Leisure Programmes in Hospitalised People: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Criteria

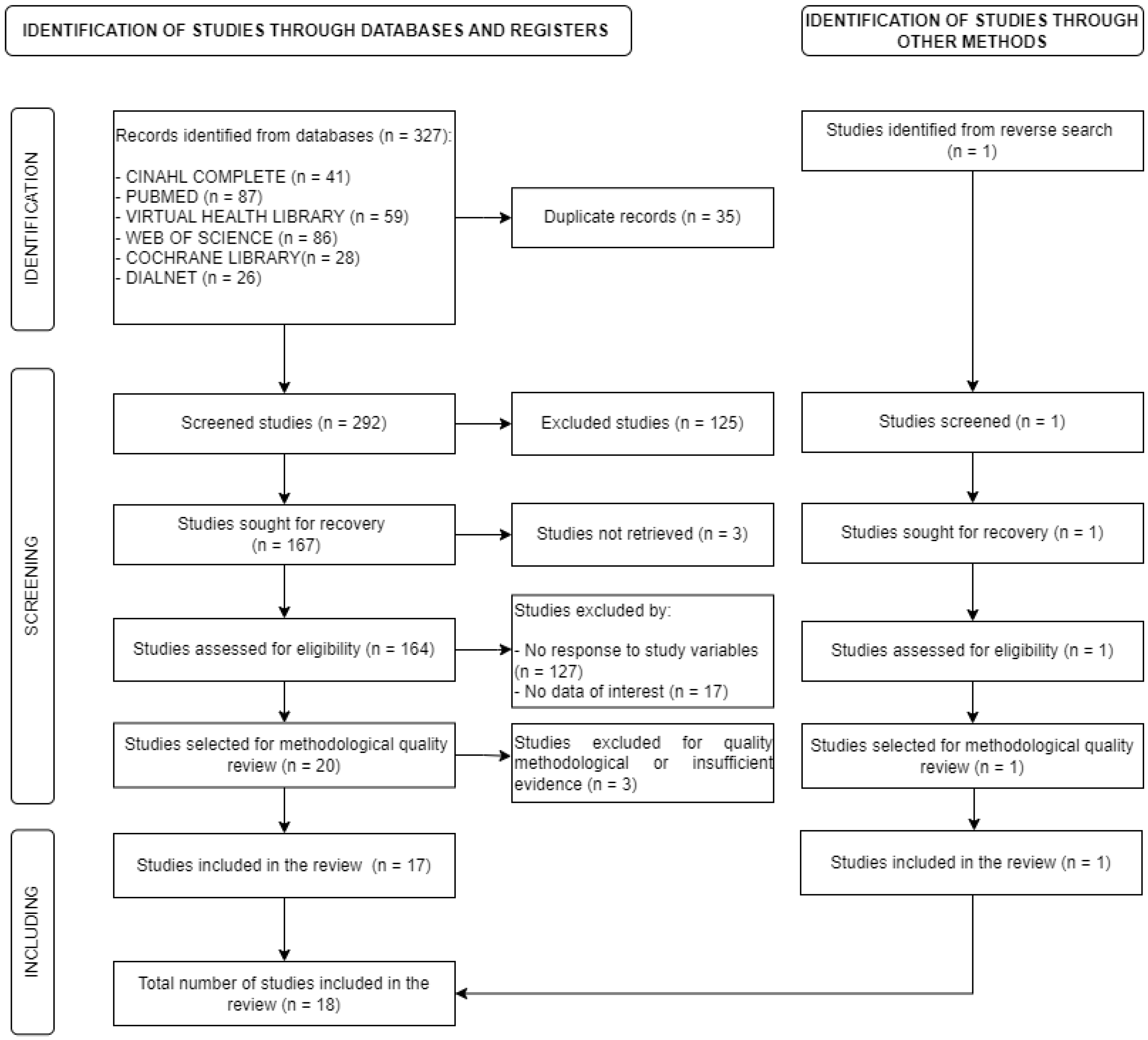

2.4. The Study Selection Process

2.5. Research Variables

2.6. Methodological Quality, Level of Evidence and Grade of Recommendation

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Quality

3.2. Hospital Leisure Programmes

3.3. Effectiveness of the Leisure Activities Included in the Programmes

3.4. Strengths and Weaknesses Reported by Health Professionals about Hospital Leisure Programmes

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Review

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| DATABASE | SEARCH STRINGS |

|---|---|

| CINAHL COMPLETE | (leisure activities OR animation OR play therapy OR clown OR bibliotherapy OR art therapy OR music therapy) AND (hospitals) |

| (animation OR entertainment OR laughter therapy) AND (hospitals) | |

| PUBMED | ((((((leisure activities [Title/Abstract]) OR (play therapy [Title/Abstract])) OR (clown [Title/Abstract])) OR (bibliotherapy [Title/Abstract])) OR (art therapy [Title/Abstract])) OR (music therapy [Title/Abstract])) AND (hospitals [Title/Abstract]) |

| (((lively [Title/Abstract]) OR (entertainment [Title/Abstract])) OR (laughter therapy [Title/Abstract])) AND (hospitals [Title/Abstract]) | |

| VIRTUAL HEALTH LIBRARY | (leisure activities) OR (play therapy) OR (clown) OR (bibliotherapy) OR (art therapy) OR (music therapy) AND (hospitals) |

| (lively) OR (entertainment) OR (laughter therapy) AND (hospitals) | |

| WEB OF SCIENCE | (leisure activities) OR (play therapy) OR (clown) OR (bibliotherapy) OR (art therapy) OR (music therapy) AND (hospitals) |

| (lively) OR (entertainment) OR (laughter therapy) AND (hospitals) | |

| COCHRANE LIBRARY | leisure activities OR play therapy OR clown OR bibliotherapy OR art therapy OR music therapy AND hospitals |

| lively OR entertainment OR laughter therapy AND hospitals | |

| DIALNET | leisure activities OR play therapy OR clown OR bibliotherapy OR art therapy OR music therapy AND hospitals |

| lively OR entertainment OR laughter therapy AND hospitals |

References

- Clarke, C.; Stack, C.; Martin, M. Lack of meaningful activity on acute physical hospital wards: Older people’s experiences. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 81, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Gutiérrez, K.; Cardona Lozada, T.A.; Ortiz Escobar, C.P. Jugar para sanar: La mediación de los padres a partir del juego y del juguete en el proceso de hospitalización del niño en el Hospital Infantil Santa Ana. In Dinámicas Actuales de Investigación. Los Jóvenes Buscan y Descubren/Corporación Universitaria Lasallista; Lasallista: Caldas, Colombia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooyen, D.; Janine, P. Foundations of Nursing Practice: Fundamentals of Holistic Care; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua, J.V. Convalescent Companions: Hospital Entertainment before Television". Prescription TV: Therapeutic Discourse in the Hospital and at Home; Duke University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, V. Principios Fundamentales De Los Cuidados De Enfermeria. Available online: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/14985/v44n3p217.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Bermúdez Rey, M.T. Animación sociocultural en el Hospital Materno Infantil de Oviedo: La experiencia del voluntariado de Cruz Roja. Pulso Revista de Educación 2011, 34, 89–99. Available online: https://doaj.org/article/986002adc6a64304ac1f9bd7ae692295 (accessed on 24 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- PRE-MAX Consortium; European Comission Patients’ Rights in the European Union-Mapping eXercise. Final Report. 2016. Available online: http://www.activecitizenship.net/multimedia/import/files/patients_rights/charter-of-rights/publications-of-the-charter/Patients_Rights_in_the_European_Union.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Leenen, H.J.J. Development of Patients’ Rights and Instruments for the Promotion of Patients’ Rights. Eur. J. Health Law 1996, 3, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Nurses Association (ANA) Center of Ethics and Human Rights. The Nurse’s Role in Ethics and Human Rights: Protecting and Promoting Individual Worth, Dignity, and Human Rights in Practice Settings. Available online: https://www.nursingworld.org/~4af078/globalassets/docs/ana/ethics/ethics-and-human-rights-protecting-and-promoting-final-formatted-20161130.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- American Hospital Association. The Patient Care Partnership. Understanding Expectations, Rights and Responsabilities. J. Eng. 2018. Available online: https://www.aha.org/other-resources/patient-care-partnership (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Chan, Z.C.; Wu, C.M.; Yip, C.H.; Yau, K.K. Getting through the day: Exploring patients’ leisure experiences in a private hospital. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 3257–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaspyros, S.; Uppal, S.; Khan, S.A.; Paul, S.; O’Regan, D.J. Analysis of bedside entertainment services’ effect on post cardiac surgery physical activity: A prospective, randomised clinical trial. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2008, 34, 1022–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, C.H.; Douglas, M.R. Patient-friendly hospital environments: Exploring the patients’ perspective. Health Expect 2004, 7, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, C.H.; Douglas, M.R. Patient-centred improvements in health-care built environments: Perspectives and design indicators. Health Expect 2005, 8, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelander, T.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Children’s best and worst experiences during hospitalisation. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2010, 24, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Mckenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). JBI Man. Evid. Synth. 2020. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 28 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. Chichester, UK, 2011. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)-NCBI. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/ (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Health Sciences Descriptors. Available online: https://decs.bvsalud.org/I/homepagei.htm (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Instrumentos Para la Lectura Crítica | CASPe. Available online: https://redcaspe.org/materiales/ (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. Declaración de la Iniciativa STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology): Directrices para la comunicación de estudios observacionales. Gac. Sanit 2008, 22, 144–150. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0213-91112008000200011 (accessed on 7 April 2021). [CrossRef]

- Manterola, C.; Asenjo-Lobos, C.; Otzen, T. Jerarquización de la evidencia: Niveles de evidencia y grados de recomendación de uso actual. Rev. Chil. De Infectología 2014, 31, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallek, R.; Corey, K.; Qamar, A.; Vernisie, S.N.; Hoberman, A.; Selwyn, P.A.; Fausto, J.A.; Marcus, P.; Kvetan, V.; Lounsbury, D.W. Soothing the heart with music: A feasibility study of a bedside music therapy intervention for critically ill patients in an urban hospital setting. Palliat. Support. Care 2020, 18, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheufler, A.; Wallace, D.P.; Fox, E. Comparing Three Music Therapy Interventions for Anxiety and Relaxation in Youth With Amplified Pain. J. Music. Ther. 2020, 58, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, K.; Tesch, L.; Dawborn, J.; Courtney-Pratt, H. Art, music, story: The evaluation of a person-centred arts in health programme in an acute care older persons’ unit. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2018, 13, e12186. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/opn.12186 (accessed on 17 April 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shella, T.A. Art therapy improves mood, and reduces pain and anxiety when offered at bedside during acute hospital treatment. Arts Psychother. 2018, 57, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Park, K.M.; Park, H. Effects of Laughter Therapy on Depression and Sleep among Patients at Long-term Care Hospitals. Sŏngin Kanho Hakhoe Chi 2017, 29, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, K.; Sivaramakrishnan, G. Therapeutic clowns in pediatrics: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2016, 175, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulayoune, S.; Matabuena-Gómez-Limón, M.R.; Ventura-Puertos, P.E. Efectos fisiológicos y psicológicos de la risoterapia en la población pediátrica: Una revisión sistematizada. Actual. Med. 2020, 105, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, S.; Fareed, N.; MacEwan, S.R.; McAlearney, A.S. An Exploration of the Association between Inpatient Access to Tablets and Patient Satisfaction with Hospital Care. Perspect. Health Inf. Manag. 2019, 16. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6931050/ (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Barros, I.; Lourenço, M.; Nunes, E.; Charepe, Z. Intervenções de Enfermagem Promotoras da Adaptação da Criança/Jovem/Família à Hospitalização: Uma Scoping Review. Enf. Glob. 2021, 20. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/eg/v20n61/pt_1695-6141-eg-20-61-539.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez Rey, M.T.; Alonso Domínguez, Á.; Arnaiz García, A. Ocio ético: Afrontando la alienación y la deshumanización en los hospitales. Rev. Esp. Sociol (RES) 2019. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7375339 (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Rebecca, W.; Michael, J.S. A music therapy feasibility study with adults on a hospital neuroscience unit: Investigating service user technique choices and immediate effects on mood and pain. Arts Psychother. 2020, 67, 101585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørjasæter, K.B.; Davidson, L.; Hedlund, M.; Bjerkeset, O.; Ness, O. “I now have a life!” Lived experiences of participation in music and theater in a mental health hospital. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montross-Thomas, L.P.; Meier, E.A.; Reynolds-Norolahi, K.; Raskin, E.E.; Slater, D.; Mills, P.J.; MacElhern, L.; Kallenberg, G. Inpatients’ Preferences, Beliefs, and Stated Willingness to Pay for Complementary and Alternative Medicine Treatments. J Altern Complement Med. 2017, 23, 259–263. Available online: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/acm.2016.0288 (accessed on 20 April 2021). [CrossRef]

- Efrat-Triester, D.; Altman, D.; Friedmann, E.; Margalit, D.L.; Teodorescu, K. Exploring the usefulness of medical clowns in elevating satisfaction and reducing aggressive tendencies in pediatric and adult hospital wards. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltaci Goktas, S.; Yildiz, T.; Kosucu, S.N.; Ates, D. A hospital-based survey on the perception of music therapy among nurses and midwives. Eur. J. Ther. 2017, 22, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masetti, M.; Caires, S.; Brandão, D.; Vieira, D.A. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Questionnaire on the Health Staff’s Perceptions Regarding Doutores da Alegria’s Interventions. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomberg, J.; Raviv, A.; Fenig, E.; Meiri, N. Saving Costs for Hospitals Through Medical Clowning: A Study of Hospital Staff Perspectives on the Impact of the Medical Clown. Clin. Med. Insights Pediatr. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Venrooij, L.; Barnhoorn, P. Hospital clowning: A paediatrician’s view. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2017, 176, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, M.T.B.; de Sousa Lopes, M.; Âguia, M.R.P.S. La animación hospitalaria en el Centro Hospitalario de Chaves (Portugal). Campo Abierto. Rev. De Educ. 2011, 30, 95–106. Available online: https://mascvuex.unex.es/revistas/index.php/campoabierto/article/view/1511 (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Bermúdez Rey, M.T.; Martín Palacio, M.E.; Castellanos Cano, S. Animación Hospitalaria Con Pacientes Adultos En El Hospital La Fe De Valencia: Un Estudio De Necesidades. Bordón 2013, 65, 9–24. Available online: https://web.s.ebscohost.com/abstract?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=02105934&AN=88917348&h=vZIrcZHvph4c5pe5WZmzV1m0zc33SBJesseJOGkxSGJrzP%2bHVAXBDKFHk7VeoAxkSUkA%2f04bb0WYlLISEBhCcQ%3d%3d&crl=c&resultNs=AdminWebAuth&resultLocal=ErrCrlNotAuth&crlhashurl=login.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26profile%3dehost%26scope%3dsite%26authtype%3dcrawler%26jrnl%3d02105934%26AN%3d88917348 (accessed on 28 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Lechat, L.; Menschaert, L.; De Smedt, T.; Nijs, L.; Dhar, M.; Norga, K.; Toelen, J. Medical Art Therapy of the Future: Building an Interactive Virtual Underwater World in a Children’s Hospital. In Computational Intelligence in Music, Sound, Art and Design; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Losada, A.V.; Lacasta, M. Sentido del Humor y sus Beneficios en Salud. CdVS 2019, 12, 2–22. Available online: http://revistacdvs.uflo.edu.ar/index.php/CdVUFLO/article/view/172 (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Ford, K.; Courtney-Pratt, H.; Tesch, L.; Johnson, C. More than just clowns – Clown Doctor rounds and their impact for children, families and staff. J. Child. Health Care 2014, 18, 286–296. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1367493513490447 (accessed on 26 April 2021). [CrossRef]

| Database | Search String | Records Obtained |

|---|---|---|

| CINAHL | (leisure activities OR animation OR play therapy OR clown OR bibliotherapy OR art therapy OR music therapy) AND (hospitals) (lively OR entertainment OR laughter therapy) AND (hospitals) | 41 |

| PUBMED | 87 | |

| VIRTUAL HEALTH LIBRARY | 59 | |

| WEB OF SCIENCE | 86 | |

| COCHRANE LIBRARY | 28 | |

| DIALNET | 26 |

| Author Year Country | Types of Study Sample | Objective Intervention | Study Variable | Results and Conclusions | Quality, LE * and GR * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fallek et al. [24] 2020 United States | Quasi-experimental pre-post mixed methods study. A total of 150 patients over 18 years of age at Montefiore Medical Center from four inpatient units: palliative care, transplant, medical intensive care and general medicine. | To assess the effects of music therapy. To assess the feasibility of providing music therapy in the units and the patients’ interest, receptivity and satisfaction. Active participation, passive participation or a combination of both. |

|

| CASPe 9/10 SIGN LE: 3 GR: D |

| Scheufler et al. [25] 2020 United States | Experimental study of a three-treatment, three-intervention crossover design. A total of 40 females and 8 males aged 10–18 years with amplified pain who started an IIPT programme in a children’s hospital in the Midwestern United States. | To compare three music therapy interventions for anxiety and relaxation in young people with amplified pain. State Trait Inventory for Cognitive and Somatic Anxiety for Children and EVA scale. |

|

| CASPe 7/10 SIGN LE: 1- GR: B |

| Ford et al. [26] 2018 Australia | Qualitative study. A total of 22 patients with dementia or delirium, or both, in an intensive care unit for the elderly in a general hospital. In all, 18 healthcare staff: medical staff (n = 3); nurses (n = 7); allied health (n = 4); a medical student (n = 1) and ward support staff (n = 3). | To evaluate the impact of art in health programmes delivered within an acute older person’s unit. Observation of arts activities, semi-structured interviews with patients and relatives and focus groups with staff. |

|

| CASPe 9/10 SIGN: LE: 4 GR: D |

| Shella [27] 2018 United States | Longitudinal observational descriptive study. A total of 166 females and 29 males, aged 28–62 years, referred from a large urban teaching hospital with diagnoses of: cancer, neurological diseases, gastrointestinal problems, cardiac and vascular diseases, transplantation, post-surgical and orthopaedic procedures. | Perform art therapy to assess: mood, anxiety and pain. Roger’s Sad and Happy Face Scale. |

|

| STROBE 19/22 SIGN LE: 3 GR: D |

| Han et al. [28] 2017 Korea | Observational analytical studies: a case-control study. A total of 42 residents from two long-term care hospitals. | To investigate the effects of laughter therapy on depression and sleep among patients in two long-term care hospitals. MMSE-K (cognition), K-ADL (quality of life), GDSSF-K (depression) and PSQI-K (sleep) scales. |

|

| STROBE 21/22 SIGN LE: 2+ GR: C |

| Sridharan et al. [29] 2016 Fiyi | Systematic review and meta-analysis. A total of 18 randomised controlled trials (review) and 15 for meta-analysis. Children who were admitted to hospitalisation or underwent invasive procedures and their caregivers. | To compare the clinical utility of hospital clowns compared to the standard care in relieving fear, anxiety and pain in children. Review of studies. |

|

| PRISMA 25/27 SIGN LE: 2++ GR: B |

| Boulayoune et al. [30] 2020 Spain | Systematic review. A total of 15 articles on paediatric population. | To review the physiological and psychological effects of laughter therapy in the paediatric population. Review of studies. |

|

| PRISMA 27/27 SIGN LE: 2++ GR: B |

| Vink et al. [31] 2019 United States | Observational study An analytical cross-sectional case-control study. A total of 117 074 patients admitted to the six hospitals of the medical centre. Patients were excluded who were under 18 years old, who could not speak or read English or who were involuntarily detained, as were patients with less than one night’s stay in the hospital, patients with a principal psychiatric diagnosis or patients who were not alive at the time of discharge. | To explore the relationship between hospital access to tablets and patient satisfaction with hospital care. HCAHPS survey. |

|

| STROBE 19/22 SIGN LE: 2+ GR: C |

| Barros et al. [32] 2021 Portugal | Systematic review. A total of 14 articles. Patients under 18 and their family | To identify the process of child and family adaptation to hospitalisation and to map nursing interventions that promote child/young person/family adaptation to hospitalisation. Review of studies. |

|

| PRISMA 25/27 SIGN LE: 2++ GR: B |

| Bermúdez Rey et al. [33] 2019 Spain | Observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study. A total of 46 patients aged between 31 and 70, 35 accompanying persons and 26 healthcare staff, with patients in good physical and mental condition at the Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital in Santander (Cantabria). | To study the perception of the patients, families and professionals about the need to occupy the free time of hospitalised patients. Questionnaire of closed questions. |

|

| STROBE 20/22 SIGN LE: 3 GR: D |

| West et al. [34] 2020 United States | Observational study, descriptive longitudinal study. The 29 participants were adults receiving care on a general neuroscience unit within a University-affiliated hospital in the Midwestern region of the United States. | To study the frequency of the user’s choice of the music therapy technique. Additionally, to study the effects on mood and pain in adults receiving music therapy. Mood (QMS) and pain (Likert) scales. |

|

| STROBE 21/22 SIGN LE: 3 GR: D |

| Ørjasæter et al. [35] 2018 Norway | Qualitative study, hermeneutic-phenomenological analysis. A total of 11 adult participants in a music and theater workshop carried out in a Norwegian mental health hospital. | To explore experiences of participation in music and drama among people with long-term mental illness. Open interviews. |

|

| CASPe 10/10 SIGN LE: 4 GR: D |

| Montross-Thomas et al. [36] 2017 United States | Cross-sectional descriptive observational study. Adult patients (n = 100), ranging in age from 19–95 years, were recruited during their hospitalization in the University of California, San Diego, Healthcare System. | To show perspectives on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) services. Closed response interview. |

|

| STROBE 19/22 SIGN LE: 3 GR: D |

| Efrat-Triester et al. [37] 2021 Israel | Cross-sectional descriptive observational study. A total of 495 participants, made up of 88 healthcare workers, 20 medical clowns and 387 health consumers. | Exploring the usefulness of clowns. Survey. |

|

| STROBE 20/22 SIGN LE: 3 GR: D |

| Baltacı GÖKTAŞ et al. [38] 2017 Turkey | Cross-sectional descriptive observational study. A total of 225 nurses and midwives | To determine the knowledge, understanding, behaviour and practices of music therapy among nurses and midwives. Survey. |

|

| STROBE 18/22 SIGN LE: 3 GR: D |

| Masetti et al. [39] 2019 Brazil | Cross-sectional descriptive observational study. A total of 567 professionals from 13 public hospitals | To analyse health professionals’ perception of “Doutores da Alegria’s” interventions using a questionnaire. Questionnaire. |

|

| STROBE 20/22 SIGN LE: 3 GR: D |

| Gomberg et al. [40] 2020 Israel | Qualitative grounded theory study. A total of 35 subjects were interviewed with 35 doctors, nurses and technicians at the Davidoff oncology ward of Beilinson Hospital in Petah Tikva, Israel. | To explore hospital staff perspectives on the impact of medical clowning. Individual semi-structured interviews. |

|

| CASPe 9/10 SIGN LE: 4 GR: D |

| Van Venrooijy et al. [41] 2017 Netherlands | Qualitative study. A total of 14 paediatricians of the paediatric departments of Haga Hospital The Hague and Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands, to evaluate the effect of hospital clowning in children between 3 and 12 years of age. | To investigate the current situation of hospital clowns from the perspective of paediatricians and paediatric residents. Focus groups. |

|

| CASPe 8/10 SIGN LE: 4 GR: D |

| Programme | Interventions | Age | Activities | Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Music | Passive music sessions [24,25] | Over 10 |

|

|

| Active music sessions [24,25,26,32] | For all ages |

| ||

| Art | Painting [26,27,32] | For all ages |

|

|

| Beads [27] | Those 28–62 years old |

| ||

| Handicraft works [27] |

| |||

| Room decoration [26] | Elderly people |

| ||

| Illustration/drawing for the patient [26] |

| |||

| Humour | Hospital clown [29,30] | Children and their caregivers |

|

|

| Laughter therapy sessions [28,32] | Under 18 |

|

| |

| Electronic | Tablets [31] | Over 18 |

|

|

| Computers [32] | Under 18 |

| ||

| Accompaniment | Accompaniment by animals [32] | Those under 18 |

|

|

| Accompaniment by people [33] | Adults |

|

| |

| Others | [28,33] | For all ages |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adam-Castelló, P.; Sosa-Palanca, E.M.; Celda-Belinchón, L.; García-Martínez, P.; Mármol-López, M.I.; Saus-Ortega, C. Leisure Programmes in Hospitalised People: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043268

Adam-Castelló P, Sosa-Palanca EM, Celda-Belinchón L, García-Martínez P, Mármol-López MI, Saus-Ortega C. Leisure Programmes in Hospitalised People: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043268

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdam-Castelló, Paula, Eva María Sosa-Palanca, Luis Celda-Belinchón, Pedro García-Martínez, María Isabel Mármol-López, and Carlos Saus-Ortega. 2023. "Leisure Programmes in Hospitalised People: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043268

APA StyleAdam-Castelló, P., Sosa-Palanca, E. M., Celda-Belinchón, L., García-Martínez, P., Mármol-López, M. I., & Saus-Ortega, C. (2023). Leisure Programmes in Hospitalised People: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043268