Multicultural Identity Integration versus Compartmentalization as Predictors of Subjective Well-Being for Third Culture Kids: The Mediational Role of Self-Concept Consistency and Self-Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Third Culture Kids

1.2.2. Self-Concept and Identity Forms

1.2.3. Cultural Context and Identity

1.2.4. Self-Consistency, Self-Efficacy and TCKs

1.2.5. Multicultural Identity Configurations

1.2.6. Well-Being and TCKs’ Identity

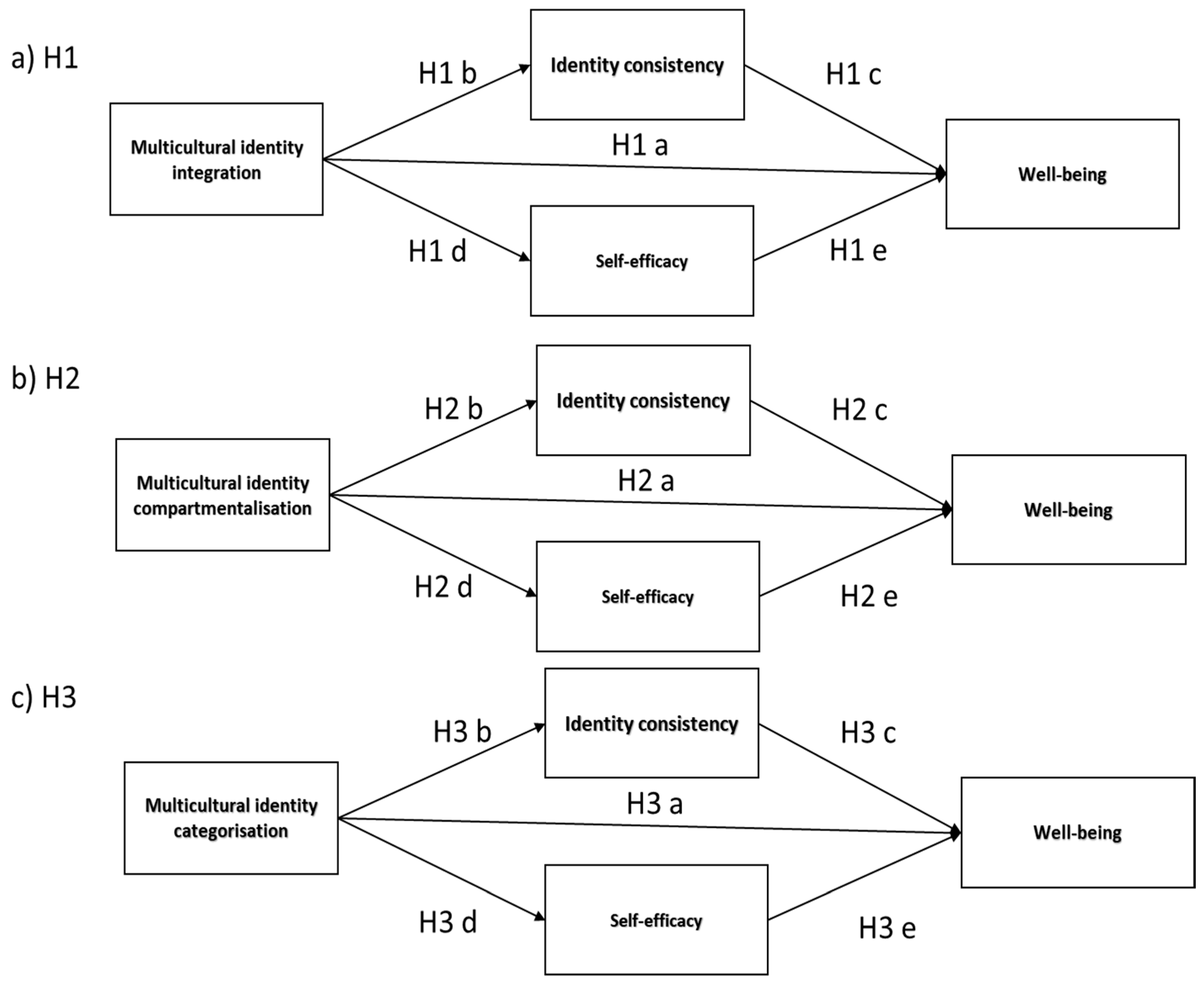

1.3. Aims and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Analytical Approach

3. Results

3.1. Correlational Analyses

3.2. Hypotheses Verification

3.2.1. Direct Effects

3.2.2. Mediation Analyses

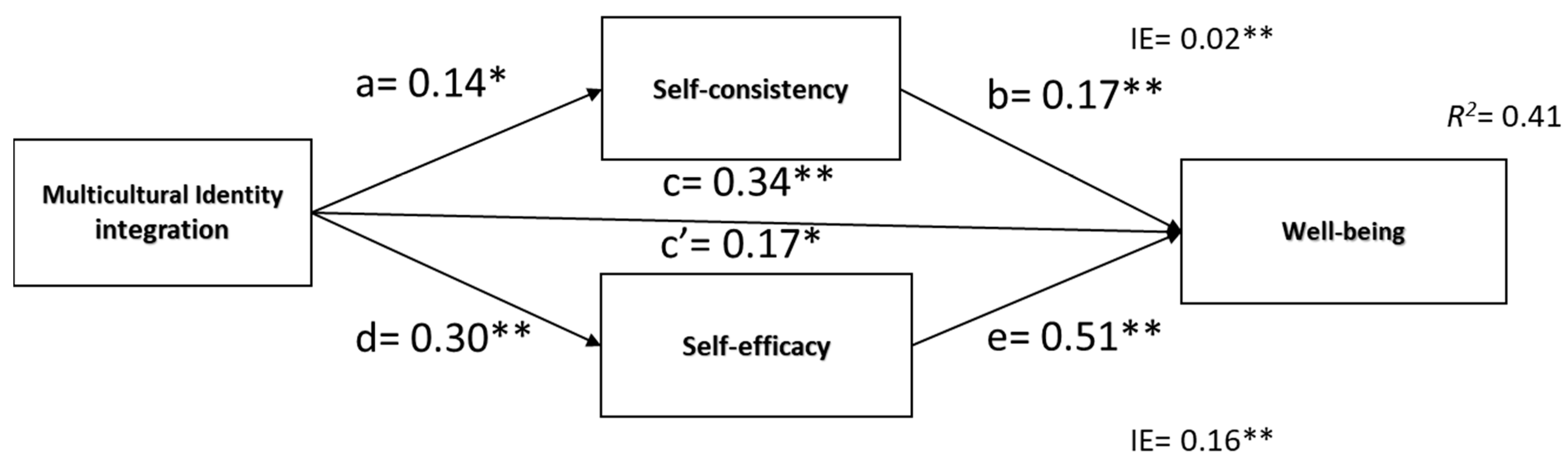

Hypothesis 1 (a, b, c, d, e)

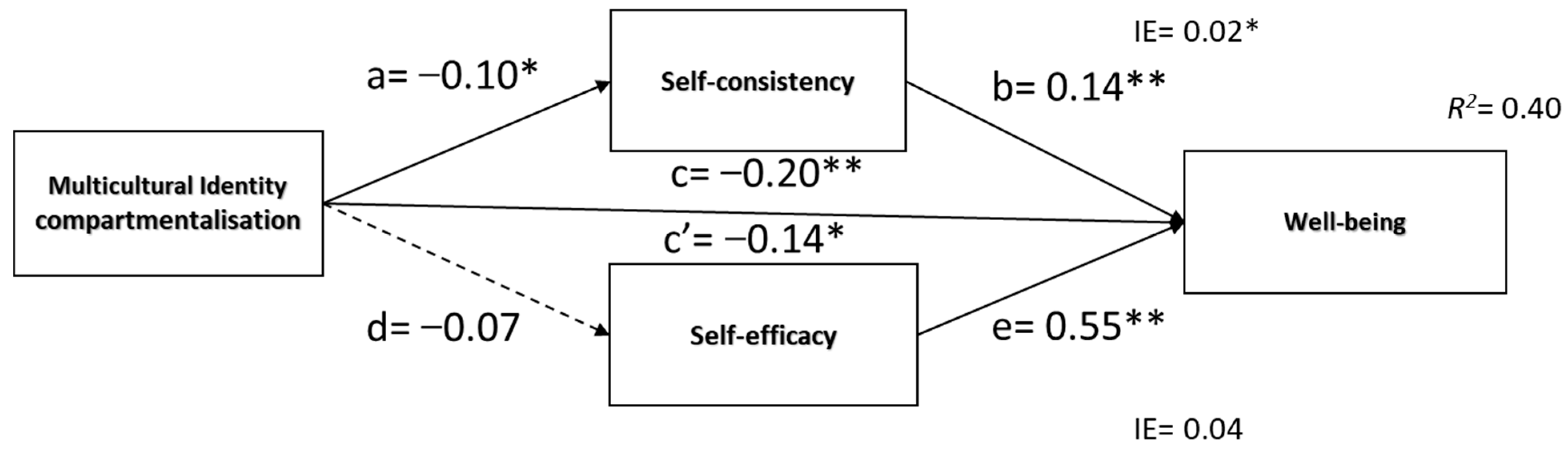

Hypothesis 2 (a, b, c, d, e)

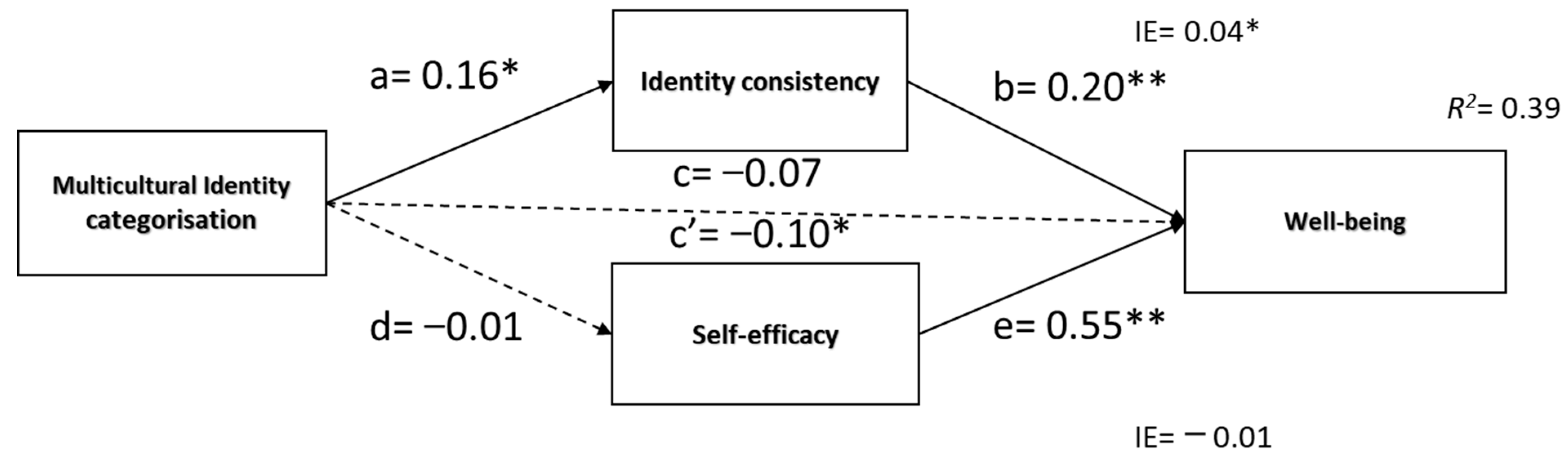

Hypothesis 3 (a, b, c, d, e)

4. Discussion

4.1. Associations between Multicultural Identity Configurations, Self-Consistency, Self-Efficacy, and Well-Being

4.2. Mediation Models Interpretation

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pollock, D.C.; Van Reken, R.E.; Pollock, M.V. Third Culture Kids. Growing Up among Worlds; Nicholas Brealey Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stokke, P. Adult Third Culture Kids: Potential Global Leaders with Global Mindset. Ph.D. Thesis, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mosanya, M.; Kwiatkowska, A. Complex but integrated: Exploring social and cultural identities of women Third Culture Kids (TCK) and factors predicting life satisfaction. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 2021, 84, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yampolsky, M.A.; Amiot, C.E.; de la Sablonnière, R. The Multicultural Identity Integration Scale (MULTIIS): Developing a comprehensive measure for configuring one’s multiple cultural identities within the self. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2016, 22, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fail, H.; Thompson, J.; Walker, G. Belonging, Identity and Third Culture Kids: Life Histories of Former International School Students. J. Res. Int. Educ. 2004, 3, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain, C. Engaged Buddhist Practice and Ecological Ethics. Worldviews Glob. Relig. Cult. Ecol. 2016, 20, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, A. Communication Strategies Contributing to the Positive Identities of Third Culture Kids: An Intercultural Communication Perspective on Identity. Ph.D. Thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hoersting, R.C.; Jenkins, S.R. No place to call home: Cultural homelessness, self-esteem and cross-cultural identities. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2011, 35, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivero, V.N.; Jenkins, S.R. Existential hazards of the multicultural individual: Defining and understanding “cultural homelessness”. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 1999, 5, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E. Identity and the Life Cycle; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Habeeb, H.; Hamid, A.A.R.M. Exploring the Relationship between Identity Orientation and Symptoms of Depression among Third Culture Kids college students. Int. J. Instr. 2021, 14, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, A.; Ali, T. Global Nomads, Cultural Chameleons, Strange Ones or Immigrants? An Exploration of Third Culture Kid Terminology with Reference to the United Arab Emirates. J. Res. Int. Educ. 2019, 18, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F. Self and Identity. An Introduction. In Advanced Social Psychology; Tesser, A., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 51–97. [Google Scholar]

- Tesser, A.; Felson, R.B.; Suls, J.M. (Eds.) Psychological Perspectives on Self and Identity; American Psychological Association (APA): Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sedikides, C.; Brewer, M.B. Individual Self, Relational Self, Collective Self; Psychology Press Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman, D. Social Idenity and Self-Regulation. In Social Psychology. Handbook of Basic Principles; Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 432–453. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, W.B., Jr.; Bosson, J.K. Self and Identity. In Handbook of Social Psychology; Fiske, S.T., Gilbert, D.T., Lindzey, G., Eds.; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 589–628. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S.T.; Taylor, S.E. Social Cognition; MacGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Harb, C.; Smith, P.B. Self-Construals across Cultures: Beyond Independence-Interdependence. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2008, 39, 178–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenens, B.; Vasteenkiste, M. When Is Identity Congruent with the Self? A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Schwartz, S.J., Luycks, K., Vignoles, V.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 381–402. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, H.R. Self-Schemata and Processing Information about the Self. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 35, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, A.P.; Sedikides, C.; Gebauer, J. Dynamics of Identity: Between Self-Enhancement and Self-Assessment. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 305–327. [Google Scholar]

- Vignoles, V.L.; Regalia, C.; Manzi, C.; Golledge, J.; Scabini, E. Beyond self-esteem: Influence of multiple motives on identity construction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 308–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breakwell, G.M. Strategies Adopted When Identity Is Threatened. Rev. Int. Psychol. Soc. 1988, 1, 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Vignoles, V.L. Identity Motives. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research; Schwartz, S.J., Luyckx, K., Vignoles, V.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 403–432. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1986; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney, J.S.; Ong, A.D. Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. J. Couns. Psychol. 2007, 54, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Chew, P.Y.-G. Cultural knowledge, category label, and social connections: Components of cultural identity in the global, multicultural context. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 16, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoles, V.L.; Owe, E.; Becker, M.; Smith, P.B.; Easterbrook, M.J.; Brown, R.; González, R.; Didier, N.; Carrasco, D.; Cadena, M.P.; et al. Beyond the “East-West” Dichotomy: Global Variation in Cultural Models of Selfhood. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2016, 145, 966–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignoles, V.L. The Motive for Distinctiveness: A Universal, but Flexible Human Need. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T.M.; Bond, M.H.; Sharkey, W.F.; Lai, C.S.Y. Unpackaging Culture’s Influence on Self-Esteem and Embarrassability: The Role of Self-Construals. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1999, 30, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, A.G.; Zane, N.W.S. Ethnic Differences in Coping with Interpersonal Stressors: A Test of Self-Construals as Cultural Mediators. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2004, 35, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S.; Park, J. Error-related brain activity reveals self-centric motivation: Culture matters. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2014, 143, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitayama, S.; Uskul, A.K. Culture, Mind, and the Brain: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2011, 62, 419–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, M.; Vignoles, V.L.; Owe, E.; Easterbrook, M.J.; Brown, R.; Smith, P.B.; Abuhamdeh, S.; Ayala, B.C.; Garðarsdóttir, R.B.; Torres, A.; et al. Being oneself through time: Bases of self-continuity across 55 cultures. Self Identity 2018, 17, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, F. When Subgroups Secede: Extending and Refining the Social Psychological Model of Schism in Groups. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 1074–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijadi, A.A. “I Am Not Weird, I Am Third Culture Kids”: Identifying Enabling Modalities for Place Identity Construction among High Mobility Populations. J. Identity Migr. Stud. 2018, 12, 2–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory. In Annals of Child Development. Vol.6. Six Theories of Child Development; Vasta, R., Ed.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1989; pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Westropp, S.; Cathro, V.; Everett, A.M. Adult third culture kids’ suitability as expatriates. Rev. Int. Bus. Strat. 2016, 26, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirttilä-Backman, A.-M.; Kassea, B.R.; Ikonen, T. Cameroonian Forms of Collectivism and Individualism. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2004, 35, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiot, C.E.; De La Sablonnière, R.; Terry, D.J.; Smith, J. Integration of Social Identities in the Self: Toward a Cognitive-Developmental Model. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 11, 364–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiot, C.E.; Doucerain, M.M.; Zhou, B.; Ryder, A. Cultural identity dynamics: Capturing changes in cultural identities over time and their intraindividual organization. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 48, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haritatos, J.; Benet-Martίnez, V. Bicultural identities: The interface of cultural, personality, and socio-cognitive processes. J. Res. Pers. 2002, 36, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhabha, H.K. The Location of Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-203-82055-1. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Weisskirch, R.S. Broadening the Study of the Self: Integrating the Study of Personal Identity and Cultural Identity. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2008, 2, 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usborne, E.; de la Sablonnière, R. Understanding My Culture Means Understanding Myself: The Function of Cultural Identity Clarity for Personal Identity Clarity and Personal Psychological Well-Being. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2014, 44, 436–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, K.; Garcia-Garzon, E.; Maguire, A.; Matz, S.; Huppert, F.A. Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: A multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F.A. Psychological Well-being: Evidence Regarding its Causes and Consequences. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2009, 1, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grob, A. Subjective Well-Being and Significant Life-Events across the Life Span. Swiss J. Psychol. 1995, 54, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Grob, A.; Wearing, A.J.; Little, T.D.; Wanner, B. Adolescents’ Well-Being and Perceived Control Across 14 Sociocultural Contexts. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F.A.; Baylis, N.; Keverne, B. (Eds.) The Science of Well-Being; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krys, K.; Park, J.; Kocimska-Zych, A.; Kosiarczyk, A.; Selim, H.A.; Wojtczuk-Turek, A.; Haas, B.W.; Uchida, Y.; Torres, C.; Capaldi, C.A.; et al. Personal Life Satisfaction as a Measure of Societal Happiness is an Individualistic Presumption: Evidence from Fifty Countries. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 2197–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usborne, E.; Taylor, D.M. The Role of Cultural Identity Clarity for Self-Concept Clarity, Self-Esteem, and Subjective Well-Being. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 36, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterbrook, M.; Vignoles, V.L. Different Groups, Different Motives: Identity Motives Underlying Changes in Identification With Novel Groups. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 1066–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittel, A.; Sisler, A. Third Culture Kids: Adjusting to a Changing World. Diskurs Kindh. Jugendforsch H 2012, 4, 487–492. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, M.B. The Social Self: On Being the Same and Different at the Same Time. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 17, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Generalised Self-Effiacy Scale. In Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs; Weinman, S., Wright, S., Johnston, M., Eds.; Nfer-Nelson: Windsor, UK, 1995; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Capri, B.; Ozkendir, O.M.; Ozkurt, B.; Karakus, F. General Self-Efficacy Beliefs, Life Satisfaction and Burnout of University Students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 47, 968–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grob, A. Berne Questionnaire of Subjective Well-Being; University of Bern: Bern, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Krys, K.; Yeung, J.C.; Capaldi, C.A.; Lun, V.M.-C.; Torres, C.; van Tilburg, W.A.P.; Bond, M.H.; Zelenski, J.M.; Haas, B.W.; Park, J.; et al. Societal emotional environments and cross-cultural differences in life satisfaction: A forty-nine country study. J. Posit. Psychol. 2022, 17, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.X.; Benet-Martínez, V.; Bond, M.H. Bicultural Identity, Bilingualism, and Psychological Adjustment in Multicultural Societies: Immigration-Based and Globalization-Based Acculturation. J. Pers. 2008, 76, 803–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downie, M.; Koestner, R.; ElGeledi, S.; Cree, K. The Impact of Cultural Internalization and Integration on Well-Being among Tricultural Individuals. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, B.; Haslam, N. Psychological Essentialism and Stereotype Endorsement. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 42, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, K.; Harji, M.B.; Angusamy, A. Determinants of Multicultural Identity for Well-Being and Performance. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 48, 488–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yampolsky, M.A.; Amiot, C.E.; de la Sablonnière, R. Multicultural identity integration and well-being: A qualitative exploration of variations in narrative coherence and multicultural identification. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, D.W.; Sue, D. Counseling the Culturally Diverse: Theory and Practice; Wiley: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, R. When Borders Overlap: Composite Identities in Children in International Schools. J. Res. Int. Educ. 2011, 10, 154–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables (n = 399) | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-consistency | 3.88 (1.25) | - | |||||

| 2. Self-efficacy | 5.00 (0.98) | 16 * | - | ||||

| 3. Integration | 4.91 (1.02) | 0.11 * | 0.31 ** | - | |||

| 4. Categorization | 4.19 (1.34) | 0.16 * | −0.07 | −0.17 ** | - | ||

| 5. Compartmentalization | 3.88 (1.09) | −0.10 * | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.48 ** | - | |

| 6. Well-being | 4.48 (0.74) | 0.23 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.22 ** | −0.07 | −0.29 ** | - |

| Predictors | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Beta | B | SE | Beta | |

| Integration | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.28 ** | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.11 * |

| Compartmentalization | −0.20 | 0.04 | −0.23 ** | −0.12 | 0.03 | −0.14 ** |

| Categorization | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.07 |

| Self-consistency | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.18 ** | |||

| Self-efficacy | 0.56 | 0.04 | 0.52 ** | |||

| R sqr (R sqr Adj) | 0.35 (0.11) | 0.65 (0.41) | ||||

| F | 18.00 (3; 395) ** | 36.98 (5; 393) ** | ||||

| Delta R sqr | 0.12 ** | 0.30 ** | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mosanya, M.; Kwiatkowska, A. Multicultural Identity Integration versus Compartmentalization as Predictors of Subjective Well-Being for Third Culture Kids: The Mediational Role of Self-Concept Consistency and Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053880

Mosanya M, Kwiatkowska A. Multicultural Identity Integration versus Compartmentalization as Predictors of Subjective Well-Being for Third Culture Kids: The Mediational Role of Self-Concept Consistency and Self-Efficacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(5):3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053880

Chicago/Turabian StyleMosanya, Magdalena, and Anna Kwiatkowska. 2023. "Multicultural Identity Integration versus Compartmentalization as Predictors of Subjective Well-Being for Third Culture Kids: The Mediational Role of Self-Concept Consistency and Self-Efficacy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 5: 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053880

APA StyleMosanya, M., & Kwiatkowska, A. (2023). Multicultural Identity Integration versus Compartmentalization as Predictors of Subjective Well-Being for Third Culture Kids: The Mediational Role of Self-Concept Consistency and Self-Efficacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053880