Insights from COVID-19: Reflecting on the Promotion of Long-Term Health Policies in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Long-Term Health Policy Promotion

2.2. Development and Promotion of the Healthy China Policy

2.3. Impact of Health Policy on Public Mental Health during the Pandemic

2.4. Relationship between Health Policy and Smart Healthcare during the Pandemic

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data and Participants

3.1.1. Data Source

3.1.2. Questionnaire Preparation and Survey Method

3.1.3. Statistical Analysis

3.2. Variables

3.3. Data Analysis Approach

4. Results

4.1. Overview of HCI Understanding Level

4.2. Overview of Smart Healthcare Familiarity Level

4.3. The Relationship between the HCI and Smart Healthcare

4.4. Impact of Demographic Factors on HCI

4.5. Impact of Health Information on HCI

4.6. Respondents’ Channels of Access to Health Information

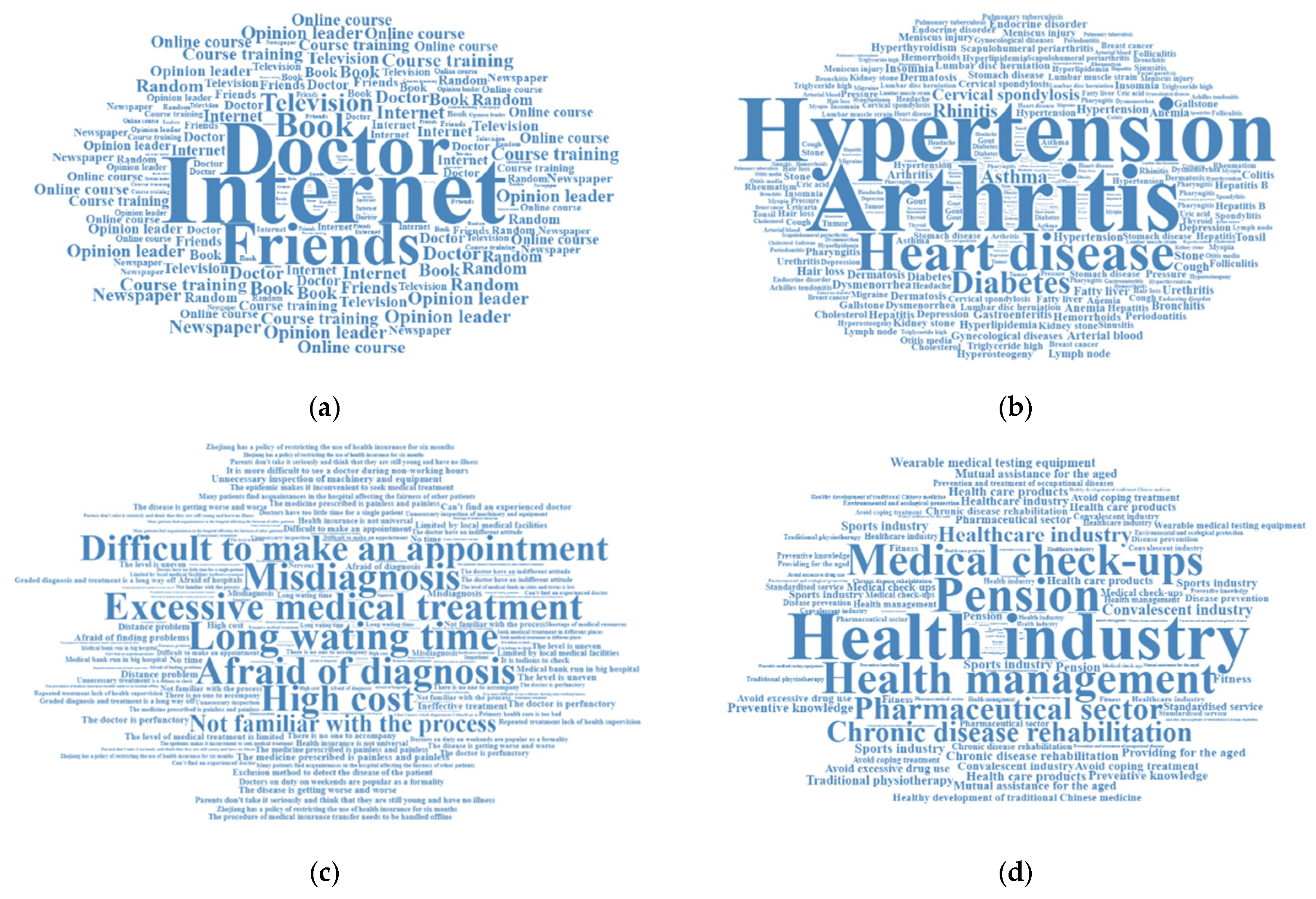

4.7. Respondents’ Topics of Concern

5. Discussion

5.1. HCI Promotion Is Insufficient

5.1.1. Community Involvement in Policy Promotion

5.1.2. Smart Healthcare Improves Access to Information

5.1.3. Recommendations in Relation to Policy Promotion

5.2. Limitations and Further Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Health China Action Promotion Committee Office. Action Plan in Healthy China Initiaive. 2021. Available online: https://www.jkzgxd.cn/fifteenActions (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Tan, X.; Liu, X.; Shao, H. Healthy China 2030: A Vision for Health Care. Value Health Reg. Issues 2017, 12, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Su, M. A preliminary assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on environment—A case study of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Kumar, N.; Shah, R. Role of IoT to avoid spreading of COVID-19. Int. J. Intell. Netw. 2020, 1, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Las Heras-Pedrosa, C.; Sánchez-Núñez, P.; Peláez, J.I. Sentiment analysis and emotion understanding during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain and its impact on digital ecosystems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bambra, C.; Riordan, R.; Ford, J.; Matthews, F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, J.; Meadows, M.E.; Liu, Y.; Hua, T.; Fu, B. A systematic approach is needed to contain COVID-19 globally. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yao, M.; Meng, C.; Claramunt, C. Risk assessment of the overseas imported COVID-19 of ocean-going ships based on AIS and infection data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.; Newman, E. McKinsey on Healthcare: 2020 Year in Review Healthcare Systems & Services; McKinsey: Grand Ledge, MI, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/mckinsey-on-healthcare-2020-year-in-review (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- National Health Service. The NHS Long Term Plan; NHS: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, A.; Asbridge, J. The NHS Long Term Plan (2019)—Is it person-centered? Eur. J. Pers. Cent. Healthc. 2019, 7, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/factsheets/factsheet-hp2030.htm (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Mason, J.O.; McGinnis, J.M. “Healthy People 2000”: An overview of the national health promotion and disease prevention objectives. Public Health Rep. 1990, 105, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hartwig, K.A.; Dunville, R.L.; Kim, M.H.; Levy, B.; Zaharek, M.M.; Njike, V.Y.; Katz, D.L. Promoting healthy people 2010 through small grants. Health Promot. Pract. 2009, 10, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Insititute of Health and Nutrition. The Second Term of National Health Promotion Movement in the Twenty First Century. 2021. Available online: https://www.nibiohn.go.jp/eiken/kenkounippon21/en/zoushinkeikaku/index.html (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Tsuji, I. Current status and issues concerning Health Japan 21 (second term). Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78 (Suppl. S2), 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustace, B. China’s health reform: 10 years on. Lancet 2019, 4, e245–e255. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, F.; Liu, Y.; Willett, W. Preventing chronic diseases by promoting healthy diet and lifestyle: Public policy implications for China. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, W.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chai, P.; Goss, J. Research in health policy making in China: Out-of-pocket payments in Healthy China 2030. BMJ 2018, 360, k234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, F.; Harmer, P. Healthy China 2030: Moving from blueprint to action with a new focus on public health. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schippers, M.C. For the greater good? The devastating ripple effects of the COVID-19 crisis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 577740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Friedman, M.J.; Watson, P.J.; Byrne, C.M.; Diaz, E.; Kaniasty, K. 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry 2002, 65, 207–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebri, V.; Cincidda, C.; Savioni, L.; Ongaro, G.; Pravettoni, G. Worry during the initial height of the COVID-19 crisis in an Italian sample. J. Gen. Psychol. 2021, 148, 327–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettman, C.K.; Abdalla, S.M.; Cohen, G.H.; Sampson, L.; Vivier, P.M.; Galea, S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2019686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, E. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19)—China, 2020. China CDC Wkly. 2020, 2, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/strategic-preparedness-and-response-plan-for-the-new-coronavirus (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- National Health Commission of China. Principles of the Emergency Psychological Crisis Interventions for the New Coronavirus Pneumonia. 2020. Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3577/202001/6adc08b966594253b2b791be5c3b9467 (accessed on 27 January 2020). (In Chinese)

- Zhang, N. Risk perception, mental health distress, and flourishing during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: The role of positive and negative affect. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Xu, J.; Huang, S.; Li, P.; Lu, C.; Xie, S. Risk perception and depression in public health crises: Evidence from the COVID-19 crisis in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, D.; Luo, Q.; Ritchie, B.W. Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongaro, G.; Cincidda, C.; Sebri, V.; Savioni, L.; Triberti, S.; Ferrucci, R.; Poletti, B.; Dell’Osso, B.; Pravettoni, G. A 6-month follow-up study on worry and its impact on well-being during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in an Italian sample. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 703214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehl, A.K.; Schene, A.; Kohn, N.; Fernández, G. Maladaptive emotion regulation strategies in a vulnerable population predict increased anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: A pseudo-prospective study. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 4, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.L.; Varilly, H.; Cohn, J.; Wightwick, G.R. Preface: Technologies for a smarter planet. IBM J. Res. Dev. 2010, 54, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Yang, W.; Le Grange, J.M.; Wang, P.; Huang, W.; Ye, Z. Smart healthcare: Making medical care more intelligent. Glob. Health J. 2019, 3, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.-B. Application of personal-oriented digital technology in preventing transmission of COVID-19, China. Ir. J. Med. Sci. (1971-) 2020, 189, 1145–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Dai, D.; Hou, S.; Liu, W.; Gao, F.; Xu, D.; Hu, Y. Thinking on the informatization development of China’s healthcare system in the post-COVID-19 era. Intell. Med. 2021, 1, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babrow, A.S.; Kasch, C.R.; Ford, L.A. The many meanings of uncertainty in illness: Toward a systematic accounting. Health Commun. 1998, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babrow, A.S.; Kline, K.N. From “reducing” to “coping with” uncertainty: Reconceptualizing the central challenge in breast self-exams. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 1805–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, B.F.; Brockmann, D. Effective containment explains subexponential growth in recent confirmed COVID-19 cases in China. Science 2020, 368, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2021. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, J.; Shi, W.; Wu, J. Comparison of Salt-Related Knowledge and Behaviors Status of WeChat Users between 2019 and 2020. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, R.A. Measuring and Interpreting Subjective Wellbeing in Different Cultural Contexts: A Review and Way Forward; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, C.E.; Leifheit, K.M.; McGinty, E.E.; Levine, A.S.; Barry, C.L.; Linton, S.L. Public Support for Policies to Increase Housing Stability During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 61, 919–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagidullin, M.; Aziz, N.; Kozhakhmet, S. Government policies and attitudes to social media use among users in Turkey: The role of awareness of policies, political involvement, online trust, and party identification. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimerl, F.; Lohmann, S.; Lange, S.; Ertl, T. Word cloud explorer: Text analytics based on word clouds. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1833–1842. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, A.C.; Windmeijer, F.A. An R-squared measure of goodness of fit for some common nonlinear regression models. J. Econom. 1997, 77, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Zou, Z.; Song, Y.; Hu, P.; Luo, D.; Wen, B.; Gao, D.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Ma, Y.; et al. Adolescent health and healthy China 2030: A review. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, S24–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozur, P.; Zhong, R.; Krolik, A. ‘In Coronavirus Fight, China Gives Citizens a Color Code, With Red Flags’. The New York Times, 2 March 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/01/business/china-coronavirus-surveillance.html (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Magklaras, G.; López-Bojórquez, L.N. A review of information security aspects of the emerging COVID-19 contact tracing mobile phone applications. In International Symposium on Human Aspects of Information Security and Assurance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, F. COVID-19 and Health Code: How Digital Platforms Tackle the Pandemic in China. Soc. Media Soc. 2020, 6, 2056305120947657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollmann, K.; van der Keylen, P.; Tomandl, J.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Sofroniou, M.; Maun, A.; Voigt-Radloff, S. The information needs of internet users and their requirements for online health information—A scoping review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 1904–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cao, M.; Cheng, L.; Zhai, K.; Zhao, X.; De Vos, J. Exploring the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in travel behaviour: A qualitative study. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 11, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Policy/Program | Policy Publisher(s) | Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy China 2020 program (2009) | Ministry of Health (Now NHC) |

|

| Healthy China 2030 Planning Outline (2016) | Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and State Council of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) |

|

| HCI (2019–2030) Action plan for Healthy China 2030 policy | State Council of the PRC |

|

| Parameter | China Statistical Yearbook 2020 | Research Sample | Num. of Cases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 48.91% | 47.11% | 1172 |

| Location | Northern | 12.51% | 13.87% | 345 |

| Northeastern | 7.69% | 6.15% | 153 | |

| Eastern | 29.48% | 34.81% | 866 | |

| Central & Southern | 28.43% | 25.40% | 632 | |

| Southwestern | 14.50% | 13.22% | 329 | |

| Northwestern | 7.38% | 6.55% | 163 | |

| Age (18 years or older) | ≤19 | 3.49% | 2.85% | 71 |

| 20–29 | 16.21% | 18.45% | 459 | |

| 30–39 | 19.43% | 21.26% | 529 | |

| 40–49 | 19.54% | 22.63% | 563 | |

| ≥50 | 41.33% | 34.81% | 866 | |

| Average | 42.4 | 41.31 | / | |

| Income | Average disposable household income | 95,672.8 CNY | 96,298 CNY | / |

| Ethnicity | Han | 91.11% | 93.77% | 2333 |

| Variables | Mean | Std Dev | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | ||||

| HCI | 2.20 | 0.93 | 1 | 5 |

| Explanatory variables—Group 1 | ||||

| Smart Healthcare | 2.66 | 1.18 | 1 | 5 |

| Explanatory variables—Group 2 | ||||

| Assisting diagnosis and treatment | 2.70 | 0.91 | 1 | 5 |

| Health management | 3.08 | 1.10 | 1 | 5 |

| Disease prevention and risk monitoring | 3.23 | 1.04 | 1 | 5 |

| Assisting drug research | 3.11 | 0.94 | 1 | 5 |

| Control variables | ||||

| Demographic factors | ||||

| Female | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 2.64 | 0.90 | 1 | 5 |

| Education level | 3.52 | 1.04 | 1 | 5 |

| Urban | 0.62 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 |

| Average annual household income | 2.56 | 1.13 | 1 | 5 |

| Health status information | ||||

| Current health status better | 0.81 | 0.39 | 0 | 1 |

| Feeling unwell for less than 15 days | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ||||

| Group 1 | ||||

| Smart Healthcare | 0.251 *** (0.032) | 0.259 *** (0.033) | ||

| Group 2 | ||||

| Assisting diagnosis and treatment | 0.270 *** (0.042) | 0.364 *** (0.043) | ||

| Health management | 0.080 ** (0.041) | 0.103 *** (0.042) | ||

| Disease prevention and risk monitoring | −0.004 (0.042) | 0.028 (0.042) | ||

| Assisting drug research | 0.210 *** (0.045) | 0.230 *** (0.046) | ||

| Demographic factors | ||||

| Female | −0.176 ** (0.080) | −0.134 ** (0.080) | ||

| Age | 0.323 *** (0.046) | 0.458 *** (0.048) | ||

| Education level | 0.144 *** (0.038) | 0.107 *** (0.038) | ||

| Urban | −0.169 (0.102) | −0.236 (0.103) | ||

| Average annual household income | −0.066 * (0.038) | −0.133 *** (0.037) | ||

| Health status information | ||||

| Current health status better | 0.442 *** (0.104) | 0.423 *** (0.105) | ||

| Feeling unwell for less than 15 days | 0.288 *** (0.100) | 0.408 *** (0.101) | ||

| N | 2488 | 2488 | 2488 | 2488 |

| McFadden R-squared | 0.092 | 0.109 | 0.124 | 0.141 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Q.; Chen, B.; Zhu, J. Insights from COVID-19: Reflecting on the Promotion of Long-Term Health Policies in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042889

Wu Q, Chen B, Zhu J. Insights from COVID-19: Reflecting on the Promotion of Long-Term Health Policies in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):2889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042889

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Qi, Beian Chen, and Jianping Zhu. 2023. "Insights from COVID-19: Reflecting on the Promotion of Long-Term Health Policies in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 2889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042889

APA StyleWu, Q., Chen, B., & Zhu, J. (2023). Insights from COVID-19: Reflecting on the Promotion of Long-Term Health Policies in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042889