Reforms in China’s Vaccine Administration—From the Perspective of New Governance Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Legal Interpretation of Vaccine Incidents and Revelation of Potential Conflicts

2.1. The Crisis Simmered in Planned Mode of Vaccine Circulation: Vaccine Incident in Suqian City and Healthcare Reform

2.1.1. Load Shedding: The Radical Marketization in Healthcare Reform

2.1.2. The End of State’s Monopoly of Non-Immunity-Planning Vaccines

2.2. Vaccine Incidents Alternately Occurred in the Process of Production and Circulation

2.2.1. The Faulty Vaccine Incident of Yanshen Biological Technology Stock Company in 2010

2.2.2. The Shandong Illegal Vaccine Sales Incident in 2016

2.3. General Outbreak: The Changsheng Vaccine Incident in 2018

3. Integrated System of Vaccine Administration

3.1. The Evolution of Vaccine Circulation: From Unified Mode to Public Resources Trading Mode

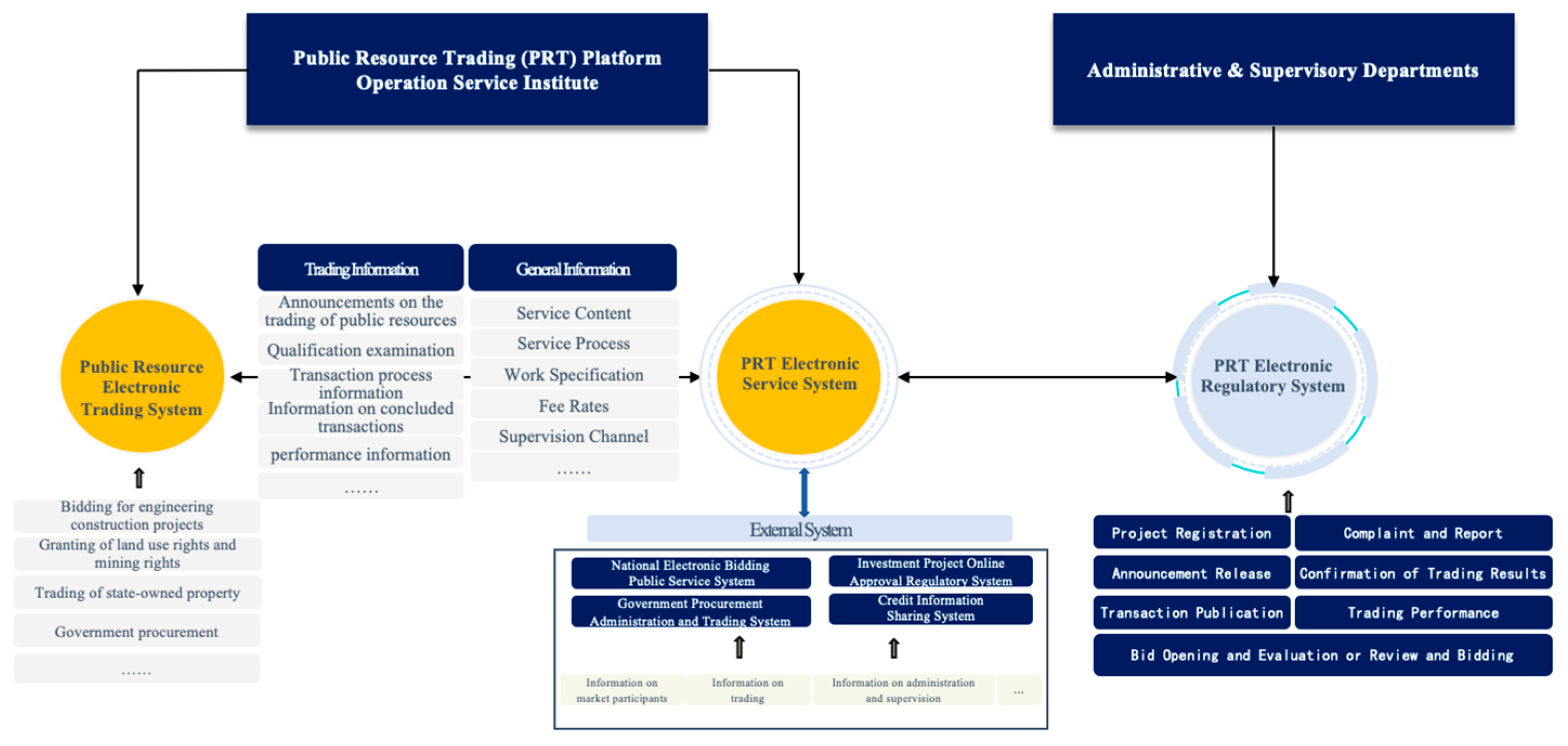

3.1.1. The Architecture of the Public Resource Trading Platform System

3.1.2. The Vaccine Circulation under Public Resource Trading Platform

3.2. The Development of Vaccine Lot Release

4. New Governance in Vaccine Administration

4.1. Decentralized or Not: That Is a Question for Vaccine Administration

4.2. Structurally Integrated Decentralization

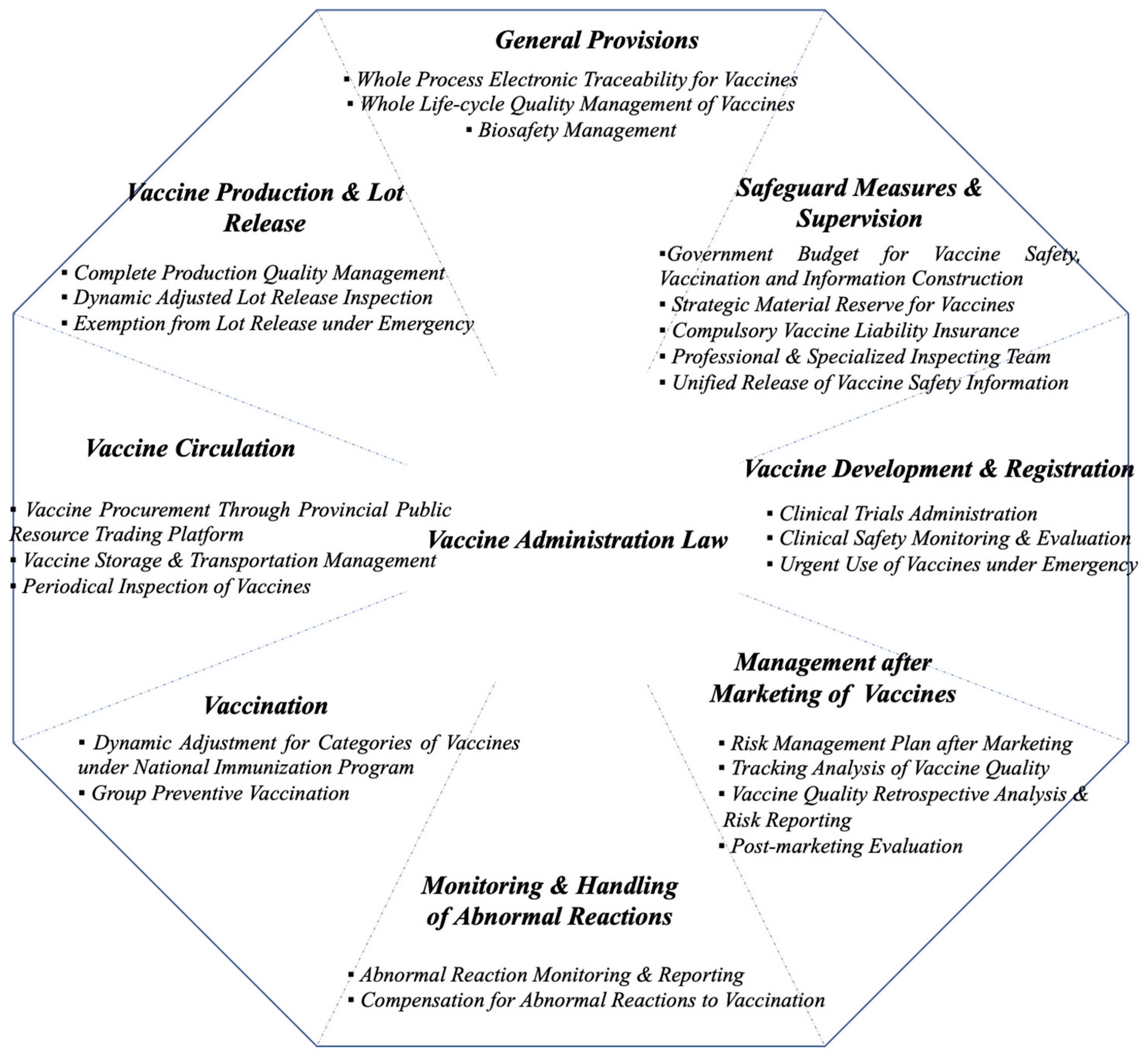

5. The Anatomy of Vaccine Administration Law in China

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, W.; Liu, D.; Zheng, J.; Liu, Y.; An, Z.; Rodewald, L.; Zhang, G.; Su, Q.; Li, K.; Xu, D.; et al. Loss of confidence in vaccines following media reports of infant deaths after hepatitis B vaccination in China. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Hu, H.; Zhou, S.; Liu, Q. Vaccine scandal and crisis in public confidence in China. Lancet 2016, 387, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Penders, B.; Horstman, K. Addressing vaccine hesitancy in China: A scoping review of Chinese scholarship. Vaccines 2019, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, J. Balancing state supervision and market: Challenge and countermeasures of vaccine safety. Chin. Adm. Manag. 2018, 10, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chen, B. Reflection and Restatement of the Second Kind of Vaccine Supervision Mechanism from the Perspective of Constitutionalism. Med. J. China 2011, 24, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, J.M. Law and governance in the 21st century regulatory state. Tex. Law Rev. 2007, 86, 819. [Google Scholar]

- Lobel, O. The Renew Deal: The Fall of Regulation and the Rise of Governance in Contemporary Leal Thought. Minn. Law Rev. 2004, 89, 342. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X. Piqianfaliang Chixu Zengjia Yimiao Hangye Gao Jingqidu Liao Yanxu [Vaccine Industry’s High Prosperity Expected to Continue as Lot Release Volume Continues to Increase]. China Securities Daily. 21 January 2021. Available online: https://finance.china.com.cn/industry/medicine/20210121/5481467.shtml (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Zou, L.P.; Yang, G.; Ding, Y.X.; Wang, H.Y. Two decades of battle against polio: Opening a window to examine public health in China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 14, e9–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China News Network. Zhongguo Yi Wei Yiqianyuwan Ertong Jiezhong Yigan Yimiao Shou Biaozhang [China Honored for Having Vaccinated More than 10 Million Children against Hepatitis B]. Sohu Net. 26 July 2006. Available online: https://health.sohu.com/20060726/n244451000.shtml (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.chinacdc.cn/ztxm/jksn/snzj/201202/t20120207_57053.html (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Jiangsu suqian Jiayimiao Fengbo: Wenti Chu Zai Liutong Jingxiao Huanjie? [Jiangsu Suqian Fake Vaccine Controversy: The Problem in the Circulation of Vaccine]. Sohu Net. 23 August 2004. Available online: https://news.sohu.com/20040823/n221672536.shtml (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Huang, Y. Governing Health in Contemporary China; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. Research Report on Medical Reform in Suqian. China Health 2007, 1, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wuhan Shengwu Zhipin Yanjiusuo [Wuhan Institute of Biological Products]. Wikipedia. 17 June 2021. Available online: https://zh.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%E6%AD%A6%E6%B1%89%E7%94%9F%E7%89%A9%E5%88%B6%E5%93%81%E7%A0%94%E7%A9%B6%E6%89%80&oldid=72572414 (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- The State Council of P.R.C. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2005-05/23/content_275.htm (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Li, S. Shi “Piqianfa” Zhidu Buling Haishi Ling You Yinqing [Is the “Approval” System Does Not Work or Another Hidden Agenda]. China Youth Daily. 5 April 2010. In March 2013, the State Food and Drug Administration Was Rebranded and Restructured as the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA), Elevating it to a Ministerial-Level Agency. In 2018, as Part of China’s 2018 Government Administration Overhaul, the Name Was Changed to National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) and Merged into the Newly Created State Administration for Market Regulation. Available online: https://zqb.cyol.com/content/2010-04/05/content_3167311.htm (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- National Medical Products Administration. Available online: https://www.nmpa.gov.cn/xxgk/fgwj/bmgzh/20201221174641125.html?type=pc&m= (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Chen, X. “Shan Dong Yi Miao An” Liang Nian: 91 Fen Pan jue 137 Ren Huo Xing, 64 Ren You Gong Zhi [Two Years of “Shandong Vaccine Case”: 91 Judgments, 137 People Sentenced to Imprisonment, 64 People with Public Office]. The Paper. 28 March 2018. Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_2045189 (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Chongqingshi Yiquanmian Tingyong Changchun Changsheng Kuangquanyimiao [Chongqing has Completely Stopped Using Changchun Changsheng Rabies Vaccine]. Xinhua Net. 18 July 2018. Available online: https://m.xinhuanet.com/cq/2018-07/18/c_1123143899.htm (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Hendriksen, C.; Arciniega, J.L.; Bruckner, L.; Chevalier, M.; Coppens, E.; Descamps, J.; Duchêne, M.; Dusek, D.M.; Halder, M.; Kreeftenberg, H.; et al. The consistency approach for the quality control of vaccines. Biologicals 2008, 36, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimiao Shijian Guo Qu Xuduo Tian Dan Zhexie Yituan Ni Xuyao Liaojie [Many Days Have Passed since the Vaccine Incident, but These Are the Questions You Need to Know]. China News. 3 August 2018. Available online: https://www.chinanews.com/gn/2018/08-03/8588248.shtml (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Wang, C. Analysis on unity of legislation of Public Resource Trade in China. J. Chin. Acad. Gov. 2017, 3, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Interim Measures for the Administration of Public Resources Trading Platforms. Available online: http://www.chinatax.gov.cn/chinatax/n810341/n810765/n1990035/201606/c2304070/5118371/files/40d618f83f494486b2586d0405deb7cd.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Yingdui Erlei Yimiao Xinzheng Gengzu, Sichuansheng Butie Shixian Jikong Lenglian Huanjie Yimiao Duanque [Sichuan Province Subsidizes County CDC Cold Chains to Ease Vaccine Shortages in Response to New Obstruction of Class II Vaccines]. The Paper. 8 August 2017. Available online: http://m.thepaper.cn/wifiKey_detail.jsp?contid=1754967&from=wifiKey# (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Qin, M. Baibaipo Mianfei Yimiao Que Huo Chouhuai Hefei Jiazhang! Weihe Zheme Nanda? [Hefei Parents Are Worried about the Shortage of Free Vaccine! Why is it so Hard to Get Vaccinated?]. Online Hefei. 14 June 2017. Available online: https://www.ahwang.cn/p/1645086.html (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- The Economic Observer. Yimiao Youxiaoxing Choujian Bili Bushi 5% Quanguo Yimiao Qiye Mianlin Feijian [Vaccine Effectiveness Sampling Ratio Not 5%, National Vaccine Companies Face Unannounced tests]. Sohu Net. 25 July 2018. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/243195502_118622 (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Independent Lot Release of Vaccines by Regulatory Authorities; WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lobel, O. New Governance as Regulatory Governance. In The Oxford Handbook of Governance; Levi-Four, D., Ed.; University of San Diego: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Willke, H. Three types of legal structure: The conditional, the purposive and the relational program. In Dilemmas of the Law in the Welfare State; European University Institute: Fiesole, Italy, 1986; pp. 180–299. [Google Scholar]

- Teubner, G. Concepts, Aspects, Limits, Solutions. Juridification of Social Spheres: A Comparative Analysis in the Areas ob Labor, Corporate, Antitrust and Social Welfare Law; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2012; Volume 6, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, R.B. Reconstitutive law. Md. Law. Rev. 1986, 46, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Janicke, M.; Helmut, W. Summary: Global environmental policy learning. National environmental policies: A comparative study of capacity-building. In National Environmental Policies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 299–313. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, L. The End of the New Deal and the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Iowa Law Rev. 1996, 82, 1269. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.; David, M. Trubek. Mind the gap: Law and new approaches to governance in the European Union. Eur. Law J. 2002, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262, 311; Supreme Court: Washington, DC, USA, 1932.

- Handler, J. Down from Bureaucracy: The Ambiguity of Privatization and Empowerment; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Starr, P. The meaning of privatization. Yale Law Policy Rev. 1998, 6, 6–41. [Google Scholar]

- Vischer, R.K. Subsidiarity as a principle of governance: Beyond devolution. Ind. Law Rev. 2001, 35, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, W. The Community Economic Development Movement: Law, Business, and the New Social Policy; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2002; pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- O’Higgins, M. Social Welfare and Privatization: The British Experience. In Privatization and the Welfare State; Kamerman, S.B., Kahn, A.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989; pp. 157–177. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, A. The Political Economy of Privatization. In Privatization and the Welfare State; LeGrand, J., Robinson, R., Eds.; George Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest, Australia, 1984; pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Handler, J. Postmodernism, protest, and the new social movements. Law Soc. Rev. 1992, 26, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judt, T. Reappraisals: Reflections on the Forgotten Twentieth Century; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sabel, C.; William, H.S. Destabilization rights: How public law litigation succeeds. Harv. Law Rev. 2003, 117, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teubner, G. Substantive and reflexive elements in modern law. Law Soc. Rev. 1982, 17, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonet, P.; Selznick, P. Law and Society in Transition: Toward Responsive Law; Taylor & Francis: Milton Park, UK, 2007; pp. 73–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Commerce People Republic of China. Cong “Jianguanma” Dao “Zhuisuma”, Yaopin Xinxihua Zhuisu Tixi Jianshe Jiasu Tuijin [From “Regulatory Code” to “Traceability Code”, the Construction of Drug Information Technology Traceability System to Accelerate]. National Important Product Traceability System. 23 October 2018. Available online: https://zycpzs.mofcom.gov.cn/html/yaopin/2018/10/1540261029456.html (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Vaccine Administration Law of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.lawinfochina.com/display.aspx?id=30707&lib=law (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- World Health Organization, China National Regulatory Authority (NRA) for Vaccines Receives WHO Endorsement, World Health Organization. 14 July 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/china/news/detail/04-07-2014-china-national-regulatory-authority-(nra)-for-vaccines-receives-who-endorsement (accessed on 10 June 2022).

| Time | Location | Vaccine Incident Type |

|---|---|---|

| June 2004 | Suqian city, Jiangsu Province | Circulation |

| June 2005 | Si county, Anhui Province | Circulation |

| 2007–2010 | Shanxi Province | Circulation |

| February 2009 | Dalian City, Liaoning Province | Production & Lot Release |

| December 2009 | Jiangsu Province | Production & Lot Release |

| September 2012 | Weifang city, Shandong Province | Circulation |

| March 2016 | Shandong Province | Circulation |

| July 2018 | Jilin Province | Production & Lot Release |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, L.; Zhang, L. Reforms in China’s Vaccine Administration—From the Perspective of New Governance Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043450

Tang L, Zhang L. Reforms in China’s Vaccine Administration—From the Perspective of New Governance Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043450

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Lin, and Lingling Zhang. 2023. "Reforms in China’s Vaccine Administration—From the Perspective of New Governance Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043450

APA StyleTang, L., & Zhang, L. (2023). Reforms in China’s Vaccine Administration—From the Perspective of New Governance Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043450