The Power of Negative Affect during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Negative Affect Leverages Need Satisfaction to Foster Work Centrality

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Positive and Negative Affectivity and Work Centrality

1.2. The Moderating Role of Basic Needs Satisfaction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Positive and Negative Affectivity

2.2.2. Basic Need Satisfaction

2.2.3. Work Centrality

2.2.4. Control Variables

3. Results

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analyses

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

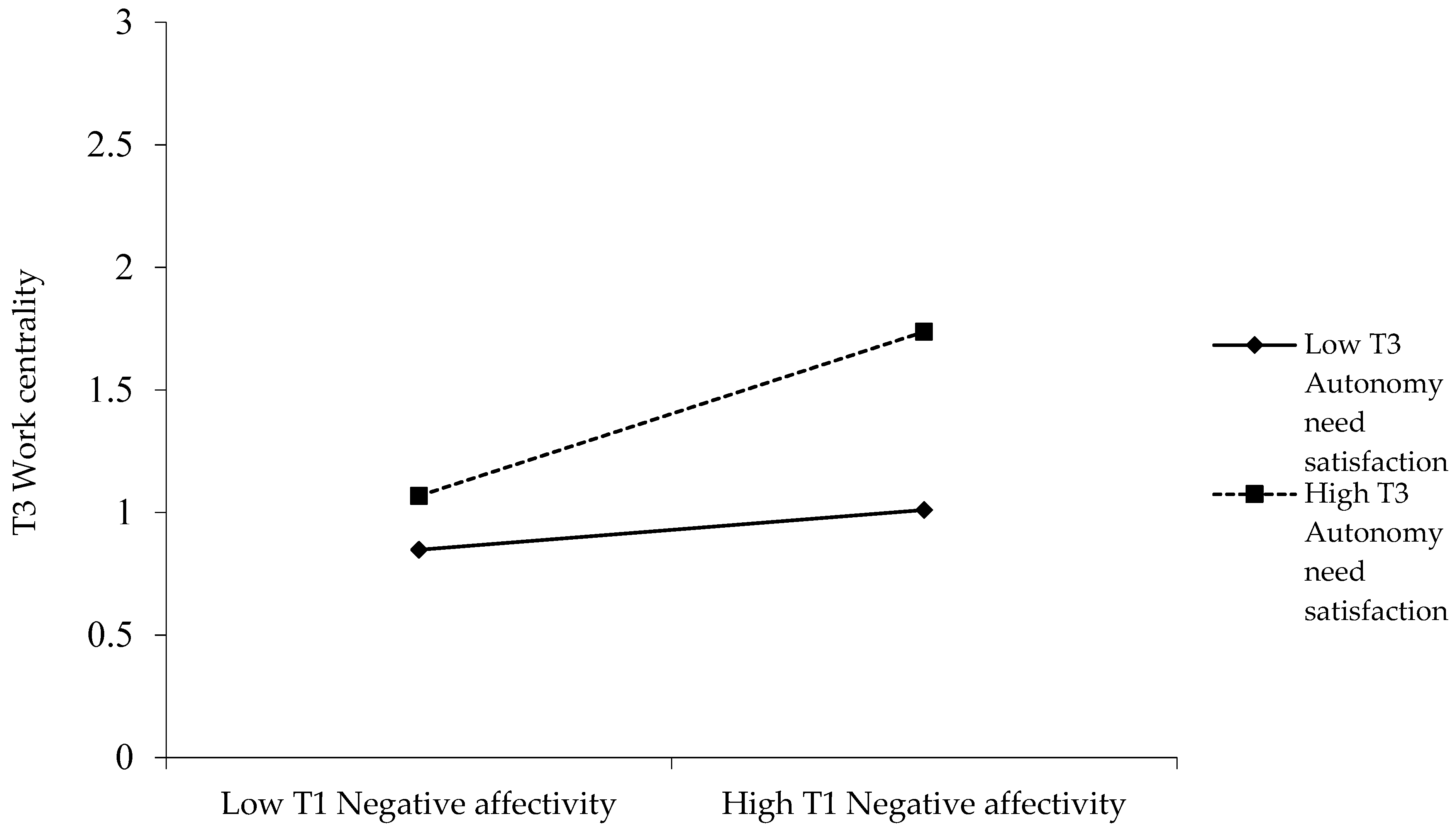

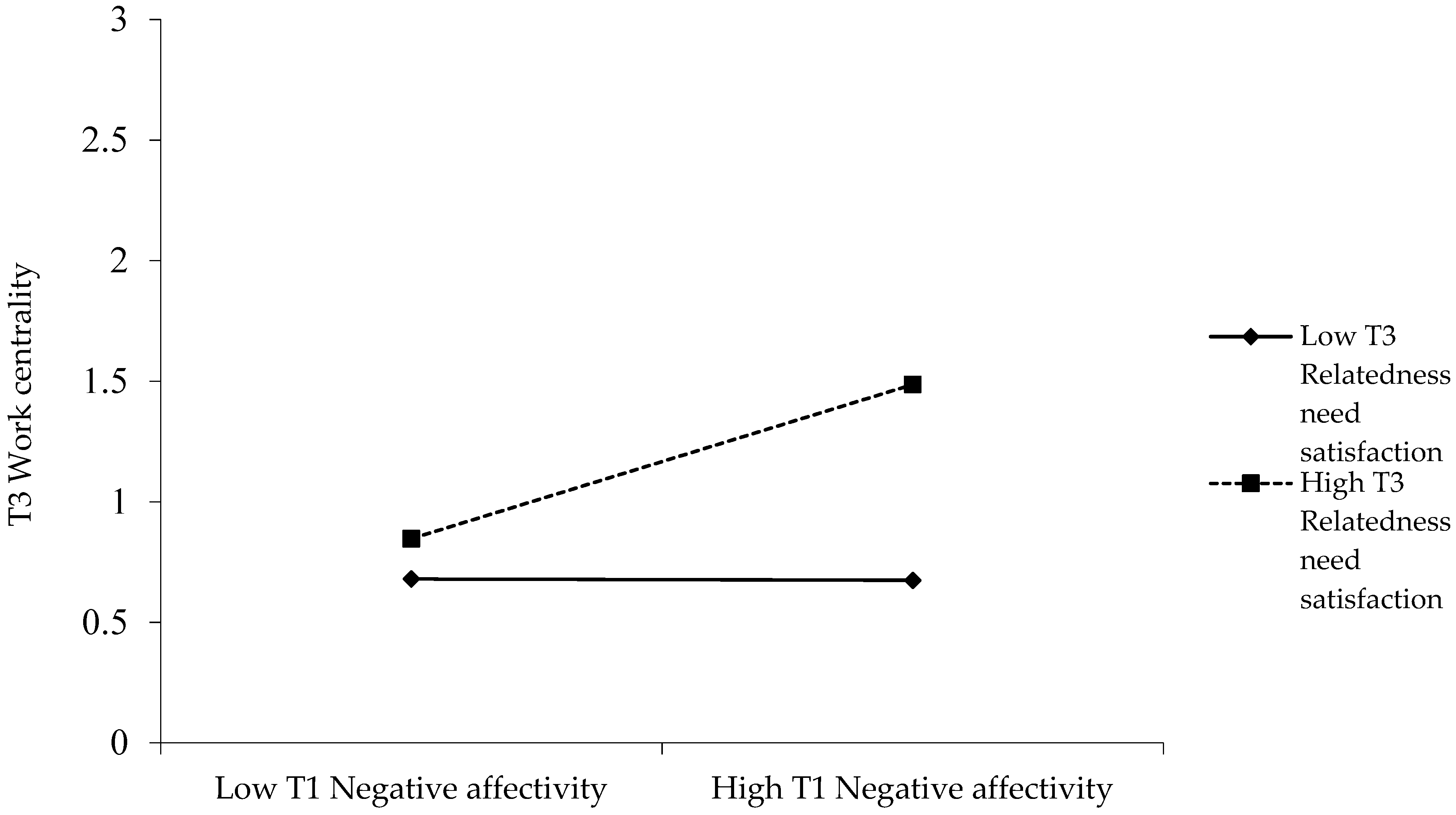

3.3. Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Positive and Negative Affectivity and Work Centrality during the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.2. Basic Needs Satisfaction during the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Probst, T.M.; Lee, H.J.; Bazzoli, A. Economic stressors and the enactment of CDC-recommended COVID-19 prevention behaviors: The impact of state-level context. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1397–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. 2020. Available online: http://data.bls.gov (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Chaney, S.; King, K.U.S. Jobless claims top 30 millions, as spending, personal income drop. Wall Str. J. 2020, A1, A8. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar, N.; Aggarwal, P.; Yeap, J.A.L. Working in lockdown: The relationship between COVID-19 induced work stressors, job performance, distress, and life satisfaction. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 6308–6323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trougakos, J.P.; Chawla, N.; McCarthy, J.M. Working in a pandemic: Exploring the impact of COVID-19 health anxiety on work, family, and health outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kniffin, K.M.; Narayanan, J.; Anseel, F.; Antonakis, J.; Ashford, S.P.; Bakker, A.B.; Bamberger, P.; Bapuji, H.; Bhave, D.P.; Choi, V.K.; et al. COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochazka, J.; Scheel, T.; Pirozek, P.; Kratochvil, T.; Civilotti, C.; Bollo, M.; Maran, D.A. Data on work-related consequences of COVID-19 pandemic for employees across Europe. Data Brief 2020, 32, 106174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, W.J.; Belkin, L.Y.; Tuskey, S.E.; Conroy, S.A. Surviving remotely: How job control and loneliness during a forced shift to remote work impacted employee work behaviors and well-being. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; He, W.; Zhou, K. The mind, the heart, and the leader in times of crisis: How and when COVID-19-triggered mortality salience relates to state anxiety, job engagement, and prosocial behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1218–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalache, M.; Mihalache, O.R. How workplace support for the COVID-19 pandemic and personality traits affect changes in employees’ affective commitment to the organization and job-related well-being. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 61, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Erez, A.; Bono, J.E.; Thoresen, C.J. The Core Self-Evaluations Scale: Development of a measure. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmot, M.P.; Wanberg, C.R.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Ones, D.S. Extraversion advantages at work: A quantitative review and synthesis of the meta-analytic evidence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 1447–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Meng, W.; Xu, M.; Meng, H. Work centrality and recovery experiences in dual-earner couples: Test of an actor-partner interdependence model. Stress Health 2022, 38, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschfeld, R.R.; Feild, H.S. Work centrality and work alienation: Distinct aspects of a general commitment to work. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefendorff, J.M.; Brown, D.J.; Kamin, A.M.; Lord, R.G. Examining the roles of job involvement and work centrality in predicting organizational citizenship behaviors and job performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Johnson, M.J. Meaningful work and affective commitment: A moderated mediation model of positive work reflection and work centrality. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klussman, K.; Nichols, A.L.; Langer, J. Mental health in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal examination of the ameliorating effect of meaning salience. Curr. Psychol. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Wiese, D.; Vaidya, J.; Tellegen, A.E. The two general activation systems of affect: Structural findings, evolutionary considerations, and psychobiological evidence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 820–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Ferris, D.L.; Chang, C.H.; Rosen, C.C. A review of self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1195–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M.; Soenens, B. Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, R.; He, L.; Chang, C.; Wang, M.; Baker, N.; Pan, J.; Jin, Y. Employees’ reactions towards COVID-19 information exposure: Insights from terror management theory and generativity theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 1601–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Sorensen, K.L. Dispositional affectivity and work-related outcomes: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 1255–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoresen, C.J.; Kaplan, S.A.; Barsky, A.P.; Warren, C.R.; de Chermont, K. The affective underpinnings of job perceptions and attitudes: A meta-analytic review and integration. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 914–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radanielina-Hita, M.-L.; Grégoire, Y.; Lussier, B.; Boissonneault, S.; Vandenberghe, C.; Sénécal, S. An extended health belief model for COVID-19: Understanding the media-based processes leading to social distancing and panic buying. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2023, 51, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsky, A.; Thoresen, C.J.; Warren, C.R.; Kaplan, S.A. Modeling negative affectivity and job stress: A contingency-based approach. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 915–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N.A.; Hendricks, E.A.; Wagner, S.H. Positive and negative affectivity and facet satisfaction: A meta-analysis. J. Bus. Psychol. 2008, 23, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S. Approach, avoidance, and the self-regulation of affect and action. Motiv. Emot. 2006, 30, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; White, T.L. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.A. Brain systems that mediate both emotion and cognition. Cogn. Emot. 1990, 4, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Positivity; Crown: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Cohn, M.A.; Coffey, K.A.; Pek, J.; Finkel, S.M. Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenberghe, C.; Panaccio, A.; Bentein, K.; Mignonac, K.; Roussel, P.; Ben Ayed, A.K. Time-based differences in the effects of positive and negative affectivity on perceived supervisor support and organizational commitment among newcomers. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, V.M.; Rivkin, W.; Gerpott, F.H.; Diestel, S.; Kühnel, J.; Prem, R.; Wang, M. Some positivity per day can protect you a long way: A within-person field experiment to test an affect-resource model of employee effectiveness at work. Work Stress 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Positive emotions broaden and build. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Devine, P., Plant, A., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013; Volume 47, pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, N.S. The broaden and build process: Positive affect, ratio of positive to negative affect and general self-efficacy. J. Posit. Psychol. 2014, 9, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Branigan, C. Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cogn. Emot. 2005, 19, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J.; Ganster, D.C.; Fox, M.L. Dispositional affect and work-related stress. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992, 77, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonigan, C.J.; Vasey, M.W. Negative affectivity, effortful control, and attention to threat-relevant stimuli. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2009, 37, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, T.; Lee, C. The role of negative affectivity in pay-at-risk reactions: A longitudinal study. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberghe, C.; Panaccio, A.; Ben Ayed, A.-K. Continuance commitment and turnover: Examining the moderating role of negative affectivity and risk aversion. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanous, J.P.; Poland, T.D.; Premack, S.L.; Davis, K.S. The effects of met expectations on newcomer attitudes and behaviors: A review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992, 77, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Vansteenkiste, M.; De Witte, H.; Soenens, B.; Lens, W. Capturing autonomy, competence, and relatedness at work: Construction and initial validation of the Work-Related Basic Need Satisfaction Scale. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 981–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuvaas, B.; Buch, R.; Weibel, A.; Dysvik, A.; Nerstad, C.G. Do intrinsic and extrinsic motivation relate differently to employee outcomes? J. Econ. Psychol. 2017, 61, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaccio, A.; Vandenberghe, C.; Ben Ayed, A.K. The role of negative affectivity in the relationships between pay satisfaction, affective and continuance commitment, and voluntary turnover: A moderated mediation model. Hum. Relat. 2014, 67, 821–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, J.H.; Burns, D.K.; Sinclair, R.R.; Sliter, M. Amazon Mechanical Turk in organizational psychology: An evaluation and practical recommendations. J. Bus. Psychol. 2017, 32, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSimone, J.A.; Harms, P.D. Dirty data: The effects of screening respondents who provide low-quality data in survey research. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.S.; Blum, T.C. Assessing the non-random sampling effects of subject attrition in longitudinal research. J. Manag. 1996, 22, 627–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.R. Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2007, 38, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiniara, M.; Bentein, K. Linking servant leadership to individual performance: Differentiating the mediating role of autonomy, competence and relatedness need satisfaction. Leadersh. Q. 2016, 27, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, P.M.; Kooij, D. The relations between work centrality, psychological contracts, and job attitudes: The influence of age. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 497–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, M.-T.; Hedayati-Mehdiabadi, A.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X. Development and validation of work ethic instrument to measure Chinese people’s work-related values and attitudes. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2020, 31, 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D.; Du Toit, S.; Du Toit, M. LISREL 8: New Statistical Features; Scientific Software International: Chicago, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, H.; Gottfredson, R.K. Best-practice recommendations for estimating interaction effects using moderated multiple regression. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 776–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, M.A.; Fredrickson, B.L.; Brown, S.L.; Mikels, J.A.; Conway, A.M. Happiness unpacked: Positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion 2009, 9, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Losada, M.F. Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinzing, M.M.; Zhou, J.; West, T.N.; Le Nguyen, K.D.; Wells, J.L.; Fredrickson, B.L. Staying ‘in sync’ with others during COVID-19: Perceived positivity resonance mediates cross-sectional and longitudinal links between trait resilience and mental health. J. Posit. Psychol. 2022, 17, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.-G.; Vandenberghe, C. Is affective commitment always good? A look at within-person effects on needs satisfaction and emotional exhaustion. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 103411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, P.J.; Schutte, N.S. Merging the Self-Determination Theory and the Broaden and Build Theory through the nexus of positive affect: A macro theory of positive functioning. New Ideas Psychol. 2023, 68, 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, L.; Algoe, S.B.; Dutton, J.; Emmons, R.; Fredrickson, B.L.; Heaphy, E.; Moskowitz, J.T.; Neff, K.; Niemiec, R.; Pury, C.; et al. Positive psychology in a pandemic: Buffering, bolstering, and building mental health. J. Posit. Psychol. 2022, 17, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, U.; Jahanzeb, S.; Malik, M.A.R.; Baig, M.U.A. Dispositional causes of burnout, satisfaction, and performance through the fear of COVID-19 during times of pandemic. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| χ2(df) | NNFI | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | Δχ2(Δdf) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Hypothesized seven-factor solution | 734.67*(278) | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.065 | 0.044 | – |

| 2. Six factors: Time 1 positive and negative affectivity combined | 1297.30*(284) | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.110 | 0.091 | 562.63*(6) |

| 3. Six factors: Time 2 and Time 3 work centrality combined | 1054.53*(284) | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.082 | 0.053 | 319.86*(6) |

| 4. Six factors: Time 3 autonomy need satisfaction and Time 3 work centrality combined | 1410.21*(284) | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.097 | 0.091 | 675.54*(6) |

| 5. Six factors: Time 3 relatedness need satisfaction and Time 3 work centrality combined | 1402.57*(284) | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.097 | 0.089 | 667.90*(6) |

| 6. Six factors: Time 3 competence need satisfaction and Time 3 work centrality combined | 1437.37*(284) | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.098 | 0.095 | 702.70*(6) |

| 7. Five factors: Time 3 autonomy, relatedness, and competence need satisfaction combined | 2124.03*(289) | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.150 | 0.079 | 1389.36*(11) |

| 8. One factor: All combined | did not converge | |||||

| Item | Loading |

|---|---|

| Time 1 Positive affectivity | |

| 1. In general, I feel … inspired | 0.70 *** |

| 2. … determined | 0.85 *** |

| 3. … active | 0.76 *** |

| 4. … attentive | 0.75 *** |

| 5. … alert | 0.70 *** |

| Time 1 Negative affectivity | |

| 6. In general, I feel ... upset | 0.70 *** |

| 7. ... nervous | 0.80 *** |

| 8. ... hostile | 0.63 *** |

| 9. ... ashamed | 0.57 *** |

| 10. ... afraid | 0.76 *** |

| Time 2 Work centrality | |

| 11. The major satisfaction in my life came from my job | 0.91 *** |

| 12. The most important things that happened to me involved my work | 0.94 *** |

| Time 3 Autonomy need satisfaction | |

| 13. The degree of freedom I have to do my job the way I think it can be done best | 0.87 *** |

| 14. The opportunities to take personal initiatives in my work | 0.91 *** |

| 15. The level of autonomy I have in my job | 0.92 *** |

| 16. The opportunities to exercise my own judgement and my own action | 0.89 *** |

| Time 3 Relatedness need satisfaction | |

| 17. The positive social interactions I have at work with other people | 0.94 *** |

| 18. The feeling of being part of a group at work | 0.95 *** |

| 19. The close friends I have at work | 0.94 *** |

| 20. The opportunities to talk with people about things that really matter to me | 0.89 *** |

| Time 3 Competence need satisfaction | |

| 21. The feeling of being competent at doing my job | 0.89 *** |

| 22. The level of mastery I can achieve at my task | 0.89 *** |

| 23. The level of confidence about my ability to execute my job properly | 0.79 *** |

| 24. The sense that I can accomplish the most difficult tasks | 0.85 *** |

| Time 3 Work centrality | |

| 25. The major satisfaction in my life came from my job | 0.92 *** |

| 26. The most important things that happened to me involved my work | 0.93 *** |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 48.10 | 11.25 | – | ||||||||||

| 2. Gender | 1.50 | 0.50 | −0.14 ** | – | |||||||||

| 3. Education level | 2.95 | 1.43 | −0.07 | −0.11 ** | – | ||||||||

| 4. Employment status | 1.64 | 0.48 | −0.28 ** | −0.06 | 0.05 | – | |||||||

| 5. Positive affectivity (T1) | 5.09 | 0.89 | 0.21 ** | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | (0.86) | ||||||

| 6. Negative affectivity (T1) | 3.05 | 0.97 | −0.13 ** | 0.08 * | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.26 ** | (0.82) | |||||

| 7. Work centrality (T2) | 3.59 | 1.47 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.10 * | 0.12 ** | 0.08 | (0.93) | ||||

| 8. Autonomy need satis. (T3) | 5.23 | 1.35 | 0.15 ** | −0.10 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.28 * | −0.24 ** | 0.19 ** | (0.94) | |||

| 9. Relatedness need satis. (T3) | 4.80 | 1.36 | 0.11 * | −0.12 * | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.24 ** | −0.11 * | 0.18 ** | 0.53 ** | (0.92) | ||

| 10. Compet. need satis. (T3) | 5.45 | 1.29 | 0.18 ** | −0.11 * | −0.00 | 0.07 | 0.30 ** | −0.26 ** | 0.13 * | 0.72 ** | 0.58 ** | (0.96) | |

| 11. Work centrality (T3) | 3.67 | 1.43 | 0.13 * | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.19 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.17 ** | (0.92) |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step | Variable(s) Entered | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 |

| 1 | Age (T1) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |||

| Gender (T1) | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | ||||

| Education level (T1) | 0.08 * | 0.08 * | 0.08 * | ||||

| Employment status (T1) | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.06 | ||||

| Work centrality (T2) | 0.64 *** | 0.64 *** | 0.64 *** | ||||

| 0.43 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.43 *** | |||||

| 2 | Positive affectivity (T1) | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | |||

| Negative affectivity (T1) | 0.10 * | 0.10 * | 0.10 * | ||||

| 0.01 * | 0.01 * | 0.01 * | |||||

| 3 | Autonomy need satisfaction (T3) | 0.17 *** | |||||

| 0.02 *** | |||||||

| Relatedness need satisfaction (T3) | 0.16 *** | ||||||

| 0.02 *** | |||||||

| Competence need satisfaction (T3) | 0.13 ** | ||||||

| 0.01 ** | |||||||

| 4 | Positive affectivity × Autonomy need satis. | 0.02 | |||||

| Negative affectivity × Autonomy need satis. | 0.10 * | ||||||

| 0.01 † | |||||||

| Positive affectivity × Relatedness need satis. | 0.02 | ||||||

| Negative affectivity × Relatedness need satis. | 0.13 ** | ||||||

| 0.01 ** | |||||||

| Positive affectivity × Competence need satis. | 0.04 | ||||||

| Negative affectivity × Competence need satis. | 0.07 | ||||||

| 0.00 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toutant, J.; Vandenberghe, C. The Power of Negative Affect during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Negative Affect Leverages Need Satisfaction to Foster Work Centrality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032379

Toutant J, Vandenberghe C. The Power of Negative Affect during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Negative Affect Leverages Need Satisfaction to Foster Work Centrality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):2379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032379

Chicago/Turabian StyleToutant, Jérémy, and Christian Vandenberghe. 2023. "The Power of Negative Affect during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Negative Affect Leverages Need Satisfaction to Foster Work Centrality" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 2379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032379

APA StyleToutant, J., & Vandenberghe, C. (2023). The Power of Negative Affect during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Negative Affect Leverages Need Satisfaction to Foster Work Centrality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032379