Access to Maternity Protection and Potential Implications for Breastfeeding Practices of Domestic Workers in the Western Cape of South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

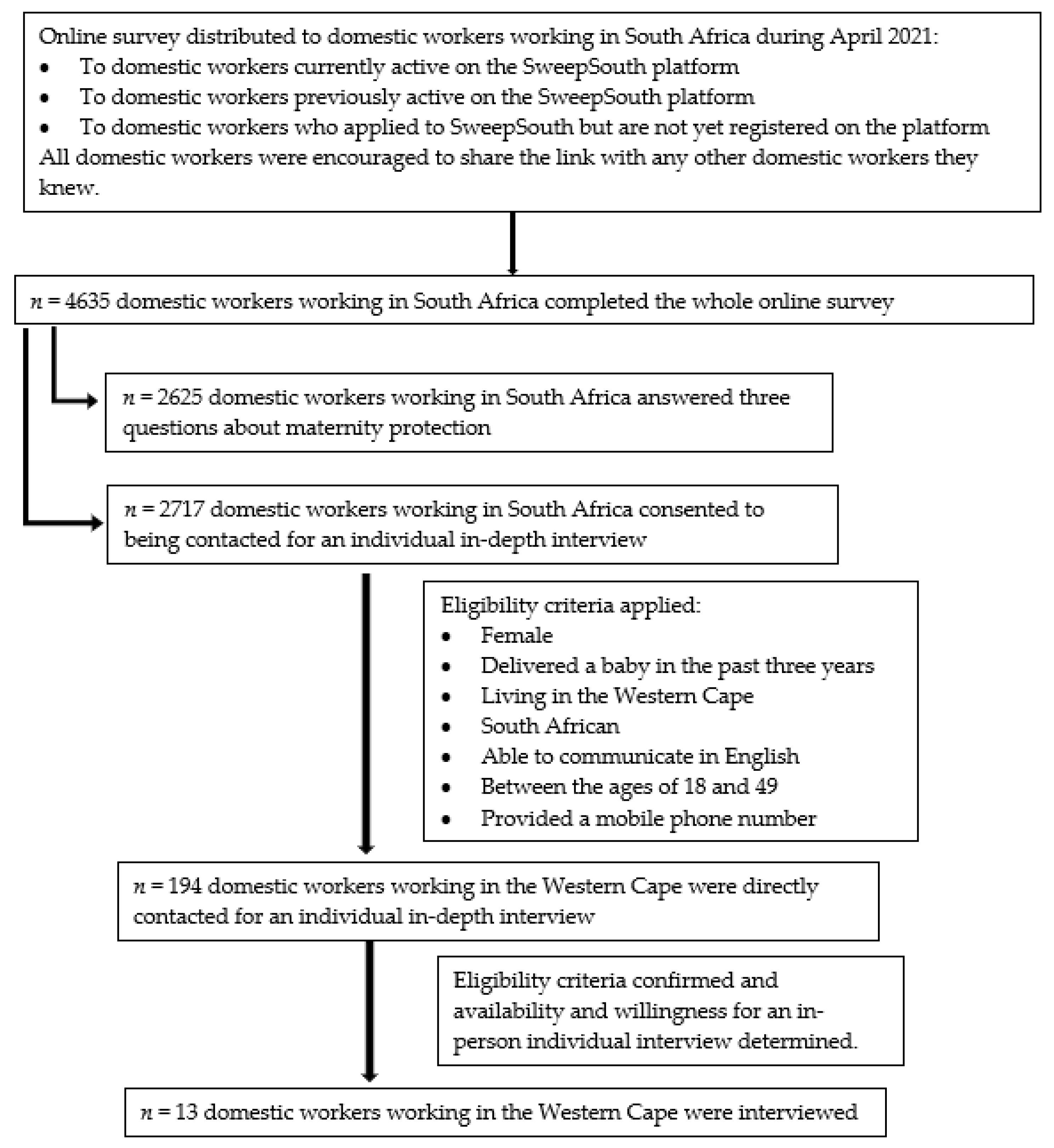

2.2. Participant Sampling and Selection

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethics Approval

3. Results

3.1. Domestic Workers’ Perceptions of Maternity-Protection Entitlements

3.2. Domestic Workers’ Access to the Different Components of Maternity Protection

3.2.1. Socio-demographic Characteristics of Domestic Workers Included in the Sample for IDIs

3.2.2. Health Protection at the Workplace for Domestic Workers Is Employer-Dependent

“Washing the windows. Clean the windows. I couldn’t climb up. Or to clean all the cupboards. Or carry some heavy stuff. I couldn’t. They were very, like understanding. I didn’t do all of those things. I think they understand, because I was pregnant. I didn’t even have to tell them, that I can’t do this, so sometimes they will just know. Just do this, just do the basics, then you go, because maybe you are tired. So, I think they were very supportive.”(Domestic worker, DW2, worker for private clients)

“Like moving the things. The hard things, like the fridges and stuff. I, I told her that I’m no longer going to, but she’s the one, she was straight. She’s the one who told me, you must not move anything now that you’re pregnant, because it’s gonna hurt your baby. So, whenever that needs to be moved, she asked someone else to do that.”(DW8, worker for a private client)

“Sometimes, if you work here in [two Cape Town suburbs], yoh! People from there. No, they, even if they see that you’re, like you’re struggling, they want to scrub to, kneel down. So, it’s very difficult.”(DW11, platform worker)

“Like the one I was last, I’m a Caesarean person. Like, I have to take it with some small break. To go there, in there, and put my bandage because my operation wasn’t, not yet healed… It was sore. I still had to work.”(DW12, platform worker)

“It was hard, hard to work while I’m pregnant because I told them, I asked, maternity leave. They said, like the customer, the client, I asked to take leave. They said no. You can’t because we’re gonna need someone here. I have to work till my due date. Then I woke up at one in the morning on my due date. I called the bosses. They came down. They took me to hospital. Then I left for hospital, when I’m done everything, I gave birth. I go. I went home. I didn’t get paid.”(DW12, platform worker)

Access to Health Care for Domestic Workers during the Antenatal and Postnatal Periods Necessitates Unpaid Leave

“If I will go to the clinic, I must take a day off.”(DW1, worker for a private client)

“No, she didn’t say anything about that. But she told me, she told me if I need to go see the doctor, I must tell her, if maybe, that day that I should come to work, is the same day that I should go to the clinic, I just have to tell her, then we’ll redo the schedule.”(DW8, worker for a private client)

“Yes, I was able but if I go to the clinic the money is cut. Ja, because at the clinic, er, it’s busy in our clinic, so we spend almost a day, almost the whole day. Ja, so there’s no use to go to work maybe around three or two.”(DW13, worker for private clients and platform worker)

3.2.3. Some Domestic Workers Experience Discrimination due to Pregnancy and Childbirth

“They say there at work [online platform], if you’re pregnant, they’re going to deactivate you. Then you must tell them, when you come back, they’re gonna interview again.”(DW3, platform worker)

“No, afterwards she said, I must abort the baby. I said no. Because she knows me, a long time ago, I got three children already. The first born was one. Then I got a second child. They are twenty-one now. The oldest one is twenty-five now. The second ones are twins. So, she said to me, how could you have another baby again? You know? So, I said, no, I’m not gonna kill my baby. I’m gonna have my baby, and then I’m gonna close it [perform a sterilisation procedure]. It’s a mistake. I know it’s a mistake, but I’m not gonna abort.”(DW9, worker for a private client)

“So after she found out, I saw the changes in her like she’s no longer the same, I don’t know. Not at all alright. I’m not supposed to be pregnant while I’m working.”(DW13, worker for private clients and platform worker)

3.2.4. Many Domestic Workers Experience Job Insecurity Due to Pregnancy and Childbirth

“But to have a baby, you must say you’re gonna lose this job. It’s not easy to have a baby there at online platform.”(DW3, platform worker)

“Because, some I did lose because there are people who say, no, she’s pregnant. Now we can’t work with her. So, I lose some, four jobs that I lose. Then I started the new ones.”(DW4, platform worker)

“If I was on maternity leave for three months, maybe she [the employer] will book someone else and then she will say: ah, this one is good. More than me. And then they will hire them.”(DW1, worker for a private client)

“Yes, when I was pregnant, I was worried. I thought they’re gonna put another one. They’re gonna replace someone in my place.”(DW12, platform worker)

“Because when I was still pregnant… I felt like I can’t handle the job. I said to her—no ma’m, I need to rest, because I feel the pain if I work hard. Then I need to rest and then I will come back when I deliver. And then she said fine. We didn’t fight. We didn’t do anything. She said it’s fine. I say to her, can I bring someone to step in for me while I’m in maternity? She said, no, no, no, no. I will wait for you. The minute you feel okay, you can just phone me and then you come back. So we didn’t fight. We didn’t do anything… I feel like that lady betrayed me. She was supposed to pay me. Ja. If she fires me, she’s supposed to pay me. And she knows that thing’s wrong”(DW9, worker for a private client)

3.2.5. Difficulties for Domestic Workers to Access Paid Maternity Leave

Domestic Workers Are Unable to Access Cash Payments While on Maternity Leave despite Legal Eligibility to Social Insurance in SA

“They [online platform] don’t want us to have a UIF. I don’t know, they don’t explain to us why they don’t have a UIF. We don’t have leave, if you’re on leave, you’re unpaid. I don’t know why they do this.”(DW4, platform worker)

“They are not deducting, the UIF money. You see? Now I’m stranded, I’m having a baby, there was no maternity leave benefit. No provident fund, no nothing. If you don’t work, you don’t get paid. So, I’m gonna find another job or else I will go back to security…. I will go back to my security job, where there are, benefits, like UIF and provident fund.”(DW1, worker for a private client)

“I heard about the UIF, but I don’t know.”(DW12, platform worker)

“I’m not sure. How does it go? How do you get registered and stuff like this, so I’m not, educated on how to do that…. I don’t know how much are they going to take it from my money to, to pay the UIF? Or they are going to contribute? I am not sure. I am not totally sure about that.”(DW2, worker for private clients)

“I think sometimes you lose your job… sometimes you are pregnant and then you have to receive some money to feed your baby.”(DW11, platform worker)

“It’s because when the time that, when I’m sitting down, like the time I was on maternity leave, I was supposed to get money. But I didn’t get money because I wasn’t working. So, I think it’s very important to get UIF. So that when you’ve got a problem, you can claim UIF, if you don’t have the money.”(DW8, worker for a private client)

“And they always answer us and say, we are not employers. We are the platform. So, we just keep quiet. We don’t know where to go. And we are scared to be fired, while we still need a job.”(DW11, platform worker)

Unpaid Maternity Leave Is the Only Leave Option for Domestic Workers but Is Unaffordable and Therefore Inaccessible

“No, they [manager at online platform] just say I must take, if you have a maternity leave, no work, no pay.”(DW3, platform worker)

“I did take off… fourteen days. I didn’t get paid. Because there’s no food on the table, so I got up and go and work.”(DW3, platform worker)

“I didn’t take maternity leave… Because they don’t have anything to contribute to me. So, I must go to work.”(DW4, platform worker)

“I don’t think, I think we have the maternity leave, but I don’t think so. They deactivate you on the platform. That’s just only thing I know. You don’t get nothing.”(DW10, platform worker)

“I don’t mind for maternity leave, but for the UIF. I think it, every worker, it’s necessary to have UIF.”(DW4, platform worker)

Inaccessibility to Social Insurance Results in Dependence on Social Assistance, Which Also Has Challenges

“You must wait for birth certificate, clinic card, and then there by the hospital, they don’t send the social workers to do grants for you. They just send someone from home affairs, to do the certificate, which is right. But for SASSA [South African Social Security Agency, responsible for administration of the Child Support Grant], there’s not someone there at the hospital asking do you need a form to apply for the grant for SASSA. You must wake up early in the morning. Four o’ clock you must be out of your house... Five o’ clock you take queue. There are many people there. So maybe you’re gonna sit outside with this small child… If your child is hungry, they’re gonna attend you at one o’ clock. It’s the first day you apply. Then you must wake up again. Four o’ clock to get this child grant again. They can attend you one o’ clock again. To bring back the forms. It takes a long time and there in [an informal settlement], we don’t have SASSA. We must take a taxi to Cape Town. It’s very difficult for us as a domestic worker.”(DW3, platform worker)

“So, I have to ask my mother-in-law to make the grant there by Eastern Cape because it’s very easy to make the grant in Eastern Cape… She transfers the money to me. I go there to give my, mother the certificate and the card and I came back. And my mother did everything there… Yoh, a lot of times and I get the date there by [suburb in the Western Cape] and I was unlucky that day because there was a noise and they said; no, you must go to [different area in the Western Cape] and other areas… So, I was in need. So that’s why I asked my mother to.”(DW11, platform worker)

3.2.6. Domestic Workers Are Not Familiar with the Entitlement to Breastfeeding Breaks upon Return to Work

“It’s the first time I hear about it.”(DW2, worker for private clients)

“I only express when I’m at home”(DW5, worker for private clients and platform worker)

“How do they do that? Because maybe I’m working in town and my baby is at the crèche, maybe with my sister at my house. So, if I had a break, I have to go home. Or what?”(DW8, worker for a private client)

“To get the knowledge about the breaks, yes, and breaks to express the milk, yes. I think most people need to know about that. Like because I didn’t know either.”(DW13, worker for private clients and platform worker)

“I think the, what you’re talking now about, that’s of the breastmilk breaks? I think that if people knew about it, I think they will just take their break and try and do the, express. And if they know, if they are guaranteed that their jobs are not at stake, maybe.”(DW2, worker for private clients)

“She’s [the employer] the one who said, I must come to work with him. She gives me time to breastfeed him.”(DW1, worker for a private client)

3.2.7. Challenges with Storing Expressed Breastmilk at Work

“Like the breastmilk is not, like when it’s in a bottle, it’s not, like a nice colour, you know? They can’t put it in the bag too because during the day, the milk is gonna go sour.”(DW9, worker for a private client)

“I think it will depend on the belief of that someone. Because some, they don’t have the information. Some, they don’t like even the breastmilk… Even my husband, like the first time I put it in the fridge, they laughed and; please don’t use the, like the container. I’m going to use it again.”(DW11, platform worker)

“There’s two fridges in the garage, where they put some things. So, I, if I go to her again, I’ll talk to her and then I’ll leave it [expressed breastmilk] there. I don’t think she can refuse.”(DW6, worker for private clients and platform worker)

3.2.8. Domestic Workers Struggle to Access Childcare on Return to Work

“But in the online platform they tell us in the booking, you are not allowed for the baby. If you grab your booking, don’t go to the client’s house with the baby.”(DW3, platform worker)

“There’s nothing, which I’m benefitting. It’s just a loss… You’re just working only for the transport…. Because when you count that money, a day I work for one twenty or one forty [ZAR = USD 7 or 8]. It can’t reach to where I want it to go, but at least, I don’t sleep hungrier, at least, but it can’t take me anywhere…. Like the hours? The money is small.”(DW7, platform worker)

“So the crèches in town, in our location is, the money. It’s cheaper in the location. But we have to leave him the whole day in the location [i.e., township or informal settlement].”(DW13, worker for private clients and platform worker)

3.2.9. Domestic Workers Provided Suggestions for Improving Access to Maternity Protection

“I did hear that there’s some people that get in the houses and ask for the one who have a domestic worker. They ask—but, even one day I didn’t see them at my work. Because I was thinking maybe why they don’t, why they [Department of Employment and Labour] don’t come here and ask for it, so that I can be registered.”(DW6, worker for private clients and platform worker)

“If the employers, they can say; you are welcome with your, child. You can take the child with you if you’re going to work. Because we do the house chores with the babies. We can put the baby on our backs and still work, even at home. So, we can do that at the employer’s house. So, they can take the babies with them if they don’t have the money to take them to the crèche or they are still too young to go to the crèche”(DW8, worker for a private client)

“I don’t think you can work nicely when the baby is around.”(DW9, worker for a private client)

4. Discussion

4.1. Domestic Workers in SA Are Unaware of Their Maternity Protection Entitlements

4.2. Some Components of Maternity Protection Are Available to Domestic Workers in SA, but Are Inaccessible

4.2.1. Challenges in the Implementation of Social Insurance in SA

4.2.2. Limitations to the Enforcement of Maternity-Protection Legislation in SA

4.2.3. Unclear Guidance on Certain Components of Maternity Protection

4.2.4. Breastfeeding Breaks and Childcare Components of Maternity Protection Should Be Accessible to Domestic Workers

4.3. International Accountability for Maternity Protection in SA Should Be Ensured

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Maternity Protection Resource Package. Module 1: Maternity Protection at Work: What is it? Geneva. 2012. Available online: https://mprp.itcilo.org/allegati/en/m1.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Maternity Protection Recommendation No. 183. Geneva. 2000. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:55:0::NO::P55_TYPE,P55_LANG,P55_DOCUMENT,P55_NODE:REV,en,C183,/Document (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Maternity Protection Recommendation No. 191. Geneva. 2000. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:12100:::NO:12100:P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312529 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Rollins, N.C.; Bhandari, N.; Hajeebhoy, N.; Horton, S.; Lutter, C.K.; Martines, J.C.; Piwoz, E.G.; Richter, L.M.; Victora, C.G. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet 2016, 387, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Department of Health (NDoH), Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), ICF. South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Pretoria, South Africa and Rockville, Maryland, USA. 2019. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR337/FR337.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Nutrition Targets 2025 Policy Brief Series. Geneva. 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-14.2 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- WHO/UNICEF. WHO/UNICEF Discussion Paper: The Extension of the 2025 Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition Targets to 2030. New York: UNICEF. 2019. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/who-unicef-discussion-paper-nutrition-targets/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Chen, M.A. The Informal Economy: Definitions, Theories and Policies. 2012. Available online: https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/Chen_WIEGO_WP1.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Making the Right to Social Security a Reality for Domestic Workers: A Global Review of Policy Trends, Statistics and Extension Strategies. Geneva: ILO. 2022. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_848280/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Non-Standard Employment Around the World: Understanding Challenges, Shaping Prospects. Geneva. 2016. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_534326/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- IZWI Domestic Workers Alliance, Solidarity Center. The Persistence of Private Power: Sacrificing Rights for Wages. A Qualitative Survey of Human Rights Violations against Live-In Domestic Workers in South Africa. 2021. Available online: https://www.solidaritycenter.org/publication/the-persistence-of-private-power-sacrificing-rights-for-wages-south-africa/ (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- De Stefano, V.; Durri, I.; Stylogiannis, C.; Wouters, M. Platform work and the employment relationship. International Labour Organization Working Paper. Geneva. 2021. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/working-papers/WCMS_777866/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Gig Work on Digital Platforms. 2020. Available online: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00WHJ7.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Pereira-Kotze, C.; Malherbe, K.; Faber, M.; Doherty, T.; Cooper, D. Legislation and Policies for the Right to Maternity Protection in South Africa: A Fragmented State of Affairs. J. Hum. Lact. 2022, 38, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira-Kotze, C.; Doherty, T.; Faber, M. Maternity protection for female non-standard workers in South Africa: The case of domestic workers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO), International Labour Organization (ILO). Statistical Brief No. 32. Domestic Workers in the World: A Statistical Profile. 2022. Available online: https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/publications/file/WIEGO_Statistical_Brief_N32_DWs%20in%20the%20World.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Statistics South Africa (Stats SA). Quarterly Labour Force Survey. Quarter 2: 2022. Pretoria. 2022. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02112ndQuarter2022.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Navarro-Rosenblatt, D.; Garmendia, M.-L. Maternity Leave and Its Impact on Breastfeeding: A Review of the Literature. Breastfeed. Med. 2018, 13, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, Y.; Nandi, A.; Heymann, J. Does extending the duration of legislated paid maternity leave improve breastfeeding practices? Evidence from 38 low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e001032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwood, C.; Haskins, L.; Alfers, L.; Masango-Muzindutsi, Z.; Dobson, R.; Rollins, N. A descriptive study to explore working conditions and childcare practices among informal women workers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Identifying opportunities to support childcare for mothers in informal work. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhan, G.; Surie, A.; Horwood, C.; Dobson, R.; Alfers, L.; Portela, A.; Rollins, N. Informal work and maternal and child health: A blind spot in public health and research. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.D.; França, G.V.A.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Snkar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016, 387, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics South Africa (Stats SA). Nearly Half of SA Women are Out of the Labour Force in Q2:2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=15668 (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Statistics South Africa (Stats SA). Statistical Release P0302: Mid-Year Population Estimates 2022. Pretoria. 2022. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022022.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Western Cape Government. Socio-Economic Profile (SEP): City of Cape Town. 2016. Available online: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/assets/departments/treasury/Documents/Socio-economic-profiles/2016/City-of-Cape-Town/city_of_cape_town_2016_socio-economic_profile_sep-lg.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Xe Currency Converter. Available online: https://www.xe.com/currencyconverter/convert/?Amount=1&From=ZAR&To=USD (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Vaismoradi, M.; Snelgrove, S. Theme in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. Forum Qual. Soz. 2019, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Western Cape Government. SASSA Child Support Grant. Cape Town. 2022. Available online: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/service/sassa-child-support-grant#:~:text=What's%20the%20grant%20amount%3F,point%20of%20a%20Regional%20Office (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Heymann, J.; Raub, A.; Earle, A. Breastfeeding policy: A globally comparative analysis. Bull. World Health Organ. 2013, 91, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alb, C.H.; Theall, K.; Jacobs, M.B.; Bales, A. Awareness of United States’ Law for Nursing Mothers among Employers in New Orleans, Louisiana. Women Health Issues 2017, 27, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A.K.; Johnson, E.; Motoyasu, N.; Bignell, W.E. Awareness of Breastfeeding Laws and Provisions of Students and Employees of Institutions of Higher Learning in Georgia. J. Hum. Lact. 2019, 35, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Cashin, J.; Tran, H.T.T.; Vu, D.H.; Nandi, A.; Phan, M.T.; Van, N.D.C.; Weissman, A.; Pham, T.N.; Nguyen, B.V.; et al. Awareness, Perceptions, Gaps, and Uptake of Maternity Protection among Formally Employed Women in Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (SERI), IZWI Domestic Workers Alliance. Employing a Domestic Worker: A Legal and Practical Guide. 2021. Available online: https://seri-sa.org/images/SERI_Employers_Rights_Guide_Final.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Jahan, R.; Zou, P.; Huang, Y.; Jibb, L. Impact of MomConnect Program in South Africa: A Narrative Review. Online J. Nurs. Inform. 2020, 24. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Maternity Protection Resource Package. Module 3: Maternity Protection at work: Why is It Important? 2012. Available online: https://mprp.itcilo.org/allegati/en/m3.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- International Labour Office (ILO). Domestic Work Policy Brief 6: “Meeting the Needs of My Family Too”—Maternity Protection and Work-Family Measures for Domestic Workers. Geneva. 2013. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_216940.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Coverage of Domestic Workers by Key Working Conditions Laws. Geneva. 2013. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_157509.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Pereira-Kotze, C.; Faber, M.; Doherty, T. Knowledge, understanding and perceptions of key stakeholders on the maternity protection available and accessible to female domestic workers in South Africa. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2022, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes University. Domestic Workers UIF/COIDA Advocacy Workshop: 19–21 February 2022. Available online: https://www.ru.ac.za/nalsu/latestnews/domesticworkersuifcoidaadvocacyworkshop.html (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). World Social Protection Report 2017–2019: Universal Social Protection to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva. 2017. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_604882/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- National Economic and Development Authority. Philippine Development Plan 2017–2022. Paisig City. 2017. Available online: https://pdp.neda.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/20210218-Pre-publication-copy-Updated-Philippine-Development-Plan-2017-2022.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- National Department of Labour. Basic Conditions of Employment Act No. 75 of 1997. Pretoria. 1997. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a75-97.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- SweepSouth. Domestic Worker Survey: South Africa & Kenya. National Department of Labour (NDoL). 2022. Available online: https://blog.sweepsouth.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Fifth-Annual-Domestic-Workers-Report.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Code of Good Practice on the Protection of Employees During Pregnancy and After the Birth of a Child. Pretoria. 1998. Available online: https://www.labourguide.co.za/workshop/1248-14-code-of-good-practice-on-the-protection-of-employees-during-pregnancy-and-after-the-birth-of-a-child/file (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Bresnahan, M.; Zhuang, J.; Anderson, J.; Zhu, Y.; Nelson, J.; Yan, X. The “pumpgate” incident: Stigma against lactating mothers in the U.S. workplace. Women Health 2018, 58, 451–465. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1080/03630242.2017.1306608 (accessed on 12 January 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Maternity Protection Resource Package. Module 11: Beyond Maternity and Back to Work: Coping with Childcare. Geneva. 2012. Available online: https://mprp.itcilo.org/allegati/en/m11.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Alfers, L. “Our Children Do Not Get the Attention They Deserve”: A Synthesis of Research Findings on Women Informal Workers and Child Care from Six Membership-Based Organizations. Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO). 2016. Available online: https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/Alfers-Child-Care-Initiative-Full-Report.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Ratifications of C183— Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183). 2022. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:11300:0::NO:11300:P11300_INSTRUMENT_ID:312328 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

| Component of Maternity Protection | Provisions in South African Policy and Legislation |

|---|---|

| Maternity leave | All workers entitled to four consecutive calendar months of unpaid maternity leave in accordance with the Basic Conditions of Employment Act. |

| Cash benefits | Women working at least 24 h per month are entitled to social insurance, whereby employers and employees make monthly contributions to the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) and women can claim two-thirds of their earnings (up to a maximum threshold) as maternity benefits. This is mandated by the Unemployment Insurance Act. |

| Medical benefits | In SA, access to healthcare is available to all, including pregnant and breastfeeding women, through public healthcare services guaranteed by the Constitution. |

| Health protection | A Code of Good Practice on the Protection of Employees During Pregnancy and After the Birth of a Child contains guidance on health protection for pregnant and breastfeeding women. |

| Employment protection | All pregnant women in SA are entitled to job security, since dismissal related to pregnancy is prohibited by the Labour Relations Act. |

| Non-discrimination | All women in SA are protected by non-discrimination due to pregnancy through the Constitution. |

| Breastfeeding breaks | The Code of Good Practice on the Protection of Employees During Pregnancy and After the Birth of a Child recommends twice daily breastfeeding breaks of 30 min for all working women until their child is six months old, but this is not legislated. |

| Childcare support | There is no legislation on childcare support for working women in SA. |

| Characteristic | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 2537 | 96.7 |

| Male | 82 | 3.1 | |

| Other/prefer not to say | 6 | 0.2 | |

| Age | Average: 35.5 years; range of 19–62 years | ||

| Nationality | Zimbabwe | 1514 | 57.7 |

| South Africa | 1031 | 39.3 | |

| Malawi | 32 | 1.2 | |

| Lesotho | 21 | 0.8 | |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 20 | 0.8 | |

| Other a | 7 | 0.3 | |

| Province of work | Gauteng | 1453 | 55.4 |

| Western Cape | 1006 | 38.3 | |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 148 | 5.6 | |

| Other b | 18 | 0.7 | |

| Number of children | None | 99 | 3.8 |

| One | 553 | 21.1 | |

| Two | 1022 | 38.9 | |

| Three | 659 | 25.1 | |

| Four | 224 | 8.5 | |

| Five | 53 | 2 | |

| Six or more | 15 | 0.6 | |

| Earnings from domestic work (per month) | Less than R1500 c | 542 | 20.7 |

| ZAR 1501–2000 | 371 | 14.1 | |

| ZAR 2001–3000 | 828 | 31.5 | |

| ZAR 3001–4000 | 536 | 20.4 | |

| ZAR 4001–5000 | 239 | 9.1 | |

| ZAR 5001–6000 | 76 | 2.9 | |

| ZAR 6001–7000 | 26 | 1 | |

| More than ZAR 7000 | 7 | 0.3 | |

| Registered for the UIF | Yes | 203 | 7.7 |

| No | 2124 | 80.9 | |

| Do not know | 298 | 11.4 | |

| Do you think that a domestic worker who is pregnant at the moment is allowed to receive any of the following benefits? (Choose all that apply.) | Yes | % |

|---|---|---|

| Paid time off work during her pregnancy to attend pregnancy (antenatal) clinic visits. | 1762 | 67.1 |

| Unpaid time off work during her pregnancy to attend pregnancy (antenatal) clinic visits. | 149 | 5.7 |

| Have her employer make changes to the tasks she has to carry out during her work so as not to cause any harm to her or her baby during her pregnancy (for example, not having to lift heavy objects or bend over towards the end of her pregnancy). | 1181 | 45.0 |

| She should not be allowed to lose her job just because she is pregnant or will be having a baby. | 1359 | 51.8 |

| She should not be discriminated against because she is pregnant or will be having a baby (for example, her pay should not be reduced because she is pregnant; if starting with a new employer, the employer should not state that she cannot fall pregnant). | 1224 | 46.6 |

| Do not know. | 140 | 5.3 |

| If you, or a domestic worker in a similar position to you, were to fall pregnant and have a baby, which maternity benefits do you think you or she would be able to receive? (Select only ONE option.) | ||

| No maternity leave, or less than 6 weeks leave (after the baby is born). | 100 | 3.8 |

| Some maternity leave (more than 6 weeks and less than 4 months of leave after the baby is born). | 546 | 20.8 |

| Four months of unpaid maternity leave. | 52 | 2.0 |

| Four months of partially paid maternity leave. | 525 | 20.0 |

| Four months of maternity leave and can claim from the UIF. | 563 | 21.5 |

| Four months of full paid maternity leave (organised by the employer). | 687 | 26.2 |

| Do not know what is allowed. | 152 | 5.8 |

| Do you think that when a domestic worker returns to work after maternity leave she is allowed to: (Choose all that apply.) | ||

| Take paid time off work to attend baby (postnatal) clinic visits? | 1579 | 60.2 |

| Take unpaid time off work to attend baby (postnatal) clinic visits? | 411 | 15.7 |

| Take daily breastfeeding breaks (at least one break during the working day to either express breastmilk or breastfeed the baby)? | 479 | 18.3 |

| Bring her baby to work with her? | 177 | 6.7 |

| None of the above. | 278 | 10.6 |

| Do not know. | 245 | 9.3 |

| Components of Maternity Protection | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| Health protection at the workplace | ● Health protection at the workplace for domestic workers is employer-dependent |

| Medical benefits while on maternity leave | ● Access to health care for domestic workers during the antenatal and postnatal periods necessitates unpaid leave |

| Non-discrimination and job security for pregnant and breastfeeding women | ● Some domestic workers experience discrimination due to pregnancy and childbirth ● Many domestic workers experience job insecurity due to pregnancy and childbirth |

| Cash benefits while on maternity leave | ● Domestic workers are unable to access cash payments while on maternity leave despite legal eligibility to social insurance in SA ● Inaccessibility to social insurance results in dependence on social assistance, which also has challenges |

| A period of maternity leave | ● Unpaid maternity leave is available to domestic workers but is unaffordable and therefore inaccessible |

| Breastfeeding (or expressing) breaks on return to work | ● Domestic workers are not familiar with the entitlement to breastfeeding breaks upon return to work ● Challenges with storing expressed breastmilk at work |

| Support to access childcare | ● Domestic workers struggle to access childcare on return to work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereira-Kotze, C.; Faber, M.; Kannemeyer, L.; Doherty, T. Access to Maternity Protection and Potential Implications for Breastfeeding Practices of Domestic Workers in the Western Cape of South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2796. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042796

Pereira-Kotze C, Faber M, Kannemeyer L, Doherty T. Access to Maternity Protection and Potential Implications for Breastfeeding Practices of Domestic Workers in the Western Cape of South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):2796. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042796

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira-Kotze, Catherine, Mieke Faber, Luke Kannemeyer, and Tanya Doherty. 2023. "Access to Maternity Protection and Potential Implications for Breastfeeding Practices of Domestic Workers in the Western Cape of South Africa" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 2796. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042796

APA StylePereira-Kotze, C., Faber, M., Kannemeyer, L., & Doherty, T. (2023). Access to Maternity Protection and Potential Implications for Breastfeeding Practices of Domestic Workers in the Western Cape of South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2796. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042796