Association between Sarcopenia, Falls, and Cognitive Impairment in Older People: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

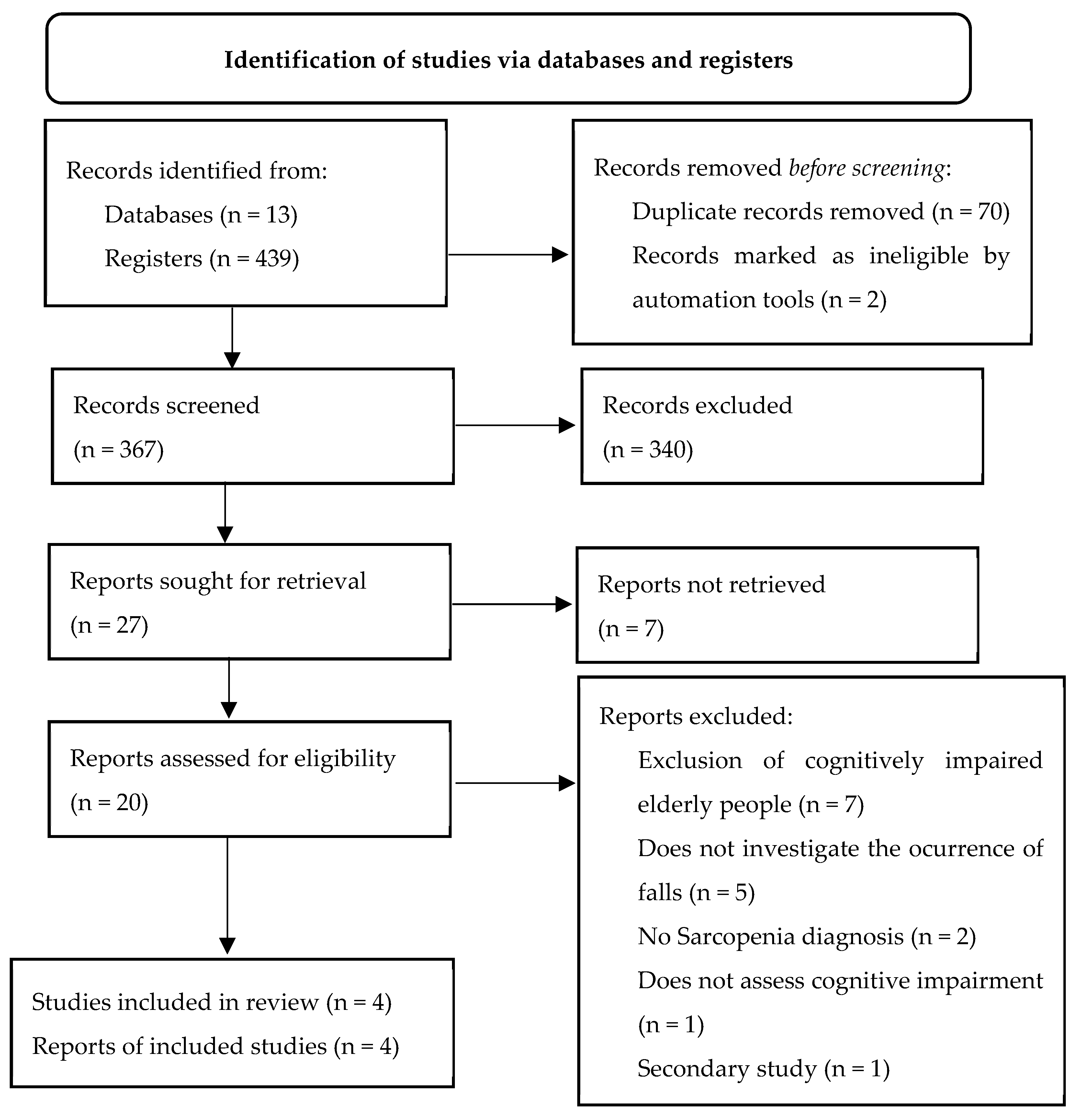

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nações Unidas. Envelhecimento. 2022. Available online: https://unric.org/pt/envelhecimento/ (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- World Health Organization. Envelhecimento Saudavel; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.paho.org/pt/envelhecimento-saudavel (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Zengarini, E.; Giacconi, R.; Mancinelli, L.; Riccardi, G.R.; Astellani, D.; Vetrano, D.L.; Onder, G.; Volpato, S.; Ruggiero, C.; Fabbietti, P.; et al. Prognosis and interplay of cognitive impairment and sarcopenia in older adults discharge from acute care hospitals. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério de Salud y Protección Social. Envejecimiento y Vejez; Ministério de Salud y Protección Social: Cali, Colombia, 2020. Available online: https://minsalud.gov.co/proteccionsocial/promocion-social/Paginas/envejecimiento-vejez.aspx (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Bektas, A.; Schurman, S.H.; Sen, R.; Ferrucci, L. Aging, inflammation and the environment. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 105, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carapeto, P.V.; Aguayo-Mazzucato, C. Effects of exercise on cellular and tissue aging. Ageing 2021, 13, 14522–14543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyere, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised european consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandre, T.S.; Duarte, Y.A.O.; Santos, J.L.F.; LEbrão, M.L. Prevalence and associated factors of sarcopenia, dynapenia, and sarcodynapenia in community-dwelling elderly in São Paulo—SABE study. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2018, 21 (Suppl. S2), E180009. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Barría, H.; Aguilera-Eguia, R.; González-Wong, C. The role of vitamin D in the prevention of falls among subjects with sarcopenia. Rev. chil. Nutr. 2018, 45, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, C.W.A.; Martínez, F.F.E.; Olaya, S.L.C. Sarcopenia, a new pathology that impacts old age. Rev. ACE 2018, 5, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Falls; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Kirk, B.; Zanker, J.; Hassan, E.B.; Bird, S.; Brennan-Olsen, S.; Duque, G. Sarcopenia definitions and outcomes consortium (SDOC) criteria are strongly associated with malnutrition, depression, falls, and fractures in high-risk older persons. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivan, N.F.M.; Singh, D.K.A.S.; Shahar, S.; Wen, G.J.; Rajab, N.F.; Din, N.C.; Mahadzir, H.; Kamaruddin, M.Z.A. Cognitive frailty is a robust predictor of falls, injuries, and disability among community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides-Caro, C.A. Deterioro cognitivo en el adultomayor. Rev. Mex. Anestesiol. 2017, 40, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, T.C.; Chen, W.L.; Wu, L.W.; Chang, Y.W.; Kao, T.W. Sarcopenia and cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 2695–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.S.Y.; Reijnierse, E.M.; Pham, V.K.; Trappenburg, M.C.; Lim, W.K.; Meskers, C.G.M.; Maier, A.B. Sarcopenia and its association with falls and fractures in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Caquexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: North Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/ageing#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Chen, L.K.; Woo, J.; Assantachai, P.; Zhang, T.; Akishita, M.; Arai, H. Asian working group for sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web mobile aoo for systematic reviews. Methodology 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar]

- JBI. Critical Appraisal Tools, Adelaide, Australia. 2020. Available online: https://sumari.jbi.global/ (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Santos, D.M. Prevalência de Sarcopenia e Fatores Associados em Idosos de um Centro de Referência em Salvador—Bahia. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, Brazil, 2021; 60p. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.; Kim, M.; Won, C.W. Common and different characteristics among combinations of physical frailty and sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults: The Korean frailty and aging cohort study. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2021, 22, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Chen, T.; Shan, Q.; Hu, B.; Zhao, M.; Deng, X.; Zuo, J.; Hu, Y.; Fan, L. Sarcopenia is associated with cognitive decline and falls but not hospitalization in community-dwelling oldest old in China: A cross sectional study. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e919894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landi, F.; Liperoti, R.; Russo, A.; Giovannini, S.; Tosato, M.; Capoluongo, E.; Bernabei, R.; Onder, G. Sarcopenia as a risk factor for falls in elderly individuals: Results from the ilSIRENTE study. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianov, L.; De Both, M.; Chawla, M.K.; Rani, A.; Kennedy, A.J.; Piras, I.; Day, J.J.; Siniard, A.; Kumar, A.; Sweatt, J.D.; et al. Hippocampal transcriptomic profiles: Subfield vulnerability to age and cognitive impairment. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fhon, J.R.S.; Rodrigues, R.A.P. Falls and demographic and clinical factors in older adults: Follow-up study. Enfermería Glob. 2021, 61, 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yan, E.; Yang, L.; Yang, C.; Liu, C. Sarcopenia and perioperative management of elderly surgical patients. Front. Biosci. 2021, 30, 882–894. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.; Cheol, M. Prevalence of Sarcopenia Among the Elderly in Korea: A Meta-Analysis. Prev. Med. Public Health 2021, 54, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.V.; Hsu, T.H.; Wu, W.T.; Huang, H.C.; Han, D.S. Association between sarcopenia and cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 1164.e7–1164.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, H.; Makizako, H.; Doi, T.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Suimada, H. Associations of skeletal muscle mass lower-extremity functioning and cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older people in Japan. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2019, 23, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dam, O.S.; Aleman, A.; Vries, W.R.; Deijen, J.B.; van der Veen, E.Z.; Haan, E.H.; Koppeschaar, H.P. Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor I and cognitive function in adults. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2000, 10 (Suppl. B), S69–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, S.J.; Yu, L.J. Oxidative Stress, Molecular Inflammation and Sarcopenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 1509–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoene, D.; Kiesswetter, E.; Cornel, C.S.; Freiberger, E. Musculoskeletal factors, sarcopenia and falls in old age. Z Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 52, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadelha, A.B.; Cainshelboim, B.; Ferreira, A.P.; Neri, S.G.R.; Bottaro, M.; Lima, R.M. Stages of sarcopenia and the incidence of falls in older women: A prospective study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 79, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Stoppoing Elderly Accodents, Deaths and Injuries. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/index.html (accessed on 30 January 2023).

| Database | Search Strategy | Results |

|---|---|---|

| BVS | ((mh:(“Acidentes por Quedas”)) OR (“Acidentes por Quedas” OR “Accidental Falls” OR “Accidentes por Caídas”)) AND ((mh:(Idoso)) OR (Idoso OR Aged OR Anciano)) AND ((mh:(Sarcopenia)) OR (Sarcopenia)) AND ((mh:(“Disfunção Cognitiva”)) OR (“Disfunção Cognitiva” OR “Cognitive Dysfunction” OR “Disfunción Cognitiva”)) | 9 |

| PUBMED | (((“Accidental Falls”[Mesh] OR “Accidental Falls” OR “Accidental Fall”) AND (“Aged”[Mesh] OR Aged)) AND (“Sarcopenia”[Mesh] OR Sarcopenia)) AND (“Cognitive Dysfunction”[Mesh] OR “Cognitive Dysfunction”) | 7 |

| CINAHL | ((MH “Accidental Falls”) OR “Accidental Falls” OR “Accidental Fall”) AND ((MH “Aged”) OR Aged) AND ((MH “Sarcopenia”) OR Sarcopenia) AND ((((MH “Cognition Disorders”) OR “Cognitive Disorders” OR “Cognitive Dysfunction”)) OR ((MH “Cognitive Aging”) OR “Cognitive Aging”))) | 11 |

| EMBASE | (falls OR “accidental falls” OR falling) AND (Aged) AND (Sarcopenia) AND (“cognitive defect” OR “cognitive dysfunction” OR “cognitive disorder” OR “cognitive disorders”) | 82 |

| SCOPUS | ((fall*) AND (aged) AND (sarcopenia) AND ({cognitive defect} OR {cognitive dysfunction} OR {cognitive disorder} OR {cognitive disorders})) | 72 |

| Web of Science | (fall*) AND (Aged) AND (Sarcopenia) AND (“cognitive defect” OR “cognitive dysfunction” OR “cognitive disorder” OR “cognitive disorders”) | 9 |

| Google Scholar | (“Accidental Falls”) AND (Aged) AND (Sarcopenia) AND (“cognitive defect” OR “cognitive dysfunction” OR “cognitive disorder” OR “cognitive disorders”) | 97 |

| CAPES Theses and Dissertations | (Queda OR Quedas) AND Idoso AND Sarcopenia | 29 |

| Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) | (“Accidental Falls”) AND (Aged) AND (Sarcopenia) | 38 |

| EBSCO Open Dissertations | (“Accidental Falls”) AND (Aged) AND (Sarcopenia) | 51 |

| DART-e | (Fall OR Falls) AND (Aged) AND (Sarcopenia) | 3 |

| Brazilian Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations | (Fall OR Falls) AND (Aged) AND (Sarcopenia) | 18 |

| ACS Guide to Scholarly Communication | (Fall OR Falls) AND (Aged) AND (Sarcopenia) | 13 |

| Total Records | 439 | |

| Author, Year | Population | Age, Sex | Type of Study | Instruments | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santos, 2021 [23] | 413 elderly patients receiving care at the geriatrics and gerontology outpatient unit | ≥60 years old, of both sexes, with a prevalence of females | Cross-sectional | EWGSOP2 criteria *** (handgrip strength—SAEHAN digital dynamometer, Gait Speed Test, Body Mass Index) Report of falls over the last 3 months Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) | Sarcopenia - Probable: 57.9% - Confirmed: 6.1% - Severe: 6.8% Falls: 18.4% Cognitive Impairment: 25.7% |

| Lee et al., 2021 [24] | 2028 elderly outpatients | ≥70 years, of both sexes | Retrospective longitudinal | AWGS Criteria * 2014 and 2019 (Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, digital handgrip dynamometer, usual gait speed of 4 m) Report of falls over the last 12 months MMSE | Sarcopenia: 17.5% (AWGS 2019) 9.1% (AWGS 2014) Falls: 23.1% of elderly people with sarcopenia Cognitive Impairment: 24.1% |

| Xu et al., 2020 [25] | 582 elderly people from the community | ≥80 years, of both sexes, with a prevalence of females | Cross-sectional | AWGS Criteria * (Handgrip strength—dynamometer, usual gait speed, electrical bioimpedance) Report of falls over the last 12 months Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | Sarcopenia: 26.6% Falls: 18.1% Cognitive Impairment: 60.8% |

| Landi et al., 2012 [26] | 260 elderly people from the community | ≥80 years, of both sexes, with a prevalence of female | Prospective longitudinal | EWGSOP Criteria ** (middle arm muscle circumference, usual gait speed, handgrip strength—dynamometer) Report of falls within 24 months of follow-up Minimum Data Set for Home Care (MDS-HC) | Sarcopenia: 25.4% Falls: 14.2% Cognitive Impairment: 14.2% |

| Author | Association Measurement | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Santos, 2021 [23] | OR 1.333 (0.372–4.775) | 0.658 |

| Lee et al., 2021 [24] | - | <0.001 |

| Xu et al., 2020 [25] | OR 2.00 (1.17–3.43) | - |

| Landi et al., 2012 [26] | HR 3.23(1.25–8.29) | - |

| Studies | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santos, 2021 [24] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N |

| Xu et al., 2020 [26] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Total % | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 50% | 50% | 100% | 50% |

| Studies | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al., 2021 [25] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | NP | Y |

| Landi et al., 2012 [27] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | Y | NP | Y |

| Total % | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 50% | 50% | 100% | 0% | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fhon, J.R.S.; Silva, A.R.F.; Lima, E.F.C.; Santos Neto, A.P.d.; Henao-Castaño, Á.M.; Fajardo-Ramos, E.; Püschel, V.A.A. Association between Sarcopenia, Falls, and Cognitive Impairment in Older People: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054156

Fhon JRS, Silva ARF, Lima EFC, Santos Neto APd, Henao-Castaño ÁM, Fajardo-Ramos E, Püschel VAA. Association between Sarcopenia, Falls, and Cognitive Impairment in Older People: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054156

Chicago/Turabian StyleFhon, Jack Roberto Silva, Alice Regina Felipe Silva, Eveline Fontes Costa Lima, Alexandre Pereira dos Santos Neto, Ángela Maria Henao-Castaño, Elizabeth Fajardo-Ramos, and Vilanice Alves Araújo Püschel. 2023. "Association between Sarcopenia, Falls, and Cognitive Impairment in Older People: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054156

APA StyleFhon, J. R. S., Silva, A. R. F., Lima, E. F. C., Santos Neto, A. P. d., Henao-Castaño, Á. M., Fajardo-Ramos, E., & Püschel, V. A. A. (2023). Association between Sarcopenia, Falls, and Cognitive Impairment in Older People: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054156