Absenteeism at Two Occupational Health Services in Belgium from 2014 to 2021

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Intervention Program

2.2.1. Merger

2.2.2. Self-Certification

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.2. Statistical Results

3.2.1. Time Series Analysis

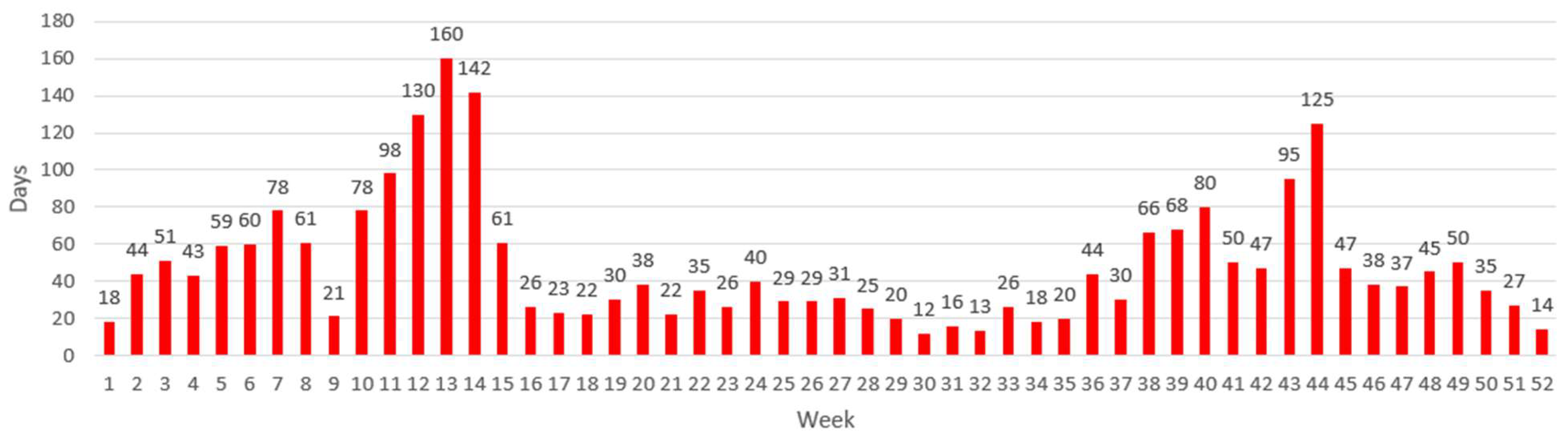

Company 1

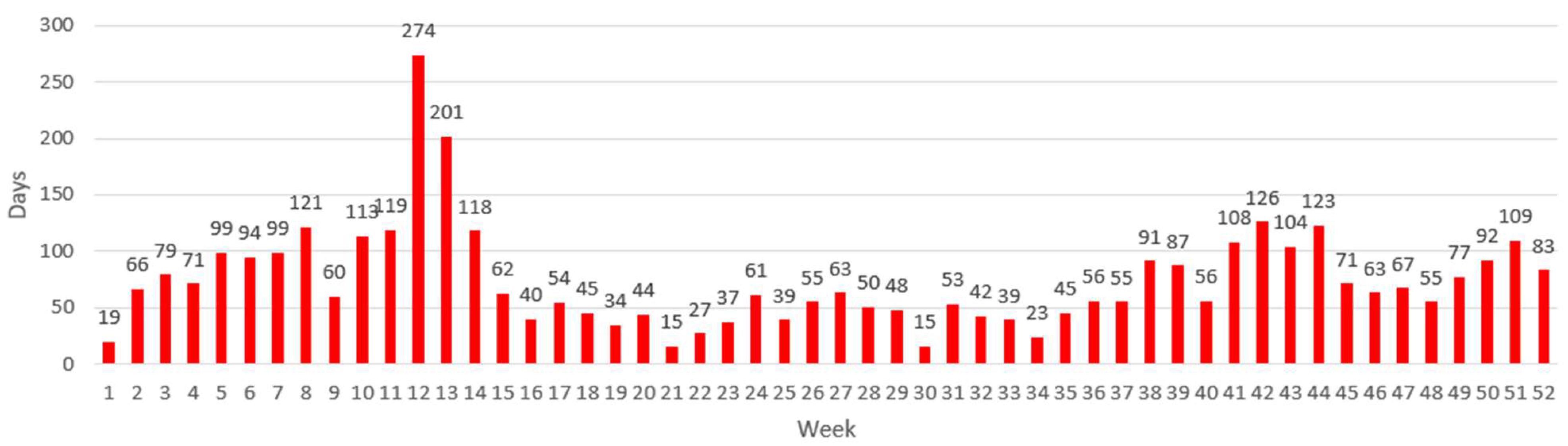

Company 2

3.2.2. Cross-Correlation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whitaker, S.C. The management of sickness absence. Occup. Environ. Med. 2001, 58, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godderis, L. Werken Is Genezen; Lannoo Campus: Leuven, Belgium, 2017; p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Verwer, I.J.G.M.; Groothof, J.W.; Gulden, J.; Gulden, J.W.J. Verschillen in verzuim en verzuimbegeleiding in Nederland en Duitsland. Tijdschr. Voor Gezondh. 2014, 92, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausto, J.; Verbeek, J.H.; Ruotsalainen, J.H.; Halonen, J.I.; Virta, L.J.; Kankaanpaa, E. Self-certification versus physician certification of sick leave for reducing sickness absence and associated costs. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 5, CD013098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstrom, V.H. Long working hours and sickness absence-a fixed effects design. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grønstad, A.; Kjekshus, L.E.; Tjerbo, T.; Bernstrøm, V.H. Work-related moderators of the relationship between organizational change and sickness absence: A longitudinal multilevel study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, M.; Valente, F.; Mak, R.; Pelfrene, E.; De Smet, P.; De Backer, G.; Kornitzer, M. Occupational stress and incidence of sick leave in the Belgian workforce: The Belstress study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Absence from Work. In: Eurofond. 2010. Available online: www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_files/docs/ewco/tn0911039s/tn0911039s.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Johnston, D.A.; Harvey, S.B.; Glozier, N.; Calvo, R.A.; Christensen, H.; Deady, M. The relationship between depression symptoms, absenteeism and presenteeism. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 256, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagerveld, S.E.; Bültmann, U.; Franche, R.L.; Van Dijk, F.J.; Vlasveld, M.C.; van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M.; Bruinvels, D.J.; Huijs, J.J.; Blonk, R.W.; Van Der Klink, J.J.; et al. Factors Associated with Work Participation and Work Functioning in Depressed Workers: A Systematic Review. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2010, 20, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, D.; Adler, D.A.; Rogers, W.H.; Lapitsky, L.; McLaughlin, T.; Reed, J. Work Performance of Employees with Depression: The Impact of Work Stressors. Am. J. Health Promot. 2010, 24, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Muntaner, C.; Kim, S.-S. Who is working while sick? Nonstandard employment and its association with absenteeism and presenteeism in South Korea. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2016, 89, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, B.; Jinnett, K. Employees’ Work Responses to Episodes of Illness Evidence From the American Time Use Survey. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 56, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grønstad, A.; Kjekshus, L.; Tjerbo, T.; Bernstrøm, V. Organizational change and the risk of sickness absence: A longitudinal multilevel analysis of organizational unit-level change in hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Väänänen, A.; Pahkin, K.; Kalimo, R.; Buunk, B.P. Maintenance of subjective health during a merger: The role of experienced change and pre-merger social support at work in white- and blue-collar workers. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 1903–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns, G. Presenteeism in the workplace: A review and research agenda. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, G.; Bodin, L.; Hagberg, J.; Aronsson, G.; Josephson, M. Sickness presenteeism today, sickness absenteeism tomorrow? A prospective study on sickness presenteeism and future sickness absenteeism. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009, 51, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prater, T.; Smith, K. Underlying Factors Contributing To Presenteeism And Absenteeism. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2011, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markussen, S.; Røed, K.; Røgeberg, O.J.; Gaure, S. The anatomy of absenteeism. Journal of health economics. 2011, 30, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, K.; Buzzanell, P. Blue-Collar Work, Career, and Success: Occupational Narratives of Sisui. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2004, 32, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocakulah, M.C.; Kelley, A.G.; Mitchell, K.M.; Ruggieri, M.P. Absenteeism Problems And Costs: Causes, Effects And Cures. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2016, 15, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Habaibeh, A.; Watkins, M.; Waried, K.; Javareshk, M.B. Challenges and opportunities of remotely working from home during Covid-19 pandemic. Global Transitions. 2021, 3, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weekly Absences From Work, by Sex and Age—Weekly Data. Eurostat. 2015–2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat (accessed on 29 July 2022).

| KERRYPNX | Company 1 | Company 2 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 n = 1147 | 2019 n = 923 | 2021 n = 835 | 2014 n = 1087 | 2019 n = 1626 | 2021 n = 1811 | |||||||

| Total sick days (number of days) | 2850 | 2374 | 2256 | 2483 | 3576 | 4377 | ||||||

| FTE | 413.09 | 441.47 | 441.47 | 645.75 | 781.9 | 828.35 | ||||||

| Total sick days per FTE (%) | 6.90 | 5.38 | 5.11 | 3.85 | 4.57 | 5.28 | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Gender of absentees | ||||||||||||

| Men | 153 | 13.34 | 147 | 15.93 | 127 | 15.21 | 272 | 25.02 | 413 | 25.40 | 477 | 26.34 |

| Women | 994 | 86.66 | 776 | 84.07 | 708 | 84.79 | 815 | 74.98 | 1213 | 74.60 | 1334 | 73.66 |

| Age of absentees (years) | ||||||||||||

| <25 | 20 | 1.74 | 10 | 1.08 | 20 | 2.40 | 39 | 3.59 | 18 | 1.11 | 46 | 2.54 |

| 25–34 | 186 | 16.22 | 240 | 26.00 | 218 | 26.11 | 303 | 27.87 | 517 | 31.80 | 474 | 26.17 |

| 35–44 | 465 | 40.54 | 222 | 24.05 | 226 | 27.07 | 395 | 36.33 | 512 | 31.49 | 594 | 32.80 |

| 45–54 | 323 | 28.16 | 266 | 28.82 | 197 | 23.59 | 220 | 20.24 | 368 | 22.63 | 462 | 25.51 |

| 55–64 | 148 | 12.90 | 182 | 19.72 | 165 | 19.76 | 124 | 11.41 | 194 | 11.93 | 233 | 12.87 |

| ≥65 | 5 | 0.44 | 3 | 0.33 | 9 | 1.08 | 6 | 0.55 | 17 | 1.05 | 2 | 0.11 |

| Function of absentees | ||||||||||||

| Administration | 532 | 46.38 | 442 | 47.89 | 279 | 33.41 | 276 | 25.39 | 412 | 25.33 | 415 | 22.92 |

| Medical prevention | 387 | 33.74 | 320 | 34.67 | 356 | 42.63 | 539 | 49.59 | 778 | 47.85 | 925 | 51.08 |

| Non-medical prevention | 177 | 15.43 | 109 | 11.81 | 140 | 16.77 | 272 | 25.02 | 436 | 26.81 | 470 | 25.95 |

| Management | 51 | 4.45 | 45 | 4.88 | 49 | 5.87 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.06 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0.76 | 11 | 1.32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Region of absentees | ||||||||||||

| Antwerp | 25 | 2.18 | 39 | 4.23 | 28 | 3.35 | 280 | 25.76 | 575 | 35.36 | 572 | 31.58 |

| Brussels | 367 | 32.00 | 296 | 32.07 | 326 | 39.04 | 70 | 6.44 | 191 | 11.75 | 239 | 13.20 |

| Limburg | 9 | 0.78 | 9 | 0.98 | 16 | 1.92 | 101 | 9.29 | 126 | 7.75 | 194 | 10.71 |

| East Flanders | 33 | 2.88 | 65 | 7.04 | 58 | 6.95 | 131 | 12.05 | 193 | 11.87 | 221 | 12.20 |

| West Flanders | 7 | 0.61 | 13 | 1.41 | 12 | 1.44 | 77 | 7.08 | 161 | 9.9 | 145 | 8.01 |

| Flemish Brabant | 14 | 1.22 | 13 | 1.41 | 1 | 0.12 | 196 | 18.03 | 320 | 19.68 | 334 | 18.44 |

| Luxembourg | 31 | 2.7 | 1 | 0.11 | 10 | 1.20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Liège | 425 | 37.05 | 217 | 23.51 | 192 | 22.99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hainaut | 184 | 16.04 | 228 | 24.70 | 150 | 17.97 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Namur | 52 | 4.53 | 42 | 4.55 | 41 | 4.91 | 31 | 2.85 | 57 | 3.51 | 99 | 5.47 |

| Walloon Brabant | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.12 | 201 | 18.49 | 3 | 0.18 | 7 | 0.39 |

| Lag | Cross | Std. Error * |

|---|---|---|

| −7 | −0.035 | 0.056 |

| −6 | −0.017 | 0.056 |

| −5 | −0.056 | 0.056 |

| −4 | −0.016 | 0.056 |

| −3 | −0.090 | 0.056 |

| −2 | −0.231 | 0.056 |

| −1 | −0.348 | 0.056 |

| 0 | −0.428 | 0.056 |

| 1 | −0.261 | 0.056 |

| 2 | −0.203 | 0.056 |

| 3 | −0.032 | 0.056 |

| 4 | −0.046 | 0.056 |

| 5 | −0.034 | 0.056 |

| 6 | −0.039 | 0.056 |

| 7 | −0.027 | 0.056 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moerland, I.; Vervaet, N.; Godderis, L.; Versée, M.; Du Bois, M. Absenteeism at Two Occupational Health Services in Belgium from 2014 to 2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043660

Moerland I, Vervaet N, Godderis L, Versée M, Du Bois M. Absenteeism at Two Occupational Health Services in Belgium from 2014 to 2021. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043660

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoerland, Ilse, Nouchka Vervaet, Lode Godderis, Mathieu Versée, and Marc Du Bois. 2023. "Absenteeism at Two Occupational Health Services in Belgium from 2014 to 2021" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043660

APA StyleMoerland, I., Vervaet, N., Godderis, L., Versée, M., & Du Bois, M. (2023). Absenteeism at Two Occupational Health Services in Belgium from 2014 to 2021. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043660