The Associations between Meeting 24-Hour Movement Guidelines (24-HMG) and Mental Health in Adolescents—Cross Sectional Evidence from China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Physical Activity Time

2.2.2. Screen Time

2.2.3. Sleep Time

2.2.4. Depression and Anxiety Scores

2.2.5. Covariates

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

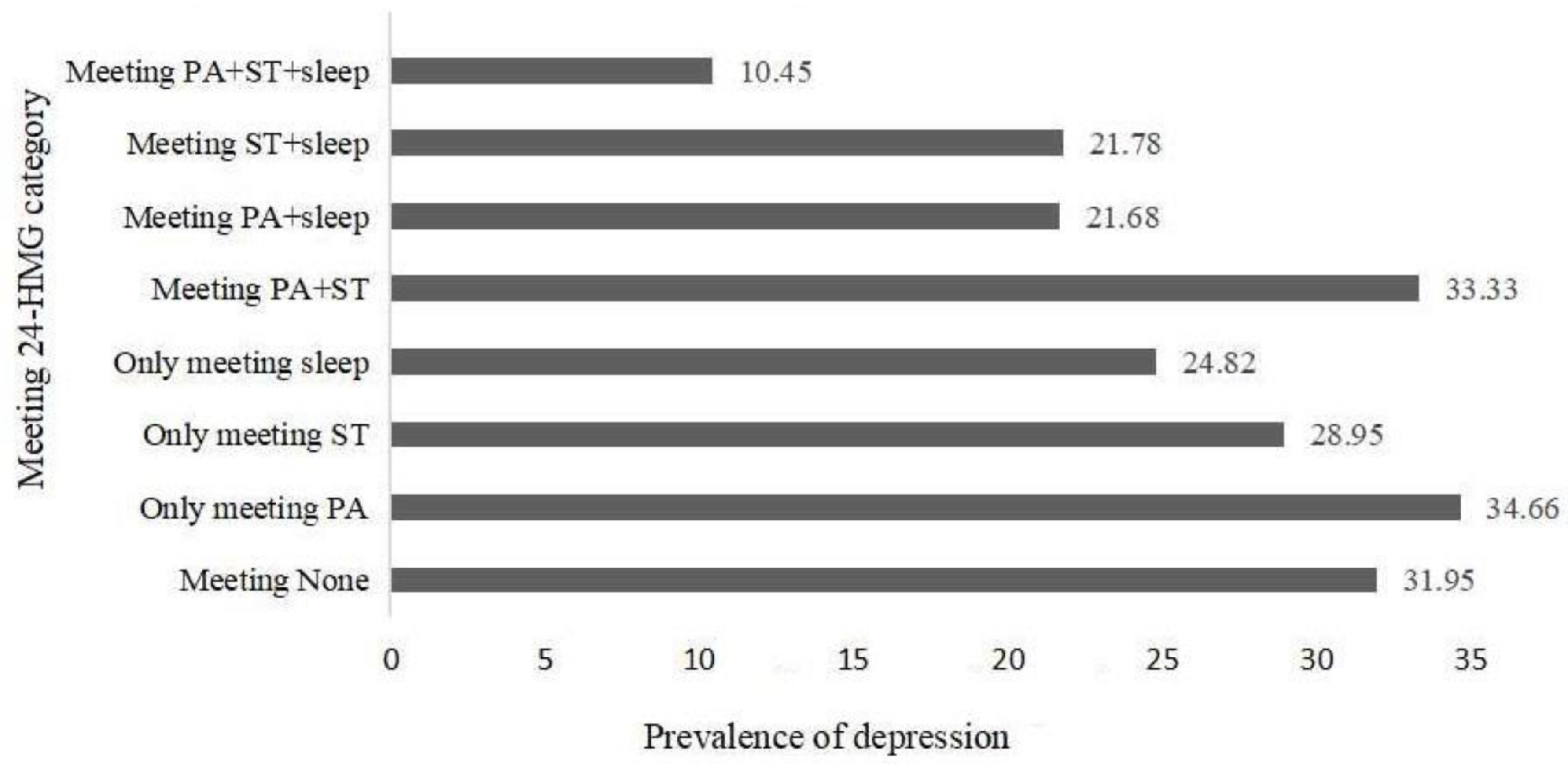

3.2. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety among Adolescents in Different 24-HMG Categories

3.3. Meeting One of the 24-HMG Recommendations in Relation to Anxiety and Depression

3.4. Meeting Two of the 24-HMG Recommendations in Relation to Anxiety and Depression

3.5. Meeting Three of the 24-HMG Recommendations in Relation to Anxiety and Depression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Asare, M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: A review of reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 45, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babic, M.J.; Smith, J.J.; Morgan, P.J.; Eather, N.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Lubans, D.R. Longitudinal associations between changes in screen-time and mental health outcomes in adolescents. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2017, 12, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Paksarian, D.; Lamers, F.; Hickie, I.B.; He, J.; Merikangas, K.R. Sleep Patterns and Mental Health Correlates in US Adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2017, 182, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.P.; Connor Gorber, S.; Dinh, T.; Duggan, M.; Faulkner, G.; Gray, C.E.; Gruber, R.; Janson, K.; et al. Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth: An integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S311–S327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Lee, E.-Y.; Tremblay, M.S. Meeting 24-h movement guidelines and associations with health related quality of life of Australian adolescents. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 24, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollo, S.; Antsygina, O.; Tremblay, M.S. The whole day matters: Understanding 24-hour movement guideline adherence and relationships with health indicators across the lifespan. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga, H.; Standage, M.; Tremblay, M.; Katzmarzyk, P.; Hu, G.; Kuriyan, R.; Maher, C.; Maia, J.; Olds, T.; Sarmiento, O.L.; et al. Associations between meeting combinations of 24-h movement guidelines and health-related quality of life in children from 12 countries. Public Health 2017, 153, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, A.-M.; Tremblay, M.S.; Carson, S.; Veldman, S.L.C.; Cliff, D.; Vella, S.; Chong, K.H.; Nacher, M.; Cruz, B.D.P.; Ellis, Y.; et al. Comparing and assessing physical activity guidelines for children and adolescents: A systematic literature review and analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, J.; Tremblay, M.; Brazo-Sayavera, J. Changes in Healthy Behaviors and Meeting 24-h Movement Guidelines in Spanish and Brazilian Preschoolers, Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Children 2021, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Ma, J.; Harada, K.; Lee, S.; Gu, Y. Associations between Adherence to Combinations of 24-h Movement Guidelines and Overweight and Obesity in Japanese Preschool Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, R.D.F.; Gilbert, J.-A.; Lemoyne, J.; Mathieu, M.-E. Better health indicators of FitSpirit participants meeting 24-h movement guidelines for Canadian children and youth. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 36, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorey, S.; Ng, E.D.; Wong, C.H.J. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 61, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erskine, H.E.; Baxter, A.J.; Patton, G.; Moffitt, T.E.; Patel, V.; Whiteford, H.A.; Scott, J.G. The global coverage of prevalence data for mental disorders in children and adolescents. Epidemiology Psychiatr. Sci. 2016, 26, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiles, N.J.; Jones, G.T.; Haase, A.M.; Lawlor, D.A.; Macfarlane, G.J.; Lewis, G. Physical activity and emotional problems amongst adolescents. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008, 43, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothon, C.; Edwards, P.; Bhui, K.; Viner, R.M.; Taylor, S.; A Stansfeld, S. Physical activity and depressive symptoms in adolescents: A prospective study. BMC Med. 2010, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberle, E.; Ji, X.R.; Kerai, S.; Guhn, M.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Gadermann, A.M. Screen time and extracurricular activities as risk and protective factors for mental health in adolescence: A population-level study. Prev. Med. 2020, 141, 106291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K. Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuligni, A.J.; Arruda, E.H.; Krull, J.L.; Gonzales, N.A. Adolescent Sleep Duration, Variability, and Peak Levels of Achievement and Mental Health. Child Dev. 2017, 89, e18–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S.C.; Jos, A.M.; Erwin, C.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, X.K.; Lo, J.C.; Chee, M.; Gooley, J.J. Associations of sleep duration on school nights with self-rated health, overweight, and depression symptoms in adolescents: Problems and possible solutions. Sleep Med. 2018, 60, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, C.P.; MacDonncha, C.; Herring, M.P. Brief report: Associations of physical activity with anxiety and depression symptoms and status among adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2017, 55, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougharbel, F.; Goldfield, G.S. Psychological Correlates of Sedentary Screen Time Behaviour Among Children and Adolescents: A Narrative Review. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2020, 9, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, K.T.; Desai, A.; Field, J.; Miller, L.E.; Rausch, J.; Beebe, D.W. Sleep restriction worsens mood and emotion regulation in adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojio, Y.; Kishi, A.; Sasaki, T.; Togo, F. Association of depressive symptoms with habitual sleep duration and sleep timing in junior high school students. Chrono- Int. 2020, 37, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga, H.; Colman, I.; Goldfield, G.S.; Janssen, I.; Wang, J.; Podinic, I.; Tremblay, M.S.; Saunders, T.J.; Sampson, M.; Chaput, J.-P. Combinations of physical activity, sedentary time, and sleep duration and their associations with depressive symptoms and other mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Cheval, B.; Yu, Q.; Hossain, M.; Chen, S.-T.; Taylor, A.; Bao, R.; Doig, S.; Li, J.; Wang, T.; et al. Associations of 24-Hour Movement Behavior with Depressive Symptoms and Anxiety in Children: Cross-Sectional Findings from a Chinese Sample. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.; Parrish, A.-M.; Cliff, D.; Dumuid, D.; Okely, A. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Associations between 24-Hour Movement Behaviours, Recreational Screen Use and Psychosocial Health Outcomes in Children: A Compositional Data Analysis Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xue, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y. Parental Expectations and Child Screen and Academic Sedentary Behaviors in China. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.; Chaput, J.P.; Giangregorio, L.M.; Janssen, I.; Saunders, T.J.; Kho, M.E.; Poitras, V.J.; Tomasone, J.R.; El-Kotob, R.; McLaughlin, E.C.; et al. Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Adults aged 18–64 years and Adults aged 65 years or older: An integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 45, S57–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Lu, Y.; Song, H. The Effect of Teacher Gender on Students’ Academic and Noncognitive Outcomes. J. Labor Econ. 2018, 36, 743–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N. The GAD-7 questionnaire. Occup. Med. 2014, 64, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.H.; Li, S.P.; Yang, W.N.; Liu, C.F. The impact of classroom girl ratio on students’ psychological health-Based on data from the China Education Tracking Survey (CEPS). Peking Univ. Educ. Rev. 2021, 19, 19–40+188. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Gao, L.; Chiu, D.T.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. Overweight and Obesity impair academic performance in adolescence: A national cohort study of 10,279 adolescents in China. Obesity 2020, 28, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health Commission. Screening for Overweight and Obesity among School-Age Children and Adolescents; National Health Commission: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Yu, Q.; Hossain, M.; Doig, S.; Bao, R.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, J.; Luo, X.; Yang, J.; Kramer, A.F.; et al. Meeting 24-h Movement Guidelines is Related to Better Academic Achievement: Findings from the YRBS 2019 Cycle. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2022, 24, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, I.; Roberts, K.C.; Thompson, W. Is adherence to the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Behaviour Guidelines for Children and Youth associated with improved indicators of physical, mental, and social health? Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 42, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Gil, J.F.; Roman-Viñas, B.; Aznar, S.; Tremblay, M.S. Meeting 24-h movement guidelines: Prevalence, correlates, and associations with socioemotional behavior in Spanish minors. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2022, 32, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-T.; Liu, Y.; Tremblay, M.S.; Hong, J.-T.; Tang, Y.; Cao, Z.-B.; Zhuang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Meeting 24-h movement guidelines: Prevalence, correlates, and the relationships with overweight and obesity among Chinese children and adolescents. J. Sport Health Sci. 2021, 10, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga, H.; Chaput, J.-P.; Goldfield, G.S.; Janssen, I.; Wang, J.; Hamilton, H.A.; Colman, I. 24-hour movement guidelines and suicidality among adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, L.; Zhu, X.; Haegele, J.; Wen, Y. Movement in High School: Proportion of Chinese Adolescents Meeting 24-Hour Movement Guidelines. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, F.; Cappa, C.; Madans, J. Anxiety and Depression Signs Among Adolescents in 26 Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Prevalence and Association with Functional Difficulties. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 72, S79–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikangas, K.R.; He, J.-P.; Burstein, M.; Swanson, S.A.; Avenevoli, S.; Cui, L.; Benjet, C.; Georgiades, K.; Swendsen, J. Lifetime Prevalence of Mental Disorders in U.S. Adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 49, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Mazidi, M.; Li, K.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Kirwan, R.; Zhou, H.; Yan, N.; Rahman, A.; Wang, W.; et al. Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Tang, S.; Ren, Z.; Wong, D.F.K. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among adolescents in secondary school in mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 245, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patte, K.A.; Faulkner, G.; Qian, W.; Duncan, M.; Leatherdale, S.T. Are one-year changes in adherence to the 24-hour movement guidelines associated with depressive symptoms among youth? BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Haegele, J.A.; Healy, S. Movement and mental health: Behavioral correlates of anxiety and depression among children of 6–17 years old in the U.S. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, P.K.; Roberts, R.; Harris, J.K. A Systematic Review Assessing Bidirectionality between Sleep Disturbances, Anxiety, and Depression. Sleep 2013, 36, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A.M.; Sadeh, A. Sleep, emotional and behavioral difficulties in children and adolescents. Sleep Med. Rev. 2012, 16, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.O.; Roth, T.; Schultz, L.; Breslau, N. Epidemiology of DSM-IV Insomnia in Adolescence: Lifetime Prevalence, Chronicity, and an Emergent Gender Difference. Pediatrics 2006, 117, e247–e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Hatzinger, M.; Beck, J.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E. Perceived parenting styles, personality traits and sleep patterns in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2009, 32, 1189–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, R.E.; Harvey, A.G. Sleep in Children and Adolescents with Behavioral and Emotional Disorders. Sleep Med. Clin. 2007, 2, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, R.E. The regulation of sleep and arousal: Development and psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 1996, 8, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R.; Palmer, C.A.; Jackson, C.; Farris, S.G.; Alfano, C.A. Impact of sleep restriction versus idealized sleep on emotional experience, reactivity and regulation in healthy adolescents. J. Sleep Res. 2017, 26, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredriksen, K.; Rhodes, J.; Reddy, R.; Way, N. Sleepless in Chicago: Tracking the Effects of Adolescent Sleep Loss During the Middle School Years. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagaspe, P.; Sanchez-Ortuno, M.; Charles, A.; Taillard, J.; Valtat, C.; Bioulac, B.; Philip, P. Effects of sleep deprivation on Color-Word, Emotional, and Specific Stroop interference and on self-reported anxiety. Brain Cogn. 2006, 60, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, K.A.; Harvey, A.G. Hypersomnia across mood disorders: A review and synthesis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2009, 13, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Physical Activity Guidelines | Sleep Guidelines | Sedentary Guidelines Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| An accumulation of at least 60 min per day of moderate to vigorous physical activity involving a variety of aerobic activities. | Uninterrupted 9 to 11 h of sleep per night for those aged 5–13 years and 8 to 10 h per night for those aged 14–17 years | No more than 2 h per day of recreational screen time |

| Vigorous physical activities and muscle and bone strengthening activities should each be incorporated at least 3 days per week | Consistent bed and wake-up times | Limited sitting for extended periods |

| Several hours of a variety of structured and unstructured light physical activities |

| Mean ± SD/% | Gender Differences | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 9420) | Boys (n = 5163) | Girls (n = 4257) | t/X2 | p | |

| Age(y) | 14.53 ± 0.69 | 14.60 ± 0.67 | 14.45 ± 0.71 | 9.821 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | 106.215 | <0.001 | |||

| Han | 87.08 | 83.85 | 91.00 | ||

| Non-Han | 12.92 | 16.15 | 9.00 | ||

| Single child | 19.433 | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 44.86 | 47.06 | 42.42 | ||

| No | 55.14 | 52.94 | 57.58 | ||

| Residence | 4.134 | 0.042 | |||

| City | 47.78 | 46.76 | 48.91 | ||

| Rural | 52.22 | 53.24 | 51.09 | ||

| Father’s highest education | 34.382 | <0.001 | |||

| ≤Junior middle school | 58.52 | 61.15 | 55.34 | ||

| Senior middle school or vocational school | 25.71 | 24.50 | 27.18 | ||

| ≥College | 15.76 | 14.35 | 17.48 | ||

| Mother’s highest education | 18.960 | <0.001 | |||

| ≤Junior middle school | 64.66 | 64.49 | 62.44 | ||

| Senior middle school or vocational school | 22.11 | 21.36 | 23.02 | ||

| ≥College | 13.23 | 12.14 | 14.54 | ||

| Perceived household economic status | 16.672 | <0.001 | |||

| Lower income | 20.69 | 22.03 | 19.19 | ||

| Middle class | 73.45 | 71.64 | 75.45 | ||

| Wealthy | 5.87 | 6.33 | 5.36 | ||

| BMI | 48.771 | <0.001 | |||

| Below overweight | 87.28 | 85.11 | 89.92 | ||

| Above overweight | 12.72 | 14.89 | 10.08 | ||

| Meeting PA | 130.358 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 94.61 | 92.19 | 97.53 | ||

| Yes | 5.31 | 7.81 | 2.47 | ||

| Meeting ST | 63.635 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 79.68 | 82.68 | 76.04 | ||

| Yes | 20.32 | 17.32 | 23.96 | ||

| Meeting Sleep | 53.230 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 39.46 | 39.12 | 43.50 | ||

| Yes | 60.54 | 63.88 | 56.50 | ||

| Meeting the 24-HMG category | 254.361 | <0.001 | |||

| Meeting None | 28.70 | 26.28 | 31.64 | ||

| Only meeting PA | 1.87 | 2.61 | 0.96 | ||

| Only meeting ST | 8.47 | 6.82 | 10.48 | ||

| Only meeting sleep | 46.71 | 50.03 | 42.68 | ||

| Meeting PA + ST | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.42 | ||

| Meeting PA + sleep | 2.40 | 3.76 | 0.75 | ||

| Meeting ST + sleep | 10.72 | 9.06 | 12.73 | ||

| Meeting PA + ST + sleep | 0.71 | 1.03 | 0.33 | ||

| Depression | 0.122 | 0.726 | |||

| No | 73.07 | 72.92 | 73.24 | ||

| Yes | 26.93 | 27.08 | 26.76 | ||

| Anxiety | 0.897 | 0.344 | |||

| No | 70.56 | 70.97 | 70.07 | ||

| Yes | 29.44 | 29.03 | 29.93 | ||

| Total | Boys | Girls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| Depression | ||||||

| Only meeting PA | 0.97 (0.69~1.37) | 0.890 | 0.97 (0.66~1.45) | 0.918 | 0.85 (0.42~1.71) | 0.663 |

| Only meeting ST | 0.85 (0.71~1.02) | 0.073 | 0.83 (0.63~1.09) | 0.186 | 0.87 (0.69~1.10) | 0.259 |

| Only meeting sleep | 0.65 (0.58~0.73) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.51~0.70) | <0.001 | 0.70 (0.60~0.82) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | ||||||

| Only meeting PA | 1.14 (0.82~1.60) | 0.418 | 1.17 (0.79~1.73) | 0.409 | 0.96 (0.48~1.92) | 0.395 |

| Only meeting ST | 0.86 (0.72~1.03) | 0.124 | 0.80 (0.61~1.06) | 0.137 | 0.91 (0.72~1.16) | 0.429 |

| Only meeting sleep | 0.68 (0.61~0.76) | <0.001 | 0.64 (0.54~0.74) | <0.001 | 0.73 (0.62~0.86) | <0.001 |

| Total | Boys | Girls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| Depression | ||||||

| Meeting PA+ST | 0.45 (0.19~1.03) | 0.060 | 0.68 (0.24~1.92) | 0.472 | 0.23 (0.05~1.04) | 0.058 |

| Meeting PA + sleep | 0.52 (0.37~0.74) | <0.001 | 0.55 (0.38~0.79) | 0.002 | 0.29 (0.10~0.83) | 0.022 |

| Meeting ST + sleep | 0.46 (0.35~0.51) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.32~0.56) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.33~0.54) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | ||||||

| Meeting PA + ST | 1.14 (0.57~2.26) | 0.699 | 1.41 (0.56~3.54) | 0.466 | 0.88 (0.31~2.49) | 0.057 |

| Meeting PA + sleep | 0.59 (0.42~0.83) | 0.003 | 0.64 (0.44~0.93) | 0.019 | 0.24 (0.07~0.79) | 0.021 |

| Meeting ST + sleep | 0.57 (0.48~0.48) | <0.001 | 0.54 (0.41~0.71) | <0.001 | 0.59 (0.47~0.76) | <0.001 |

| Total | Boys | Girls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| Depression | ||||||

| Meeting PA + ST + sleep | 0.27 (0.13~0.58) | 0.001 | 0.20 (0.08~0.52) | 0.001 | 0.52 (0.16~2.19) | 0.006 |

| Anxiety | ||||||

| Meeting PA + ST + sleep | 0.18 (0.07~0.45) | <0.001 | 0.08 (0.02~0.34) | 0.001 | 0.60 (0.16~2.19) | 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, L.; Zeng, X.; Cao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wen, S.; Tang, K.; Ding, L.; Wang, X.; Song, N. The Associations between Meeting 24-Hour Movement Guidelines (24-HMG) and Mental Health in Adolescents—Cross Sectional Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043167

Luo L, Zeng X, Cao Y, Hu Y, Wen S, Tang K, Ding L, Wang X, Song N. The Associations between Meeting 24-Hour Movement Guidelines (24-HMG) and Mental Health in Adolescents—Cross Sectional Evidence from China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043167

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Lin, Xiaojin Zeng, Yunxia Cao, Yulong Hu, Shaojing Wen, Kaiqi Tang, Lina Ding, Xiangfei Wang, and Naiqing Song. 2023. "The Associations between Meeting 24-Hour Movement Guidelines (24-HMG) and Mental Health in Adolescents—Cross Sectional Evidence from China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043167

APA StyleLuo, L., Zeng, X., Cao, Y., Hu, Y., Wen, S., Tang, K., Ding, L., Wang, X., & Song, N. (2023). The Associations between Meeting 24-Hour Movement Guidelines (24-HMG) and Mental Health in Adolescents—Cross Sectional Evidence from China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043167