Assessing Quality of Life in First- and Second-Generation Immigrant Children and Adolescents; Highlights from the DIATROFI Food Aid and Healthy Nutrition Promotion Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

2.2. Bioethics

2.3. Baseline Assessment

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Students and Their Families

2.3.2. Definition of Student’s Immigration Status

2.3.3. Students’ HRQoL

2.4. Statistical Analysis

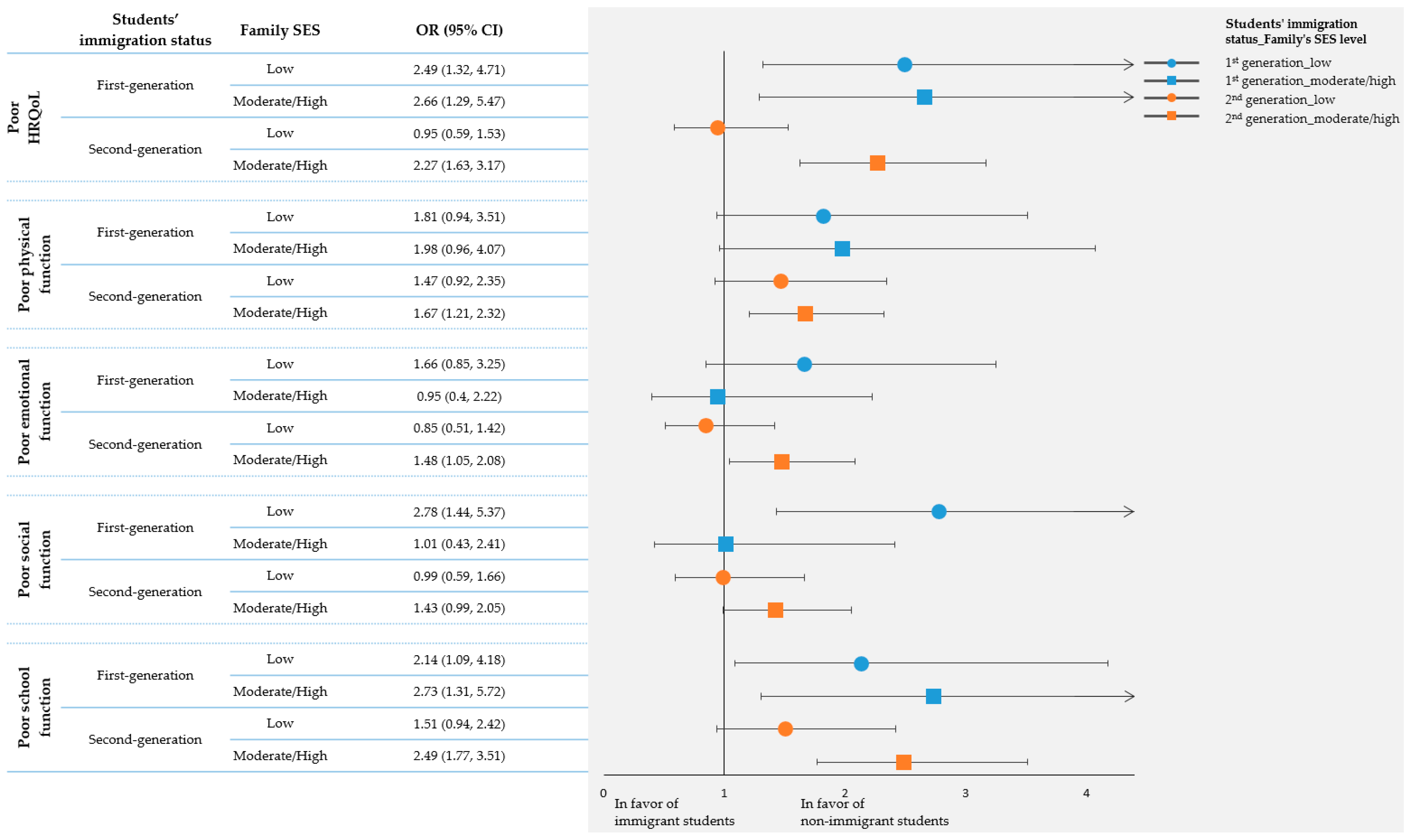

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ayalew, B.; Dawson-Hahn, E.; Cholera, R.; Falusi, O.; Haro, T.M.; Montoya-Williams, D.; Linton, J.M. The Health of Children in Immigrant Families: Key Drivers and Research Gaps Through an Equity Lens. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 21, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, R.; Li, C.; Qi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Birth and Health Outcomes of Children Migrating With Parents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 810150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crookes, D.M.; Stanhope, K.K.; Kim, Y.J.; Lummus, E.; Suglia, S.F. Federal, State, and Local Immigrant-Related Policies and Child Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 9, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrova, R.; Chasiotis, A.; van de Vijver, F. Adjustment Outcomes of Immigrant Children and Youth in Europe: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. Psychol. 2016, 21, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, R.; Liamputtong, P.; Arora, A. Prevalence, Determinants, and Effects of Food Insecurity among Middle Eastern and North African Migrants and Refugees in High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation: A Conceptual Overview. In Acculturation and Parent-Child Relationships; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-415-96358-9. [Google Scholar]

- Motti-Stefanidi, F. Resilience among Immigrant Youth: The Role of Culture, Development and Acculturation. Dev. Rev. 2018, 50, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilario, C.T.; Oliffe, J.L.; Wong, J.P.-H.; Browne, A.J.; Johnson, J.L. Migration and Young People’s Mental Health in Canada: A Scoping Review. J. Ment. Health 2015, 24, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggli, Z.; Mertens, T.; -Sá, S.; Amado, R.; Teixeira, A.L.; Vaz, D.; O. Martins, M.R. Migration as a Determinant in the Development of Children Emotional and Behavior Problems: A Quantitative Study for Lisbon Region, Portugal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottinger, A.M. Children’s Experience of Loss by Parental Migration in Inner-City Jamaica. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2005, 75, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Policy Brief No. 133: Migration Trends and Families. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/un-desa-policy-brief-no-133-migration-trends-and-families/ (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Eurostat First and Second-Generation Immigrants—Statistics on Main Characteristics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=First_and_second-generation_immigrants_-_statistics_on_main_characteristics (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Loi, S.; Pitkänen, J.; Moustgaard, H.; Myrskylä, M.; Martikainen, P. Health of Immigrant Children: The Role of Immigrant Generation, Exogamous Family Setting, and Family Material and Social Resources. Demography 2021, 58, 1655–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotsika, V.; Vlassopoulos, M.; Kokkevi, A.; Fragkaki, I.; Anagnostopoulos, D.C.; Lazaratou, H.; Ginieri-Coccossis, M. Comparing Immigrant Children with Native Greek in Self-Reported-Quality of Life. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. 2016, 27, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Villalonga-Olives, E.; von Steinbüchel, N.; Witte, C.; Kasten, E.; Kawachi, I.; Kiese-Himmel, C. Health Related Quality of Life of Immigrant Children: Towards a New Pattern in Germany? BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J. Comparative Study of Life Quality Between Migrant Children and Local Students in Small and Medium-Sized Cities in China. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2018, 35, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudry, A.; Wimer, C. Poverty Is Not Just an Indicator: The Relationship Between Income, Poverty, and Child Well-Being. Acad. Pediatr. 2016, 16, S23–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yannakoulia, M.; Lykou, A.; Kastorini, C.M.; Saranti Papasaranti, E.; Petralias, A.; Veloudaki, A.; Linos, A. DIATROFI Program Research Team Socio-Economic and Lifestyle Parameters Associated with Diet Quality of Children and Adolescents Using Classification and Regression Tree Analysis: The DIATROFI Study. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, W.; Torsheim, T.; Currie, C.; Zambon, A. The Family Affluence Scale as a Measure of National Wealth: Validation of an Adolescent Self-Report Measure. Soc. Indic. Res. 2006, 78, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkoltsiou, K.; Papaevangelou, V.; Konstandopoulos, A. Pilot Testing of the Greek Version of the PedsQL 4.0 Instrument. Patient Rep. Outcomes Newsl. 2006, 37, 15. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Migration and Migrant Population Statistics; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2022.

- European Commission Population on 1 January by Age and Sex; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2022.

- UNICEF Refugee and Migrant Children. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/greece/en/refugee-and-migrant-children (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- European Commission Migrant Integration Statistics—At Risk of Poverty and Social Exclusion; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2021.

- European Commission 1 in 4 Children in the EU at Risk of Poverty or Social Exclusion; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2021.

- Kroening, A.L.H.; Dawson-Hahn, E. Health Considerations for Immigrant and Refugee Children. Adv. Pediatr. 2019, 66, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang, Z.M.; Sigouin, J.; Flenon, A.; Gagnon, A. Are Immigrants Healthier than Native-Born Canadians? A Systematic Review of the Healthy Immigrant Effect in Canada. Ethn. Health 2017, 22, 209–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das-Munshi, J.; Leavey, G.; Stansfeld, S.A.; Prince, M.J. Migration, Social Mobility and Common Mental Disorders: Critical Review of the Literature and Meta-Analysis. Ethn. Health 2012, 17, 17–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, S.; Tam, W.; Ho, C.; Tran, B.; Nguyen, L.; McIntyre, R.; Ho, R. Prevalence of Depression among Migrants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, P.P. Intergenerational Cultural Conflict, Mental Health, and Educational Outcomes among Asian and Latino/a Americans: Qualitative and Meta-Analytic Review. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 404–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linton, J.M.; Choi, R.; Mendoza, F. Caring for Children in Immigrant Families. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2016, 63, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiri, S. Global Prevalence of Anxiety and PTSD in Immigrants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychiatrie 2022, 36, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charbonneau, S.; deLeyer-Tiarks, J.; Caterino, L.C.; Bray, M. A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Interventions for Student Refugees, Migrants, and Immigrants. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2022, 50, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowden, J.D.; Kreisler, K. Development in Children of Immigrant Families. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2016, 63, 775–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgna, C.; Contini, D. Migrant Achievement Penalties in Western Europe: Do Educational Systems Matter? Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 30, 670–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.M.; Pong, S.; Mori, I.; Chow, B.W.-Y. Immigrant Students’ Emotional and Cognitive Engagement at School: A Multilevel Analysis of Students in 41 Countries. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 1409–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; White, M.J. Education Outcomes of Immigrant Youth: The Role of Parental Engagement. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2017, 674, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebano, A.; Hamed, S.; Bradby, H.; Gil-Salmerón, A.; Durá-Ferrandis, E.; Garcés-Ferrer, J.; Azzedine, F.; Riza, E.; Karnaki, P.; Zota, D.; et al. Migrants’ and Refugees’ Health Status and Healthcare in Europe: A Scoping Literature Review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commision Action Plan on the Integration and Inclusion. Available online: https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/migration-and-asylum/legal-migration-and-integration/integration/action-plan-integration-and-inclusion_en (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Thompson, J.; Fairbrother, H.; Spencer, G.; Curtis, P.; Fouche, C.; Hoare, K.; Hogan, D.; O’Riordan, J.; Salami, B.; Smith, M.; et al. Promoting the Health of Children and Young People Who Migrate: Reflections from Four Regional Reviews. Glob. Health Promot. 2020, 27, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindert, J.; von Ehrenstein, O.S.; Priebe, S.; Mielck, A.; Brähler, E. Depression and Anxiety in Labor Migrants and Refugees—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total Sample | Students’ Immigration Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of Students and Their Family | Non- Immigrant | First- Generation | Second- Generation | p-Value | |

| n | 2151 | 1553 | 110 | 488 | |

| Students’ characteristics | |||||

| Students’ age, years | 8 (3) | 8 (3) | 9 (3) | 8 (3) | 0.085 |

| Boys, % | 51.8 | 51.5 | 50 | 52.5 | 0.892 |

| Student’s highest educational attainment, % | 0.002 | ||||

| Pre-primary school (kindergarten) | 26.5 | 25.0 | 19.4 | 33.0 | |

| Primary school | 65.9 | 66.7 | 73.8 | 61.5 | |

| Secondary school | 7.6 | 8.4 | 6.8 | 5.5 | |

| Family characteristics | |||||

| Parental employment status, % | <0.001 | ||||

| Both parents are employed | 46.0 | 51.7 | 21.8 | 30.7 | |

| One parent is unemployed | 46.1 | 41.3 | 55.1 | 61.3 | |

| Both parents are unemployed | 7.9 | 7.0 | 23.1 | 8.0 | |

| Paternal educational level, % | <0.001 | ||||

| Low | 33.0 | 27.7 | 71.1 | 42.7 | |

| Moderate | 41.3 | 43.3 | 16.7 | 40.0 | |

| High | 25.7 | 29.1 | 12.2 | 17.3 | |

| Maternal educational level, % | <0.001 | ||||

| Low | 25.8 | 19.1 | 66.7 | 39.7 | |

| Moderate | 32.7 | 33.3 | 21.1 | 33.3 | |

| High | 41.4 | 47.6 | 12.2 | 27.0 | |

| Family socioeconomic status, % | |||||

| Low | 30.9 | 25.1 | 62.0 | 43.0 | |

| Moderate | 54.8 | 58.1 | 26.0 | 50.1 | <0.001 |

| High | 14.4 | 16.8 | 12.0 | 6.9 | |

| Households with ≥3 underage members, % | 28.3 | 28.9 | 26.8 | 26.5 | 0.595 |

| Total Sample | Students’ Immigration Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students’ Quality of Life Measurements | Non- Immigrant | First- Generation | Second- Generation | p-Value | |

| n | 2151 | 1553 | 110 | 488 | |

| HRQoL, score (range, 0–100) | 91.3 (81–97.8) | 91.7 (82.6–97.8) | 87.5 (73.8–97.8) * | 89.1 (78.3–96.7) * | <0.001 |

| Poor HRQoL, % | 25.0 | 22.1 | 42.9 | 30.7 | <0.001 |

| Physical function, score (range, 0–100) | 96.9 (84.4–100) | 96.9 (87.5–100) | 90.6 (78.1–100) * | 93.8 (81.3–100) * | <0.001 |

| Poor physical function, % | 25.6 | 23.5 | 34.8 | 30.7 | <0.001 |

| Emotional function, score (range, 0–100) | 90 (75–100) | 90 (75–100) | 87.5 (70–100) | 87.5 (70–100) | 0.463 |

| Poor emotional function, % | 23.0 | 21.9 | 26.1 | 26.1 | 0.163 |

| Social function, score (range, 0–100) | 95 (80–100) | 95 (80–100) | 90 (70–100) | 95 (80–100) | 0.055 |

| Poor social function, % | 22.4 | 21.1 | 32.6 | 24.5 | 0.020 |

| School function, score (range, 0–100) | 90 (80–100) | 95 (80–100) | 87.5 (73.8–97.8) | 90 (75–100) * | <0.001 |

| Poor school function, % | 23.8 | 20.3 | 38.5 | 32.1 | <0.001 |

| Dependent Variable | Poor HRQoL | Poor Physical Function | Poor Emotional Function | Poor Social Function | Poor School Function | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Students’ immigration status | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | Model adjusted for |

| Non-immigrant | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | (Crude model) | |

| First-generation | 2.65 (1.72, 4.09) *** | 1.74 (1.11, 2.72) ** | 1.26 (0.78, 2.04) | 1.81 (1.15, 2.85) ** | 2.45 (1.58, 3.82) *** | ||

| Second-generation | 1.57 (1.23, 2.00) *** | 1.44 (1.13, 1.84) *** | 1.26 (0.98, 1.62) * | 1.21 (0.93, 1.57) | 1.86 (1.45, 2.37) *** | ||

| Model 2 | Students’ immigration status | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

| Non-immigrant | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | Age, sex | |

| First-generation | 2.71 (1.73, 4.24) *** | 1.80 (1.14, 2.84) ** | 1.23 (0.75, 2.02) | 1.86 (1.16, 3) ** | 2.61 (1.64, 4.15) *** | ||

| Second-generation | 1.61 (1.24, 2.10) *** | 1.51 (1.17, 1.96) *** | 1.17 (0.89, 1.54) | 1.23 (0.93, 1.63) | 2.05 (1.57, 2.67) *** | ||

| Model 3 | Students’ immigration status | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

| Non-immigrant | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | Model 2 + family socioeconomic status | |

| First-generation | 2.82 (1.75, 4.53) *** | 1.91 (1.18, 3.10) *** | 1.40 (0.84, 2.36) | 1.94 (1.16, 3.22) ** | 2.52 (1.54, 4.13) *** | ||

| Second-generation | 1.68 (1.28, 2.21) *** | 1.60 (1.23, 2.10) *** | 1.22 (0.92, 1.62) | 1.24 (0.92, 1.67) | 2.09 (1.58, 2.77) *** |

| Dependent Variable | Poor HRQoL | Poor Physical Function | Poor Emotional Function | Poor Social Function | Poor School Function | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Parental country of origin in relation to country of residence (Greece) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | Model adjusted for |

| Same with country of residence (Greece) for both parents | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | (Crude model) | |

| Different from country of residence (Greece) for one parent | 1.65 (1.15, 2.37) *** | 1.34 (0.93, 1.93) | 2.08 (1.46, 2.97) *** | 1.55 (1.07, 2.25) ** | 1.81 (1.25, 2.61) *** | ||

| Different from country of residence (Greece) for both parents | 1.77 (1.37, 2.29) *** | 1.58 (1.22, 2.04) *** | 0.97 (0.73, 1.29) | 1.22 (0.93, 1.61) | 1.99 (1.54, 2.58) *** | ||

| Model 2 | Parental country of origin in relation to country of residence (Greece) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

| Same with country of residence (Greece) for both parents | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | Age, sex | |

| Different from country of residence (Greece) for one parent | 1.76 (1.19, 2.62) *** | 1.46 (0.99, 2.17) * | 1.89 (1.28, 2.78) *** | 1.70 (1.13, 2.56) ** | 2.03 (1.35, 3.04) *** | ||

| Different from country of residence (Greece) for both parents | 1.81 (1.38, 2.37) *** | 1.61 (1.23, 2.1) *** | 0.94 (0.7, 1.27) | 1.24 (0.92, 1.67) | 2.19 (1.66, 2.89) *** | ||

| Model 3 | Parental country of origin in relation to country of residence (Greece) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

| Same with country of residence (Greece) for both parents | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | Model 2 + family socioeconomic status | |

| Different from country of residence (Greece) for one parent | 1.90 (1.27, 2.85) *** | 1.59 (1.06, 2.38) ** | 1.91 (1.28, 2.86) *** | 1.82 (1.2, 2.77) *** | 2.18 (1.44, 3.3) *** | ||

| Different from country of residence (Greece) for both parents | 1.81 (1.36, 2.42) *** | 1.66 (1.25, 2.21) *** | 1.01 (0.73, 1.38) | 1.19 (0.87, 1.64) | 2.18 (1.63, 2.93) *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diamantis, D.V.; Stavropoulou, I.; Katsas, K.; Mugford, L.; Linos, A.; Kouvari, M. Assessing Quality of Life in First- and Second-Generation Immigrant Children and Adolescents; Highlights from the DIATROFI Food Aid and Healthy Nutrition Promotion Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032471

Diamantis DV, Stavropoulou I, Katsas K, Mugford L, Linos A, Kouvari M. Assessing Quality of Life in First- and Second-Generation Immigrant Children and Adolescents; Highlights from the DIATROFI Food Aid and Healthy Nutrition Promotion Program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032471

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiamantis, Dimitrios V., Iliana Stavropoulou, Konstantinos Katsas, Lyndsey Mugford, Athena Linos, and Matina Kouvari. 2023. "Assessing Quality of Life in First- and Second-Generation Immigrant Children and Adolescents; Highlights from the DIATROFI Food Aid and Healthy Nutrition Promotion Program" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032471

APA StyleDiamantis, D. V., Stavropoulou, I., Katsas, K., Mugford, L., Linos, A., & Kouvari, M. (2023). Assessing Quality of Life in First- and Second-Generation Immigrant Children and Adolescents; Highlights from the DIATROFI Food Aid and Healthy Nutrition Promotion Program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032471