what I mean? And then now I’m doing it. Only when I drink though but still, I don’t reckon I should do it, cos, it’s not a healthy thing.[4.M1]

[I1] How does that make you feel, like having a night out with cigarettes?

I feel normal. It’s gross. They are, they’re gross. Um, most of my family smokes, not any more. My Nan used to smoke, she got cancer from it. Um, I used to hide her smokes from her. She used to get really angry. It was really funny. You know, it was a good thing. I used to, cos she had cancer, she wasn’t supposed to smoke. So. Yeah.[10.F1]

[I1] So knowing that Nan had cancer, what made, what made you want to smoke?

Mostly just people around me. I don’t do it all the time, you know, just mostly when I’m around people.[10.F1]

Smoke-Free Homes and Second-Hand Smoke Exposure

Knowledge of Harms and Impacts from Smoking

I think that’s the main reason I don’t do it. Cos you know, you see ads and that on TV. Um, yes. My biggest turnoff. Lung cancer and that’s a big thing. Don’t want to do it. Cos you put your family through a lot and that.[5.M1]

Yeah, I see ads and that, like quit smoking, call smoke line, or help line or whatever it is. I don’t know what it is. I seen it on ads.[4.M1]

[AHW] Do you see much though?

No I hardly see stuff about smoking to be honest. Only thing I see is all the stuff from the packets of people like dying and yeah. That stuff. That’s the main thing I see on the smokes.[4.M1]

[I1] What do you think when you see those?

It’s horrible.[4.M1]

[I1] Makes you not want to smoke.

Yeah, it does. It does. I don’t want to end up like that. Know what I mean? I don’t want anyone to end up like that.[4.M1]

Historical Knowledge and Awareness of Policy or Legislation Change

You had more freedom back then. And the smokes were cheaper back then. They were cheaper and you were allowed to smoke in more places. You know, there weren’t that many rules, but now there’s so many rules around it, and they’re so expensive, and it’s just, it’s starting to feel like it’s not worth it anymore, but it’s really hard to quit.[11.F2]

So, the laws we have now and that, do you, like wish they were there when you were little?[9.F2]

[I1] Yeah, definitely. Yes I do, yeah… But, these are things that I sit back actually, and think on, if all these things that are part of your generation now, the laws, and restrictions, if that was in place when I was younger, then yeah. Cos, you know, when I look back on it now, um, majority of my Elders have all passed away from cancer, from cigarettes. So, very preventable diseases. Um, if the laws had changed many, many years ago, then a lot of my Elders would still be alive today. I know that for sure. And the fact that cigarettes and alcohol was an introduced thing to our people you know, makes it even, um, makes it more upsetting in a way. There was no need for our people to have these influences given to us.

Vaping

Vaping’s stupid. What’s the point of that? [Mimes cloud of smoke][6.F1]

[I2] Maybe they think they look like a magician or something.

Yeah, like, they reckon they’re mad. They make themselves shame. So shame. Dumbest thing ever created…I see someone what an idiot, how stupid is that. How stupid is it to just stand there, inhale some smoke and blow it out? “Oh because it tastes nice.” It’s so stupid.[6.F1]

Vaping. Lot of that around now.[9.M2]

And Shisha as well… A lot of people at night go do shisha.[9.M4]

There’s a lot of that [vaping] going around.[9.F2]

Yeah, they all try to blow circles.[9.M4]

They even do it in class.[9.M3]

The teacher will be writing on the board and they’ll go and then put it in their bag. It’s funny.[9.M2]

3.2.3. Theme 3. Non-Smoking as a Sign of Good Physical, Social and Emotional Wellbeing

Substance Use

Sport and Fitness

And if you’re, for sport, if you’re in a rep team, or if you want to be big in a particular sport, sporting, ah, smoking. Won’t help you. It’ll just make you go down track, and it’ll just be bad for you, in anywhere you want to be.[7.M1]

Mental Health and Stress

I’d worry about what’s going on with their family and stuff. Start asking questions and that…there’s always a reason they’re doing it. Starting smoking. There’s always a reason.[5.M1]

A bit of both. Like I know the kids can’t come near me if I’m having a smoke. Cos I go outside and smoke, like “you stay inside, I’m out here smoking, leave me alone”. That’s why, five minutes for me to sit down and what I’ve been told, to have a smoke, you literally physically have to calm down because if you’re running, or if you’re walking around, you can’t smoke as well. Because your lungs are working to help you breathe. So, you’ve got to sit down, relax so then you can inhale the cigarette. It is forcing you to sit still and to relax, just so you can smoke a cigarette. That’s, yeah, so to have a cigarette you need to relax yourself, and yeah. I use that a lot.[11.F2]

Cos I’ve moved houses quite a lot too, since I was about eighteen. And I felt like it did worry me sometimes cos I didn’t know where I was go…I was couch hopping. I moved probably ten, fifteen times in the last couple of years. And right now, I’m in a transitional house, so I’m going to be moving again in a few weeks. Maybe, or it could be a month, or it could be two. I don’t know. So, it’s always the, the fear of not knowing where I’m going to be able to set up a permanent house for me and the kids, yeah, cos we haven’t had stability, we’ve moved, I’ve had the kids for about a year and a half now, and I’ve moved house three times. And we’ve got to move again, and again, and it’s just like, it stresses me out knowing that we can’t unpack all our stuff, just because we know that we’re going to be packing up again in a few months. And the kids, it’s not fair for the kids. They don’t get a chance to set up their rooms and they don’t feel like they’ve got a stable home. Hmm. So that does stress me out as well…That’s why I need my smokes.[11.F2]

Nicotine addiction

It comes under stress and, as well, because once you smoke, it, that’s a way that it could make your stress go away. And once you have that, like…[7.M1]

Once you start smoking…[7.M2]

Yeah, you get heaps addicted to it because it takes away the stress.[7.M1]

It could be like depressed. Like, feel like you harm yourself or whatever. And you need a smoke to calm you down or something. For example like yarndi. And then same thing, like if you’re stressed out, like going through court, family members in hospital crook. Just want to smoke, try and relax yourself. And then addicted, since you started, you’re just addicted. Ever since you started.[4.M1]

Family Illness

If you have a family member that’s sick and you see like, the pain and the stage that they’re going through. You feel like upset because you don’t want them to be like in that, in that stage, and it will help you not want to be like them, in the bed.[7.M1]

Like yes it would turn me off smoking, cos obviously all the bad stuff instilled into your body and stuff, but it would also make me want to smoke, just because of the stress factor involved. So, my family member’s dying, like there’s nothing I can do, it’s just it’s gotta stress me out and it’s my family’s all stressing. Like, we’re going to bury somebody, they’re dying. Um, it would just like put my stress levels right up. So I’d be smoking because of the stress, but I’d also be thinking like I need to quit because look what it’s done. I know that it’s doing more harm than good. Yeah. But, just at that time, you feel like you just need to have a smoke just to catch your breath, catch your thoughts, just stop for a second.[11.F2]

Relationships

…if you feeling stressed your family can help you instead of smoking. Cos when people are stressed they smoke, or if other people are stressed, then their family can help them.[7.M2]

Cos if you have a strong family, they’re behind you, you know, make you quit. Or you have a bad family that doesn’t give a shit, you know, they just keep lending you.[9.M3]

3.2.4. Theme 4. Importance of Individual Empowerment and Engagement for Being Smoke-Free

Disengagement, Boredom and Rejection of Harms

I think it’s also to do with trying to look cool. Um, I think you shouldn’t have to wreck your body to try and look cool.[9.F1]

They’re all doing it because they think it won’t happen to them, till like a couple of years…Yeah, they’re not worried about the long term, they worry about short term…they’re like you know, “I’ll quit after school”. When school finishes, they’ll quit, but they just keep going.[9.M2]

Empowerment, Engagement and Self-Efficacy

[I1] And you’ll be a non-smoker?

Yeah, I got a future career I’ve got to focus on. Can’t do that shit.[12.F2]

At parties. Do it a lot at parties when they’re drinking. They decide to smoke. I don’t really like it. I just walk away from them. Cos I don’t really like even seeing them doing that…I like being different. And I like, you have to be your own person, you don’t have to follow other people. I’d rather be a leader than a follower.[5.M1]

[I1] What makes you think “oh, I don’t want to do that”?

Just your future.[3.M3]

Ask them what their dreams are. And then if they say whatever, then you say you’re not going to get it by smoking.[3.M1]

3.3. Designing a Prevention Program

3.3.1. Objectives

3.3.2. Target Audience

3.3.3. Settings

3.3.4. Features

Be like, if they can get something like chemicals here, like I don’t know. Like show like how smoking works. Like you know how they have that one lung and the other lung, and how you press it and how slow the air released out of the smoked lung?[7.M2]

I reckon we should get some Elders that’s like grew up smoking and quit…Sit around and tell you how much, tell the young ‘uns you know, how it ruined them, and how they felt to inspire the little kids not to do it.[9.M2]

Because there are a lot of young mums around here, that smoke, well not just mums, single people too. Um, but yeah. Because there’s been a bit of talk about wanting, I’ve asked a few girls about the women’s group, and a lot of them want the women’s group back. I do. I’ve been saying that for years.[11.F2]

Well, like T-shirts are a very big deal around here. So if there was a deadly designed T-shirt at the end of it, that you get to keep, or maybe um, like a bag or something, that’s covered in Koori designs, that’d, that’d be a real eye catcher.[11.F2]

3.3.5. Timing

At least nine [months], yeah. Cos if I want to quit smoking, I know my behaviour’s going to change and I want her there with me, cos if she’s quitting too, she’s going to want me, and it’s just going to be like, we know we’ve got another couple of months to go together, and like. So by the time we full on quit, you know, it’d be good to make new friends too. Like there are other people who I don’t really talk to, but I’m pretty sure if we like go through this program, and meet up, and we’ll have something in common about quitting smoking … Just something constant over the next few weeks that we know is going to be in place. So like I’m not going to go cold turkey and then start smoking in a month or two, you know what I mean?[11.F2]

4. Discussion

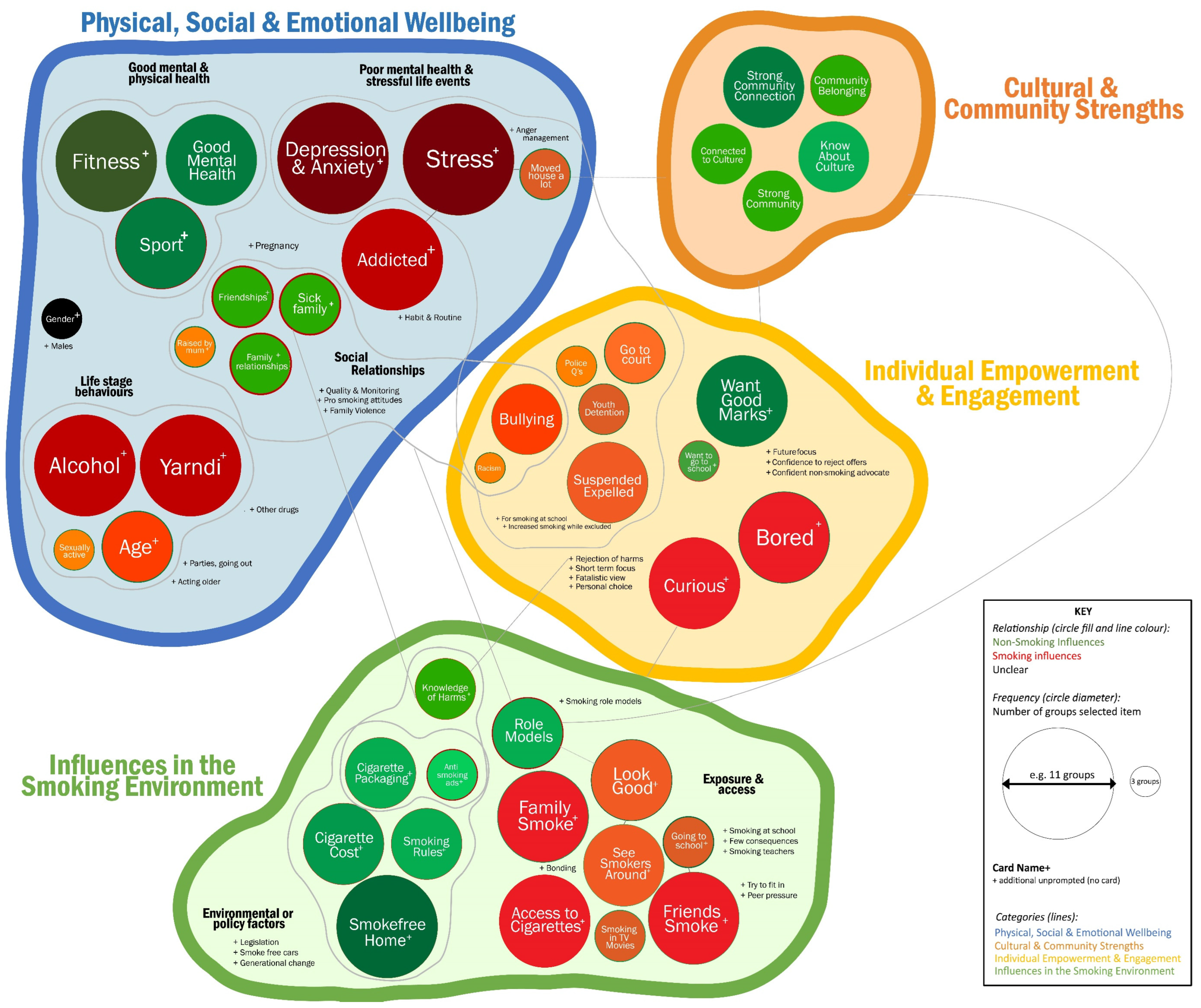

- Drawing strength from culture and community;

- How the smoking environment shapes attitudes and intentions;

- Non-smoking as a sign of good physical, social and emotional wellbeing;

- The importance of individual empowerment and engagement in being smoke-free.

4.1. Comparison to SEARCH Survey

4.2. Comparison to International Evidence

4.3. Comparison to Other Qualitative Studies

4.4. Recommendations for Programs

- Prevention programs must build cultural and community connections, empower young people and draw on community strengths. This essential approach is operationalised nationally in both the Australian Government’s ‘My Life My Lead report and Implementation Plan for the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013–2023′ (the Implementation Plan) [20,49]. Three out of four Implementation Plan goals for adolescent and youth health are tobacco related, with key strategies for success including pride in culture, support to make healthy choices and involving young people in the design of programs.

- Young community members must lead the development of prevention programs to build youth engagement and empowerment. Many study participants demonstrated they were eager and ready for such an opportunity. A potential model would see centralised decision making by an independent youth committee supported by and embedded within existing community-controlled organisational structures, providing leadership opportunities and enhancing self-determination while ensuring the program’s appeal and relevance.

- Interactive education about the harms of tobacco use is needed and should incorporate storytelling alongside youth-specific cessation support. It is important to counter the perception of safer, ‘light’ levels of smoking among ‘occasional’ or ‘social smokers’, as even lower levels of consumption increases cardiovascular disease risk [48]. The low knowledge of, but clear interest in, Australia’s history of tobacco use and the introduction, manipulation and control of Aboriginal people with tobacco during colonisation represents an important opportunity to counter the narrative of smoking as a personal choice or act of resistance, and to discuss the intergenerational transfer of smoking.

- Activities should be provided to address the broader underlying drivers of smoking and other risk behaviours, reducing stress and promoting good mental health and wellbeing. Although the previous iteration of the Tackling Indigenous Smoking program included a Healthy Lifestyles component with a focus on nutrition and physical activity and some relevant activities such as cooking classes, sport and cultural games [50], programs need to address broader determinants rather than the behaviours of multiple chronic disease risk factors simultaneously. There is a policy opportunity for greater funding flexibility for community organisations to design tobacco control programs that have the capacity to modify determinants of youth smoking, including boredom, disengagement, stress and poor mental health, through structured activities and supports that also build cultural and community connections.

- Community-level activities should be reinforced with strong national, mainstream tobacco control measures, including smoke-free legislation and social marketing campaigns, to continue the de-normalisation of smoking. Social marketing campaigns can play a key role in building knowledge of non-smoking expectations, increasing confidence to reject offers of cigarettes and reducing the appeal and status of cigarettes [51,52]. These campaigns are important for both reinforcing the attitudes and intentions of young Aboriginal non-smokers and for continuing to drive down broader population prevalence. Sustained national comprehensive tobacco control can ensure there is no erosion of the effect of community-level programs.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Institute of Health Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and Causes of Illness and Death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People 2018; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Thurber, K.A.; Banks, E.; Joshy, G.; Soga, K.; Marmor, A.; Benton, G.; White, S.L.; Eades, S.; Maddox, R.; Calma, T.; et al. Tobacco smoking and mortality among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults in Australia. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 942–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4714.0—National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, 2014–2015; ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2016. Available online: www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4714.0 (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4715.0—National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018–2019; ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2019. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/PrimaryMainFeatures/4715.0 (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Lovett, R.; Thurber, K.; Wright, A.; Maddox, R.; Banks, E. Deadly progress: Changes in Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adult daily smoking, 2004–2015. Public Health Res. Pract. 2017, 27, e2751742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox, R.; Thurber, K.A.; Calma, T.; Banks, E.; Lovett, R. Deadly news: The downward trend continues in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smoking 2004–2019. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2020, 44, 449–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heris, C.; Lovett, R.; Barrett, E.M.; Calma, T.; Wright, A.; Maddox, R. Deadly declines and diversity–understanding the variations in regional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smoking prevalence. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2022, 46, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4737.0—Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: Smoking Trends, Australia, 1994 to 2014–2015; ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2017. Available online: www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4737.0 (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Heris, C.; Eades, S.; Lyons, L.; Chamberlain, C.; Thomas, D. Changes in the age young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people start smoking, 2002–2015. Public Health Res. Pract. 2020, 30, e29121906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heris, C.L.; Guerin, N.; Thomas, D.P.; Eades, S.J.; Chamberlain, C.; White, V.M. The decline of smoking initiation among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander secondary students: Implications for future policy. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2020, 44, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Health 2018. Cat. No. AUS 221; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2018. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/australias-health-2018 (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use among Young People: A Report of the Surgeon General; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2012.

- Wood, L.; Greenhalgh, E.; Vittiglia, A.; Hanley-Jones, S. Chapter 5 Influences on the uptake and prevention of smoking. In Tobacco in Australia: Facts and Issues; Scollo, M.M., Winstanley, M.H., Eds.; Cancer Council Victoria: Melbourne, Australia, 2019; Available online: www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-5-uptake (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- van der Sterren, A.; Greenhalgh, E.; Knoche, D.; Winstanley, M. Chapter 8 Tobacco use among Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders. In Tobacco in Australia: Facts and Issues; Scollo, M.M., Winstanley, M.H., Eds.; Cancer Council Victoria: Melbourne, Australia, 2016; Available online: www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-8-aptsi (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Thomas, D.P.; Briggs, V.; Anderson, I.P.S.; Cunningham, J. The social determinants of being an Indigenous non-smoker. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2008, 32, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Burden of Tobacco Use in Australia: Australian Burden of Disease Study 2015. Cat. No. BOD 20; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2019. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/burden-of-disease/burden-of-tobacco-use-in-australia (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Briggs, V.L.; Lindorff, K.J.; Ivers, R.G. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and tobacco. Tob. Control 2003, 12 (Suppl. 2), ii5–ii8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colonna, E.; Maddox, R.; Cohen, R.; Marmor, A.; Doery, K.; Thurber, K.A.; Thomas, D.; Guthrie, J.; Wells, S.; Lovett, R. Review of tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Aust. Indig. HealthBulletin 2020, 20, 2–61. [Google Scholar]

- Thurber, K.; Colonna, E.; Jones, R.; Gee, G.; Priest, N.; Cohen, R.; Williams, D.; Thandrayen, J.; Calma, T.; Lovett, R.; et al. Prevalence of Everyday Discrimination and Relation with Wellbeing among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Adults in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health. My Life My Lead—Opportunities for Strengthening Approaches to the Social Determinants and Cultural Determinants of Indigenous Health: Report on the National Consultations December 2017; ACT: Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2017.

- Chamberlain, C.; Perlen, S.; Brennan, S.; Rychetnik, L.; Thomas, D.; Maddox, R.; Alam, N.; Banks, E.; Wilson, A.; Eades, S. Evidence for a comprehensive approach to Aboriginal tobacco control to maintain the decline in smoking: An overview of reviews among Indigenous peoples. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heris, C.; A Thurber, K.; Wright, D.; Thomas, D.; Chamberlain, C.; Gubhaju, L.; Sherriff, S.; McNamara, B.; Banks, E.; Smith, N.; et al. Staying smoke-free: Factors associated with nonsmoking among urban Aboriginal adolescents in the Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health (SEARCH). Health Promot. J. Austr. 2021, 32, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Heris, C.L.; Gubhaju, L.; Eades, F.; Williams, R.; Davis, K.; Whitby, J.; Hunt, K.; Chimote, N.; Eades, S.J. Young Aboriginal people in Australia who have never used marijuana in the ‘Next Generation Youth Well-being study’: A strengths-based approach. Int. J. Drug Policy 2021, 95, 103258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heris, C.; Guerin, N.; Thomas, D.; Chamberlain, C.; Eades, S.; White, V.M. Smoking behaviours and other substance use among Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian secondary students, 2017. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2021, 40, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heris, C.; Scully, M.; Chamberlain, C.; White, V. E-cigarette use and the relationship to smoking among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous Australian Secondary Students, 2017. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2022, 46, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heris, C.L.; Chamberlain, C.; Gubhaju, L.; Thomas, D.P.; Eades, S.J. Factors influencing smoking among Indigenous adolescents aged 10–24 years living in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States: A systematic review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 22, 1946–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, V.; Westphal, D.W.; Earnshaw, C.; Thomas, D.P. Starting to smoke: A qualitative study of the experiences of Australian Indigenous youth. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosh, S.; Hawkins, K.; Skaczkowski, G.; Copley, D.; Bowden, J. Tobacco use among urban Aboriginal Australian young people: A qualitative study of reasons for smoking, barriers to cessation and motivators for smoking cessation. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2015, 21, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivankova, N.V.; Creswell, J.W.; Stick, S.L. Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice. Field Methods 2006, 18, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryer, C.S.; Seaman, E.L.; Clark, R.S.; Clark, V.L.P. Mixed methods research in tobacco control with youth and young adults: A methodological review of current strategies. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, S.; Albert, M.; Kuper, A.; Hodges, B.D. Why use theories in qualitative research? BMJ 2008, 337, a949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laycock, A.; Walker, D.; Harrison, N.; Brands, J. Part A: Indigenous Health Research in Context. In Researching Indigenous Health: A Practical Guide for Researchers; The Lowitja Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bessarab, D.; Ng’Andu, B. Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. Int. J. Crit. Indig. Stud. 2010, 3, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Fredericks, B.; Mills, K.; Anderson, D. “Yarning” as a method for community-based health research with indigenous women: The indigenous women’s wellness research program. Health Care Women Int. 2014, 35, 1216–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, J. The methodology of Focus Groups: The importance of interaction between research participants. Sociol. Health Illn. 1994, 16, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The SEARCH Investigators. The Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health (SEARCH): Study protocol. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci, E. “Focus Groups Can Be Fun”: The Use of Activity-Oriented Questions in Focus Group Discussions. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1422–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Willis, K.; Hughes, E.; Small, R.; Welch, N.; Gibbs, L.; Daly, J. Generating best evidence from qualitative research: The role of data analysis. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2007, 31, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; APA Handbooks in Psychology ®; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Flay, B.R. Theory of Triadic Influence. In Encyclopedia of Health and Behavior; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 715–718. Available online: http://sk.sagepub.com/reference/behavior (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- Flay, B.R.; Petraitis, J. A new theory of health behavior with implications for preventive interventions. Adv. Med. Sociol. 1994, 4, 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.P.; Davey, M.E.; Panaretto, K.S.; van der Sterren, A.E. Cannabis use among two national samples of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tobacco smokers. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018, 37, S394–S403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, V.; Thomas, D.P. Smoking behaviours in a remote Australian Indigenous community: The influence of family and other factors. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 1708–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passey, M.E.; Gale, J.T.; Sanson-Fisher, R.W. "It’s almost expected": Rural Australian Aboriginal women’s reflections on smoking initiation and maintenance: A qualitative study. BMC Womens Health 2011, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leavy, J.; Wood, L.; Phillips, F.; Rosenberg, M. Try and try again: Qualitative insights into adolescent smoking experimentation and notions of addiction. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2010, 21, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, E.; Joshy, G.; Korda, R.J.; Stavreski, B.; Soga, K.; Egger, S.; Day, C.; Clarke, N.E.; Lewington, S.; Lopez, A.D. Tobacco smoking and risk of 36 cardiovascular disease subtypes: Fatal and non-fatal outcomes in a large prospective Australian study. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health. Implementation Plan for the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013–2023; ACT: Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2015.

- Upton, P.; Davey, R.; Evans, M.; Mikhailovich, K.; Simpson, L.; Hacklin, D. Tackling Indigenous Smoking and Healthy Lifestyle Programme Review; ACT: University of Canberra: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- White, V.M.; Durkin, S.J.; Coomber, K.; Wakefield, M.A. What is the role of tobacco control advertising intensity and duration in reducing adolescent smoking prevalence? Findings from 16 years of tobacco control mass media advertising in Australia. Tob. Control 2015, 24, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, M.A.; Loken, B.; Hornik, R.C. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet 2010, 376, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interview | Sex | Age Group | Site | Smoking Status | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 18+ | 1 | Non-smoking | 1 |

| 2 | Female | 18+ | 1 | Smoking/ex | 3 |

| 3 | Male | 12–15 | 1 | Non-smoking/ex | 3 |

| 4 | Male | 18+ | 1 | Smoking | 1 |

| 5 | Male | 18+ | 1 | Non-smoking | 1 |

| 6 | Mixed | 12–15 | 1 | Non-smoking | 3 |

| 7 | Mixed | 12–17 | 2 | Non-smoking | 3 |

| 8 | Mixed | 12–17 | 2 | Non-smoking | 3 |

| 9 | Mixed | 12–17 | 2 | Non-smoking/ex | 7 |

| 10 | Female | 12–18+ | 2 | Mixed | 2 |

| 11 | Mixed | 12–18+ | 2 | Smoking | 3 |

| 12 | Female | 12–17 | 2 | Non-smoking | 2 |

| Overall | 17 Female, 15 Male | 23 < 18 9 18+ | 7 Smoking 25 Non-smoking (ex, trialled, never) | 32 |

| 1. Drawing Strength from Culture & Community | ||

| Non-Smoking | Unclear/Both | Smoking |

| Strong community connection Community belonging Know about culture Connection to culture Strong community | ||

| 2. How the smoking environment shapes attitudes and intentions | ||

| Non-Smoking | Unclear/Both | Smoking |

| Smoke-free home * Cigarette cost * Smoking rules * Cigarette packaging * Anti-smoking ads * Role models +Legislation +Smoke-free cars +Generational change Knowledge of smoking harms * | Family smoke * +Bonding +Pro-smoking attitudes Friends smoke * +Try to fit in +Peer pressure +Smoking at school +Few consequences at school +Smoking teachers Access to cigarettes * See smokers around * +Smoking role models Look good * Smoking in TV/movies | |

| 3. Non-smoking as a sign of good physical, social and emotional wellbeing | ||

| Non-Smoking | Unclear/Both | Smoking |

| Fitness * Sport * Good mental health +Pregnancy +Quality of social relationships | Live with/raised by mum * Sick family * Friendships * Family relationships * Sex/gender * | Depression and anxiety * Stress * +Anger management +More smoking while excluded Moved house a lot Alcohol * Yarndi * +other drugs Age * +Acting older +Going out, going to parties Being sexually active Addiction * +Habit & routine +Family violence +Males |

| 4. The importance of individual empowerment and engagement in being smoke-free | ||

| Non-Smoking | Unclear/Both | Smoking |

| Want good marks * Want to go to school * +Future focus +Self-efficacy to g no +Confident advocacy against smoking | Bullying Racism Curious * Boredom * +Personal choice +Rejection of harms +Short-term focus +Fatalistic view +Low parental monitoring Go to court Youth detention Questioned by police Suspension/expulsion Going to school * | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heris, C.L.; Cutmore, M.; Chamberlain, C.; Smith, N.; Simpson, V.; Sherriff, S.; Wright, D.; Slater, K.; Eades, S. Don’t Follow the Smoke—Listening to the Tobacco Experiences and Attitudes of Urban Aboriginal Adolescents in the Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health (SEARCH). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054587

Heris CL, Cutmore M, Chamberlain C, Smith N, Simpson V, Sherriff S, Wright D, Slater K, Eades S. Don’t Follow the Smoke—Listening to the Tobacco Experiences and Attitudes of Urban Aboriginal Adolescents in the Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health (SEARCH). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054587

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeris, Christina L., Mandy Cutmore, Catherine Chamberlain, Natalie Smith, Victor Simpson, Simone Sherriff, Darryl Wright, Kym Slater, and Sandra Eades. 2023. "Don’t Follow the Smoke—Listening to the Tobacco Experiences and Attitudes of Urban Aboriginal Adolescents in the Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health (SEARCH)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054587

APA StyleHeris, C. L., Cutmore, M., Chamberlain, C., Smith, N., Simpson, V., Sherriff, S., Wright, D., Slater, K., & Eades, S. (2023). Don’t Follow the Smoke—Listening to the Tobacco Experiences and Attitudes of Urban Aboriginal Adolescents in the Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health (SEARCH). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4587. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054587