Effectiveness of Prevention Interventions Using Social Marketing Methods on Behavioural Change in the General Population: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

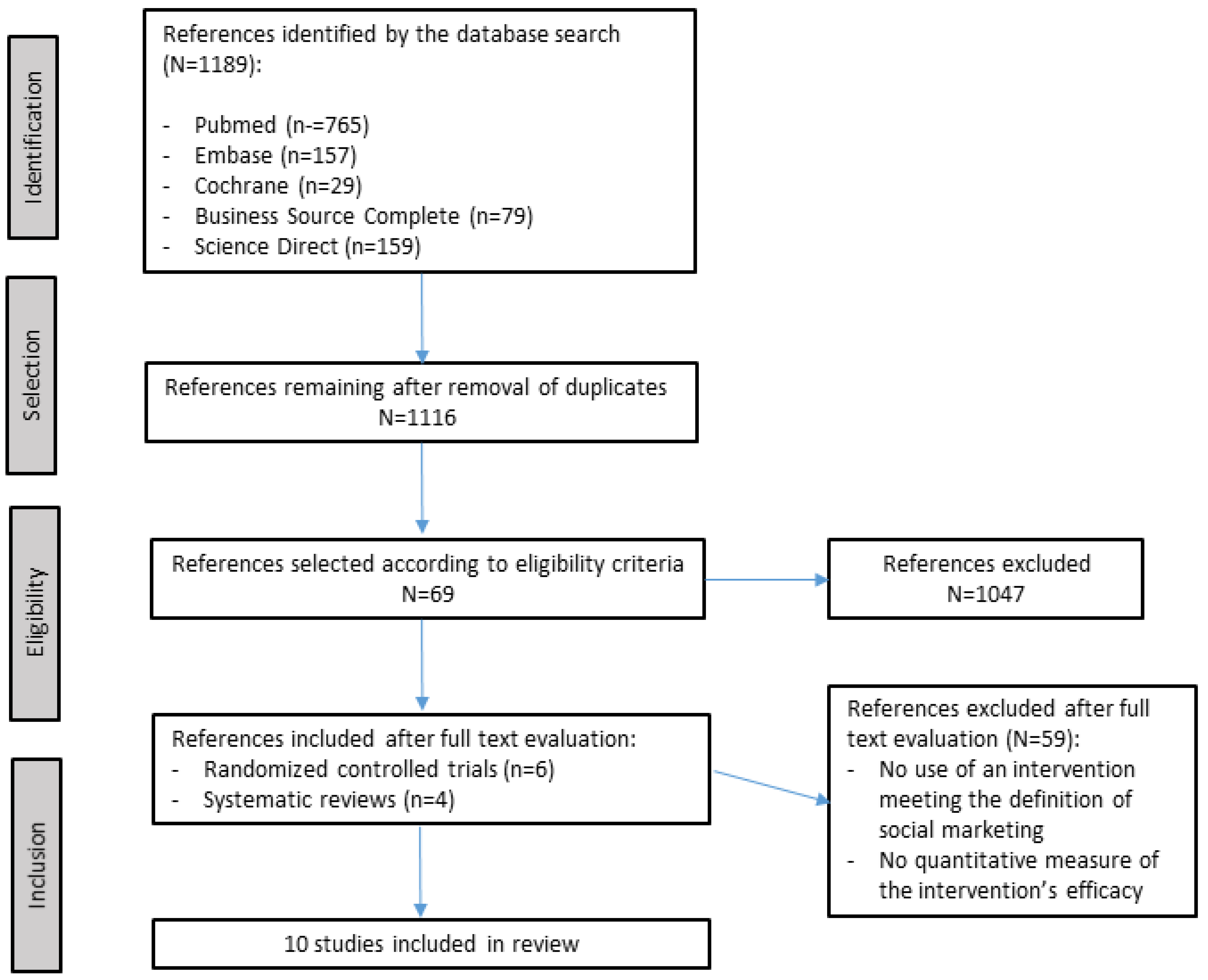

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- randomized, controlled trials, or systematic reviews;

- use of social marketing as the predominant feature of the study; defined as “a process that applies marketing principles and techniques to create, communicate and deliver value in order to infuence target audience behaviours that benefit society (e.g., public health, safety, the environment and communities) as well as the target audience” [19];

- with analysis of the efficacy of social marketing interventions (i.e., assessment of the effect of preventive interventions using social marketing techniques, on the willingness and/or ability to change potentially harmful and/or undesirable behaviours);

- performed among the general population (aged 14–65 years).

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Assessment of Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias

3. Results

3.1. Results of Randomized Trials

3.2. Results of Systematic Reviews

3.3. Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews

4. Discussion

4.1. Quality of the Studies

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liao, C.H. Evaluating the Social Marketing Success Criteria in Health Promotion: A F-DEMATEL Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, É. Du changement de comportement à l’action sur les conditions de vie. St. Publique 2013, S2, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockerham, W.C. Health lifestyle theory and the convergence of agency and structure. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2005, 46, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Non-Communicable Diseases. Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Hastings, G.; Haywood, A. Social marketing and communication in health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 1991, 6, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, R. Social marketing in healthcare. Australas. Med. J. 2011, 4, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, W.D. How social marketing works in health care. BMJ 2006, 332, 1207–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotler, P.; Zaltman, G. Social Marketing: An Approach to Planned Social Change. J. Mark. 1971, 35, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carins, J.E.; Rundle-Thiele, S.R. Eating for the better: A social marketing review (2000–2012). Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1628–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.R.; Kotler, P. Social Marketing: Behavior Change for Social Good, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. 642. [Google Scholar]

- Stead, M.; Hastings, G.; McDermott, L. The meaning, Effectiveness and Future of Social Marketing. Obes. Rev. 2007, 8 (Suppl. 1), 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, K. Understanding Behaviour Change. How to Apply Theories of Behaviour Change to SEWeb and Related Public Engagement Activities. Report for SEWeb LIFE10 ENV-UK-000182. The James Hutton Institute. 2012. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267506263_Understanding_behaviour_change_How_to_apply_theories_of_behaviour_change_to_SEWeb_and_related_public_engagement_activities (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Karpen, I.O.; Bove, L.L.; Lukas, B.A. Linking Service-Dominant Logic and Strategic Business Practice:A Conceptual Model of a Service-Dominant Orientation. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.M.; Mathijssen, J.J.; van Bon-Martens, M.J.; van Oers, H.A.; Garretsen, H.F. Effectiveness of alcohol prevention interventions based on the principles of social marketing: A systematic review. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2013, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchioli, A. Social marketing and efficacy of public health prevention campaigns: Contributions and implications of recent models of persuasive communication. Mark. Manag. 2006, 6, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallopel-Morvan, K. Social Marketing and Critical Social Marketing: What Benefits for Public Health? Les Trib. Sante 2014, 45, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3 (updated February 2022); Cochrane: 2022. Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Lee, N.R.; Kotler, P. Social Marketing: Influencing Behaviors for Good, 4th ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savovic, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velema, E.; Vyth, E.L.; Hoekstra, T.; Steenhuis, I.H.M. Nudging and social marketing techniques encourage employees to make healthier food choices: A randomized controlled trial in 30 worksite cafeterias in The Netherlands. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmath, D.; Winterstein, A.P. A Social-Marketing Intervention and Concussion-Reporting Beliefs. J. Athl. Train. 2020, 55, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJong, W.; Schneider, S.K.; Towvim, L.G.; Murphy, M.J.; Doerr, E.E.; Simonsen, N.R.; Mason, K.E.; Scribner, R.A. A multisite randomized trial of social norms marketing campaigns to reduce college student drinking. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2006, 67, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, M.; MacKintosh, A.M.; Findlay, A.; Sparks, L.; Anderson, A.S.; Barton, K.; Eadie, D. Impact of a targeted direct marketing price promotion intervention (Buywell) on food-purchasing behaviour by low income consumers: A randomised controlled trial. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 30, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamada, M.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Abe, T.; Taguri, M.; Inoue, S.; Ishikawa, Y.; Harada, K.; Lee, I.M.; Bauman, A.; Miyachi, M. Community-wide promotion of physical activity in middle-aged and older Japanese: A 3-year evaluation of a cluster randomized trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamada, M.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Abe, T.; Taguri, M.; Inoue, S.; Ishikawa, Y.; Bauman, A.; Lee, I.M.; Miyachi, M.; Kawachi, I. Community-wide intervention and population-level physical activity: A 5-year cluster randomized trial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coz, S.; Kamin, T. Systematic Literature Review of Interventions for Promoting Postmortem Organ Donation From Social Marketing Perspective. Prog. Transplant. 2020, 30, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaid, L.; Riddell, J.; Teal, G.; Boydell, N.; Coia, N.; Flowers, P. The Effectiveness of Social Marketing Interventions to Improve HIV Testing Among Gay, Bisexual and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 2273–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noar, S.M.; Palmgreen, P.; Chabot, M.; Dobransky, N.; Zimmerman, R.S. A 10-year systematic review of HIV/AIDS mass communication campaigns: Have we made progress? J. Health Commun. 2009, 14, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondé, J.; Girandola, F. “Appealing to fear” in order to persuade? A review of the literature and research perspectives. L’Année Psychol. 2016, 116, 67–103. [Google Scholar]

- Witte, K.; Allen, M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ. Behav. 2000, 27, 591–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cismaru, M.; Lavack, A.M.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.; Dorsch, K.D. Understanding Health Behavior: An Integrated Model for Social Marketers. Soc. Mark. Q. 2008, 14, 2–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Country, Year [Ref] | Type of Communication | Target Population | Endpoint | Key Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Velema, Netherlands, 2018 [22] | Nudging | An amount of 30 worksite cafeterias | Sales data for the targeted food products Compliance with the intervention protocol | Significant positive effect of the intervention on the volume of sales for three of the seven targeted product groups An amount of 77% of the eligible strategies were implemented correctly in the intervention cafeterias |

| Warmath, Greece, 2020 [23] | Three video interventions using three fact sheets (one for each of the three interventions) | An amount of 468 competitive athletes in a US university who engaged in 1 or 46 sports with concussion risk | Positive and negative beliefs regarding concussion reporting | Exposure to consequence-based social marketing significantly increased positive reporting beliefs and significantly decreased negative reporting beliefs as compared to the traditional or revised symptom-education conditions. |

| DeJong, United States of America, 2009 [24] | Social norms marketing campaigns about student drinking (norms and volume) | Cross-sectional survey in 2771 students at baseline and 2939 at three years in 18 higher education institutions | Perceptions of student drinking levels and level of alcohol consumption | Exposure to the SNM campaign was significantly associated with lower perceptions of student drinking levels and lower alcohol consumption. A moderate mediating effect of normative perceptions on student drinking was found. Suggestion of a dose-response relationship. |

| Stead, United Kingdom, 2017 [25] | Direct marketing price promotion combined with healthy eating advice and recipes for “less healthy” shoppers | An amount of 53,367 customers in a supermarket chain in he UK | Sales data from before, during and after the promotion | Increase in the proportion of customers buying promoted products in the intervention month for four out of five products. Significantly higher uptake in the promotion group in the intervention group compared to the expected average based on other months. Effects were not sustained beyond the intervention period. |

| Kamada, Japan, 2015 [26] | Community-wide intervention with cluster randomization using flyers, leaflets, posters, newsletters, banners and radio, plus outreach health education during community events, plus social support. | Community dwellers aged 49 to 70 years in 12 Japanese communities | Change in regular aerobic, flexibility, and/or muscle strengthening activities, evaluated at the individual level. | No significant effect of the intervention on the proportion of adults who reached recommended levels of aerobic, flexibility, or muscle-strengthening activities at three years compared to controls. |

| Kamada, Japan, 2018 [27] | Community-wide intervention with cluster randomization using flyers, leaflets, posters, newsletters, banners and radio, plus outreach health education during community events, plus social support. | Community dwellers aged 49 to 70 years in 12 Japanese communities | Change in regular aerobic, flexibility, and/or muscle strengthening activities, evaluated at the individual level. | At five years, compared to control communities, the proportion of adults achieving recommended levels of physical activity increased in intervention communities. The intervention was effective in promoting all three types of exercise individually, whereas a bundled approach promoting all three types simultaneously was not found to be effective. Pain intensity was found to decrease for the shoulder (in the intervention and control groups) and lower back (intervention group only). |

| Author [Ref] | Type of Communication | Target Population | Endpoint | Key Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coz, Slovenia, 2020 [28] | Mass media, multichannel approaches, direct (interpersonal face-to-face) communication | An amount of 32 articles describing 36 interventions promoting organ donation | Increasing donor registration rates was the most common primary behavioral objective of the interventions | There was a significant relationship between the use of social marketing benchmark criteria in the design of the intervention, and the success of the intervention. Interventions that employed six or seven (out of seven) criteria reported greater success in achieving intervention objectives. |

| McDaid, United Kingdom, 2019 [29] | Videos, television, radio, web-based advertisements, cinema and newspaper advertisements, posters, leaflets, etc. | An amount of 19 studies of interventions to increase HIV testing among men who have sex with men | Rate of HIV testing | Five cross-sectional and one randomized trial reported increased HIV testing after the intervention, providing evidence for the effectiveness of social marketing/mass media interventions to increase HIV testing. Risk of bias was high. |

| Carins, Australia, 2014 [9] | Social marketing processes incorporating individual and social activities | An amount of 34 empirical studies that self-reported as social marketing healthy eating interventions | Presence of social marketing benchmark criteria | Among sixteen studies with social marketing as a planned, consumer-oriented process, only six met all six benchmark criteria; the mean number of criteria was five. These 16 studies that met the definition of social marketing were more effective in achieving behavioural change than the 18 studies that self-reported as social marketing, but did not meet social marketing criteria. |

| Noar, United States of America, 2009 [30] | Mass communication campaigns focused on sexual behaviour, HIV testing, or both. | An amount of 38 HIV/AIDS campaign evaluation articles describing 34 distinct campaigns in 23 countries | Campaign design, and evaluation measures (change in behaviours or intentions) | There has been increasing use of the several strategies over time, including targeting defined audiences; designing campaigns around changes in behaviour (not knowledge); use of behavioural theories; high message exposure; stronger research design and measure of behavioural change (or intentions) as outcome assessments. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roger, A.; Dourgoudian, M.; Mergey, V.; Laplanche, D.; Ecarnot, F.; Sanchez, S. Effectiveness of Prevention Interventions Using Social Marketing Methods on Behavioural Change in the General Population: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4576. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054576

Roger A, Dourgoudian M, Mergey V, Laplanche D, Ecarnot F, Sanchez S. Effectiveness of Prevention Interventions Using Social Marketing Methods on Behavioural Change in the General Population: A Systematic Review of the Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4576. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054576

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoger, Aude, Mikael Dourgoudian, Virginie Mergey, David Laplanche, Fiona Ecarnot, and Stéphane Sanchez. 2023. "Effectiveness of Prevention Interventions Using Social Marketing Methods on Behavioural Change in the General Population: A Systematic Review of the Literature" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4576. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054576

APA StyleRoger, A., Dourgoudian, M., Mergey, V., Laplanche, D., Ecarnot, F., & Sanchez, S. (2023). Effectiveness of Prevention Interventions Using Social Marketing Methods on Behavioural Change in the General Population: A Systematic Review of the Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4576. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054576