Risk Perception of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: Influencing Factors and Implications for Environmental Health Crises

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

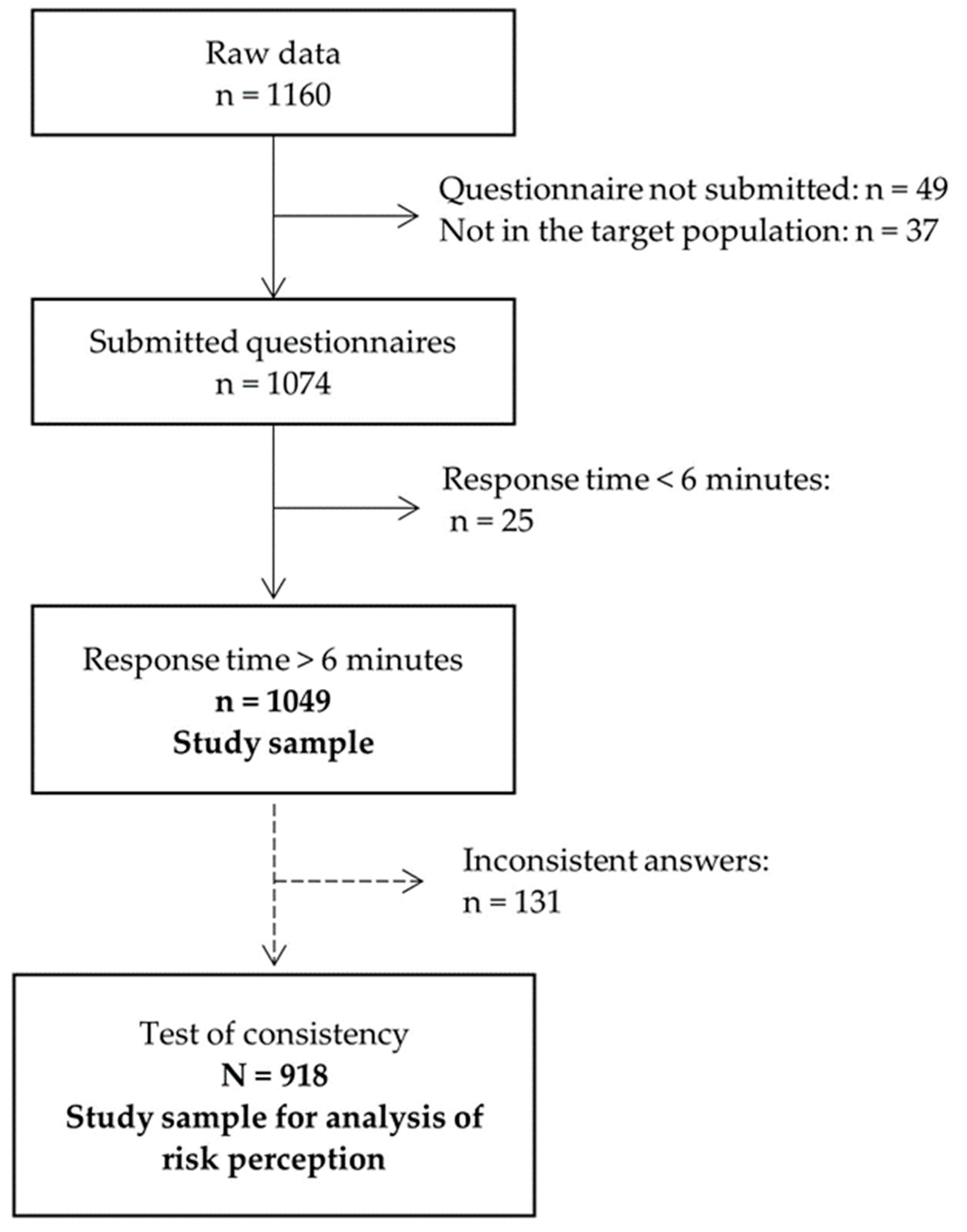

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics and COVID-19 Risk Factors

2.3.2. Health and Economic Impact

2.3.3. Risk Perception

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Health and Economic Impact by the Pandemic

3.2.1. Health Impact

3.2.2. Economic Impact

3.3. Associations between Health/Economic Impact and Risk Perception of SARS-CoV-2

3.4. SARS-CoV-2 Risk Perception and Climate Change Risk Perception

4. Discussion

4.1. Risk Perception of SARS-CoV-2 and the Influence of Health and Economic Impacts

4.2. Risk Perception in Contemporaneous Environmental Health Crises

4.3. Implications for Risk Communication in Environmental Health Crises

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Slovic, P. The Perception of Risk, Reprinted; Earthscan Publ.: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 9781853835285. [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist, M.; Sütterlin, B. Human and nature-caused hazards: The affect heuristic causes biased decisions. Risk Anal. 2014, 34, 1482–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, R.S.; Zwickle, A.; Walpole, H. Developing a Broadly Applicable Measure of Risk Perception. Risk Anal. 2019, 39, 777–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cori, L.; Bianchi, F.; Cadum, E.; Anthonj, C. Risk Perception and COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryhurst, S.; Schneider, C.R.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; van der Bles, A.M.; Spiegelhalter, D.; van der Linden, S. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UBA. Monitoringbericht 2019 zur Deutschen Anpassungsstrategie an den Klimawandel: Bericht der Interministeriellen Arbeitsgruppe Anpassungsstrategie der Bundesregierung, Dessau-Roßlau. 2019. Available online: www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/monitoringbericht-2019 (accessed on 2 December 2022).

- Swim, J.; Clayton, S.; Doherty, T.; Gifford, R.; Howard, G.; Reser, J.; Stern, P.; Weber, E. Psychology and Global Climate Change: Addressing a Multi-Faceted Phenomenon and Set of Challenges; A report by the American Psychological Association’s task force on the interface between psychology and global climate change; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- van Bavel, J.J.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N.; et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kerkhove, M.D.; Ryan, M.J.; Ghebreyesus, T.A. Preparing for “Disease X”. Science 2021, 374, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- de Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Environmental Psychology: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Incorporated: Newark, NJ, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-119-24108-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzoni, I.; Nicholson-Cole, S.; Whitmarsh, L. Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Glob. Environ. Change 2007, 17, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, A.; Fischer, H.; Amelung, D.; Litvine, D.; Aall, C.; Andersson, C.; Baltruszewicz, M.; Barbier, C.; Bruyère, S.; Bénévise, F.; et al. Household preferences for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in four European high-income countries: Does health information matter? A mixed-methods study protocol. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lujala, P.; Lein, H.; Rød, J.K. Climate change, natural hazards, and risk perception: The role of proximity and personal experience. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botzen, W.; Duijndam, S.; van Beukering, P. Lessons for climate policy from behavioral biases towards COVID-19 and climate change risks. World Dev. 2021, 137, 105214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, J.-O.; Abson, D.J.; von Wehrden, H. The coronavirus pandemic as an analogy for future sustainability challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 317–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenert, D.; Funke, F.; Mattauch, L.; O’Callaghan, B. Five Lessons from COVID-19 for Advancing Climate Change Mitigation. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 76, 751–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohommad, A.; Pugacheva, E. Impact of COVID-19 on Attitudes to Climate Change and Support for Climate Policies. IMF Work. Pap. 2022, 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanedo, R.D.; Manning, P. COVID-19: Lessons for the climate change emergency. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakučionytė-Skodienė, M.; Liobikienė, G. Climate change concern, personal responsibility and actions related to climate change mitigation in EU countries: Cross-cultural analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T.; Verschoor, M.; Albers, C.J.; Böhm, G.; Fisher, S.D.; Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Steg, L. When worry about climate change leads to climate action: How values, worry and personal responsibility relate to various climate actions. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 62, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, H.-J.; Hove, T. Risk Perceptions and Risk Characteristics. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.E.; Patel, N.G.; Levy, M.A.; Storeygard, A.; Balk, D.; Gittleman, J.L.; Daszak, P. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 2008, 451, 990–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morens, D.M.; Daszak, P.; Markel, H.; Taubenberger, J.K. Pandemic COVID-19 Joins History’s Pandemic Legion. mBio 2020, 11, e00812-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SINUS-Institute. Sinus-Milieus–Der Goldstandard der Zielgruppensegmentation: b4p 2019 III mit Sinus-Milieus--Strukturanalyse. Available online: https://www.sinus-institut.de/sinus-milieus (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Huang, J.L.; Curran, P.G.; Keeney, J.; Poposki, E.M.; DeShon, R.P. Detecting and Deterring Insufficient Effort Responding to Surveys. J. Bus. Psychol. 2012, 27, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RKI. SARS-CoV-2 Steckbrief zur Coronavirus-Krankheit-2019 (COVID-19): Stand 26.11.2021. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Steckbrief.html (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Hövermann, A. Soziale Lebenslagen, soziale Ungleichheit und Corona-Auswirkungen für Erwerbstätige: Eine Auswertung der HBS-Erwerbstätigenbefragung im April 2020; Policy Brief WSI No. 44; Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaftliches Institut (WSI): Düsseldorf, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:101:1-2020071011444104053350 (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Frondel, M.; Kussel, G.; Larysch, T.; Osberghaus, D. [RWI] Klimapolitik während der Corona-Pandemie: Ergebnisse Einer Haushaltserhebung; RWI-Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung e.V: Essen, Germany, 2020; ISBN 978-3-86788-997-1. [Google Scholar]

- Walpole, H.D.; Wilson, R.S. Extending a broadly applicable measure of risk perception: The case for susceptibility. J. Risk Res. 2021, 24, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. JOSS 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelle, W. Psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research, R package version 2.2.3; R Core Team: Evanston, IL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hetkamp, M.; Schweda, A.; Bäuerle, A.; Weismüller, B.; Kohler, H.; Musche, V.; Dörrie, N.; Schöbel, C.; Teufel, M.; Skoda, E.-M. Sleep disturbances, fear, and generalized anxiety during the COVID-19 shut down phase in Germany: Relation to infection rates, deaths, and German stock index DAX. Sleep Med. 2020, 75, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, C.R.; Dryhurst, S.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; Spiegelhalter, D.; van der Linden, S. COVID-19 risk perception: A longitudinal analysis of its predictors and associations with health protective behaviours in the United Kingdom. J. Risk Res. 2021, 24, 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, C.F.; Bélanger, J.J.; Faller, D.G.; Buttrick, N.R.; Mierau, J.O.; Austin, M.M.K.; Schumpe, B.M.; Sasin, E.M.; Agostini, M.; Gützkow, B.; et al. Lives versus Livelihoods? Perceived economic risk has a stronger association with support for COVID-19 preventive measures than perceived health risk. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Harris, P.R.; Epton, T. Does heightening risk appraisals change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 511–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kecinski, M.; Messer, K.D.; McFadden, B.R.; Malone, T. Environmental and Regulatory Concerns During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from the Pandemic Food and Stigma Survey. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 76, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostrom, A.; Böhm, G.; Hayes, A.L.; O’Connor, R.E. Credible Threat: Perceptions of Pandemic Coronavirus, Climate Change and the Morality and Management of Global Risks. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 578562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candini, V.; Brescianini, S.; Chiarotti, F.; Zarbo, C.; Zamparini, M.; Caserotti, M.; Gavaruzzi, T.; Girardi, P.; Lotto, L.; Tasso, A.; et al. Conspiracy mentality and health-related behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multiwave survey in Italy. Public Health 2022, 214, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, K.; Larsen, S.; Øgaard, T. How to define and measure risk perceptions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capstick, S.; Whitmarsh, L.; Nash, N.; Haggar, P.; Lord, J. Compensatory and Catalyzing Beliefs: Their Relationship to Pro-environmental Behavior and Behavioral Spillover in Seven Countries. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P.; Galizzi, M.M. Like ripples on a pond: Behavioral spillovers and their implications for research and policy. J. Econ. Psychol. 2015, 47, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostrom, A.; Hayes, A.L.; Crosman, K.M. Efficacy, Action, and Support for Reducing Climate Change Risks. Risk Anal. 2019, 39, 805–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elledge, B.L.; Brand, M.; Regens, J.L.; Boatright, D.T. Implications of public understanding of avian influenza for fostering effective risk communication. Health Promot. Pract. 2008, 9, 54S–59S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, P.D.; Belton, C.A.; Lavin, C.; McGowan, F.P.; Timmons, S.; Robertson, D.A. Using Behavioral Science to help fight the Coronavirus. JBPA 2020, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Item |

|---|---|

| Affect |

|

| Probability |

|

| Consequences |

|

| n | % | % NRW Distribution * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1048 | ||

| Female | 524 | 50.0 | 51 |

| Male | 523 | 49.9 | 49 |

| Diverse | 1 ** | 0.1 | |

| Age (in years) | 1048 | ||

| 16–29 | 209 | 19.9 | 21 |

| 30–39 | 142 | 13.6 | 14 |

| 40–49 | 169 | 16.1 | 16 |

| 50–59 | 212 | 20.2 | 19 |

| 60–69 | 167 | 15.9 | 15 |

| ≥70 | 149 | 14.2 | 15 |

| Net household income | 996 | ||

| <EUR 1000 | 72 | 7.2 | 7 |

| EUR 1000–2000 | 233 | 23.4 | 24 |

| EUR 2001–3000 | 248 | 24.9 | 27 |

| EUR 3001–4000 | 207 | 20.8 | 20 |

| ≥EUR 4001 | 236 | 23.7 | 22 |

| Size of residence (inhabitants) | 1037 | ||

| <100.000 | 283 | 27.3 | 27 |

| 100,000–499,999 | 350 | 33.8 | 33 |

| ≥500,000 | 404 | 39.0 | 40 |

| Pandemic Impact | Dimensions of Risk Perception | N | B | CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health (yes/no) | Affect | 899 | 0.11 | −0.01–0.24 | 0.083 |

| Probability | 898 | 0.29 | 0.16–0.42 | <0.001 | |

| Consequences | 897 | 0.05 | −0.09–0.19 | 0.454 | |

| Economic (low/high) | Affect | 896 | 0.45 | 0.32–0.57 | <0.001 |

| Probability | 895 | 0.26 | 0.14–0.39 | <0.001 | |

| Consequences | 894 | 0.12 | −0.02–0.26 | 0.087 |

| Pandemic Mean (SD) | n 1 | Climate Change Mean (SD) | n 1 | p 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affect | 3.42 (0.96) | 916 | 3.31 (0.98) | 918 | <0.05 |

| Probability | 2.46 (0.97) | 915 | 3.31 (0.93) | 910 | <0.001 |

| Consequences | 3.47 (1.07) | 914 | 3.30 (0.98) | 917 | <0.001 |

| Dimensions of SARS-CoV-2 Risk Perception 1 | Dimensions of Climate Change Risk Perception 2 | N | B | CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affect | Affect | 895 | 0.33 | 0.26–0.41 | <0.001 |

| Probability | −0.02 | −0.08–0.05 | 0.592 | ||

| Consequences | 0.00 | −0.07–0.07 | 0.992 | ||

| Affect | Probability | 887 | 0.21 | 0.13–0.28 | <0.001 |

| Probability | 0.07 | 0.01–0.13 | 0.031 | ||

| Consequences | 0.04 | −0.03–0.10 | 0.301 | ||

| Affect | Consequences | 894 | 0.20 | 0.12–0.27 | <0.001 |

| Probability | 0.05 | −0.01–0.12 | 0.087 | ||

| Consequences | 0.20 | 0.13–0.26 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mc Call, T.; Lopez Lumbi, S.; Rinderhagen, M.; Heming, M.; Hornberg, C.; Liebig-Gonglach, M. Risk Perception of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: Influencing Factors and Implications for Environmental Health Crises. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043363

Mc Call T, Lopez Lumbi S, Rinderhagen M, Heming M, Hornberg C, Liebig-Gonglach M. Risk Perception of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: Influencing Factors and Implications for Environmental Health Crises. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043363

Chicago/Turabian StyleMc Call, Timothy, Susanne Lopez Lumbi, Michel Rinderhagen, Meike Heming, Claudia Hornberg, and Michaela Liebig-Gonglach. 2023. "Risk Perception of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: Influencing Factors and Implications for Environmental Health Crises" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043363

APA StyleMc Call, T., Lopez Lumbi, S., Rinderhagen, M., Heming, M., Hornberg, C., & Liebig-Gonglach, M. (2023). Risk Perception of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: Influencing Factors and Implications for Environmental Health Crises. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043363