Asking the Experts: Using Cognitive Interview Techniques to Explore the Face Validity of the Mental Wellness Measure for Adolescents Living with HIV

Abstract

1. Introduction

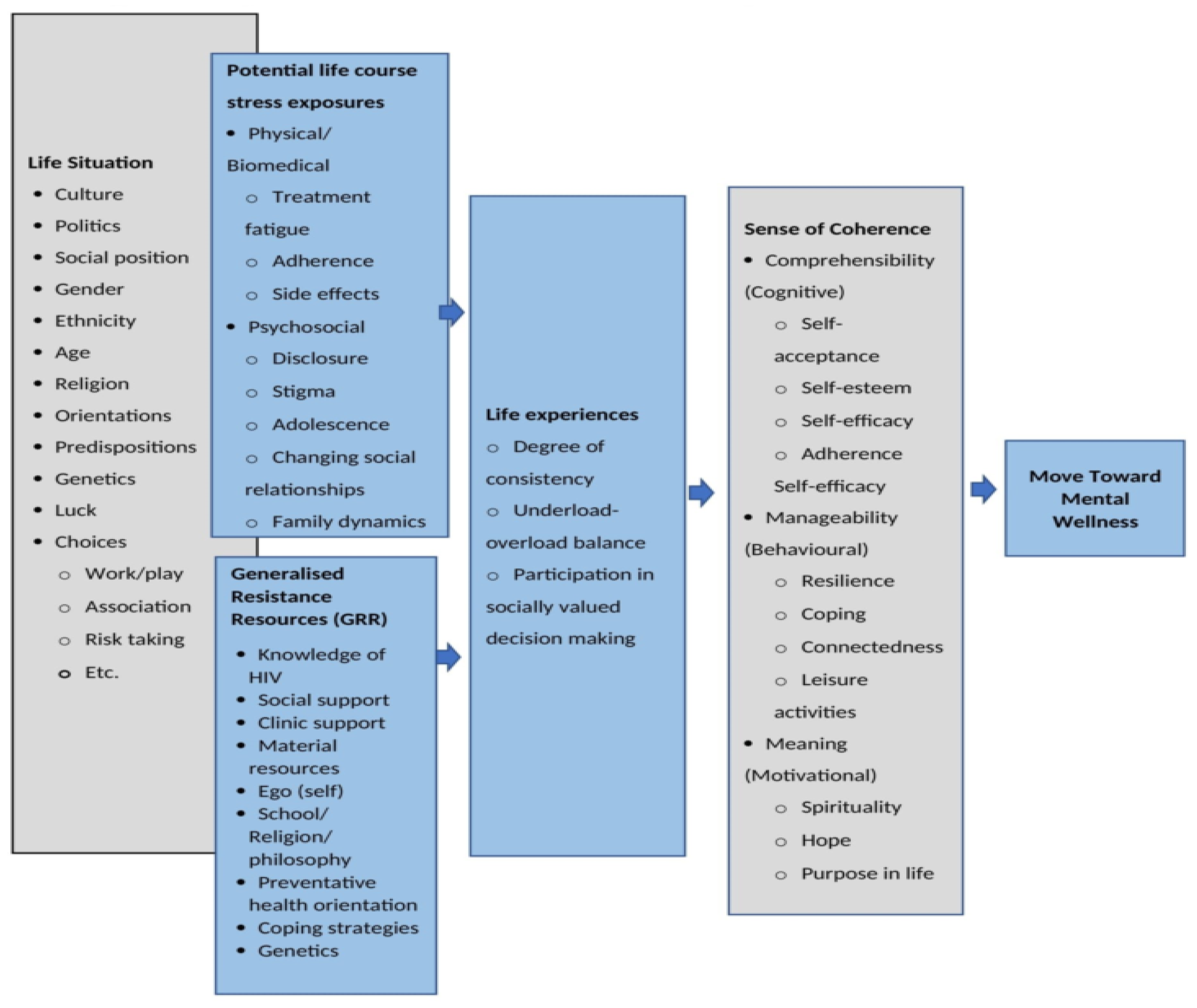

2. The Mental Wellness Measure for Adolescents Living with HIV

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. The Lexical Context in South Africa

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Ethics

4. Findings

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Study Limitations and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eriksson, C.; Arnarsson, M.; Damsgaard, M.T.; Löfstedt, P.; Potrebny, T.; Suominen, S.; Thorsteinsson, E.B.; Torsheim, T.; Välimaa, R.; Due, P. Towards enhancing research on adolescent positive mental health. Nord. Welf. Res. 2019, 4, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Youth Report: Youth and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development World. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/youth/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2018/12/WorldYouthReport-2030Agenda.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- UNICEF. Adolescents Living with HIV: Developing and Strengthening Care and Support Services. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eca/sites/unicef.org.eca/files/2017-10/Adolescents_Living_with_HIV.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Vreeman, R.C.; McCoy, B.M.; Lee, S. Mental health challenges among adolescents living with HIV. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenzi, C.; Skeen, S.; Gordon, S.; Akin-Olugbade, O.; Abrahams, N.; Bradshaw, M.; Brand, A.; Du Toit, S.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Tomlinson, M.; et al. Preventing mental health conditions in adolescents living with HIV: An urgent need for evidence. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020, 23, e25556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.; Steinmetz, A.; Paintsil, E. Impact of HIV-Status disclosure on adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-Infected children in resource-limited settings: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabri, M.; Ingabire, C.; Cohen, M.; Donenberg, G.; Nsanzimana, S. The mental health of HIV-positive adolescents. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyes, M.E.; Cluver, L.D.; Meinck, F.; Casale, M.; Newnham, E. Mental health in South African adolescents living with HIV: Correlates of internalising and externalising symptoms. AIDS Care 2019, 31, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woollett, N.; Cluver, L.; Bandeira, M.; Brahmbhatt, H. Identifying risks for mental health problems in HIV positive adolescents accessing HIV treatment in Johannesburg. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2017, 29, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.; Lovero, K.L.; Falcao, J.; Brittain, K.; Zerbe, A.; Wilson, I.B.; Kapogiannis, B.; De Gusmao, E.P.; Vitale, M.; Couto, A.; et al. Mental health and ART adherence among adolescents living with HIV in Mozambique. AIDS Care 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. Mental Health and Antiretroviral Treatment Adherence among Adolescents Living with HIV: Evidence on Risk Pathways and Protective Factors. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/esa/documents/mental-health-and-antiretroviral-treatment-adherence (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Zanoni, B.C.; Sibaya, T.; Cairns, C.; Lammert, S.; Haberer, J.E. Higher retention and viral suppression with adolescent-focused HIV clinic in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0190260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS. AIDSinfo. Available online: https://aidsinfo.unaids.org/ (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Zungu, N.; Naidoo, I.; Hodes, R.; North, A.; Mabaso, M.; Skinner, D.; Gittings, L.; Sewpaul, R.; Takatshana, S.; Jooste, S.; et al. Adolescents living with HIV in South Africa; Human Sciences Research Council: Pretoria, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mabaso, M.; Makola, L.; Naidoo, I.; Mlangeni, L.L.; Jooste, S.; Simbayi, L. HIV prevalence in South Africa through gender and racial lenses: Results from the 2012 population-based national household survey. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greifinger, R.; Dick, B. Provision of psychosocial support for young people living with HIV: Voices from the field. SAHARA-J J. Soc. Asp. HIV/AIDS 2011, 8, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavhu, W.; Berwick, J.; Chirawu, P.; Makamba, M.; Copas, A.; Dirawo, J.; Willis, N.; Araya, R.; Abas, M.A.; Corbett, E.L.; et al. Enhancing psychosocial support for HIV positive adolescents in Harare, Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonji, E.F.; Mukumbang, F.C.; Orth, Z.; Vickerman-Delport, S.A.; Van Wyk, B. Psychosocial support interventions for improved adherence and retention in ART care for adolescents and young people living with HIV: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. A Qualitative Review of Psychosocial Support Interventions for Young People Living with HIV. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70174 (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- World Health Organization. Integration of Mental Health and HIV Interventions. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240043176 (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- World Health Organization. Helping Adolescents Thrive: Guidelines on Mental Health Promotive and Preventive Interventions for Adolescents. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240011854 (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- Dambi, J.M.; Cowan, F.M.; Martin, F.; Sibanda, S.; Simms, V.; Willis, N.; Bernays, S.; Mavhu, W. Conceptualisation and psychometric evaluation of positive psychological outcome measures used in adolescents and young adults living with HIV: A mixed scoping and systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e066129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson Fadiji, A.; Wissing, M.P. Positive Psychology in Sub-Saharan Africa. In The International Handbook of Positive Psychology; Chang, E.C., Downey, C., Yang, H., Zettler, I., Muyan-Yılık, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Canfield, J.P.; Harley, D.; Hunn, V.; Haddad, K.L.; Kim, S.-H.; Elliott, W.; Mangan, L. Development and initial validation of the urban adolescent hope scale. J. Evid. Inf. Soc. Work 2018, 15, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganga, N.S.; Kutty, V.R. Measuring positive mental health: Development of the Achutha Menon Centre Positive Mental Health Scale. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2015, 27, NP1893–NP1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orth, Z.; Moosajee, F.; Van Wyk, B. Measuring mental wellness of adolescents: A systematic review of instruments. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 835601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balthip, K.; McSherry, W.; Nilmanat, K. Spirituality and dignity of Thai adolescents living with HIV. Religions 2017, 8, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, Z.; van Wyk, B. Measuring mental wellness among adolescents living with a physical chronic condition: A systematic review of the mental health and mental well-being instruments. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, T.; Joe, S.; Williams, A.; Harris, R.; Betz, G.; Stewart-Brown, S. Measuring mental wellbeing among adolescents: A systematic review of instruments. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 2349–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, N.; Hartley, S.; Bucci, S. Systematic review of self-report measures of general mental health and wellbeing in adolescent mental health. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 22, 225–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, N. A comprehensive strategy for developing closed-ended survey items for use in studies of older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2002, 57, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, M.; Pouwer, F.; Gemke, R.J.; de Waal, H.A.D.-V.; Snoek, F.J. Validation of the WHO-5 well-being index in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 2003–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Auquier, P.; Erhart, M.; Gosch, A.; Rajmil, L.; Bruil, J.; Power, M.; Duer, W.; Cloetta, B.; Czemy, L.; et al. The KIDSCREEN-27 quality of life measure for children and adolescents: Psychometric results from a cross-cultural survey in 13 European countries. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS. Ending the AIDS Epidemic for Adolescents, with Adolescents—A Practical Guide to Meaningfully Engage Adolescents in the AIDS Response. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/ending-AIDS-epidemic-adolescents_en.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- Orth, Z.; van Wyk, B. Discourses of mental wellness among adolescents living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 1435–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orth, Z.; van Wyk, B. A facility-based family support intervention to improve treatment outcomes for adolescents on antiretroviral therapy in the Cape Metropole, South Africa. J. Int. Assoc. Provid. AIDS Care 2021, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, Z.; van Wyk, B. Rethinking mental health wellness among adolescents living with HIV in the African context: An integrative review of mental wellness components. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 955869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittelmark, M.B.; Bauer, G.F.; Vaandrager, L.; Pelikan, J.M.; Sagy, S.; Eriksson, M.; Lindström, B.; Meier Magistretti, C. The Handbook of Salutogenesis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Orth, Z.; van Wyk, B. Content validation of a Mental Wellness Measuring instrument for Adolescents Living with HIV: A modified Delphi Study. 2023; Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, J.; Carlton, J.; Grundy, A.; Buck, E.T.; Keetharuth, A.D.; Ricketts, T.; Barkham, M.; Robotham, D.; Rose, D.; Brazier, J. The importance of content and face validity in instrument development: Lessons learnt from service users when developing the Recovering Quality of Life measure (ReQoL). Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1893–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVellis, R.F.; Thorpe, C.T. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 4th ed.; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Knafl, K.; Deatrick, J.; Gallo, A.; Holcombe, G.; Bakitas, M.; Dixon, J.; Grey, M. Focus on research methods the analysis and interpretation of cognitive interviews for instrument development. Res. Nurs. Health 2007, 30, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, G.B.; Artino, A.R. What do our respondents think we’re asking? Using cognitive interviewing to improve medical education surveys. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Gateway. The 11 Languages of South Africa. Available online: https://southafrica-info.com/arts-culture/11-languages-south-africa/ (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- De Klerk, S.; Jerosch-Herold, C.; Buchanan, H.; Van Niekerk, L. Cognitive Interviewing during Pretesting of the Prefinal Afrikaans for the Western Cape Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire following Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation. Occup. Ther. Int. 2020, 2020, 3749575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimbga, W.W.M.; Meier, C. The language issue in South Africa: The way forward? Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western Cape Government Education. Adapted Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement for Schools of Skills and Schools with Skills Units. 2013. Available online: https://wcedonline.westerncape.gov.za/Specialised-ed/SpecialSchools/SchoolofSkills/SoS-Curr/Curr-Maintenance.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Sherman, G.G.; Mazanderani, A.H.; Barron, P.; Bhardwaj, S.; Niit, R.; Okobi, M.; Puren, A.; Jackson, D.J.; Goga, A.E. Toward elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in South Africa: How best to monitor early infant infections within the Prevention of Mother- to-Child Transmission Program. J. Glob. Health 2017, 7, 010701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, T.M.; Thurman, T.R.; Nogela, L. “Every time that month comes, I remember”:using cognitive interviews to adapt grief measures for use with bereaved adolescents in South Africa. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2016, 28, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University of Cape Town. The Importance of the First-Ever Afrikaaps Dictionary. Available online: https://www.news.uct.ac.za/article/-2021-08-30-the-importance-of-the-first-ever-afrikaaps-dictionary (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- Dessauvagie, A.; Jörns-Presentati, A.; Napp, A.-K.; Stein, D.; Jonker, D.; Breet, E.; Charles, W.; Swart, R.L.; Lahti, M.; Suliman, S.; et al. The prevalence of mental health problems in sub-Saharan adolescents living with HIV: A systematic review. Glob. Ment. Health 2020, 7, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, S.; Rueda, H.; Lambert, M.C. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale among youth in Mexico. Int. Soc. Work 2019, 62, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, G.; Torres, M.; Pedrals, N. Validation of a Spanish Version of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form Questionnaire. Psicothema 2017, 29, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaten, C.D.; Rose, C.A.; Bonifay, W.; Ferguson, J.K. The Milwaukee Youth Belongingness Scale (MYBS): Development and validation of the scale utilizing item response theory. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 34, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Conceiving the Self; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Witten, H.; Savahl, S.; Adams, S. Adolescent flourishing: A systematic review. Cogent Psychol. 2019, 6, 1640341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V. An overview of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being concepts. In Handbook of Media Use and Well-Being; Reinecke, L., Oliver, M.B., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gentzler, A.L.; DeLong, K.L.; Palmer, C.A.; Huta, V. Hedonic and eudaimonic motives to pursue well-being in three samples of youth. Motiv. Emot. 2021, 45, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sense of Coherence | Sub-Domains (n = 11) | Number of Items (n = 113) |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensibility (Cognitive) | Self-esteem | 10 |

| Self-acceptance | 9 | |

| Self-efficacy | 9 | |

| Adherence Self-efficacy | 13 | |

| Manageability (Behavioural) | Resilience | 10 |

| Coping | 10 | |

| Connectedness | 10 | |

| Leisure activities | 10 | |

| Meaning (Motivational) | Spirituality | 7 |

| Hope | 14 | |

| Purpose in life | 11 |

| Participant (n = 9) | Age | Gender | Home Language | Education Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A01 | 19 | Female | Xhosa | School of Skills (level 4) |

| A02 | 18 | Other | Xhosa | School of Skills (level 4) |

| A03 | 18 | Female | Xhosa | Gr. 12 |

| A04 | 19 | Female | Xhosa | Gr. 12 |

| A05 | 15 | Female | Afrikaans | Gr. 8 |

| A06 | 19 | Male | Xhosa | Gr. 12 |

| A07 | 15 | Male | Xhosa | Gr. 8 |

| A08 | 17 | Female | Xhosa | Gr. 10 |

| A09 | 17 | Male | Afrikaans | Gr. 10 |

| Problem Type | Item | Domain | Explanation | Example | Proposed Revision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehension mismatch | When I fail at something important to me, I remind myself that it is part of being human. | Self-acceptance | All of the participants struggled to answer this question and would often relate it to their experience of living with HIV | A02: ‘Sometimes I will feel lonely, because I’ll be like yes, I am HIV but that does not mean that’ A03: That I’m not going to die anytime soon, ‘I’m going to live long.’ A01: ‘Strongly agree, Yeah, I think I get really disappointed.’ | Remove |

| Even when I am bad at something, I still love myself. | Self-acceptance | Some of the participants interpreted ‘bad’ as doing something bad in character rather than failing at something | A03 ‘I love myself even when I am bad?...bad things like doing bad things’ A07: ‘I don’t love myself when I do bad things’ | ‘I love myself even when I fail at something’ | |

| When something upsets me, it does not change how I feel about myself | Self-acceptance | All the participants understood the question, however one participant indicated that the wording may cause them to answer incorrectly | A04: ‘No, I strongly disagree…or is it agree?’ | ‘When something upsets me, I feel bad about myself’ | |

| I am comfortable with who I am as a person | Self-acceptance | The question intends to determine if the participant accepts themselves, but the word ‘comfortable’ can have a different interpretation | A06: ‘Being in a relaxed atmosphere or something or just being your comfort zone that could be at home or our friends’ | ‘I love myself just the way I am’ | |

| I am a valuable person, even if there are parts of myself that I do not like. | Self-acceptance | Some of the participants interpreted ‘parts’ to relate to the body rather than general aspects or characteristics | A06: ‘Body parts’ A01: ‘Like, any marks that you [gesturing to body]—like me, I have two [skin] colours… So, sometimes I look at my arms and look at my body…and I want to change it but I can’t’ | ‘I love myself, even if there are things about myself that I dislike’ | |

| I do not have much to be proud of. | Self-esteem | Some participants interpreted the question to relate to certain material possessions that they may not have | A02: ‘I don’t have much to be proud of, but I know that I can take care of my health and some things.’ A06: ‘Like asset, type of things?’ | ‘I feel like a failure’ | |

| I feel strong | Self-efficacy | Strong was interpreted differently by participants, with some relating it to physical strength | A01: ‘Because I don’t have a lot of energy as others because I have a heart problem, so I don’t have so much strength like others’ ‘Like, I mean, I feel like strong. It means that you are like you are strong. Like you have the ability to do anything.’ | ‘I have what it takes to succeed/achieve my goals’ or I have the ability to do anything I want in life’ | |

| I find ways to take my treatment every day, even when I am around people who don’t know that I am living with HIV | Adherence self-efficacy | Most participants understood the question and responded with some of the ways they would take the treatment (e.g., go to the bathroom). However, one participant believed the question asked them to take the treatment in front of others | A06: ‘I never take treatment in front of everybody.’ | ‘When I am around people who don’t know my status, I will still try to find a way to take my treatment (e.g., go to the bathroom)’ | |

| I know where to go in my community to get help | Resilience | Some participants indicated that the question may be vague. The question intends to assess whether participants know where to access resources in the community if they need them | A04: ‘Yeah, I would ask them. I don’t know. I have like, I’ve never been in the situation, like, to go and seek help from the community.’ | ‘If I had a problem, I would know where to go in my community to get help’ | |

| I do things at school that make a positive difference (i.e., make things better) | Resilience | While some participants interpreted the question correctly, such as A03, others struggled to understand and answer the question (A01) | A03: ‘Making good friends, doing different things that are good…playing sports’ A01: ‘Something that’s like different from the other things that I do’ | ‘I work well with people my age’ ’I feel good when I am school’ | |

| In general, I feel I am in control of my life | Some of the participants interpreted the question as referring to their ability to be independent rather than their ability to be in control of themselves, despite life challenges | A04: ‘I think being in control is being independent’ A08: ‘Disagree…I have to follow the rules at home’ | ‘I feel I am in control of myself’ | ||

| Question relevance | I take my treatment every day, even when my eating habits have changed. | Adherence self-efficacy | The question did not resonate with participants | A06: ‘My eating habits never change.’ A08: ‘No, I don’t know how to answer this’ | Remove |

| I take my treatment every day, even when I have problems going to the clinic. | Adherence self-efficacy | The question did not resonate with participants | A06: ‘How would you take your treatment if you couldn’t go to the clinic?’ | Remove | |

| I take my treatment every day, even when people close to me tell me not to | Adherence self-efficacy | The question did not resonate with participants | A04: ‘I never came across that’ A03: ‘No one told me’ | Remove | |

| I take my treatment every day, even when I feel like people will judge me | Adherence self-efficacy | The question did not resonate with participants | A04: ‘Strongly disagree, I have never been judged by anyone’ A01: ‘No, people think the tablets are my for my heart’ | Remove | |

| I know where to go for help when I have problems | Resilience | The wording of this question is similar to “I know where to go in my community when I need help. As such we proposed a revision. | A01: ‘I talk to my mom when I have problems’ | ‘When I have a problem, I can find what I need to solve it’ | |

| Living with HIV has strengthened my faith or spiritual beliefs | Spirituality | The participants indicated the question was not very relevant | A04: ‘No…because, like, I feel like God has a purpose. Like God created everyone. There’s a reason why I’m living with HIV’ A06: ‘No it does not apply’ | Remove | |

| Big or difficult words and sentence structure | For me, life is about learning, changing, and growing despite my circumstances | Resilience | The wording of the question made it difficult for participants to understand | A01: ‘So, yeah, there’s a lot of challenges here outside.’ A09: ‘Strongly agree… I don’t know’ | ‘I see life challenges as a chance for me to learn and grow’ |

| I think it is important to have new experiences that challenge how you think about yourself and the world | Coping | The wording of the question made it difficult for participants to understand | A06: ‘Doing things you’ve never done before?’ | Remove, similar as previous question | |

| When I have problems I think about different solutions to solve the problem | Coping | Most participants understood the question, but A01 offered a suggestion to make it easier | A01: ‘you can change it to make it easier’ | ‘When I have a problem, I think about different ways to solve the problem’ | |

| I try to avoid difficult situations as much as possible | Coping | The wording of the question made it difficult for participants to understand | A01: ‘Like, those friends, there’s always that thing that you be talking and then there will be that one person who will and report that thing and it starts to be a big thing.’ | ‘I avoid my problems’ | |

| I have friends I’m really close to and trust | Connectedness | Participants interpreted the question as having friends that they trust. Some have close friends, but they do not trust them with their status. The question was split into two to make it easier | A09: ‘Disagree, my friends don’t know’ A02: ‘I have friends, but I have not told them about my status’ | ‘I have friends I am really close to’ AND ‘I have friends that I trust’ | |

| It is important to me that I feel satisfied by the activities that I take part in. | Leisure activities | The wording of the question made it difficult for participants to understand | A07: ‘Satisfied is…I don’t know how to explain it’ A08: ‘No, sometimes I just come home from school and do homework’ | ‘I have hobbies that make me feel happy’ | |

| I will be able to provide for myself | Hope | Most participants understood the question, but A01 offered a suggestion to make it easier | A01: ‘Provide is a big English word. Maybe you can say ‘take care of myself’ | ‘I will be able to take care of myself’ | |

| I will be able to provide for my family | Hope | Similar to previous | ‘I will be able to take care of my family’ | ||

| I feel optimistic about the future | None of the participants understood the word ‘optimistic’ | A04: ‘What does that mean?’ A01: ‘That is another big word’ | ‘I feel good about my future’ | ||

| I feel a sense of purpose in my life AND I have a sense of direction in life. | Purpose in life | These two questions were seen as similar, and some participants had difficulty understanding | A06: ‘it’s the same meaning’ A03: ‘sense of direction?’ | ‘I know where I want to go in life’ | |

| I enjoy making plans for the future and working to make them come true | The question was seen as asking two different things. A04 recommended to split it into two questions | A04: ‘The question is in-between [difficult and easy to answer]’ | ‘I enjoy making plans for the future AND I work hard to achieve my goals’ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orth, Z.; Van Wyk, B. Asking the Experts: Using Cognitive Interview Techniques to Explore the Face Validity of the Mental Wellness Measure for Adolescents Living with HIV. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054061

Orth Z, Van Wyk B. Asking the Experts: Using Cognitive Interview Techniques to Explore the Face Validity of the Mental Wellness Measure for Adolescents Living with HIV. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):4061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054061

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrth, Zaida, and Brian Van Wyk. 2023. "Asking the Experts: Using Cognitive Interview Techniques to Explore the Face Validity of the Mental Wellness Measure for Adolescents Living with HIV" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 4061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054061

APA StyleOrth, Z., & Van Wyk, B. (2023). Asking the Experts: Using Cognitive Interview Techniques to Explore the Face Validity of the Mental Wellness Measure for Adolescents Living with HIV. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 4061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054061