Formative Development of ClockWork for the Postpartum Period: A Theory-Based Intervention to Harness the Circadian Timing System to Address Cardiometabolic Health-Related Behaviors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vitaterna, M.H.; Takahashi, J.; Turek, F. Overview of circadian rhythms. Alcohol. Res. Health 2001, 25, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, S.; Prabhu, S.; Young, M. Chronobiological Influence Over Cardiovascular Function: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.J.; Christie, S.; Symonds, E.; Li, H. Circadian regulation of appetite and time restricted feeding. Physiol. Behav. 2020, 220, 112873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.E.; Murray, B.; Steiner, M. Sleep and perinatal mood disorders: A critical review. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005, 30, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ehlers, C.L.; Frank, E.; Kupfer, D. Social zeitgebers and biological rhythms. A unified approach to understanding the etiology of depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1988, 45, 948–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, S.J.; Yu, D.; Spaeth, A.; Pien, G.; Darden, N.; Riis, V.; Bersani, V.; Wallen, J.; Davey, A.; Foster, G.D. Influence of Sleep Duration on Postpartum Weight Change in Black and Hispanic Women. Obesity 2019, 27, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, S. Pregnancy: A “teachable moment” for weight control and obesity prevention. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 135.e1–135.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brawarsky, P.; Stotland, N.; Jackson, R.; Fuentes-Afflick, E.; Escobar, G.; Rubashkin, N.; Haas, J. Pre-pregnancy and pregnancy-related factors and the risk of excessive or inadequate gestational weight gain. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2005, 91, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, C.M.; Strawderman, M.S. Modifiable behavioral factors in a biopsychosocial model predict inadequate and excessive gestational weight gain. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2003, 103, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesco, K.K.; Dietz, P.M.; Rizzo, J.; Stevens, V.J.; Perrin, N.A.; Bachman, D.J.; Callaghan, W.M.; Bruce, F.C.; Hornbrook, M.C. Excessive Gestational Weight Gain and Postpartum Weight Retention Among Obese Women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 114, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, A.R.; Rössner, S.; Neovius, M.; Lourenço, P.M.; Linné, Y. Does excess pregnancy weight gain constitute a major risk for increasing long-term BMI? Obesity 2007, 15, 1278–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothberg, B.E.G.; Magriples, U.; Kershaw, T.S.; Rising, S.S.; Ickovics, J.R. Gestational weight gain and subsequent postpartum weight loss among young, low-income, ethnic minority women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 204, 52.e1–52.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.N.; Louis, J.; Saade, G.R. Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period as an Opportunity for Cardiovascular Risk Identification and Management. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, K.; Yu, K.; Han, X.; Szeto, I.M.Y.; Qin, X.; Wang, J.; Ning, Y.; Wang, P.; Ma, D. Pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain and postpartum weight retention: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2172–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuhas, M.; Moore, C.F.; Garay, J.; Brown, S.D. Improving Maternal Cardiovascular Health in Underserved Populations: A Narrative Review of Behavioral Intervention Trials Targeting Postpartum Weight Retention. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2022, 24, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linne, Y.; Barkeling, B.; Rossner, S. Long-term weight development after pregnancy. Obes. Rev. 2002, 3, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, N.M.; Nicholson, W.K.; Schmitt, J. The association of pregnancy and the development of obesity—Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis on the natural history of postpartum weight retention. Int. J. Obes. 2007, 31, 1642–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siega-Riz, A.M.; Herring, A.H.; Carrier, K.; Evenson, K.R.; Dole, N.; Deierlein, A. Sociodemographic, Perinatal, Behavioral, and Psychosocial Predictors of Weight Retention at 3 and 12 Months Postpartum. Obesity 2010, 18, 1996–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linné, Y.; Dye, L.; Barkeling, B.; Rössner, S. Long-Term Weight Development in Women: A 15-Year Follow-up of the Effects of Pregnancy. Obes. Res. 2004, 12, 1166–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, M.C.; Allen-Walker, V.; McGirr, C.; Rooney, C.; Woodside, J.V. Weight loss after pregnancy: Challenges and opportunities. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2018, 31, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, M.L.; Sawicki, M.A.; Artal, R. Structured Diet and Physical Activity Prevent Postpartum Weight Retention. J. Women’s Health 2003, 12, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leermakers, E.; Anglin, K.; Wing, R. Reducing postpartum weight retention through a correspondence intervention. Int. J. Obes. 1998, 22, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østbye, T.; Krause, K.M.; Lovelady, C.A.; Morey, M.C.; Bastian, L.A.; Peterson, B.L.; Swamy, G.K.; Brouwer, R.J.; McBride, C.M. Active Mothers Postpartum: A Randomized Controlled Weight-Loss Intervention Trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalrymple, K.V.; Flynn, A.C.; Relph, S.A.; O’Keeffe, M.; Poston, L. Lifestyle Interventions in Overweight and Obese Pregnant or Postpartum Women for Postpartum Weight Management: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery-Downs, H.E.; Insana, S.P.; Clegg-Kraynok, M.M.; Mancini, L.M. Normative longitudinal maternal sleep: The first 4 postpartum months. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 203, 465.e1–465.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stremler, R.; Hodnett, E.; Kenton, L.; Lee, K.; Weiss, S.; Weston, J.; Willan, A. Effect of behavioural-educational intervention on sleep for primiparous women and their infants in early postpartum: Multisite randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2013, 346, f1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stremler, R.; Hodnett, E.; Lee, K.; Macmillan, S.; Mill, C.; Ongcangco, L.; Willan, A. A Behavioral-Educational Intervention to Promote Maternal and Infant Sleep: A Pilot Randomized, Controlled Trial. Sleep 2006, 29, 1609–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.A.; Bates, S.; Ji, C.; Cappuccio, F.P. Systematic review and meta-analyses of the relationship between short sleep and incidence of obesity and effectiveness of sleep interventions on weight gain in preschool children. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.P.; Crowley, S.J.; Alfano, C.A.; Hannay, K.M.; Thompson, D.; Baranowski, T. Potential circadian and circannual rhythm contributions to the obesity epidemic in elementary school age children. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollmers, C.; Gill, S.; DiTacchio, L.; Pulivarthy, S.R.; Le, H.D.; Panda, S. Time of feeding and the intrinsic circadian clock drive rhythms in hepatic gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21453–21458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokkan, K.-A.; Yamazaki, S.; Tei, H.; Sakaki, Y.; Menaker, M. Entrainment of the Circadian Clock in the Liver by Feeding. Science 2001, 291, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M.; Cioffi, I.; Evangelista, A.; Ponzo, V.; Goitre, I.; Ciccone, G.; Ghigo, E.; Bo, S. Effects of time-restricted feeding on body weight and metabolism. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2020, 21, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellappa, S.L.; Qian, J.; Vujovic, N.; Morris, C.J.; Nedeltcheva, A.; Nguyen, H.; Rahman, N.; Heng, S.W.; Kelly, L.; Kerlin-Monteiro, K.; et al. Daytime eating prevents internal circadian misalignment and glucose intolerance in night work. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoogian, E.N.C.; Chow, L.S.; Taub, P.R.; Laferrère, B.; Panda, S. Time-restricted Eating for the Prevention and Management of Metabolic Diseases. Endocr. Rev. 2022, 43, 405–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buman, M.P.; Epstein, D.R.; Gutierrez, M.; Herb, C.; Hollingshead, K.; Huberty, J.L.; Hekler, E.B.; Vega-López, S.; Ohri-Vachaspati, P.; Hekler, A.C.; et al. BeWell24: Development and process evaluation of a smartphone “app” to improve sleep, sedentary, and active behaviors in US Veterans with increased metabolic risk. Transl. Behav. Med. 2016, 6, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videnovic, A.; Lazar, A.S.; Barker, R.A.; Overeem, S. ‘The clocks that time us’—Circadian rhythms in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 10, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, K.R.; Sen, A.; Hemachandran, K. A working framework for the user-centered design approach and a survey of the available methods. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2012, 2, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, U.T.; Zachary, I.; Majee, W. Employing a User-Centered Design to Engage Mothers in the Development of a mHealth Breastfeeding Application. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2019, 37, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), E.R.S. U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form. 2012. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8282/short2012.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; McKenna, K. How Many Focus Groups Are Enough? Building an Evidence Base for Nonprobability Sample Sizes. Field Methods 2016, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, C.; Howell, E.A. Perinatal Origins of Cardiovascular Health Disparities Across the Life Course. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protheroe, J.; Rogers, A.; Kennedy, A.P.; Macdonald, W.; Lee, V. Promoting patient engagement with self-management support information: A qualitative meta-synthesis of processes influencing uptake. Implement. Sci. 2008, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | n (% out of 7 Individuals) |

|---|---|

| Racial/ethnic identity (more than one could be selected) | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 2 (29%) |

| White | 6 (86%) |

| Intentionality of most recent pregnancy | |

| No | 0 (0%) |

| Yes | Yes (100%) |

| Household income | |

| $20,001–$30,000 | 2 (29%) |

| ≥$30,001 | 5 (71%) |

| Insurance status | |

| Employer-provided health insurance | 5 (71%) |

| Medicare/Medicaid health insurance | 2 (29%) |

| Food security | |

| High or marginal food security | 6 (86%) |

| Low food security | 1 (14%) |

| Relationship status | |

| Married | 6 (86%) |

| Not in a relationship | 1 (14%) |

| M ± SD | |

| Number of pregnancies | 2.9 ± 2.0 pregnancies (range: 1–7) |

| Number of births | 2.4 ± 1.5 births (range: 1–6) |

| Self-reported gestational weight gain | 27.6 ± 12.5 lbs. (range: 15–53 lbs.) |

| Years in current relationship | 4.9 ± 1.9 years married (range: 3–8 years) |

| Prompt | Examples of Responses Provided |

|---|---|

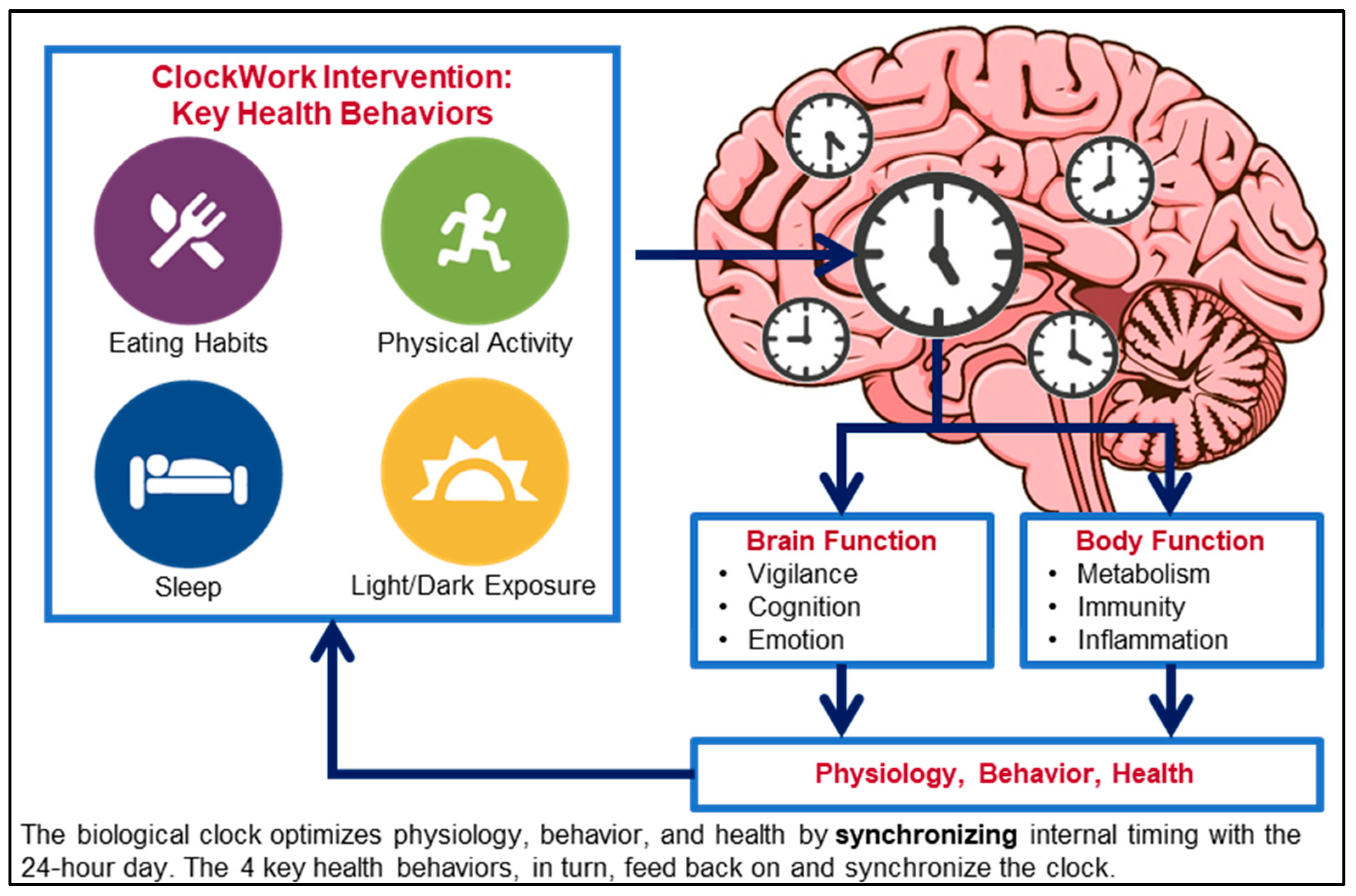

| What do you think of the ClockWork intervention model? | “The idea sounds very revolutionary. I like the inclusion of dark/light exposure. Anxiety levels, eating behavior is different between morning and night. Sleep is very interrupted postpartum and is connected to physical activity. If I sleep less, I am less likely to exercise, which leads to more anxiety about eating”. (Stakeholder interview #1) |

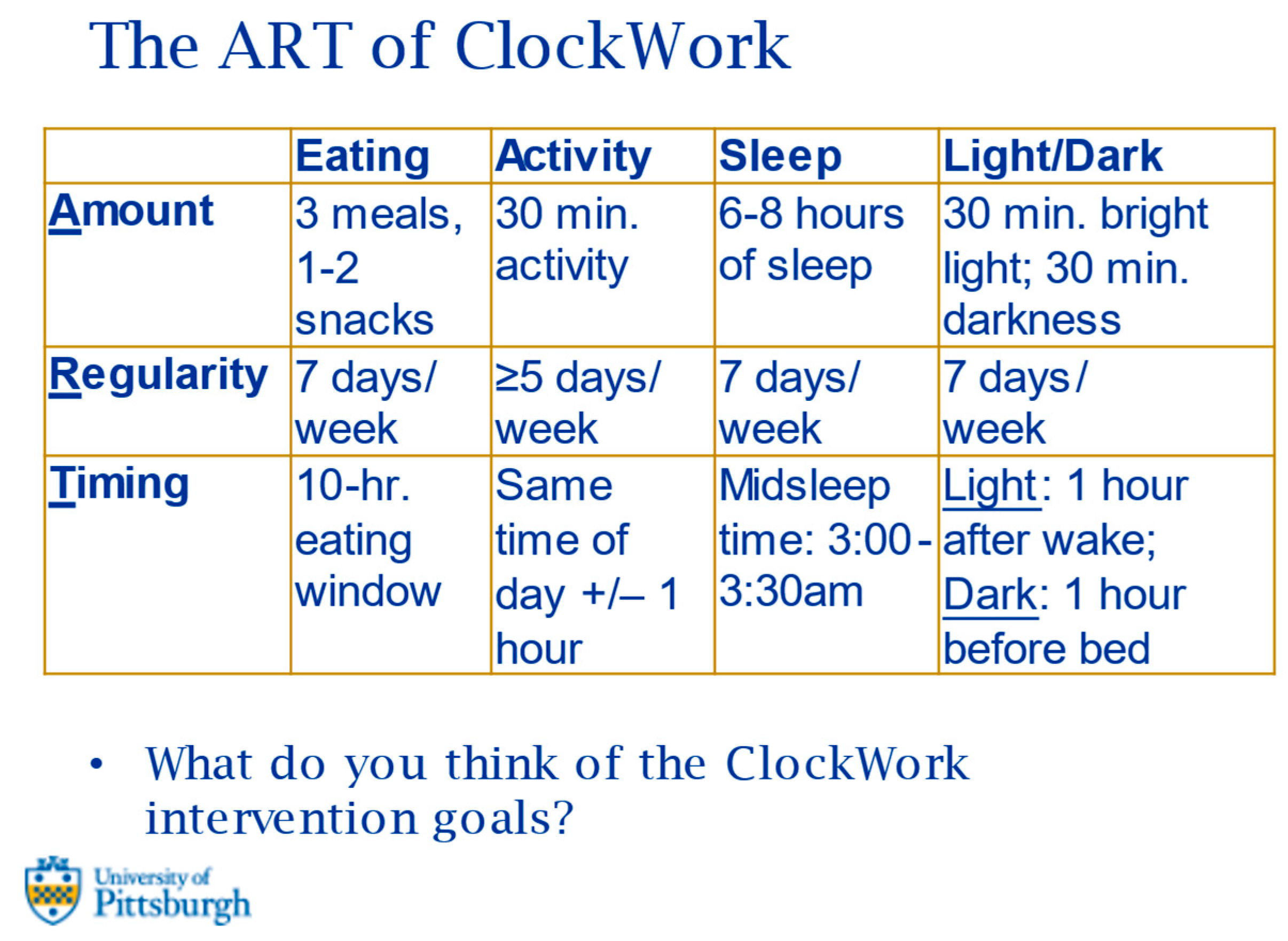

| What do you think of the ClockWork intervention goals? | General comments on the goals across behaviors: “The goals look good. Most people would be able to meet these goals”. (Stakeholder interview #5) |

| Eating goals: “These goals are doable. I would do 4 meals and 1–3 snacks. Instead of a 10-h eating window, I’d be willing to do a 12-h eating window”. (Stakeholder interview #1) “A 12 h window is better. Aside from that it’s reasonable”. (Stakeholder interview #3) | |

| Physical activity goals: “Timing may be difficult due to the baby’s schedule. Sounds reasonable. Activity will need to start 2–3 weeks postpartum”. (Stakeholder interview #3) “It would depend on when after postpartum this starts. Once cleared [for physical activity], I think it would be great”. (Stakeholder interview #4) | |

| Sleep goals: “Everything would be feasible for me. It may be difficult to put how many times I wake up during the night for the baby. It would be good to have an estimate because I may not remember”. (Stakeholder interview #1) “2–4 a.m. would be best. Seems feasible”. (Stakeholder interview #2) | |

| Light/dark exposure: “The light goal sounds good”. (Stakeholder interview #2) “Right now, I’m not good with these goals. Me and my husband watch TV before bed because that’s our time together and we sleep with the TV on. I think it’s doable. My room is rarely 100% dark. I play on my phone while I feed [the baby] to stay awake. I cannot stay awake during feedings if there’s nothing to focus on”. (Stakeholder interview #4) |

| Item | Responses n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ClockWork Intervention | The key behavior that seems most important for you to manage your weight and health postpartum | 5 (71%) Eating |

| 1 (14%) Physical activity | ||

| 1 (14%) Sleep | ||

| 0 (0%) Light/dark exposure | ||

| Willing to try eating your meals and snacks within a 10-h window (for example, between 8 a.m.–6 p.m.) | 4 (57%) No | |

| 3 (43%) Yes | ||

| Willing to try eating your meals and snacks within a 12-h window (for example, between 8 a.m.–8 p.m.) | 7 (100%) Yes | |

| 0 (0%) No | ||

| Willing to try exercising for at least 150 min/week | 7 (100%) Yes | |

| 0 (0%) No | ||

| Willing to try sleeping for 6–8 h per night | 7 (100%) Yes | |

| 0 (0%) No | ||

| Willing to try sleeping so that the midpoint of your sleep is around 3–3:30 a.m. (for example, going to bed at 11 p.m. and waking up at 7 a.m.) | 7 (100%) Yes | |

| 0 (0%) No | ||

| Willing to try getting 30 min of bright light within an hour of waking up | 7 (100%) Yes | |

| 0 (0%) No | ||

| Willing to try getting 30 min of darkness within an hour of going to bed | 6 (86%) Yes | |

| 1 (14%) No | ||

| Digital Monitoring Tools | Phone availability | 5 (71%) Yes, I have my phone with me at all times |

| 2 (29%) I have my phone with me most of the time | ||

| Access to phone for monitoring | 4 (57%) My phone is always accessible for monitoring | |

| 3 (43%) My phone is accessible sometimes and I could monitor nearly everything | ||

| Preference for monitoring nighttime events (e.g., feeding) in the moment or in the morning | 5 (71%) In the morning (remembering or recalling your awakenings, eating, caring for the baby, etc.) | |

| 2 (29%) In the moment | ||

| Anticipated barriers that would get in the way of using the app? (individuals could select all that applied) | 4 (57%) Monitoring is burdensome | |

| 4 (57%) Too busy/hard to find the time | ||

| 2 (29%) Lack of childcare | ||

| 1 (14%) Low priority/lack of motivation to manage weight |

| Eating | Activity | Sleep | Light/Dark Exposure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | 3 meals 1–2 snacks | 30 min. activity | 6–8 h of sleep | 30 min. bright light 30 min. darkness |

| Regularity | 7 days/week | ≥5 days/week | 7 days/week | 7 days/week |

| Timing | 12-h. eating window | Same time of day +/− 1 h. | Midsleep time: 2:00–4:00 a.m. | Light: 1 h. after wake Dark: 1 h. before bed |

| Intervention strategies: (1) Self-monitoring behaviors via mobile app; (2) personalized feedback; (3) tailored coaching | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Conlon, R.P.K.; Hu, H.; Saptono, A.; Hawkins, M.S.; Parmanto, B.; Levine, M.D.; Buysse, D.J. Formative Development of ClockWork for the Postpartum Period: A Theory-Based Intervention to Harness the Circadian Timing System to Address Cardiometabolic Health-Related Behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3669. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043669

Conlon RPK, Hu H, Saptono A, Hawkins MS, Parmanto B, Levine MD, Buysse DJ. Formative Development of ClockWork for the Postpartum Period: A Theory-Based Intervention to Harness the Circadian Timing System to Address Cardiometabolic Health-Related Behaviors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3669. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043669

Chicago/Turabian StyleConlon, Rachel P. Kolko, Haomin Hu, Andi Saptono, Marquis S. Hawkins, Bambang Parmanto, Michele D. Levine, and Daniel J. Buysse. 2023. "Formative Development of ClockWork for the Postpartum Period: A Theory-Based Intervention to Harness the Circadian Timing System to Address Cardiometabolic Health-Related Behaviors" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3669. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043669

APA StyleConlon, R. P. K., Hu, H., Saptono, A., Hawkins, M. S., Parmanto, B., Levine, M. D., & Buysse, D. J. (2023). Formative Development of ClockWork for the Postpartum Period: A Theory-Based Intervention to Harness the Circadian Timing System to Address Cardiometabolic Health-Related Behaviors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3669. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043669